Chief Buffalo’s Death and Conversion: A new perspective

April 18, 2014

By Leo Filipczak

Chief Buffalo died at La Pointe on September 7, 1855 amid the festivities and controversy surrounding that year’s annuity payment. Just before his death, he converted to the Catholic faith, and thus was buried inside the fence of the Catholic cemetery rather than outside with the Ojibwe people who kept traditional religious practices.

His death was noted by multiple written sources at the time, but none seemed to really dive into the motives and symbolism behind his conversion. This invited speculation from later scholars, and I’ve heard and proposed a number of hypotheses about why Buffalo became Catholic.

Now, a newly uncovered document, from a familiar source, reveals new information. And while it may diminish the symbolic impact of Buffalo’s conversion, it gives further insight into an important man whose legend sometimes overshadows his life.

Buffalo’s Obituary

The most well-known account of Buffalo’s death is from an obituary that appeared in newspapers across the country. It was also recorded in the essay, The Chippewas of Lake Superior, by Dr. Richard F. Morse, who was an eyewitness to the 1855 payment.

While it’s not entirely clear if it was Morse himself who wrote the obituary, he seems to be a likely candidate. Much like the rest of Chippewas of Lake Superior, the obituary is riddled with the inaccuracies and betrays an unfamiliarity with La Pointe society:

From Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Volume 3 (Digitized by Google Books)

It isn’t hard to understand how this obituary could invite several interpretations, especially when combined with other sources of the era and the biases of 20th and 21st-century investigators (myself included) who are always looking for a symbolic or political explanation.

Here, we will evaluate these interpretations.

Was Buffalo sending a message to the Ojibwe about the future?

The obituary states, “No tongue like Buffalo’s could control and direct the different bands.” An easy interpretation might suggest that he was trying to send a message that assimilation to white culture was the way of the future, and that all the Ojibwe should follow his lead. We do see suggestions in the writings of Henry Schoolcraft and William Warren that might support this conclusion.

The problem with this interpretation is that no Ojibwe leader, not even Buffalo, had that level of influence. Even if he wanted to, which would have been completely contrary to Ojibwe tolerance of religious pluralism, he could not have pulled a Henry VIII and converted his whole nation.

In fact, by 1855, Buffalo’s influence was at an all-time low. Recent scholarship has countered the image crafted by Benjamin Armstrong and others, of a chief whose trip to Washington and leadership through the Treaty of 1854 made him more powerful in his final years. Consider this 1852 depiction in Wagner and Scherzer’s Reisen in Nordamerika:

…Here we have the hereditary Chippewa chief, whose generations (totem) are carved in the ancient birch bark,** giving us profuse thanks for just a modest silver coin and a piece of dry cloth. What time can bring to a ruler!

So, did Buffalo decide in the last days of his life that Christianity was superior to traditional ways?

The reason why the obituary and other contemporary sources don’t go into the reasons for Buffalo’s conversion was because they hold the implicit assumption that Christianity is the one true religion. Few 19th-century American readers would be asking why someone would convert. It was a given. 160 years later, we don’t make this assumption anymore, but it should be explored whether or not this was purely a religious decision on Buffalo’s part.

I have a difficult time believing this. Buffalo had nearly 100 years to convert to Christianity if he’d wanted to. The traditional Ojibwe, in general, were extremely resistant to conversion, and there are several sources depicting Buffalo as a leader in the Midewiwin. This continuation of the above quote from Wagner and Scherzer shows Buffalo’s relationship to those who felt the Ojibwe needed Christianity.

Strangely, we later learned that the majestic Old Buffalo was violently opposed for years to the education and spiritual progress of the Indians. Probably, it’s because he suspected a better instructed generation would no longer obey. Presently, he tacitly accepts the existence of the school and even visits sometimes, where like ourselves, he has the opportunity to see the gains made in this school with its stubborn, fastidious look of an old German high council.

Accounts like this suggest a political rather than a spiritual motive.

So, did Buffalo’s convert for political rather than spiritual reasons?

Some have tied Buffalo’s conversion to a split in the La Pointe Band after the Treaty of 1854, and it’s important to remember all the heated factional divisions that rose up during the 1855 payment. Until recently, my personal interpretation would have been that Buffalo’s conversion represented a final break with Blackbird and the other Bad River chiefs. Perhaps Buffalo felt alienated from most of the traditional Ojibwe after he found himself in the minority over the issue of debt payments. His final speech was short, and reveals disappointment and exasperation on the part of the aged leader.

By the time of his death, most of his remaining followers, including the mix-blooded Ojibwe of La Pointe, and several of his children were Catholic, while most Ojibwe remained traditional. Perhaps there was additional jealousy over clauses in the treaty that gave Buffalo a separate reservation at Red Cliff and an additional plot of land. We see hints of this division in the obituary when an unidentified Ojibwe man blames the government for Buffalo’s death. This all could be seen as a separation forming between a Catholic Red Cliff and a traditional Bad River.

This interpretation would be perfect if it wasn’t grossly oversimplified. The division didn’t just happen in 1854. The La Pointe Band had always really been several bands. Those, like Buffalo’s, that were most connected to the mix-bloods and traders stayed on the Island more, and the others stayed at Bad River more. Still, there were Catholics at Bad River, and traditional Ojibwe on the Island. This dynamic and Buffalo’s place in it, were well-established. He did not have to convert to be with the “Catholic” faction. He had been in it for years.

Some have questioned whether Buffalo really converted at all. From a political point of view, one could say his conversion was really a show for Commissioner Manypenny to counter Blackbird’s pants (read this post if you don’t know what I’m talking about). I see that as overly cynical and out of character for Buffalo. I also don’t think he was ignorant of what conversion meant. He understood the gravity of what he was deciding, and being a ninety-year-old chief, I don’t think he would have felt pressured to please anyone.

So if it wasn’t symbolic, political, or religious zeal, why did Buffalo convert?

The Kohl article

As he documented the 1855 payment, Richard Morse’s ethnocentric values prevented any meaningful understanding of Ojibwe culture. However, there was another white outsider present at La Pointe that summer who did attempt to understand Ojibwe people as fellow human beings. He had come all the way from Germany.

The name of Johann Georg Kohl will be familiar to many readers who know his work Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings Around Lake Superior (1860). Kohl’s desire to truly know and respect the people giving him information left us with what I consider the best anthropological writing ever done on this part of the world.

My biggest complaint with Kohl is that he typically doesn’t identify people by name. Maangozid, Gezhiiyaash, and Zhingwaakoons show up in his work, but he somehow manages to record Blackbird’s speech without naming the Bad River chief. In over 100 pages about life at La Pointe in 1855, Buffalo isn’t mentioned at all.

So, I was pretty excited to find an untranslated 1859 article from Kohl on Google Books in a German-language weekly. The journal, Das Ausland, is a collection of writings that a would describe as ethnographic with a missionary bent.

I was even more excited as I put it through Google Translate and realized it discussed Buffalo’s final summer and conversion. It has to go out to the English-speaking world.

So without further ado, here is the first seven paragraphs of Remarks on the Conversion of the Canadian Indians and some Stories of Conversion by Johann Kohl. I apologize for any errors arising from the electronic translation. I don’t speak German and I can only hope that someone who does will see this and translate the entire article.

J. G. Kohl (Wikimedia Images)

Das Ausland.

Eine Wochenschrift

fur

Kunde des geistigen und sittlichen Lebens der Völker

[The Foreign Lands: A weekly for scholars of the moral and intellectual lives of foreign nations]

Nr. 2 8 January 1859

Remarks on the Conversion of the Canadian Indians and some Stories of Conversion

By J.G. Kohl

A few years ago, when I was on “La Pointe,” one of the so-called “Apostle Islands” in the western corner of the great Lake Superior, there still lived the old chief of the local Indians, the Chippeway or Ojibbeway people, named “Buffalo,” a man “of nearly a hundred years.” He himself was still a pagan, but many of his children, grandchildren and closest relatives, were already Christians.

I was told that even the aged old Buffalo himself “ébranlé [was shaking]”, and they told me his state of mind was fluctuating. “He thinks highly of the Christian religion,” they told me, “It’s not right to him that he and his family be of a different faith. He is afraid that he will be separated in death. He knows he will not be near them, and that not only his body should be brought to another cemetery, but also he believes his spirit shall go into another paradise away from his children.”

But Buffalo was the main representative of his people, the living embodiment, so to speak, of the old traditions and stories of his tribe, which once ranged over not only the whole group of the Apostle Islands, but also far and wide across the hunting grounds of the mainland of northern Wisconsin. His ancestors and his family, “the Totem of the Loons” (from the diver)* make claim to be the most distinguished chiefly family of the Ojibbeways. Indeed, they believe that from them and their village a far-reaching dominion once reached across all the tribes of the Ojibbeway Nation. In a word, a kind of monarchy existed with them at the center.

(*The Loon, or Diver, is a well-known large North American bird).

Old Buffalo, or Le Boeuf, as the French call him, or Pishiki, his Indian name, was like the last reflection of the long-vanished glory. He was stuck too deep in the old superstition. He was too intertwined with the Medä Order, the Wabanos, and the Jossakids, or priesthood, of his people. A conversion to Christianity would have destroyed his influence in a still mostly-pagan tribe. It would have been the equivalent of voluntarily stepping down from the throne he previously had. Therefore, in spite of his “doubting” state of mind, he could not decide to accept the act of baptism.

One evening, I visited old Buffalo in his bark lodge, and found in him grayed and stooped by the years, but nevertheless still quite a sprightly old man. Who knows what kind of fate he had as an old Indian chief on Lake Superior, passing his whole life near the Sioux, trading with the North West Company, with the British and later with the Americans. With the Wabanos and Jossakids (priests and sorcerers) he conjured for his people, and communed with the sky, but here people would call him an “old sinner.”

But still, due to his advanced age I harbored a certain amount of respect for him myself. He took me in, so kindly, and never forgot even afterwards, promising to remember my visit, as if it had been an honor for him. He told me much of the old glory of his tribe, of the origin of his people, and of his religion from the East. I gave him tobacco, and he, much more generously,gave me a beautiful fife. I later learned from the newspapers that my old host, being ill, and soon after my departure from the island, he departed from this earth. I was seized by a genuine sorrow and grieved for him. Those papers, however, reported a certain cause for consolation, in that Buffalo had said on his deathbed, he desired to be buried in a Christian way. He had therefore received Christianity and the Lord’s Supper, shortly before his death, from the Catholic missionaries, both with the last rites of the Church, and with a church funeral and burial in the Catholic cemetery, where in addition to those already resting, his family would be buried.

The story and the end of the old Buffalo are not unique. Rather, it was something rather common for the ancient pagan to proceed only on his death-bed to Christianity, and it starts not with the elderly adults on their deathbeds, but with their Indian families beginning with their young children. The parents are then won over by the children. For the children, while they are young and largely without religion, the betrayal of the old gods and laws is not so great. Therefore, the parents give allow it more easily. You yourself are probably already convinced that there is something fairly good behind Christianity, and that their children “could do quite well.” They desire for their children to attain the blessing of the great Christian God and therefore often lead them to the missionaries, although they themselves may not decide to give up their own ingrained heathen beliefs. The Christians, therefore, also prefer to first contact the youth, and know well that if they have this first, the parents will follow sooner or later because they will not long endure the idea that they are separated from their children in the faith. Because they believe that baptism is “good medicine” for the children, they bring them very often to the missionaries when they are sick…

Das Ausland: Wochenschrift für Länder- u. Völkerkunde, Volumes 31-32. Only about a quarter of the article is translated above. The remaining pages largely consist of Kohl’s observations on the successes and failures of missionary efforts based on real anecdotes.

Conclusion

According to Johann Kohl, who knew Buffalo, the chief’s conversion wasn’t based on politics or any kind of belief that Ojibwe culture and religion was inferior. Buffalo converted because he wanted to be united with his family in death. This may make the conversion less significant from a historical perspective, but it helps us understand the man himself. For that reason, this is the most important document yet about the end of the great chief’s long life.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892. Print.

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings round Lake Superior. London: Chapman and Hall, 1860. Print.

Loew, Patty. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2001. Print.

McElroy, Crocket. “An Indian Payment.” Americana v.5. American Historical Company, American Historical Society, National Americana Society Publishing Society of New York, 1910 (Digitized by Google Books) pages 298-302.

Morse, Richard F. “The Chippewas of Lake Superior.” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Ed. Lyman C. Draper. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1857. 338-69. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, 1991. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe, and Seth Eastman. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Collected and Prepared under the Direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs per Act of Congress of March 3rd, 1847. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo, 1851. Print.

Wagner, Moritz, and Karl Von Scherzer. Reisen in Nordamerika in Den Jahren 1852 Und 1853. Leipzig: Arnold, 1854. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: The Armstrong Engraving

October 3, 2013

This post is one of several that seek to determine how many images exist of Great Buffalo, the famous La Pointe Ojibwe chief who died in 1855. To learn why this is necessary, please read this post introducing the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search.

In 1892, thirty-seven years after the death of the La Pointe Chief Buffalo, a curious book appeared on the market. It was printed by A.W, Bowron of Ashland, Wisconsin, just south of Madeline Island at the end of Chequamegon Bay. It was titled Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences From the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong. More than any other book, this work has informed the public about the life of Buffalo, and it contains the only complete account of his famous 1852 journey to Washington D.C.

Benjamin Armstrong was born in Alabama. As a young man, he travelled throughout the South and up the Mississippi River eventually making it to Wisconsin. He learned Ojibwe, settled on Madeline Island, and married one of Buffalo’s nieces. Over time, he became Buffalo’s personal interpreter and accompanied him to Washington. His work translating the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe, which established reservations in Wisconsin on largely favorable terms to the Ojibwe, led Buffalo to refer to him as an adopted son. The chief even inserted a provision for a section of land for Armstrong within the ceded territory. The land Armstrong chose was at the site where downtown Duluth would rise.

Over the next several decades, Armstrong battled poverty, temporary blindness, and alcohol. He was duped into trading away his claim on Duluth and lost his bid to regain it in the U.S. Supreme Court. Had he hung on to the land, it would have made him very wealthy, but instead, he remained poor in the Chequamegon region. As he neared the end of his life, he decided to team with Thomas P. Wentworth of Ashland to record his memoirs. The work was completed in 1891 and went to press the following year.

Early Life Among the Indians is a complex work. Much of it contains rich details that could only have come from the true experiences of an insider. Other parts appear to be wholly fabricated. Armstrong’s tone is more that of a northwoods storyteller than it is of a academic historian. Faced with this dilemma, modern scholars of Ojibwe history have either fully embraced Armstrong or have completely rejected him. For the purposes of this study, we cannot do either.

Some of the images in Armstrong’s memior seem to have been created especially for the work and were not derived from earlier photographs (Marr and Richards Co.).

In the first two chapters, Armstrong describes the trip to Washington. He mentions himself, Buffalo, and the young orator Oshogay, making the trip along with four other Ojibwe men. From other sources, we know that a young mixed-blood from La Pointe, Vincent Roy Jr., was also part of the delegation. Within these two chapters, there are two images. Each may contain a representation of Buffalo.

All of the images in the book are from engravings produced by the Marr and Richards Engraving Company of Milwaukee. Born and trained in Germany, master engraver John Marr had started the company with the American-born George Richards in 1888. Their highly-precise maps, and illustrations appeared throughout the upper Midwest during this time period. For Early Life Among the Indians, it appears that Marr and Richards produced two types of engravings. One type was derived from original photographs, and the others were original designs to illustrate incidents from Armstrong’s stories. Of the latter type, a plate between pages 32 and 33 shows an image of five Indians huddled around a fire during a fierce thunderstorm. A bearded figure in a raincoat, presumably Armstrong, stands in the background.

This image, called Encountered on the Tpip [sic] to Washington., illustrates a part of Armstrong’s story where the delegation had to pull their canoe out of the water during a storm on the south shore of Lake Superior on the first leg of the journey. Of the five Ojibwe men shown, the one with the most feathers, nearest the viewer with his back and profile visible is the most prominent. However, all five are simple renderings that play into Indian stereotypes of the day and do not appear to be based on any real images. So, while the illustrators may have intended one to show Buffalo, this image was produced long after his death and does nothing to suggest what he would have looked like.

Washington Delegation, June 22, 1852: Chief Buffalo led this famous Ojibwe delegation to Washington, so it is assumed he is one of the men in this engraving, but which one? The original photograph has not been located (Marr and Richards Co.).

The image labelled Washington Delegation, June 22,1852, between pages 16 and 17, is much more intriguing. It shows three seated men in front of three standing men. The man standing on the right appears to be Armstrong, but the rest of them are not identified. There has been a lot of speculation whether or not this image shows Chief Buffalo. The man seated in the middle with the large white sash across his chest was featured on on poster of Buffalo released by the Minnesota Historical Society in the 1980s. He does appear to be the oldest and most prominent of the group. However, the man holding a pipe sitting to his left (bottom right in the picture)was used as the model for the large outdoor mural of Buffalo on the corner of Highways 2 and 13 in Ashland.

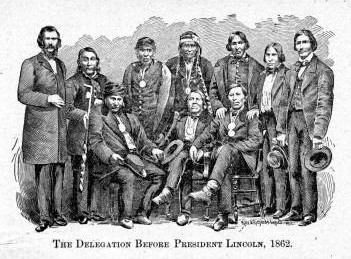

Besides the title and the engraver’s mark, there is no other information to identify the origin of this image. It almost certainly came from a photograph. Two similar engravings, found elsewhere in the book can be traced to specific photos. One Armstrong identifies as being the 1862 Ojibwe delegation to President Lincoln. In the engraving, seven chiefs stand behind three who sit. Again, the men are not identified, but Armstrong lists the names of the chiefs who accompanied him on pages 66 and 67. The Fond du Lac chief, Naaganab (Sits in Front) is identifiable from other photographs. As his name would suggest, he is seated in front in the center.

The photograph this engraving was made from was taken by the famous Civil War photographer Matthew Brady, and it can be found in the collections of the Minnesota Historical Society. From the postures and facial expressions of the men, it is clear the engraving was made from this photo. However, the two images are not exact duplicates. The man standing third from the left in the photo appears to have been moved to the far right in the engraving, and to the right of him, we see another man who is not in the photo. Because the photograph from MHS cuts off immediately to the right of the man who is third from the right in the engraving, it is impossible to know whether or not anyone stood there when the photo was taken.

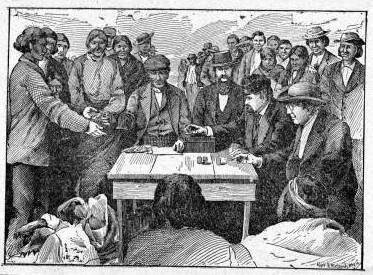

The other engraving based on a photograph appears between pages 134 and 135. Armstrong identifies it as Annuity papement [sic] at La Pointe, 1852. The photograph it comes from, by Charles Zimmerman, is well known to scholars of this time period, and it appears in many secondary works. One copy is held by the Wisconsin Historical Society. It shows four government officials from La Pointe seated at a table surrounded by Ojibwe men and women waiting to receive their treaty payments. Sources vary on the date. The Historical Society identifies it as 1870 and describes it as “Indians receiving payment. Seated on the right is John W. Bell. Others are, left to right, Asaph Whittlesey, Agent Henry C. Gilbert, and William S. Warren (son of Truman Warren).”

While the engraving of the 1852 Delegation is clearly also from a photograph, the original has not been located. If it exists, and contains any more identifying information, it represents possibly the best opportunity to see what Buffalo looked like. We need to find the photo!

The Verdict