Historic Sites on Chequamegon Bay

July 25, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Historical Sites on Chequamegon Bay was originally published in Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: Volume XIII, by Reuben Gold Thwaites, 1895, pages 426-440.

HISTORIC SITES ON CHEQUAMEGON BAY.1

—

BY CHRYSOSTOM VERWYST, O.S.F.

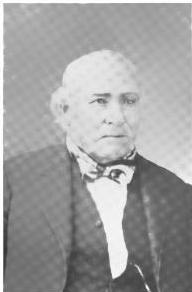

Reverend Chrysostome Verwyst, circa 1918.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

One of the earliest spots in the Northwest trodden by the feet of white men was the shore of Chequamegon Bay. Chequamegon is a corrupt form of Jagawamikong;2 or, as it was written by Father Allouez in the Jesuit Relation for 1667, Chagaouamigong. The Chippewas on Lake Superior have always applied this name exclusively to Chequamegon Point, the long point of land at the entrance of Ashland Bay. It is now commonly called by whites, Long Island; of late years, the prevailing northeast winds have caused Lake Superior to make a break through this long, narrow peninsula, at its junction with the mainland, or south shore, so that it is in reality an island. On the northwestern extremity of this attenuated strip of land, stands the government light-house, marking the entrance of the bay.

William Whipple Warren, circa 1851.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

W. W. Warren, in his History of the Ojibway Nation3, relates an Indian legend to explain the origin of this name. Menabosho, the great Algonkin demi-god, who made this earth anew after the deluge, was once hunting for the great beaver in Lake Superior, which was then but a large beaver-pond. In order to escape his powerful enemy, the great beaver took refuge in Ashland Bay. To capture him, Menabosho built a large dam extending from the south shore of Lake Superior across to Madelaine (or La Pointe) Island. In doing so, he took up the mud from the bottom of the bay and occasionally would throw a fist-full into the lake, each handful forming an island, – hence the origin of the Apostle Islands. Thus did the ancient Indians, the “Gété-anishinabeg,” explain the origin of Chequamegon Point and the islands in the vicinity. His dam completed, Menabosho started in pursuit of the patriarch of all the beavers ; he thinks he has him cornered. But, alas, poor Menabosho is doomed to disappointment. The beaver breaks through the soft dam and escapes into Lake Superior. Thence the word chagaouamig, or shagawamik (“soft beaver-dam”), – in the locative case, shagawamikong (“at the soft beaver-dam”).

Reverend Edward Jacker

~ FindAGrave.com

Rev. Edward Jacker, a well-known Indian scholar, now deceased, suggests the following explanation of Chequamegon: The point in question was probably first named Jagawamika (pr. shagawamika), meaning “there are long, far-extending breakers;” the participle of this verb is jaiagawamikag (“where there are long breakers”). But later, the legend of the beaver hunt being applied to the spot, the people imagined the word amik (a beaver) to be a constituent part of the compound, and changed the ending in accordance with the rules of their language, – dropping the final a in jagawamika, making it jagawamik, – and used the locative case, ong (jagawamikong), instead of the participial form, ag (jaiagawamikag).4

The Jesuit Relations apply the Indian name to both the bay and the projection of land between Ashland Bay and Lake Superior. our Indians, however, apply it exclusively to this point at the entrance of Ashland Bay. It was formerly nearly connected with Madelaine (La Pointe) Island, so that old Indians claim a man might in early days shoot with a bow across the intervening channel. At present, the opening is about two miles wide. The shores of Chequamegon Bay have from time immemorial been the dwelling-place of numerous Indian tribes. The fishery was excellent in the bay and along the adjacent islands. The bay was convenient to some of the best hunting grounds of Northern Wisconsin and Minnesota. The present writer was informed, a few years ago, that in Douglas county alone 2,500 deer had been killed during one short hunting season.5 How abundant must have been the chase in olden times, before the white had introduced to this wilderness his far-reaching fire-arms! Along the shores of our bay were established at an early day fur-trading posts, where adventurous Frenchmen carried on a lucrative trade with their red brethren of the forest, being protected by French garrisons quartered in the French fort on Madelaine Island.

From Rev. Henry Blatchford, an octogenarian, and John B. Denomie (Denominé), an intelligent half-breed Indian of Odanah, near Ashland, the writer has obtained considerable information as to the location of ancient and modern aboriginal villages on the shores of Chequamegon Bay. Following are the Chippewa names of the rivers and creeks emptying into the bay, where there used formerly to be Indian villages:

Charles Whittlesey documented several pictographs along the Bad River.

Mashki-Sibi (Swamp River, misnamed Bad River): Up this river are pictured rocks, now mostly covered with earth, on which in former times Indians engraved in the soft stone the images of their dreams, or the likenesses of their tutelary manitous. Along this river are many maple-groves, where from time immemorial they have made maple-sugar.

Makodassonagani-Sibi (Bear-trap River), which emptties into the Kakagon. The latter seems in olden times to have been the regular channel of Bad River, when the Bad emptied into Ashland Bay, instead of Lake Superior, as it now does. Near the mouth of the Kakagon are large wild-rice fields, where the Chippewas annually gather, as no doubt did their ancestors, great quantities of wild rice (Manomin). By the way, wild rice is very palatable, and the writer and his dusky spiritual children prefer it to the rice of commerce, although it does not look quite so nice.

Bishigokwe-Sibiwishen is a small creek, about six miles or so east of Ashland. Bishigokwe means a woman who has been abandoned by her husband. In olden times, a French trader resided at the mouth of this creek. He suddenly disappeared, – whether murdered or not, is not known. His wife continued to reside for many years at their old home, hence the name.

Nedobikag-Sibiwishen is the Indian name for Bay City Creek, within the limits of Ashland. Here Tagwagané, a celebrated Indian chief of the Crane totem, used occasionally to reside. Warren6 gives us a speech of his, at the treaty of La Pointe in 1842. This Tagwagané had a copper plate, an heirloom handed down in his family from generation to generation, on which were rude indentations and hieroglyphics denoting the number of generations of that family which had passed away since they first pitched their lodges at Shagawamikong and took possession of the adjacent country, including Madelaine Island. From this original mode of reckoning time, Warren concludes that the ancestors of said family first came to La Pointe circa A. D. 1490.

Detail of “Ici était une bourgade considerable” from Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin, 1744.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Metabikitigweiag-Sibiwishen is the creek between Ashland and Ashland Junction, which runs into Fish Creek a short distance west of Ashland. At the junction of these two creeks and along their banks, especially on the east bank of Fish Creek, was once a large and populous Indian village of Ottawas, who there raised Indian corn. It is pointed out on N. Bellin’s map (1744)7, with the remark, Ici était une bourgade considerable (“here was once a considerable village”). We shall hereafter have occasion to speak of this place. The soil along Fish Creek is rich, formed by the annual overflowage of its water, leaving behind a deposit of rich, sand loam. There a young growth of timber along the right bank between the bay and Ashland Junction, and the grass growing underneath the trees shows that it was once a cultivated clearing. It was from this place that the trail left the bay, leading to the Chippewa River country. Fish Creek is called by the Indians Wikwedo-Sibiwishen, which means “Bay Creek,” from wikwed, Chippewa for bay; hence the name Wikwedong, the name they gave to Ashland, meaning “at the bay.”

Whittlesey Creek (National Wildlife Refuge) was named after Asaph Whittlesey, brother of Charles Whittlesey. Photo of Asaph, circa 1860.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

According to Blatchford, there was formerly another considerable village at the mouth of Whittlesey’s Creek, called by the Indians Agami-Wikwedo-Sibiwishen, which signifies “a creek on the other side of the bay,” from agaming (on the other side of a river, or lake), wikwed (a bay), and sibiwishen (a creek). I think that Fathers Allouez and Marquette had their ordinary abode at or near this place, although Allouez seems also to have resided for some time at the Ottawa village up Fish Creek.

A short distance from Whittlesey’s Creek, at the western bend of the bay, where is now Shore’s Landing, there used to be a large Indian village and trading-post, kept by a Frenchman. Being at the head of the bay, it was the starting point of the Indian trail to the St. Croix country. Some years ago the writer dug up there, an Indian mound. The young growth of timber at the bend of the bay, and the absence of stumps, indicate that it had once been cleared. At the foot of the bluff or bank, is a beautiful spring of fresh water. As the St. Croix country was one of the principal hunting grounds of the Chippewas and Sioux, it is natural there should always be many living at the terminus of the trail, where it struck the bay.

From this place northward, there were Indian hamlets strung along the western shore of the bay. Father Allouez mentions visiting various hamlets two, three, or more (French) leagues away from his chapel. Marquette mentions five clearings, where Indian villages were located. At Wyman’s place, the writer some years ago dug up two Indian mounds, one of which was located on the very bank of the bay and was covered with a large number of boulders, taken from the bed of the bay. In this mound were found a piece of milled copper, some old-fashioned hand-made iron nails, the stem of a clay pipe, etc. The objects were no doubt relics of white men, although Indians had built the mound itself, which seemed like a fire-place shoveled under, and covered with large boulders to prevent it from being desecrated.

Boyd’s Creek is called in Chippewa, Namebinikanensi-Sibiwishen, meaning “Little Sucker Creek.” A man named Boyd once resided there, married to an Indian woman. He was shot in a quarrel with another man. One of his sons resides at Spider Lake, and another at Flambeau Farm, while two of his grand-daughters live at Lac du Flambeau.

Further north is Kitchi-Namebinikani-Sibiwishen, meaning “Large Sucker Creek,” but whites now call it Bonos Creek. These two creeks are not far apart, and once there was a village of Indians there. It was noted as a place for fishing at a certain season of the year, probably in spring, when suckers and other fish would go up these creeks to spawn.

At Vanderventer’s Creek, near Washburn, was the celebrated Gigito-Mikana, or “council-trail,” so called because here the Chippewas once held a celebrated council; hence the Indian name Gigito-Mikana-Sibiwishen, meaning “Council-trail Creek.” At the mouth of this creek, there was once a large Indian village.

There used also to be a considerable village between Pike’s Bay and Bayfield. It was probably there that the celebrated war chief, Waboujig, resided.

John Baptiste Denomie

~ Noble Lives of a Noble Race, A Series of Reproductions by the Pupils of Saint Mary’s, Odanah, Wisconsin, page 213-217.

There was once an Indian village where Bayfield now stands, also at Wikweiag (Buffalo Bay), at Passabikang, Red Cliff, and on Madelaine Island. The writer was informed by John B. Denomie, who was born on the island in 1834, that towards Chabomnicon Bay (meaning “Gooseberry Bay”) could long ago be seen small mounds or corn-hills, now overgrown with large trees, indications of early Indian agriculture. There must have been a village there in olden times. Another ancient village was located on the southwestern extremity of Madelaine Island, facing Chequamegon Point, where some of their graves may still be seen. It is also highly probable that there were Indian hamlets scattered along the shore between Bayfield and Red Cliff, the most northern mainland of Wisconsin. There is now a large, flourishing Indian settlement there, forming the Red Cliff Chippewa reservation. There is a combination church and school there at present, under the charge of the Franciscan Order. Many Indians also used to live on Chequamegon Point, during a great part of the year, as the fishing was good there, and blueberries were abundant in their season. No doubt from time immemorial Indians were wont to gather wild rice at the mouth of the Kakagon, and to make maple sugar up Bad River.

Illustration from The Story of Chequamegon Bay, Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: Volume XIII, 1895, page 419.

We thus see that the Jesuit Relations are correct when they speak of many large and small Indian villages (Fr. bourgades) along the shores of Chequamegon Bay. Father Allouez mentions two large Indian villages at the head of the bay – the one an Ottawa village, on Fish Creek; the other a Huron, probably between Shore’s Landing and Washburn. Besides, he mentions smaller hamlets visited by him on his sick-calls. Marquette says that the Indians lived there in five clearings, or villages. From all this we see that the bay was from most ancient times the seat of a large aboriginal population. Its geographical position towards the western end of the great lake, its rich fisheries and hunting grounds, all tended to make it the home of thousands of Indians. Hence it is much spoken of by Perrot, in his Mémoire, and by most writers on the Northwest of the last century. Chequamegon Bay, Ontonagon, Keweenaw Bay, and Sault Ste. Marie (Baweting) were the principal resorts of the Chippewa Indians and their allies, on the south shore of Lake Superior.

“Front view of the Radisson cabin, the first house built by a white man in Wisconsin. It was built between 1650 and 1660 on Chequamegon Bay, in the vicinity of Ashland. This drawing is not necessarily historically accurate.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

The first white men on the shores of Chequamegon Bay were in all probability Groseilliers and Radisson. They built a fort on Houghton Point, and another at the head of the bay, somewhere between Whittlesey’s Creek and Shore’s Landing, as in some later paper I hope to show from Radisson’s narrative.8 As to the place where he shot the bustards, a creek which led him to a meadow9, I think this was Fish Creek, at the mouth of which is a large meadow, or swamp.10

After spending six weeks in the Sioux country, our explorers retraced their steps to Chequamegon Bay, arriving there towards the end of winter. They built a fort on Houghton Point. The Ottawas had built another fort somewhere on Chequamegon Point. In travelling towards this Ottawa fort, on the half-rotten ice, Radisson gave out and was very sick for eight days; but by rubbing his legs with hot bear’s oil, and keeping them well bandaged, he finally recovered. After his convalescence, our explorers traveled northward, finally reaching James Bay.

The next white men to visit our bay were two Frenchmen, of whom W. W. Warren says:11

“One clear morning in the early part of winter, soon after the islands which are clustered in this portion of Lake Superior, and known as the Apostles, had been locked in ice, a party of young men of the Ojibways started out from their village in the Bay of Shag-a-waum-ik-ong [Chequamegon], to go, as was customary, and spear fish through holes in the ice, between the island of La Pointe and the main shore, this being considered as the best ground for this mode of fishing. While engaged in this sport, they discovered a smoke arising from a point of the adjacent island, toward its eastern extremity.

“The island of La Pointe was then totally unfrequented, from superstitious fears which had but a short time previous led to its total evacuation by the tribe, and it was considered an act of the greatest hardihood for any one to set foot on its shores. The young men returned home at evening and reported the smoke which they had seen arising from the island, and various were the conjectures of the old people respecting the persons who would dare to build a fire on the spirit-haunted isle. They must be strangers, and the young men were directed, should they again see the smoke, to go and find out who made it.

“Early the next morning, again proceeding to their fishing-ground, the young men once more noticed the smoke arising from the eastern end of the unfrequented island, and, again led on by curiosity, they ran thither and found a small log cabin, in which they discovered two white men in the last stages of starvation. The young Ojibways, filled with compassion, carefully conveyed them to their village, where being nourished with great kindness, their lives were preserved.

“These two white men had started from Quebec during the summer with a supply of goods, to go and find the Ojibways who every year had brought rich packs of beaver to the sea-coast, notwithstanding that their road was barred by numerous parties of the watchful and jealous Iroquois. Coasting slowly up the southern shores of the Great Lake late in the fall, they had been driven by the ice on to the unfrequented island, and not discovering the vicinity of the Indian village, they had been for some time enduring the pangs of hunger. At the time they were found by the young Indians, they had been reduced to the extremity of roasting and eating their woolen cloth and blankets as the last means of sustaining life.

“Having come provided with goods they remained in the village during the winter, exchanging their commodities for beaver skins. They ensuing spring a large number of the Ojibways accompanied them on their return home.

“From close inquiry, and judging from events which are said to have occurred about this period of time, I am disposed to believe that this first visit by the whites took place about two hundred years ago [Warren wrote in 1852]. It is, at any rate, certain that it happened a few years prior to the visit of the ‘Black-gowns’ [Jesuits] mentioned in Bancroft’s History, and it is one hundred and eighty-four years since this well-authenticated occurrence.”

So far Warren; he is, however, mistaken as to the date of the first black-gown’s visit, which was not 1668 but 1665.

Portrayal of Claude Allouez

~ National Park Service

The next visitors to Chequamegon Bay were Père Claude Allouez and his six companions in 1665. We come now to a most interesting chapter in the history of our bay, the first formal preaching of the Christian religion on its shores. For a full account of Father Allouez’s labors here, the reader is referred to the writer’s Missionary Labors of Fathers Marquette, Allouez, and Ménard in the Lake Superior Region. Here will be given merely a succinct account of their work on the shores of the bay. To the writer it has always been a soul-inspiring thought that he is allowed to tread in the footsteps of those saintly men, who walked, over two hundred years ago, the same ground on which he now travels; and to labor among the same race for which they, in starvation and hardship, suffered so much.

In the Jesuit Relation for 1667, Father Allouez thus begins the account of his five years’ labors on the shores of our bay:

“On the eight of August of the year 1665, I embarked at Three Rivers with six Frenchmen, in company with more than four hundred Indians of different tribes, who were returning to their country, having concluded the little traffic for which they had come.”

Marquis Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy

~ Wikipedia.org

His voyage into the Northwest was one of the great hardships and privations. The Indians willingly took along his French lay companions, but him they disliked. Although M. Tracy, the governor of Quebec, had made Father Allouez his ambassador to the Upper Algonquins, thus to facilitate his reception in their country, nevertheless they opposed him accompanying them, and threatened to abandon him on some desolate island. No doubt the medicine-men were the principal instigators of this opposition. He was usually obliged to paddle like the rest, often till late in the night, and that frequently without anything to eat all day.

“On a certain morning,” he says, “a deer was found, dead since four or five days. It was a lucky acquisition for poor famished beings. I was offered some, and although the bad smell hindered some from eating it, hunger made me take my share. But I had in consequence an offensive odor in my mouth until the next day. In addition to all these miseries we met with, at the rapids I used to carry packs as large as possible for my strength; but I often succumbed, and this gave our Indians occasion to laugh at me. They used to make fun of me, saying a child ought to be called to carry me and my baggage.”

August 24, they arrived at Lake Huron, where they made a short stay; then coasting along the shores of that lake, they arrived at Sault Ste. Marie towards the beginning of September. September 2, they entered Lake Superior, which the Father named Lake Tracy in acknowledgement of the obligations which the people of those upper countries owed to the governor. Speaking of his voyage on Lake Superior, Father Allouez remarks:

“Having entered Lake Tracy, we were engaged the whole month of September in coasting along the south shore. I had the consolation of saying holy mass, as I now found myself alone with our Frenchmen, which I had not been able to do since my departure from Three Rivers. * * * We afterwards passed the bay, called by the aged, venerable Father Ménard, Sait Theresa [Keweenaw] Bay.”

Speaking of his arrival at Chequamegon Bay, he says:

“After having traveled a hundred and eighty leagues on the south shore of Lake Tracy, during which our Saviour often deigned to try our patience by storms, hunger, daily and nightly fatigues, we finally, on the first day of October, 1665, arrived at Chagaouamigong, for which place we had sighed so long. It is a beautiful bay, at the head of which is situated the large village of the Indians, who there cultivate fields of Indian corn and do not lead a nomadic life. There are at this place men bearing arms, who number about eight hundred; but these are gathered together from seven different tribes, and live in peacable community. This great number of people induced us to prefer this place to all others for our ordinary abode, in order to attend more conveniently to the instruction of these heathens, to put up a chapel there and commence the functions of Christianity.”

Further on, speaking of the site of his mission and its chapel, he remarks:

“The section of the lake shore, where we have settled down, is between two large villages, and is, as it were, the center of all the tribes of these countries, because the fishing here is very good, which is the principal source of support of these people.”

To locate still more precisely the exact site of his chapel, he remarks, speaking of the three Ottawa clans (Outaouacs, Kiskakoumacs, and Outaoua-Sinagonc):

“I join these tribes [that is, speaks of them as one tribe] because they had one and the same language, which is the Algonquin, and compose one of the same village, which is opposite that of the Tionnontatcheronons [Hurons of the Petun tribe] between which villages we reside.”

But where was that Ottawa village? A casual remark of Allouez, when speaking of the copper mines of Lake Superior, will help us locate it.

“It is true,” says he, “on the mainland, at the place where the Outaouacs raise Indian corn, about half a league from the edge of the water, the women have sometimes found pieces of copper scattered here and there, weighing ten, twenty or thirty pounds. It is when digging into the sand to conceal their corn that they make these discoveries.”

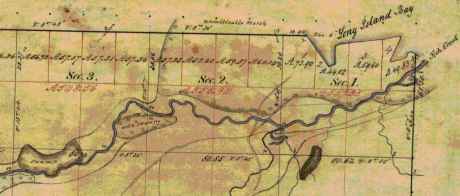

Detail of Fish Creek from Township 47 North Range 5 West.

~ Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records

Allouez evidently means Fish Creek. About a mile or so from the shore of the bay, going up this creek, can be seen traces of an ancient clearing on the left-hand side, where Metabikitigweiag Creeek empties into Fish Creek, about half-way between Ashland and Ashland Junction. The writer examined the locality about ten years ago. This then is the place where the Ottawas raised Indian corn and had their village. In Charlevoix’s History of New France, the same place is marked as the site of an ancient large village. The Ottawa village on Fish Creek appears to have been the larger of the two at the head of Chequamegon Bay, and it was there Allouez resided for a time, until he was obliged to return to his ordinary dwelling place, “three-fourths of a league distant.” This shows that the ordinary abode of Father Allouez and Marquette, the site of their chapel, was somewhere near Whittlesey’s Creek or Shore’s Landing. The Huron village was most probably along the western shore of the bay, between Shore’s Landing and Washburn.

Detail of Ashland next to an ancient large village (unmarked) in Township 47 North Range 4 West.

~ Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records

Father Allouez did not confine his apostolic labors to the two large village at the head of the bay. He traveled all over the neighborhood, visiting the various shore hamlets, and he also spent a month at the western extremity of Lake Superior – probably at Fond du Lac – where he met with some Chippewas and Sioux. In 1667 he crossed the lake, most probably from Sand Island, in a frail birch canoe, and visited some Nipissirinien Christians at Lake Nepigon (Allimibigong). The same year he went to Quebec with an Indian flotilla, and arrived there on the 3d of August, 1667. After only two days’ rest he returned with the same flotilla to his far distant mission on Chequamegon Bay, taking along Father Louis Nicholas. Allouez contained his missionary labors here until 1669, when he left to found St. Francis Xavier mission at the head of Green Bay. His successor at Chequamegon Bay was Father James Marquette, discoverer and explorer of the Mississippi. Marquette arrived here September 13, 1669, and labored until the spring of 1671, when he was obliged to leave on account of the war which had broken out the year before, between the Algonquin Indians at Chequamegon Bay and their western neighbors, the Sioux.

1 – See ante, p. 419 for map of the bay. – ED.

2 – In writing Indian names, I follow Baraga’s system of orthography, giving the French quality to both consonants and vowels.

3 – Minn. Hist. Colls., v. – ED.

4 – See ante, p. 399, note. – ED.

5 – See Carr’s interesting and exhaustive article, “The Food of Certain American Indians,” in Amer. Antiq. Proc., x., pp. 155 et seq. – ED.

6 – Minn. Hist. Colls., v. – ED.

7 – In Charlevoix’s Nouvelle France. – ED.

8 – See Radisson’s Journal, in Wis. Hist. Colls., xi. Radisson and Groseilliers reached Chequamegon Bay late in the autumn of 1661. – ED.

9 – Ibid., p. 73: “I went to the wood some 3 or 4 miles. I find a small brooke, where I walked by ye sid awhile, wch brought me into meddowes. There was a poole, where weare a good store of bustards.” – ED.

10 – Ex-Lieut. Gov. Sam. S. Fifield, of Ashland, writes me as follows:

“After re-reading Radisson’s voyage to Bay Chewamegon, I am satisfied that it would by his description be impossible to locate the exact spot of his camp. The stream in which he found the “pools,” and where he shot fowl, is no doubt Fish Creek, emptying into the bay at its western extremity. Radisson’s fort must have been near the head of the bay, on the west shore, probably at or near Boyd’s Creek, as there is an outcropping of rock in that vicinity, and the banks are somewhat higher than at the head of the bay, where the bottom lands are low and swampy, forming excellent “duck ground” even to this day. Fish Creek has three outlets into the bay, – one on the east shore or near the east side, one central, and one near the western shore; for full two miles up the stream, it is a vast swamp, through which the stream flows in deep, sluggish lagoons. Here, in the early days of American settlement, large brook trout were plenty; and even in my day many fine specimens have been taken from these “pools.” Originally, there was along these bottoms a heavy elm forest, mixed with cedar and black ash, but it has now mostly disappeared. An old “second growth,” along the east side, near Prentice Park, was evidently once the site of an Indian settlement, probably of the 18th century.

“I am of the opinion that the location of Allouez’s mission was at the mouth of Vanderventer’s Creek, on the west shore of the bay, near the present village of Washburn. It was undoubtedly once the site of a large Indian village, as was the western part of the present city of Ashland. When I came to this locality, nearly a quarter of a century ago, “second growth” spots could be seen in several places, where it was evident that the Indians had once had clearings for their homes. The march of civilization has obliterated these landmarks of the fur-trading days, when the old French voyageurs made the forest-clad shores of our beautiful bay echo with their boat songs, and when resting from their labors sparked the dusky maidens in their wigwams.”

Rev. E. P. Wheeler, of Ashland, a native of Madelaine Island, and an authority on the region, writes me:

“I think Radisson’s fort was at the mouth of Boyd’s Creek, – at least that place seems for the present to fulfill the conditions of his account. it is about three or four miles from here to Fish Creek valley, which leads, when followed down stream, to marshes ‘meadows, and a pool.’ No other stream seems to have the combination as described. Boyd’s Creek is about four miles from the route he probably took, which would be by way of the plateau back from the first level, near the lake. Radisson evidently followed Fish Creek down towards the lake, before reaching the marshes. This condition is met by the formation of the creek, as it is some distance from the plateau through which Fish Creek flows to its marshy expanse. Only one thing makes me hesitate about coming to a final decision, – that is, the question of the age of the lowlands and formations around Whittlesey Creek. I am going to go over the ground with an expert geologist, and will report later. Thus far, there seems to be no reason to doubt that Fish Creek is the one upon which Radisson hunted.” – ED.

11 – Minn. Hist. Colls., v., pp. 121, 122, gives the date as 1652. – ED.

The Enemy of my Enemy: The 1855 Blackbird-Wheeler Alliance

November 29, 2013

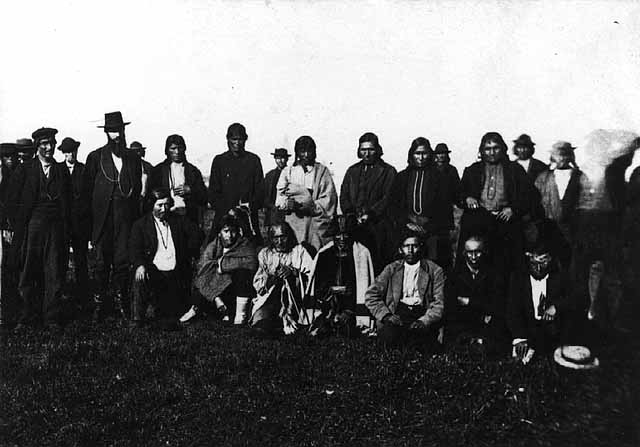

Identified by the Minnesota Historical Society as “Scene at Indian payment, probably at Odanah, Wisconsin. c. 1865.” by Charles Zimmerman. Judging by the faces in the crowd, this is almost certainly the same payment as the more-famous image that decorates the margins of the Chequamegon History site (Zimmerman MNHS Collections)

A staunch defender of Ojibwe sovereignty, and a zealous missionary dedicating his life’s work to the absolute destruction of the traditional Ojibwe way of life, may not seem like natural political allies, but as Shakespeare once wrote, “Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows.”

In October of 1855, two men who lived near Odanah, were miserable and looking for help. One was Rev. Leonard Wheeler who had founded the Protestant mission at Bad River ten years earlier. The other was Blackbird, chief of the “Bad River” faction of the La Pointe Ojibwe, that had largely deserted La Pointe in the 1830s and ’40s to get away from the men like Wheeler who pestered them relentlessly to abandon both their religion and their culture.

Their troubles came in the aftermath of the visit to La Pointe by George Manypenny, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to oversee the 1855 annuity payments. Many readers may be familiar with these events, if they’ve read Richard Morse’s account, Chief Buffalo’s obituary (Buffalo died that September while Manypenny was still on the island), or the eyewitness account by Crockett McElroy that I posted last month. Taking these sources together, some common themes emerge about the state of this area in 1855:

- After 200 years, the Ojibwe-European relationship based on give and take, where the Ojibwe negotiated from a position of power and sovereignty, was gone. American government and society had reached the point where it could by impose its will on the native peoples of Lake Superior. Most of the land was gone and with it the resource base that maintained the traditional lifestyle, Chief Buffalo was dead, and future chiefs would struggle to lead under the paternalistic thumb of the Indian Department.

- With the creation of the reservations, the Catholic and Protestant missionaries saw an opportunity, after decades of failures, to make Ojibwe hunters into Christian farmers.

- The Ojibwe leadership was divided on the question of how to best survive as a people and keep their remaining lands. Some chiefs favored rapid assimilation into American culture while a larger number sought to maintain traditional ways as best as possible.

- The mix-blooded Ojibwe, who for centuries had maintained a unique identity that was neither Native nor European, were now being classified as Indians and losing status in the white-supremacist American culture of the times. And while the mix-bloods maintained certain privileges denied to their full-blooded relatives, their traditional voyageur economy was gone and they saw treaty payments as one of their only opportunities to make money.

- As with the Treaties of 1837 and 1842, and the tragic events surrounding the attempted removals of 1850 and 1851, there was a great deal of corruption and fraud associated with the 1855 payments.

This created a volatile situation with Blackbird and Wheeler in the middle. Before, we go further, though, let’s review a little background on these men.

This 1851 reprint from Lake Superior Journal of Sault Ste. Marie shows how strongly Blackbird resisted the Sandy Lake removal efforts and how he was a cultural leader as well as a political leader. (New Albany Daily Ledger, October 9, 1851. Pg. 2).

Who was Blackbird?

Makadebineshii, Chief Blackbird, is an elusive presence in both the primary and secondary historical record. In the 1840s, he emerges as the practical leader of the largest faction of the La Pointe Band, but outside of Bad River, where the main tribal offices bear his name, he is not a well-known figure in the history of the Chequamegon area at all.

Unlike, Chief Buffalo, Blackbird did not sign many treaties, did not frequently correspond with government officials, and is not remembered favorably by whites. In fact, his portrayal in the primary sources is often negative. So then, why did the majority of the Ojibwe back Blackbird at the 1855 payment? The answer is probably the same reason why many whites disliked him. He was an unwavering defender of Ojibwe sovereignty, he adhered to his traditional culture, and he refused to cooperate with the United States Government when he felt the land and treaty rights of his people were being violated.

One needs to be careful drawing too sharp a contrast between Blackbird and Buffalo, however. The two men worked together at times, and Blackbird’s son James, later identified his father as Buffalo’s pipe carrier. Their central goals were the same, and both labored hard on behalf of their people, but Buffalo was much more willing to work with the Government. For instance, Buffalo’s response in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, when the fate of Ojibwe removal was undecided, was to go to the president for help. Blackbird, meanwhile, was part of the group of Ojibwe chiefs who hoped to escape the Americans by joining Chief Zhingwaakoons at Garden River on the Canadian side of Sault Ste. Marie.

Still, I hesitate to simply portray Blackbird and Buffalo as rivals. If for no other reason, I still haven’t figured out what their exact relationship was. I have not been able to find any reference to Blackbird’s father, his clan, or really anything about him prior to the 1840s. For a while, I was working under the hypothesis that he was the son of Dagwagaane (Tugwaganay/Goguagani), the old Crane Clan chief (brother of Madeline Cadotte), who usually camped by Bad River, and was often identified as Buffalo’s second chief.

However, that seems unlikely given this testimony from James Blackbird that identifies Oshkinawe, a contemporary of the elder Blackbird, as the heir of Guagain (Dagwagaane):

Statement of James Blackbird: Condition of Indian affairs in Wisconsin: hearings before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, [61st congress, 2d session], on Senate resolution, Issue 263. pg 203. (Digitized by Google Books).

It seems Commissioner Manypenny left La Pointe before the issue was entirely settled, because a month later, we find a draft letter from Blackbird to the Commissioner transcribed in Wheeler’s hand:

Mushkesebe River Oct. 1855

Blackbird. Principal chief of the Mushkisibi-river Indians to Hon. G. Manepenny Com. of Indian Affairs Washington City.

Father; Although I have seen you face to face, & had the privilege to talking freely with you, we did not do all that is to be attended to about our affairs. We have not forgotten the words you spoke to us, we still keep them in our minds. We remember you told us not to listen to all the foolish stories that was flying about–that we should listen to what was good, and mind nothing about anything else. While we listened to your advice we kept one ear open and the other shut, & [We?] kept retained all you spoke said in our ears, and. Your words are still ringing in our ears. The night that you left the sound of the paddles in boat that carried you away from us was had hardly gone ceased before the minds of some of the chiefs was were tuned by the traders from the advice you gave, but we did not listen to them. Ja-jig-wy-ong, (Buffalo’s son) son says that he & Naganub asked Mr. Gilbert if they could go to Washington to see about the affairs of the Indians. Now father, we are sure you opened your heart freely to us, and did not keep back anything from us that is for our good. We are sure you had a heart to feel for us & sympathise with us in our trials, and we think that if there is any important business to be attended to you would not have kept it secret & hid it from us, we should have knew it. If I am needed to go to Washington, to represent the interests of our people, I am ready to go. The ground that we took against about our old debts, I am ready to stand shall stand to the last. We are now in Mr. Wheelers house where you told us to go, if we had any thing to say, as Mr. W was our friend & would give us good advice. We have done so. All the chiefs & people for whom I spoke, when you were here, are of the same mind. They all requested before they left that I should go to Washington & be sure & hold on to Mr. Wheeler as one to go with me, because he has always been our steadfast friend and has al helped us in our troubles. There is another thing, my father, which makes us feel heavy hearted. This is about our reservation. Although you gave us definite instructions about it, there are some who are trying to shake our reserve all to pieces. A trader is already here against our will & without any authority from Govt, has put him up a store house & is trading with our people. In open council also at La Pointe when speaking for our people, I said we wanted Mr. W to be our teacher, but now another is come which whom we don’t want, and is putting up a house. We supposed when you spoke to us about a teacher being permitted to live among us, you had reference to the one we now have, one is enough, we do not wish to have any more, especially of the kind of him who has just come. We forbid him to build here & showed him the paper you gave us, but he said that paper permitted him rather than forbid him to come. If the chiefs & young men did not remember what you told them to keep quiet there would already be have been war here. There is always trouble when there two religions come together. Now we are weak and can do nothing and we want you to help us extend your arms to help us. Your arms can extend even to us. We want you to pity & help us in our trouble. Now we wish to know if we are wanted, or are permitted, three or four of us to come to which Washington & see to our interests, and whether our debts will be paid. We would like to have you write us immediately & let us know what your will is, when you will have us come, if at all. One thing further. We do not want any account to be allowed that was not presented to us for us to pass our opin us to pass judgement on, we hear that some such accounts have been smuggled in without our knowledge or consent.

The letter is unsigned, lacks a specific date, and has numerous corrections, which indicate it was a draft of the actual letter sent to Manypenny. This draft is found in the Wheeler Family Papers in the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center. As interesting as it is, Blackbird’s letter raises more questions than answers. Why is the chief so anxious to go to Washington? What are the other chiefs doing? What are these accounts being smuggled in? Who are the people trying to shake the reservation to pieces and what are they doing? Perhaps most interestingly, why does Blackbird, a practitioner of traditional religion, think he will get help from a missionary?

For the answer to that last question, let’s take a look at the situation of Leonard H. Wheeler. When Wheeler, and his wife, Harriet came here in 1841, the La Pointe mission of Sherman Hall was already a decade old. In a previous post, we looked at Hall’s attitudes toward the Ojibwe and how they didn’t earn him many converts. This may have been part of the reason why it was Wheeler, rather than Hall, who in 1845 spread the mission to Odanah where the majority of the La Pointe Band were staying by their gardens and rice beds and not returning to Madeline Island as often as in the past.

When compared with his fellow A.B.C.F.M. missionaries, Sherman Hall, Edmund Ely, and William T. Boutwell, Wheeler comes across as a much more sympathetic figure. He was as unbending in his religion as the other missionaries, and as committed to the destruction of Ojibwe culture, but in the sources, he seems much more willing than Hall, Ely, or Boutwell to relate to Ojibwe people as fellow human beings. He proved this when he stood up to the Government during the Sandy Lake Tragedy (while Hall was trying to avoid having to help feed starving people at La Pointe). This willingness to help the Ojibwe through political difficulties is mentioned in the 1895 book In Unnamed Wisconsin by John N. Davidson, based on the recollections of Harriet Wheeler:

From In Unnamed Wisconsin pg. 170 (Digitized by Google Books).

So, was Wheeler helping Blackbird simply because it was the right thing to do? We would have to conclude yes, if we ended it here. However, Blackbird’s letter to Manypenny was not alone. Wheeler also wrote his own to the Commissioner. Its draft is also in the Wheeler Family Papers, and it betrays some ulterior motives on the part of the Odanah-based missionary:

example not to meddle with other peoples business.

Mushkisibi River Oct. 1855

L.H. Wheeler to Hon. G.W. Manypenny

Dear Sir. In regard to what Blackbird says about going to Washington, his first plan was to borrow money here defray his expenses there, & have me start on. Several of the chiefs spoke to me before soon after you left. I told them about it if it was the general desire. In regard to Black birds Black Bird and several of the chiefs, soon after you left, spoke to me about going to Washington. I told them to let me know what important ends were to be affected by going, & how general was the desire was that I should accompany such a delegation of chiefs. The Indians say it is the wish of the Grand Portage, La Pointe, Ontonagun, L’anse, & Lake du Flambeaux Bands that wish me to go. They say the trader is going to take some of their favorite chiefs there to figure for the 90,000 dollars & they wish to go to head them off and save some of it if possible. A nocturnal council was held soon after you left in the old mission building, by some of the traders with some of the Indians, & an effort was made to get them Indians to sign a paper requesting that Mr. H.M. Rice be paid $5000 for goods sold out of the 90,000 that be the Inland Indians be paid at Chippeway River & that the said H.M. Rice be appointed agent. The Lake du Flambeau Indians would not come into the [meeting?] & divulged the secret to Blackbird. They wish to be present at [Shington?] to head off [sail?] in that direction. I told Blackbird I thought it doubtful whether I could go with him, was for borrowing money & starting immediately down the Lake this fall, but I advised him to write you first & see what you thought about the desirability of his going, & know whether his expenses would be born. Most of the claimants would be dread to see him there, & of course would not encourage his going. I am not at all certain certain that I will be [considered?] for me to go with Blackbird, but if the Dept. think it desirable, I will take it into favorable consideration. Mr. Smith said he should try to be there & thought I had better go if I could. The fact is there is so much fraud and corruption connected with this whole matter that I dread to have anything to do with it. There is hardly a spot in the whole mess upon which you can put your finger without coming in contact with the deadly virus. In regard to the Priest’s coming here, The trader the Indians refer to is Antoine [Gordon?], a half breed. He has erected a small store house here & has brought goods here & acknowledges that he has sold them and defies the Employees. Mssrs. Van Tassel & Stoddard to help [themselves?] if they can. He is a liquer-seller & a gambler. He is now putting up a house of worship, by contract for the Catholic Priest. About what the Indians said about his coming here is true. In order to ascertain the exact truth I went to the Priest myself, with Mr. Stoddard, Govt [S?] man Carpenter. His position is that the Govt have no right to interfere in matters of religion. He says he has a right to come here & put up a church if there are any of his faith here, and they permit him to build on his any of their claims. He says also that Mr. Godfrey got permission of Mr. Gilbert to come here. I replied to him that the Commissioner told me that it was not the custom of the Gov. to encourage but one denomination of Christians in a place. Still not knowing exactly the position of Govt upon the subject, I would like to ask the following questions.

1. When one Missionary Society has already commenced labors a station among a settlement of Indians, and a majority of the Indians people desire to have him for their religious teacher, have missionaries of another denomination a right to come in and commence a missionary establishment in the same settlement?

Have they a right to do it against the will of a majority of the people?

Have they a right to do it in any case without the permission of the Govt?

Has any Indian a right, by sold purchase, lease or otherwise a right to allow a missionary to build on or occupy a part of his claim? Or has the same missionary a right to arrange with several missionaries Indians for to occupy by purchase or otherwise a part of their claims severally? I ask these questions, not simply with reference to the Priest, but with regard to our own rights & privileges in case we wish to commence another station at any other point on the reserve. The coming of the Catholic Priest here is a [mere stroke of policy, concocted?] in secret by such men as Mssrs. Godfrey & Noble to destroy or cripple the protestant mission. The worst men in the country are in favor of the measure. The plan is under the wing of the priest. The plan is to get in here a French half breed influence & then open the door for the worst class of men to come in and com get an influence. Some of the Indians are put up to believe that the paper you gave Blackbird is a forgery put up by the mission & Govt employ as to oppress their mission control the Indians. One of the claimants, for whom Mr. Noble acts as attorney, told me that the same Mr. Noble told him that the plan of the attorneys was to take the business of the old debts entirely out of your hands, and as for me, I was a fiery devil they when they much[?] tell their report was made out, & here what is to become of me remains to be seen. Probably I am to be hung. If so, I hope I shall be summoned to Washington for [which purpose?] that I may be held up in [t???] to all missionaries & they be [warned?] by my […]

The dramatic ending to this letter certainly reveals the intensity of the situation here in the fall of 1855. It also reveals the intensity of Wheeler’s hatred for the Roman Catholic faith, and by extension, the influence of the Catholic mix-blood portion of the La Pointe Band. This makes it difficult to view the Protestant missionary as any kind of impartial advocate for justice. Whatever was going on, he was right in the middle of it.

So, what did happen here?

From Morse, McElroy, and these two letters, it’s clear that Blackbird was doing whatever he could to stop the Government from paying annuity funds directly to the creditors. According to Wheeler, these men were led by U.S. Senator and fur baron Henry Mower Rice. It’s also clear that a significant minority of the Ojibwe, including most of the La Pointe mix-bloods, did not want to see the money go directly to the chiefs for disbursement.

I haven’t uncovered whether the creditors’ claims were accepted, or what Manypenny wrote back to Blackbird and Wheeler, but it is not difficult to guess what the response was. Wheeler, a Massachusetts-born reformist, had been able to influence Indian policy a few years earlier during the Whig administration of Millard Fillmore, and he may have hoped for the same with the Democrats. But this was 1855. Kansas was bleeding, the North was rapidly turning toward “Free Soil” politics, and the Dred Scott case was only a few months away. Franklin Pierce, a Southern-sympathizer had won the presidency in a landslide (losing only Massachusetts and three other states) in part because he was backed by Westerners like George Manypenny and H. M. Rice. To think the Democratic “Indian Ring,” as it was described above, would listen to the pleas coming from Odanah was optimistic to say the least.

“[E]xample not to meddle with other peoples business” is written at the top of Wheeler’s draft. It is his handwriting, but it is much darker than the rest of the ink and appears to have been added long after the fact. It doesn’t say it directly, but it seems pretty clear Wheeler didn’t look back on this incident as a success. I’ll keep looking for proof, but for now I can say with confidence that the request for a Washington delegation was almost certainly rejected outright.

So who are the good guys in this situation?

If we try to fit this story into the grand American narrative of Manifest Destiny and the systematic dispossession of Indian peoples, then we would have to conclude that this is a story of the Ojibwe trying to stand up for their rights against a group of corrupt traders. However, I’ve never had much interest in this modern “Dances With Wolves” version of Indian victimization. Not that it’s always necessarily false, but this narrative oversimplifies complex historical events, and dehumanizes individual Indians as much as the old “hostile savages” framework did. That’s why I like to compare the Chequamegon story more to the Canadian narrative of Louis Riel and company than to the classic American Little Bighorn story. The dispossession and subjugation of Native peoples is still a major theme, but it’s a lot messier. I would argue it’s a lot more accurate and more interesting, though.

So let’s evaluate the individuals involved rather than the whole situation by using the most extreme arguments one could infer from these documents and see if we can find the truth somewhere in the middle:

Henry Mower Rice (Wikimedia Images)

Henry M. Rice

The case against: H. M. Rice was businessman who valued money over all else. Despite his close relationship with the Ho-Chunk people, he pressed for their 1847 removal because of the enormous profits it brought. A few years later, he was the driving force behind the Sandy Lake removal of the Ojibwe. Both of these attempted removals came at the cost of hundreds of lives. There is no doubt that in 1855, Rice was simply trying to squeeze more money out of the Ojibwe.

The case for: H. M. Rice was certainly a businessman, and he deserved to be paid the debts owed him. His apparent actions in 1855 are the equivalent of someone having a lien on a house or car. That money may have justifiably belonged to him. As for his relationship with the Ojibwe, Rice continued to work on their behalf for decades to come, and can be found in 1889 trying to rectify the wrongs done to the Lake Superior bands when the reservations were surveyed.

From In Unnamed Wisconsin pg. 168. It’s not hard to figure out which Minnesota senator is being referred to here in this 1895 work informed by Harriet Wheeler. (Digitized by Google Books).

Antoine Gordon from Noble Lives of a Noble Race (pg. 207) published by the St. Mary’s Industrial School in Odanah.

Antoine Gordon

The case against: Antoine Gaudin (Gordon) was an unscrupulous trader and liquor dealer who worked with H. M. Rice to defraud his Ojibwe relatives during the 1855 annuities. He then tried to steal land and illegally squat on the Bad River Reservation against the expressed wishes of Chief Blackbird and Commissioner Manypenny.

The case for: Antoine Gordon couldn’t have been working against the Ojibwe since he was an Ojibwe man himself. He was a trader and was owed debts in 1855, but most of the criticism leveled against him was simply anti-Catholic libel from Leonard Wheeler. Antoine was a pious Catholic, and many of his descendants became priests. He built the church at Bad River because there were a number of people in Bad River who wanted a church. Men like Gordon, Vincent Roy Jr., and Joseph Gurnoe were not only crucial to the development of Red Cliff (as well as Superior and Gordon, WI) as a community, they were exactly the type of leaders the Ojibwe needed in the post-1854 world.

Portrait of Naw-Gaw-Nab (The Foremost Sitter) n.d by J.E. Whitney of St. Paul (Smithsonian)

Naaganab

The case against: Chiefs like Naaganab and Young Buffalo sold their people out for a quick buck. Rather than try to preserve the Ojibwe way of life, they sucked up to the Government by dressing like whites, adopting Catholicism, and using their favored position for their own personal gain and to bolster the position of their mix-blooded relatives.

The case for: If you frame these events in terms of Indians vs. Traders, you then have to say that Naaganab, Young Buffalo, and by extension Chief Buffalo were “Uncle Toms.” The historical record just doesn’t support this interpretation. The elder Buffalo and Naaganab each lived for nearly a century, and they each strongly defended their people and worked to preserve the Ojibwe land base. They didn’t use the same anti-Government rhetoric that Blackbird used at times, but they were working for the same ends. In fact, years later, Naaganab abandoned his tactic of assimilation as a means to equality, telling Rice in 1889:

“We think the time is past when we should take a hat and put it on our heads just to mimic the white man to adopt his custom without being allowed any of the privileges that belong to him. We wish to stand on a level with the white man in all things. The time is past when my children should stand in fear of the white man and that is almost all that I have to say (Nah-guh-nup pg. 192).”

Leonard H. Wheeler

L. H. Wheeler (WHS Image ID 66594)

The case against: Leonard Wheeler claimed to be helping the Ojibwe, but really he was just looking out for his own agenda. He hated the Catholic Church and was willing to do whatever it took to keep the Catholics out of Bad River including manipulating Blackbird into taking up his cause when the chief was the one in need. Wheeler couldn’t mind his own business. He was the biggest enemy the Ojibwe had in terms of trying to maintain their traditions and culture. He didn’t care about Blackbird. He just wanted the free trip to Washington.

The case for: In contrast to Sherman Hall and some of the other missionaries, Leonard Wheeler was willing to speak up forcefully against injustice. He showed this during the Sandy Lake removal and again during the 1855 payment. He saw the traders trying to defraud the Ojibwe and he stood up against it. He supported Blackbird in the chief’s efforts to protect the territorial integrity of the Bad River reservation. At a risk to his own safety, he chose to do the right thing.

Blackbird

The case against: Blackbird was opportunist trying to seize power after Buffalo’s death by playing to the outdated conservative impulses of his people at a time when they should have been looking to the future rather than the past. This created harmful factional differences that weakened the Ojibwe position. He wanted to go to Washington because it would make him look stronger and he manipulated Wheeler into helping him.

The case for: From the 1840s through the 1860s, the La Pointe Ojibwe had no stronger advocate for their land, culture, and justice than Chief Blackbird. While other chiefs thought they could work with a government that was out to destroy them, Blackbird never wavered, speaking consistently and forcefully for land and treaty rights. The traders, and other enemies of the Ojibwe, feared him and tried to keep their meetings and Washington trip secret from him, but he found out because the majority of the people supported him.

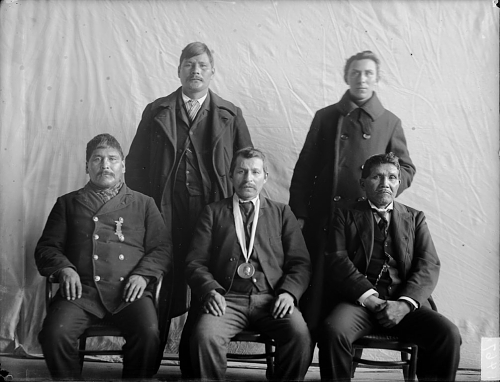

I’ve yet to find a picture of Blackbird, but this 1899 Bad River delegation to Washington included his son James (bottom right) along with Henry and Jack Condecon, George Messenger, and John Medegan–all sons and/or grandsons of signers of the Treaty of 1854 (Photo by De Lancey Gill; Smithsonian Collections).

Final word for now…

An entire book could be written about the 1855 annuity payments, and like so many stories in Chequamegon History, once you start the inquiry, you end up digging up more questions than answers. I can’t offer a neat and tidy explanation for what happened with the debts. I’m inclined to think that if Henry Rice was involved it was probably for his own enrichment at the expense of the Ojibwe, but I have a hard time believing that Buffalo, Jayjigwyong, Naaganab, and most of the La Pointe mix-bloods would be doing the same. Blackbird seems to be the hero in this story, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if there was a political component to his actions as well. Wheeler deserves some credit for his defense of a position that alienated him from most area whites, but we have to take anything he writes about his Catholic neighbors with a grain of salt.

As for the Blackbird-Wheeler relationship, showcasing these two fascinating letters was my original purpose in writing this post. Was Blackbird manipulating Wheeler, was Wheeler manipulating Blackbird, or was neither manipulating the other? Could it be that the zealous Christian missionary and the stalwart “pagan” chief, were actually friends? What do you think?

Sources:

Davidson, J. N., and Harriet Wood Wheeler. In Unnamed Wisconsin: Studies in the History of the Region between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi. Milwaukee, WI: S. Chapman, 1895. Print.

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

McElroy, Crocket. “An Indian Payment.” Americana v.5. American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Pupil’s of St. Mary’s, and Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration. Noble Lives of a Noble Race. Minneapolis: Brooks, 1909. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Oshogay

August 12, 2013

At the most recent count, Chief Buffalo is mentioned in over two-thirds of the posts here on Chequamegon History. That’s the most of anyone listed so far in the People Index. While there are more Buffalo posts on the way, I also want to draw attention to some of the lesser known leaders of the La Pointe Band. So, look for upcoming posts about Dagwagaane (Tagwagane), Mizay, Blackbird, Waabojiig, Andeg-wiiyas, and others. I want to start, however, with Oshogay, the young speaker who traveled to Washington with Buffalo in 1852 only to die the next year before the treaty he was seeking could be negotiated.

I debated whether to do this post, since I don’t know a lot about Oshogay. I don’t know for sure what his name means, so I don’t know how to spell or pronounce it correctly (in the sources you see Oshogay, O-sho-ga, Osh-a-ga, Oshaga, Ozhoge, etc.). In fact, I don’t even know how many people he is. There were at least four men with that name among the Lake Superior Ojibwe between 1800 and 1860, so much like with the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search, the key to getting Oshogay’s history right is dependent on separating his story from those who share his name.

In the end, I felt that challenge was worth a post in its own right, so here it is.

Getting Started

According to his gravestone, Oshogay was 51 when he died at La Pointe in 1853. That would put his birth around 1802. However, the Ojibwe did not track their birthdays in those days, so that should not be considered absolutely precise. He was considered a young man of the La Pointe Band at the time of his death. In my mind, the easiest way to sort out the information is going to be to lay it out chronologically. Here it goes:

1) Henry Schoolcraft, United States Indian Agent at Sault Ste. Marie, recorded the following on July 19, 1828:

Oshogay (the Osprey), solicited provisions to return home. This young man had been sent down to deliver a speech from his father, Kabamappa, of the river St. Croix, in which he regretted his inability to come in person. The father had first attracted my notice at the treaty of Prairie du Chien, and afterwards received a small medal, by my recommendation, from the Commissioners at Fond du Lac. He appeared to consider himself under obligations to renew the assurance of his friendship, and this, with the hope of receiving some presents, appeared to constitute the object of his son’s mission, who conducted himself with more modesty and timidity before me than prudence afterwards; for, by extending his visit to Drummond Island, where both he and his father were unknown, he got nothing, and forfeited the right to claim anything for himself on his return here.

I sent, however, in his charge, a present of goods of small amount, to be delivered to his father, who has not countenanced his foreign visit.

Oshogay is a “young man.” A birth year of 1802 would make him 26. He is part of Gaa-bimabi’s (Kabamappa’s) village in the upper St. Croix country.

2) In June of 1834, Edmund Ely and W. T. Boutwell, two missionaries, traveled from Fond du Lac (today’s Fond du Lac Reservation near Cloquet) down the St. Croix to Yellow Lake (near today’s Webster, WI) to meet with other missionaries. As they left Gaa-bimabi’s (Kabamappa’s) village near the head of the St. Croix and reached the Namekagon River on June 28th, they were looking for someone to guide them the rest of the way. An old Ojibwe man, who Boutwell had met before at La Pointe, and his son offered to help. The man fed the missionaries fish and hunted for them while they camped a full day at the mouth of the Namekagon since the 29th was a Sunday and they refused to travel on the Sabbath. On Monday the 30th, the reembarked, and Ely recorded in his journal:

The man, whose name is “Ozhoge,” and his son embarked with us about 1/2 past 9 °clk a.m. The old man in the bow and myself steering. We run the rapids safely. At half past one P. M. arrived at the mouth of Yellow River…

Ozhoge is an “old man” in 1834, so he couldn’t have been born in 1802. He is staying on the Namekagon River in the upper St. Croix country between Gaa-bimabi and the Yellow Lake Band. He had recently spent time at La Pointe.

3) Ely’s stay on the St. Croix that summer was brief. He was stationed at Fond du Lac until he eventually wore out his welcome there. In the 1840s, he would be stationed at Pokegama, lower on the St. Croix. During these years, he makes multiple references to a man named Ozhogens (a diminutive of Ozhoge). Ozhogens is always found above Yellow River on the upper St. Croix.

Ozhogens has a name that may imply someone older (possibly a father or other relative) lives nearby with the name Ozhoge. He seems to live in the upper St. Croix country. A birth year of 1802 would put him in his forties, which is plausible.

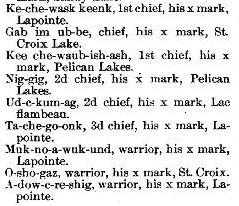

Ke-che-wask keenk (Gichi-weshki) is Chief Buffalo. Gab-im-ub-be (Gaa-bimabi) was the chief Schoolcraft identified as the father of Oshogay. Ja-che-go-onk was a son of Chief Buffalo.

4) On August 2, 1847, the United States and the Mississippi and Lake Superior Ojibwe concluded a treaty at Fond du Lac. The US Government wanted Ojibwe land along the nation’s border with the Dakota Sioux, so it could remove the Ho-Chunk people from Wisconsin to Minnesota.

Among the signatures, we find O-sho-gaz, a warrior from St. Croix. This would seem to be the Ozhogens we meet in Ely.

Here O-sho-gaz is clearly identified as being from St. Croix. His identification as a warrior would probably indicate that he is a relatively young man. The fact that his signature is squeezed in the middle of the names of members of the La Pointe Band may or may not be significant. The signatures on the 1847 Treaty are not officially grouped by band, but they tend to cluster as such.

5) In 1848 and 1849 George P. Warren operated the fur post at Chippewa Falls and kept a log that has been transcribed and digitized by the University of Wisconsin Eau Claire. He makes several transactions with a man named Oshogay, and at one point seems to have him employed in his business. His age isn’t indicated, but the amount of furs he brings in suggests that he is the head of a small band or large family. There were multiple Ojibwe villages on the Chippewa River at that time, including at Rice Lake and Lake Shatac (Chetek). The United States Government treated with them as satellite villages of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band.

Based on where he lives, this Oshogay might not be the same person as the one described above.

6) In December 1850, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in the case Oshoga vs. The State of Wisconsin, that there were a number of irregularities in the trial that convicted “Oshoga, an Indian of the Chippewa Nation” of murder. The court reversed the decision of the St. Croix County circuit court. I’ve found surprisingly little about this case, though that part of Wisconsin was growing very violent in the 1840s as white lumbermen and liquor salesmen were flooding the country.

Pg 56 of Containing cases decided from the December term, 1850, until the organization of the separate Supreme Court in 1853: Volume 3 of Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Wisconsin: With Tables of the Cases and Principal Matters, and the Rules of the Several Courts in Force Since 1838, Wisconsin. Supreme Court Authors: Wisconsin. Supreme Court, Silas Uriah Pinney (Google Books).

The man killed, Alexander Livingston, was a liquor dealer himself.

Alexander Livingston, a man who in youth had had excellent advantages, became himself a dealer in whisky, at the mouth of Wolf creek, in a drunken melee in his own store was shot and killed by Robido, a half-breed. Robido was arrested but managed to escape justice.

~From Fifty Years in the Northwest by W.H.C Folsom

Several pages later, Folsom writes:

At the mouth of Wolf creek, in the extreme northwestern section of this town, J. R. Brown had a trading house in the ’30s, and Louis Roberts in the ’40s. At this place Alex. Livingston, another trader, was killed by Indians in 1849. Livingston had built him a comfortable home, which he made a stopping place for the weary traveler, whom he fed on wild rice, maple sugar, venison, bear meat, muskrats, wild fowl and flour bread, all decently prepared by his Indian wife. Mr. Livingston was killed by an Indian in 1849.

Folsom makes no mention of Oshoga, and I haven’t found anything else on what happened to him or Robido (Robideaux?).

It’s hard to say if this Oshoga is the Ozhogen’s of Ely’s journals or the Oshogay of Warren’s. Wolf Creek is on the St. Croix, but it’s not far from the Chippewa River country either, and the Oshogay of Warren seems to have covered a lot of ground in the fur trade. Warren’s journal, linked in #4, contains a similar story of a killing and “frontier justice” leading to lynch mobs against the Ojibwe. To escape the violence and overcrowding, many Ojibwe from that part of the country started to relocate to Fond du Lac, Lac Courte Oreilles, or La Pointe/Bad River. La Pointe is also where we find the next mention of Oshogay.

7) From 1851 to 1853, a new voice emerged loudly from the La Pointe Band in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. It was that of Buffalo’s speaker Oshogay (or O-sho-ga), and he spoke out strongly against Indian Agent John Watrous’ handling of the Sandy Lake payments (see this post) and against Watrous’ continued demands for removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. There are a number of documents with Oshogay’s name on them, and I won’t mention all of them, but I recommend Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren and Howard Paap’s Red Cliff, Wisconsin as two places to get started.

Chief Buffalo was known as a great speaker, but he was nearing the end of his life, and it was the younger chief who was speaking on behalf of the band more and more. Oshogay represented Buffalo in St. Paul, co-wrote a number of letters with him, and most famously, did most of the talking when the two chiefs went to Washington D.C. in the spring of 1852 (at least according to Benjamin Armstrong’s memoir). A number of secondary sources suggest that Oshogay was Buffalo’s son or son-in-law, but I’ve yet to see these claims backed up with an original document. However, all the documents that identify by band, say this Oshogay was from La Pointe.

The Wisconsin Historical Society has digitized four petitions drafted in the fall of 1851 and winter of 1852. The petitions are from several chiefs, mostly of the La Pointe and Lac Courte Oreilles/Chippewa River bands, calling for the removal of John Watrous as Indian Agent. The content of the petitions deserves its own post, so for now we’ll only look at the signatures.

November 6, 1851 Letter from 30 chiefs and headmen to Luke Lea, Commissioner of Indian Affairs: Multiple villages are represented here, roughly grouped by band. Kijiueshki (Buffalo), Jejigwaig (Buffalo’s son), Kishhitauag (“Cut Ear” also associated with the Ontonagon Band), Misai (“Lawyerfish”), Oshkinaue (“Youth”), Aitauigizhik (“Each Side of the Sky”), Medueguon, and Makudeuakuat (“Black Cloud”) are all known members of the La Pointe Band. Before the 1850s, Kabemabe (Gaa-bimabi) and Ozhoge were associated with the villages of the Upper St. Croix.

November 8, 1851, Letter from the Chiefs and Headmen of Chippeway River, Lac Coutereille, Puk-wa-none, Long Lake, and Lac Shatac to Alexander Ramsey, Superintendent of Indian Affairs: This letter was written from Sandy Lake two days after the one above it was written from La Pointe. O-sho-gay the warrior from Lac Shatac (Lake Chetek) can’t be the same person as Ozhoge the chief unless he had some kind of airplane or helicopter back in 1851.

Undated (Jan. 1852?) petition to “Our Great Father”: This Oshoga is clearly the one from Lake Chetek (Chippewa River).

Undated (Jan. 1852?) petition: These men are all associated with the La Pointe Band. Osho-gay is their Speaker.

In the early 1850s, we clearly have two different men named Oshogay involved in the politics of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. One is a young warrior from the Chippewa River country, and the other is a rising leader among the La Pointe Band.

Washington Delegation July 22, 1852 This engraving of the 1852 delegation led by Buffalo and Oshogay appeared in Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians. Look for an upcoming post dedicated to this image.

8) In the winter of 1853-1854, a smallpox epidemic ripped through La Pointe and claimed the lives of a number of its residents including that of Oshogay. It had appeared that Buffalo was grooming him to take over leadership of the La Pointe Band, but his tragic death left a leadership vacuum after the establishment of reservations and the death of Buffalo in 1855.

Oshogay’s death is marked in a number of sources including the gravestone at the top of this post. The following account comes from Richard E. Morse, an observer of the 1855 annuity payments at La Pointe:

The Chippewas, during the past few years, have suffered extensively, and many of them died, with the small pox. Chief O-SHO-GA died of this disease in 1854. The Agent caused a suitable tomb-stone to be erected at his grave, in La Pointe. He was a young chief, of rare promise and merit; he also stood high in the affections of his people.

Later, Morse records a speech by Ja-be-ge-zhick or “Hole in the Sky,” a young Ojibwe man from the Bad River Mission who had converted to Christianity and dressed in “American style.” Jabegezhick speaks out strongly to the American officials against the assembled chiefs:

…I am glad you have seen us, and have seen the folly of our chiefs; it may give you a general idea of their transactions. By the papers you have made out for the chiefs to sign, you can judge of their ability to do business for us. We had but one man among us, capable of doing business for the Chippewa nation; that man was O-SHO-GA, now dead and our nation now mourns. (O-SHO-GA was a young chief of great merit and much promise; he died of small-pox, February 1854). Since his death, we have lost all our faith in the balance of our chiefs…

This O-sho-ga is the young chief, associated with the La Pointe Band, who went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852.

9) In 1878, “Old Oshaga” received three dollars for a lynx bounty in Chippewa County.

Report of the Wisconsin Office of the Secretary of State, 1878; pg. 94 (Google Books)

It seems quite possible that Old Oshaga is the young man that worked with George Warren in the 1840s and the warrior from Lake Chetek who signed the petitions against Agent Watrous in the 1850s.

10) In 1880, a delegation of Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, and Lac du Flambeau chiefs visited Washington D.C. I will get into their purpose in a future post, but for now, I will mention that the chiefs were older men who would have been around in the 1840s and ’50s. One of them is named Oshogay. The challenge is figuring out which one.

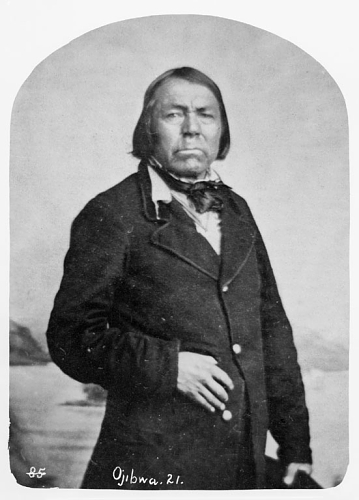

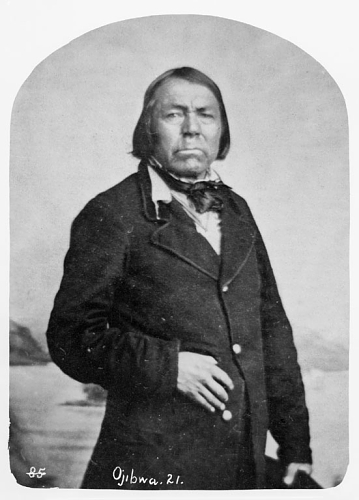

Ojibwe Delegation c. 1880 by Charles M. Bell. [Identifying information from the Smithsonian] Studio portrait of Anishinaabe Delegation posed in front of a backdrop. Sitting, left to right: Edawigijig; Kis-ki-ta-wag; Wadwaiasoug (on floor); Akewainzee (center); Oshawashkogijig; Nijogijig; Oshoga. Back row (order unknown); Wasigwanabi; Ogimagijig; and four unidentified men (possibly Frank Briggs, top center, and Benjamin Green Armstrong, top right). The men wear European-style suit jackets and pants; one man wears a peace medal, some wear beaded sashes or bags or hold pipes and other props.(Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian).

- Upper row reading from the left.

- 1. Vincent Conyer- Interpreter 1,2,4,5 ?, includes Wasigwanabi and Ogimagijig

- 2. Vincent Roy Jr.

- 3. Dr. I. L. Mahan, Indian Agent Frank Briggs

- 4. No Name Given

- 5. Geo P. Warren (Born at LaPointe- civil war vet.

- 6. Thad Thayer Benjamin Armstrong

- Lower row

- 1. Messenger Edawigijig

- 2. Na-ga-nab (head chief of all Chippewas) Kis-ki-ta-wag

- 3. Moses White, father of Jim White Waswaisoug

- 4. No Name Given Akewainzee

- 5. Osho’gay- head speaker Oshawashkogijig or Oshoga

- 6. Bay’-qua-as’ (head chief of La Corrd Oreilles, 7 ft. tall) Nijogijig or Oshawashkogijig

- 7. No name given Oshoga or Nijogijig

The Smithsonian lists Oshoga last, so that would mean he is the man sitting in the chair at the far right. However, it doesn’t specify who the man seated on the right on the floor is, so it’s also possible that he’s their Oshoga. If the latter is true, that’s also who the unknown writer of the library caption identified as Osho’gay. Whoever he is in the picture, it seems very possible that this is the same man as “Old Oshaga” from number 9.

11) There is one more document I’d like to include, although it doesn’t mention any of the people we’ve discussed so far, it may be of interest to someone reading this post. It mentions a man named Oshogay who was born before 1860 (albeit not long before).