Wheeler Papers: 1854 La Pointe before the Treaty

August 7, 2017

By Amorin Mello

Selected letters from the

Wheeler Family Papers,

Box 3, Folders 11-12; La Pointe County.

Crow-wing, Min. Ter.

Jan. 9th 1854

Brother Wheeler,

Reverend Leonard Hemenway Wheeler ~ In Unnamed Wisconsin by Silas Chapman, 1895, cover image.

Though not indebted to you just now on the score of correspondence, I will venture to intrude upon you a few lines more. I will begin by saying we are all tolerably well. But we are somewhat uncomfortable in some respects. Our families are more subject to colds this winter than usual. This probably may be attributed in part at least to our cold and open houses. We were unable last fall to do any thing more than fix ourselves temporarily, and the frosts of winter find a great many large holes to creep in at. Some days it is almost impossible for us to keep warm enough to be comfortable.

Our prospects for accomplishing much for the Indians here I do not think look more promising than they did last fall. There are but few Indians here. These get drunk every time they can get whiskey, of which there is an abundance nearby. Among the white people here, none are disposed to attend meetings much except Mr. [Welton?]. He and his wife are discontented and unhappy here, and will probably get away as soon as they can. We hear not a word from the Indian Department. Why they are minding us in this manner I cannot tell. But I should like it much better, if they would tell us at once to be gone. I have got enough of trying to do anything for Indians in connection with the Government. We can put no dependence upon any thing they will do. I have tried the experiment till I am satisfied. I think much more could be done with a boarding school in the neighborhood of Lapointe than here And my opinion is, that since things have turned out as they have here, we had better get out of it as soon as we can. With such an agent as we now have, nothing will prosper here. He is enough to poison everything, and will do more moral evil in such a community, as this, than a half a dozen missionaries can do good. My opinion is, that if they knew at Washington how things are and have been managed here, there would be a change. But I do not feel certain of this. For I sometimes am tempted to adopt the opinion that they do not care much there how things go here. But should there be a change, I have little hope that is would would make things materially better. The moral and social improvement of the Indians, I fear, has little to do with the appointment of agents and superintendents. I do not think I ought to remain here very long and keep my family here, as things are now going. If we were not involved with the Government with regard to the school matter, I would advise the Committee to quit here as soon as we can find a place to go to. My health is not very good. The scenes, and labors and attacks of sickness which I have passed through during the past two years have made almost a wreck of my constitution. It might rally under some circumstances. But I do not think it will while I stay here, so excluded from society, and so harassed with cares and perplexities as I have been and as I am likely to be in future, should we go on and try to get up a school. My wife is in no better spirits than I am. She has had several quite ill turns this winter. the children all wish to get away from here, and I do not know that I shall have power to keep them here, even if I am to stay.

But what to do I do not know. The Committee say they do not wish to abandon the Ojibwas. I cannot in future favor the removal of the lake Indians. I believe that all the aid they will receive from the Government will never civilize or materially benifit them. I judge from the manner in which things have been managed here. Our best hope is to do what we can to aid them where they are to live peaceably with the whites, and to improve and become citizens. The idea of the Government sending infidels and heathens here to civilize and Christianize the Indians is rediculous.

I always thought it doubtful whether the experiment we are trying would succeed. In that case it was my intention to remove somewhere below here, and try to get a living, either by raising my potatoes or by trying to preach to white people, or by uniting both. but I do not hardly feel strong enough to begin entirely anew in the wilderness to make me a home. I suppose my family would be as happy at Lapointe, as they would any where in the new and scattered settlements for fifty or a hundred miles below here. And if thought I could support myself then, I might think of going back there. There are our old friends for whose improvement we have laborred so many years. I feel almost as much attachment for them as for my won children. And I do not think they ought to be left like sheep upon the mountains without a shepherd. And if the Board think it best to expend money and labor for the Ojibwas, they had better expend it there than here, as things now are at least. I think we were exerting much much more influence there before we left, then we have here or are likely to exert. I have no idea that the lake Indians will ever remove to this place, or to this region.

Reverend Sherman Hall

~ Madeline Island Museum

What do you think of recommending to the Board to day to exert a greater influence on the people in the neighborhood of Lapointe[?/!] I feel reluctant to give up the Indians. And if I could get a living at Lapointe, and could get there, I should be almost disposed to go back and live among those few for whom I have labored so long, if things turn out here as I expect they will. I have not much funds to being life with now, nor much strength to dig with. But still I shall have to dig somewhere. The land is easier tilled in this region than that about the lake. But wood is more scarce. My family do not like Minesota. Perhaps they would, if they should get out of the Indian country. Edwin says he will get out of it in the spring, and Miles says he will not stay in such a lonesome place. I shall soon be alone as to help from my children. My boys must take care of themselves as soon as they arrive at a suitable age, and will leave me to take care of myself. We feel very unsettled. Our affairs here must assume a different aspect, or we cannot remain here many months longer. Is there enough to do at Lapointe; or is there a prospect that there will soon be business to draw people enough then, to make it an object to try to establish the institution of the gospel there? Write me and let me know your views on such subjects as these.

[Unsigned, but appears to be from Sherman Hall]

Crow-wing Feb. 10th 1854

Brother Wheeler:

I received your letter of jan. 16th yesterday, and consequently did not sleep as much as usual last night. We were glad to hear that you are all well and prosperous. We too are well which we consider a great blessing, as sickness in present situation would be attended with great inconvenience. Our house is exceedingly cold and has been uncomfortable during some of the severe cold weather have had during the last months. Yet we hope to get through the winter without suffering severely. In many respects our missionary spirit has been put to a severer test than at any previous time since we have been in the Indian country, during the past year. We feel very unsettled, and of course somewhat uneasy. The future does not look very bright. We cannot get a word from the Indian Department whether we may go on or not. If we cannot get some answer from them before long I shall be taking measures to retire. We have very little to hope, I apprehend, from all the aid the Government will render to words the civilization and moral and intellectual improvement of the Indians. For missionaries or Indians to depend on them, is to depend on a broken staff.

~ Minnesota Historical Society

“The American Fur Company therefore built a ‘New Fort’ a few miles farther north, still upon the west shore of the island, and to this place, the present village, the name La Pointe came to be transferred. Half-way between the ‘Old fort’ and the ‘New fort,’ Mr. Hall erected (probably in 1832) ‘a place for worship and teaching,’ which came to be the centre of Protestant missionary work in Chequamegon Bay.”

~ The Story of Chequamegon Bay

I do not see that our house is so divided against itself, that it is in any great danger of falling at present. My wife never did wish to leave Lapointe and we have ever, both of us, thought that the station ought not to be abandoned, unless the Indians were removed. But this seemed not to be the opinion of the committee or of our associates, if I rightly understood them. I had a hard struggle in my mind whether to retire wholly from the service of the Board among the Indians, or to come here and make a further experiment. I felt reluctant to leave them, till we had tried every experiment which held out any promise of success. When I remove my family here our way ahead looked much more clear than it does now. I had completed an arrangement for the school which had the approval of Gov. Ramsey, and which fell through only in consequence of a little informality on his part, and because a new set of officers just then coming into power must show themselves a little wiser than their predecessors. Had not any associates come through last summer, so as to relieve me of some of my burdens and afford some society and counsel in my perplexities I could not have sustained the burden upon me in the state of my health at that time. A change of officers here too made quite an unfavorable change in our prospects. I have nothing to reproach myself with in deciding to come here, nor in coming when we did, though the result of our coming may not be what we hoped it would be. I never anticipated any great pleasure in being connected with a school connected in any way with the Government, nor did I suppose I should be long connected with it, even if it prospered. I have made the effort and now if it all falls, I shall feel that Providence has not a work for us to do here. The prospects of the Indians look dark, what is before me in the future I do not know. My health is not good, though relief from some of the pressure I had to sustain for a time last fall and the cold season has somewhat [?????] me for the time being. But I cannot endure much excitement, and of course our present unsettled affairs operate unfavorably upon it. I need for a time to be where I can enjoy rest from everything exciting, and when I can have more society that I have here, and to be employed moderately in some regular business.

Antoine Gordon [Gaudin]

~ Noble Lives of a Noble Race by the St. Mary’s Industrial School (Bad River Indian Reservation), 1909, page 207.

Charles Henry Oakes

~ Findagrave.com

As to your account I have not had time to examine it, but will write you something about it by & by. As to any account which Antoine Gaudin has against me, I wish you would have him send it to me in detail before you pay it. I agreed with Mr. Nettleton to settle with him, and paid him the balance due to Antoine as I had the account. I suppose he made the settlement, when he was last at Lapointe. As to the property at Lapointe, I shall immediately write to Mr. Oakes about it. But I suppose in the present state of affairs, it will be perhaps, a long time before it will be settled so as to know who does own it. It is impossible for me to control it, but you had better keep posession of it at present. I cannot send Edwin [??] through to cultivate the land & take care of it. He will be of age in the spring, and if he were to go there I must hire him. He will probably leave us in the spring. Please give my best regards to all. Write me often.

Yours truly

S. Hall

Crow-wing, Min. Ter.

Feb. 21st 1854

Brother Wheeler,

Paul Hudon Beaulieu

~ FamilySearch.org

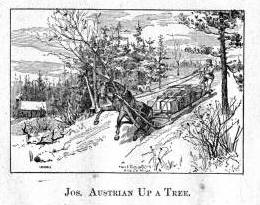

I wrote you a few days ago, and at the same time I wrote to Mr. Oakes inquiring whether he had got possession of the Lapointe property. I have not yet got a reply from him, but Mr. Beaulieu tells me that he heard the same report which you mentioned in your letter, and that he inquired of Mr. Oakes about it when he saw him on a recent visit to St. Paul, and finds that it is all a humbug. Oakes has nothing to do with it. Mr. Beaulieu said that the sale of last spring has been confirmed, and that Austrian will hold Lapointe. So farewell to all the inhabitants’ claims then, and to anything being done for the prosperity of the peace for the present, unless it gets out of his hands.

I have written to Austrian to try to get something for our property if we can. But I fear there is not much hope. If he goes back to Lapointe in the spring, do the best you can to make him give us something. I feel sorry for the inhabitants there that they are left at his mercy. He may treat them fairly, but it is hardly to be expected.

Clement Hudon Beaulieu

~ TreatiesMatter.org

As to our affairs here, there has been no particular change in their aspects since I wrote a few days ago. There must be a crisis, I think, in a few weeks. We must either go on or break up, I think, in the spring. We are trying to get a decision. I understand our agent has been threatened with removal if he carries on as he has done. I believe there is no hope of reformation in his case, and we may get rid of him. Perhaps God sent us here to have some influence in some such matters, so intimately connected with the welfare of the Indians. I have never thought I [????] can before I was sent in deciding to come here. Some trials and disappointments have grown out of my coming, but I feel conscious of having acted in accordance with my convictions of duty at this time.

If all falls through, I know not what to do in the future. The Home Missionary Society have got more on their hands now than they have funds to pay, if I were disposed to offer myself to labor under them. I may be obliged to build me a shanty somewhere on some little unoccupied piece of land and try to dig out a living. In these matters the Lord will direct by his providence.

You must be on your guard or some body will trip you up and get away your place. There are enough unprincipled fellows who would take all your improvements and send you and all the Indians into the Lake if they could make a dollar by it. I should not enlarge much, without getting a legal claim to the land. Neither would I advise you to carry on more family than is necessary to keep what team you must have, and to supply your family with milk and vegetables. It will be advantage/disadvantage to you in a pecuniary point of view, it will load you with and tend to make you worldly minded, and give your establishment the air of secularity in the eyes of the world. If I were to go back again to my old field, I would make my establishment as small as I could & have enough to live comfortable. I with others have thought that your tendency was rather towards going to largely into farming. I do not say these things because I wish to dictate or meddle with your affairs. Comparing views sometimes leads to new investigations in regard to duty.

May the Lord bless you and yours, and give you success and abundant prosperity in your labours of love and efforts to Save the Souls around you.

Give my best regards to Mrs. W., the children, Miss S and all.

Yours truly,

S. Hall

I forgot to say that we are all well. Henry and his family have enjoyed better health here, then they used to enjoy at Lapointe.

Feb 27

Brother Wheeler.

My delay to answer your note may require an explanation. I have not had time at command to attend to it conveniently at an earlier period. As to your first questions. I suppose there will be no difference of opinion between us as to the correctness of the following remarks.

- The Gospel requires the members of a church to exercise a spirit of love, meekness and forbearance towards an offending brother. They are not to use unnecessary severity in calling him to account for his errors. Ga. 6:1.

- The Object of Church discipline is, not only to [pursue/preserve?] the Church pure in doctrine & morals, that the contrary part may have no evil thing to say of them; but also to bring the offender to a right State of mind, with regard this offense, and gain him back to duty and fidelity.

- If prejudice exist in the mind of the offender towards his brethren for any reason, the spirit of the gospel requires that he be so approached if possible as to allay that prejudice, otherwise we can hardly expect to gain a candid hearing with him.

Charles William Wulff Borup, M.D. ~ Minnesota Historical Society

I consider that these remarks have some bearing on the case before us. If it was our object to gain over Dr. B. to our views of the Sabbath, and bring him to a right State of mind with regard this Sabbath breaking, the manner of approaching him would have, in my view, much to do with the offence. He may be approached in a Kind and [forbearing?] manner, when one of sternness and dictation will only repel him from you. I think we ought, if possible, and do our duty, avoid a personal quarrel with him. To have brought the subject before the Church & made a public affair of it, before [this/then?] and more private means have been tried to get satisfaction, would, I am sure, have resulted in this. I found from my own interviews with him, that there was hope, if the rest of the brethren would pursue a similar course. I felt pretty sure they would obtain satisfaction. IF they had [commenced?] by a public prosecution before the church, it would only have made trouble without doing any good. The peace of our whole community would have been disturbed. I thought one step was gained when I conversed with him, and another when you met him on the subject. I knew also that prejudices existed both in his mind towards us, & in our minds towards him which were likely to affect the settlement of this affair, and which as I thought, would be much allayed by individuals going to him and speaking face to face on this subject in private. He evidently expected they would do so. Mutual conversations and explanations allay these feelings very much. At least it has been so in my experience.

As to your second question. I do not say that it was Mr. Ely’s duty to open the subject to Doc. Borup at the preparatory lecture. If he had done so, it would have been only a private interview; for there [was?] not enough present to transact business. All I meant to affirm respecting that occasion is, that it afforded a good opportunity to do so, if he wishes, and that Dr. B. expected he would have done so, as I afterwards learnt, if he has any objection to make against his coming to the communion.

As to your third question. I have no complaint to make of the church, that I have urged them to the performance of any “duties“ in this case they have refused to perform.

And now permit me to ask in my turn.

What “duties” have they urged me to perform in this case, which I “have been unwilling, or manifested a reluctance to perform?”

Did you intend by anything which wrote to me or said verbally, to request me to commence a public prosecution of Doc. Borup before the Church?

Will you have the goodness to state in writing, the substance of what you said to me in your study as to your opinion and that of others suspecting my delinquency in maintaining church discipline.

A reply to these questions would be gratefully received.

Your brother in Christ

S. Hall

Crow Wing. March 12th 1854

Brother Wheeler:

Your letter of Feb 17th came to hand by our last mail; and though I wrote you but a short time ago, I will say a few words in relation to one or two topics to which you allude. Shortly after I received your former letter I wrote to Mr. Oakes enquiring about the property at Lapointe. In reply, says that himself and some others purchased Mr. Austrian’s rights at Lapointe of Old Hughes on the strength of a power of attorney which he held. Austrian asserts the power of attorney to be fraudulent, and that they cannot hold the property. Oakes writes as if he did not expect to hold it. Some time ago I wrote to Mr. Austrian on the same subject, and said to him that if I could get our old place back, I might go back to Lapointe. He says in reply —

Julius Austrian

~ Madeline Island Museum

“I should feel much gratified to see you back at Lapointe again, and can hold out to you the same inducements and assurances as I have done to all other inhabitants, that is, I shall be at Lapointe early in the spring and will have my land surveyed and laid out into lots, and then I shall be ready to give to every one a deed for the lot he inhabits, at a reasonable price, not paying me a great deal more than cost trouble, and time. But with you, my dear Sir, will be no trouble, as I have always known you a just and upright man, and have provided ways to be kind towards us, therefore take my assurance that I will congratulate myself to see you back again; and it shall not be my fault if you do not come. If you come to Lapointe, at our personal interview, we will arrange the matter no doubt satisfactory.”

“The property” from the James Hughes Affair is outlined in red. This encompassed the Church at La Pointe (New Fort) and the Mission (Middleport) of Madeline Island. 1852 PLSS survey map by General Land Office.

I suppose Austrian will hold the property and probably we shall never realize anything for our improvements. You must do the best you can. Make your appeal to his honor, if he has any. It will avail nothing to reproach him with his dishonesty. I do not know what more I can do to save anything, or for any others whose property is in like circumstances with ours.

You speak discouragingly of my going back to Lapointe. I do not think the Home Miss. Soc. would send a missionary there only for the few he could reach in the English language. If the people want a Methodist, encourage them to get one. It is painful to me to see the place abandoned to irreligion and vices of every Kind, and the labours I have expended there thrown away. I can hardly feel that it was right to give up the station when we did. If I thought I could support myself there by working one half the time and devoting the rest to ministerial labors for the good of those I still love there, I should still be willing to go back, if could get there & had a shelter for my head, unless there is a prospect of being more useful here. But the land at Lapointe is so hard to subdue that I am discouraged about making an attempt to get a living there by farming. I am not much of a fisherman. There is some prospect that we may be allowed to go on here. Mr. Treat has been to Washington, and says he expects soon to get a decision from the Department. We have got our school farm plowed, and the materials are drawn out of the woods for fencing it. If I have no orders to the contrary, I intend to go on & plant a part of it, enough to raise some potatoes. We may yet get our school established. If we can go ahead, I shall remain here, but if not, I think it is not my duty to remain here another year, as I have the past. In other circumstances, I could do more towards supporting myself and do more good probably.

I have felt much concerned for the people of Lapointe and Bad River on account of the small pox. May the Lord stay this calamity from spreading among you. Write us every mail and tell us all. It is now posted here today that the Old Chief [Kibishkinzhugon?] is dead. I hardly credit the report, though I should suppose he might be one of the first victims of the disease.

I can write no more now. We are all very well now. Give my love to all your family and all others.

Tell Robert how the matters stands about the land. It stands him in how to be on good terms with the Jew just now.

Yours truly,

S. Hall

The snow is nearly all off the ground and the weather for two or three weeks has been as mild as April.

Crow Wing M.H. Apr. 1 1854

Dear Br. & Sr. Wheeler.

I have received a letter from you since I wrote to you & am therfore in your debt in that matter. I have also read your letters to Br. & Sr. Welton I suppose you have received my letter of the 13th of Feb. if so, you have some idea of our situation & I need say no more of that now; & will only say that we are all well as usual & have been during the winter. Mrs. P_ is considerably troubled with her old spinal difficulty. She has got over her labors here last summer * fall. Harriet is not well I fear never will be, because the necessary means are not likely to be used, she has more or less pain in her back & side all the time, but she works on as usual & appears just as she did at LaPointe, if she could be freed from work so as to do no more than she could without injury & pursue uninterruptedly & proper medical course I think she might regain pretty good health. (Do not, any of you, send back these remarks it would not be pleasing to her or the family.) We have said what we think it best to say) –

Br. Hall is pretty well but by no means the vigorous man he once was. He has a slight – hacking cough which I suppose neither he nor his family have hardly noticed, but Mrs. P_ says she does not like the sound of it. His side troubles him some especially when he is a good deal confined at writing. Mr. & Mrs. W_ are in usual health. Henry’s family have gone to the bush. They are all quite well. He stays here to assist br. H_ in the revision & keeps one or two of his children with him. They are now in Hebrews, with the Revision. Henry I suppose still intends to return to Lapointe in the spring. –

Now, you ask, in br. Welton’s letter, “are you all going to break up there in the spring.” Not that I know of. It would seem to me like running away rather prematurely. When the question is settled, that we can do nothing here, then I am willing to leave, & it may be so decided, but it is not yet. We have not had a whisper from Govt. yet. Wherefore I cannot say.

It looks now as if we must stay this season if no longer. Dr. Borup writes to br. Hall to keep up good courage, that all will come out right by & by, that he is getting into favor with Gov. Gorman & will do all he can to help us. (Br. Hall’s custom is worth something you know).

Henry C. Gilbert

~ Branch County Photographs

By advise of the Agent, we got out (last month) tamarack rails enough to fence the school farm (which was broke last summer) of some 80 acres & it will be put up immediately. Our great father turned out the money to pay for the job. These things look some like our staying awhile I tell br H_ I think we had better go as far as we can, without incurring expense to the Board (except for our support) & thus show our readiness to do what we can. if we should quit here I do not know what will be done with us. Br Hall would expect to have the service of the Board I suppose. Should they wish us to return to Bad River we should not say nay. We were much pleased with what we have heard of your last fall’s payment & I am as much gratified with the report of Mr. H. C. Gilbert which I have read in the Annual Report of the Com. of Indian Affairs. He recommends that the Lake Superior Indians be included in his Agency, that they be allowed to remain where they are & their farmers, blacksmith & carpenter be restored to them. If they come under his influence you may expect to be aided in your efforts, not thwarted , by his influence. I rejoice with you in your brightening prospects, in your increased school (day & Sabbath) & the increased inclination to industry in those around you. May the lord add his blessing, not only upon the Indians but upon your own souls & your children, then will your prosperity be permanent & real. Do not despise the day of small things, nor overlook especially neglect your own children in any respect. Suffer them not to form idle habits, teach them to be self reliant, to help themselves & especially you, they can as well do it as not & better too, according to their ability & strength, not beyond it, to fear God & keep his commandments & to be kind to one another (Pardon me these words, I every day see the necessity of what I have said.) We sympathize with you in your situation being alone as you are, but remember you have one friend always near who waits to [commence?] with you, tell Him & all with you from Abby clear down to Freddy.

Affectionately yours

C. Pulsifer

Write when you can.

Crow wing Min. Ter.

April 3d 1854

Brother Wheeler

George E. Nettleton and his brother William Nettleton were pioneers, merchants, and land speculators at what is now Duluth and Superior.

~ Image from The Eye of the North-west: First Annual Report of the Statition of Superior, Wisconsin by Frank Abial Flower, 1890, page 75.

Since I wrote you a few days ago, I have received a letter from Mr. G. E. Nettleton, in which he says, that when he was at Lapointe in December last, he was very much hurried and did not make a full settlement with Antoine. He says further, that he showed him my account, and told him I had settled with him, and that he would see the matter right with Antoine. A. replied that all was right. I presume therefore all will be made satisfactory when Mr. N. comes up in the Spring, and that you will have need to make yourself no further trouble about this matter.

I have also received a short note from Mr. Treat in which he says,

“I have not replied to your letters, because I have been daily expecting something decisive from Washington. When I was there, I had the promise of immediate action; but I have not heard a word from them”.

“I go to Washington this Feb, once more. I shall endeavor to close up the whole business before I return. I intend to wait till I get a decision. I shall propose to the Department to give up the school, if they will indemnify us. If I can get only a part of what we lose, I shall probably quit the concern”.

Thus our business with the Government stood on March the 9th, I have lost all confidence in the Indian Department of our Government under this administration, to say nothing of the rest of it. If the way they have treated us is an index to their general management, I do not think they stand very high for moral honesty. The prospects for the Indians throughout all our territories look dark in the extreme. The measures of the Government in relation to them are not such as will benefit and save many of them. They are opening the floodgates of vice and destruction upon them in every quarter. The most solemn guarantees that they shall be let alone in the possession of domains expressly granted them mean nothing.

Our prospects here look dark. For some time past I have been rather anticipating that we should soon get loose and be able to go on. But all is thrown into the dark again. What I am to do in future to support my family, I do not know. If we are ordered to quit here and turn over the property, it would turn [illegible] out of doors.

Mr. Austrian expects us back to Lapointe in the Spring & Mr. Nettleton proposes to us to go to Fond du Lac, (at the Entry). He says there will be a large settlement then next season. A company is chartered to build a railroad through from the Southern boundary of this territory to that place. It is probable that Company [illegible] will make a grant of land for that purpose. If so, it will probably be done in a few years. That will open the lake region effectually. I feel the need of relaxation and rest before I do anything to get established anywhere.

We are still working away at the Testament, it is hard work, and we make lately but slow progress. There is a prospect that the Bible Society will publish it but it is not fully decided. I wish I could be so situated that I could finish the grammar.

But I suppose I am repeating what I have said more than once before. We are generally in good health and spirits. We hope to hear from by next mail.

Yours truly

S. Hall

What do you think about the settlements above Lapointe and above the head of the Lake?

Detroit July 10th 1854

Rev. Dr. Bro.

At your request and in fulfilment of my promise made at LaPointe last fall so after so long a time I write: And besides “to do good & to communicate” as saith the Apostle “forget not, for with such sacrifices God is well pleased.”

We did not close up our Indian payments of last year until the middle of the following January, the labors, exposures and excitements of which proved too much for me and I went home to New York sick & nearly used up about the last of February & continued so for two months. I returned here about a week ago & am now preparing for the fall pay’ts.

The Com’sr. has sent in the usual amounts of Goods for the LaPointe Indians to Mr. Gilbert & I presume means to require him to make the payment at La P. that he did last fall, although we have received nothing from the Dep’t. on the subject.

“George Washington Manypenny (1808-1892) was the Director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs of the United States from 1853 to 1857.”

~ Wikipedia.org

In regard to the Treaty with the Chipp’s of La Sup’r & the Miss’i, the subject is still before Congress and if one is made this fall it has been more than intimated that Com’r Manypenny will make it himself, either at LaP’ or at F. Dodge or perhaps at some place farther west. Of course I do not speak from authority or any of the points mentioned above, for all is rumour & inference beyond the mere arrival here of the Goods to Mr G’s care.

From various sources I learn that you have passed a severe winter and that much sickness has been among the Indians and that many of them have been taken away by the Small Pox.

This is sad and painful intelligence enough and I can but pray God to bless & overrule all to the goods of his creasures and especially to the Missionaries & their families.

Notwithstanding I have not written before be assured that I have often [???] of and prayed for you and yours and while in [Penn.?] you made your case my own so far as to represent it to several of our Christian brethren and the friends of missions there and who being actuated by the benevolent principles of the Gospel, have sent you some substanted relief and they promise to do more.

The Elements of the political world both here and over the waters seem to be in fearful & [?????] commotion and what will come of it all none but the high & holy one can know. The anti Slavery Excitement with us at the North and the Slavery excitement at the South is augmenting fact and we I doubt not will soon be called upon to choose between Slavery & freedom.

If I do not greatly misjudge the blessed cause of our holy religion is or seems to be on the wane. I trust I am mistaken, but the Spirit of averice, pride, sensuality & which every where prevails makes me think otherwise. The blessed Christ will reign [recenth-den?] and his kingdom will yet over all prevail; and so may it be.

Let us present to him daily the homage of a devout & grateful heart for his tender mercies [tousward?] and see to it that by his grace we endure unto the end that we may be saved.

My best regards to Mrs. W. to Miss Spooner to each of the dear children and to all the friends & natives to each of whom I desire to be remembered as opportunity occurs.

The good Lord willing I may see you again this fall. If I do not, nor never see you again in this world, I trust I shall see and meet you in that world of pure delight where saints immortal reign.

May God bless you & yours always & ever

I am your brother

In faith Hope & Charity

Rich. M. Smith

Rev Leonard H. Wheeler

LaPointe

Lake Superior

Miss. House Boston

Augt’ 31, 1854

Rev. L. H. Wheeler,

Lake Superior

Dear Brother

Yours of July 31 I laid before the Com’sr at our last meeting. They have formally authorized the transfer of Mr & Mrs Pulsifer to the Lake, & also that of Henry Blatchford.

Robert Stuart was formerly an American Fur Company agent and Acting Superintendent on Mackinac Island during the first Treaty at La Pointe in 1842.

~ Wikipedia.org

In regard to the “claims” their feeling is that if the Govt’ will give land to your station, they have nothing to say as to the quantity. But if they are to pay the usual govt’ price, the question requires a little caution. We are clear that we may authorize you to enter & [???] take up so much land as shall be necessary for the convenience of the [mission?] families; but we do not see how we can buy land for the Indians. Will you have the [fondness?] to [????] [????] on these points. How much land do you propose to take up in all? How much is necessary for the convenience of the mission families?

Perhaps you & others propose to take up the lands with private funds. With that we have nothing to do, so long as you, Mr P. & H. do not become land speculators; of which, I presume, there is no danger.

As to the La Pointe property, Mr Stuart wrote you some since, as you know already I doubt not, and replied adversely to making any bargain with Austrian. I took up the opinion of the Com’sr after receiving your letter of July 31, & they think it the wise course. I hope Mr Stewart will get this matter in some shape in due time.

I will write to him in reference to the Bad River land, asking him to see it once if the gov’ will do any thing.

Affectionate regards to Mrs W. & Miss Spooner & all.

Fraternally Yours

S. B. Treat

P.S. Your report of July 31 came safely to hand, as you will & have seen from the Herald.

By Leo Filipczak

Joseph Oesterreicher was only eighteen years old when he arrived at La Pointe in 1851. Less than a year earlier, he had left his native Germany for Mackinac, where he’d come to work for the firm of his older brother Julius and their in-laws, the Leopolds, another Bavarian Jewish family trading on Lake Superior.

In America, the Oesterreichers became the Austrians, but in his time at Mackinac, Joseph Austrian picked up very little English and even less of the Ojibwe and Metis-French that predominated at La Pointe. So, when Joseph made the move to his brother’s store at Madeline Island, it probably felt like he was immigrating all over again.

In the spring of 1851, he would have found at La Pointe, a society in flux. American settlement intensified as the fur trade economy made its last gasps. The island’s mix-blooded voyageurs found it harder and harder to make a living, and the Fur Company, and smaller traders like Julius Austrian, began to focus more on getting Ojibwe money from treaty annuity payments than they did from the actual trade in fur. This competition for Indian money had led to the deaths of hundreds of Ojibwe people in the Sandy Lake tragedy just a few months earlier.

The uncertainty surrounding Ojibwe removal would continue to hang heavily over the Island for both of Joseph’s years at La Pointe, as the Ojibwe leadership scrambled to process the horror of Sandy Lake and tried to secure a permanent homeland on the lakeshore.

The Austrians, however, found this an opportune time to be at the forefront of all the new business ventures in the Lake Superior country. They made money in merchandise, real estate, shipping, mining, lumber, government contracts, and every other way they could. This was not without controversy, and the name of Julius Austrian is frequently attached to documents showing the web of corruption and exploitation of Native people that characterized this era.

It’s difficult to say whether Joseph realized in 1851, while sweeping out his brother’s store or earning his unfortunate nickname, but he would become a very wealthy man. He lived into the 20th century and left a long and colorful memoir. I plan to transcribe and post all the stories from pages 26-66, which consists of Joseph’s time at La Pointe. Here is the first fourth [our original] installment:

Memoirs of Doodooshaboo

… continued from Mackinac 1850-1851.

Left for La Point: My First Trip on Lake Superior

1851

Julius Austrian

~ Madeline Island Museum

Mr. Julius Austrian was stationed at La Pointe, Madaline Island, one of the Apostle Group in Lake Superior, where he conducted an Indian Trading post, buying large quantities of fur and trading in fish on the premises previously occupied by the American Fur Co. whose stores, boats etc. the firm bought.

Julius Austrian, one of the partners had had charge of the store at La Point for five years past, he was at this time expected at Mackinaw and it had been arranged that I should accompany him back to La Pointe when he returned there, on the first boat of the season leaving the Sault Ste. Marie. I was to work in the store and to assist generally in all I was capable of at the wages of $10 a month. I gladly accepted the proposition being anxious for steady employment. Shortly after, brother Julius, his wife (a sister of H. Leopold) and I started on the side wheel steamer Columbia for Sault Ste. Marie, generally called “The Soo,” and waited there five days until the Napoleon, a small propellor on which we intended going to La Point, was ready to sail. During this time she was loading her cargo which had all to be transported from the Soo River to a point above the rapids across the Portage (a strip of land about ¾ of a mile connecting the two points) on a train road operated with horses. At this time there were only two propellers and three schooners on the entire Lake Superior, and those were hauled out below the rapids and moved up and over the portage and launched in Lake Superior. Another propeller Monticello, which was about half way across the Portage, was soon to be added to the Lake Superior fleet, which consisted of Independence & Napoleon and the Schooners Algonquin, Swallow, and Sloop Agate owned by my brother Julius. Quite different from the present day, where a very large number of steel ships on the chain of Lakes, some as much as 8000 tons capacity, navigate through the canal to Lake Superior from the lower lakes engaged in transporting copper, iron ore, pig iron, grain & flour from the various ports of Marquette, Houghton, Hancock, Duluth, and others. It was found necessary in later years to enlarge the locks of the canal to accomodate the larger sized vessels that had been constructed.

Building Sault Ste. Marie Canal. 1851.

Map of proposed Soo canal and locks 1852 (From The Honorable Peter White by Ralph D. Williams, 1910 pg. 121)

The ship canal at that time had not been constructed, but the digging of it had just been started. The construction of this canal employed hundreds of laborers, and it took years to complete this great piece of work, which had to be cut mostly through the solid rock. The State of Michigan appropriated thousands of sections of land for the purpose of building this canal, for the construction of which a company was incorporated under the name of Sault Ste. Marie Ship Canal & Land Co., who received the land in payment for building this canal, and which appropriation entitled the Co. to located in any unsold government land in the State of Michigan. The company availed itself of this privilege and selected large tracts of the best mineral and timber land in Houghton, Ontonagan & Kewanaw Counties, locating some of the land in the copper district, some of which proved afterwards of immense value, and on which were opened up some of the richest copper mines in the world, namely: Calumet, Hecla, and Quincy mines, and others. There were also very valuable timber lands covered by this grant.

The canal improved and enlarged as it now stands, is one of the greatest and most important artificial waterways in the world. A greater tonnage is transported through it annually that through the Suez or any other canal. In later years the canal was turned over by the State of Mich. to the General Government, which made it free of toll to all vessels and cargoes passing through it, even giving Canadian vessels the same privilege; whereas when operated by the State of Mich. toll was exacted from all vessels and cargoes using it.

The Napoleon, sailed by Capt. Ryder, had originally been a schooner, it had been turned into a propeller by putting in a small propeller engine. She had the great (?) speed of 8 miles an hour in calm weather, and had the reputation of beating any boat of the Lake in rolling in rough weather, and some even said she had rolled completely over turning right side up finally.

To return to my trip, after passing White Fish Point, the following day and getting into the open lake, we encountered a strong north wind raising considerable sea, causing our boat to toss and pitch, giving us our first experience of sea sickness on the trip. Beside the ordinary crew, we had aboard 25 horses for Ontonogan where we arrived the third day out. The Captain finding the depth of water was not sufficient to allow the boat to go inside the Ontonogan river and there being no dock outside, he attempted to land the horses by throwing them overboard, expecting them to swim ashore, to begin with, he had three thrown overboard and had himself with a few of his men lowered in the yawl boat to follow, he caught the halter of the foremost horse intending to guide him and the others ashore. The lake was exceedingly rough, and the poor horses became panic stricken and when near the shore turned back swimming toward the boat with hard work. The Captain finally succeeded in land those that had been thrown overboard, but finding it both hazardous to the horses and the men he concluded to give up the attempt to land the other horses in this way, and ordered the life boat hoisted up aboard. She had to be hoisted up the stern, in doing so a heavy wave struck and knocked it against the stern of the boat before she was clear of the water with such force as to endanger the lives of the Capt. and men in it, and some of the passengers were called on to assist in helping to hoist the life boat owing to its perilous position. Captain and the men were drenched to the skin, when they reached the deck. Capt. vented his rage in swearing at the hard luck and was so enraged that he did not change his wet clothing for some time afterward. The remaining horses were kept aboard to be delivered on the return trip, and the boat started for her point of destination La Point.

Arrived at La Point and Started in Employ of Brother Julius. 1851

Next morning we sighted land, which proved to be the outer island of the Apostle Group. Captain flew into the wheel room and found the wheelsman fast asleep. He grasped the wheel and steered the boat clear of the rocks, just in time to prevent the boat from striking. Captain lost no time in changing wheelsman. We arrived without further incidents at La Point the same afternoon. When she unloaded her cargo, work was at once begun transferring goods to the store, in which I assisted and thus began my regular business career. These goods were hauled to the store from the dock in a car, drawn by a horse, on wooden rails.

There were only about 6 white American inhabitants on the Island, about 50 Canadian Frenchmen who were married to squaws, and a number of full blooded Indians, among whom was chief Buffalo who was a descendant of chiefs & who was a good Indian and favorably regarded by the people.

Fr. Otto Skolla (self-portrait contained in History of the diocese of Sault Ste, Marie and Marquette (1906) by Antoine Ivan Rezek; pg.360; Digitized by Google Books)

The most conspicuous building in the place was an old Catholic Church which had been created more than 50 years before by some Austrian missionaries. This church contained some very fine and valuable paintings by old masters. The priest in charge there was Father Skolla, an Austrian, who himself was quite an artist, and spent his leisure hours in painting Holy pictures. The contributions to the church amounted to a mere pittance, and his consequent poverty allowed him the most meager and scant living. One Christmas he could not secure any candles to light up his church which made him feel very sad, my sister-in-law heard of this and sent me with a box of candles to him, which made him the happiest of mortals. When I handed them to him, his words were inadequate to express his gratitude and praise for my brother’s wife.

There was also a Methodist church of which a man by the name of Hall was the preacher. He had several sons and his family and my brother Julius and his wife were on friendly terms and often met.

The principle man of the place was Squire Bell, a very genial gentleman who held most of the offices of the town & county, such as Justice of the Peace & Supervisor. He also was married to a squaw. This was the fashion of that time, there being no other women there.

John W. Bell, “King of the Apostle Islands” as described by Benjamin Armstrong (Digitized by Google Books) .

John W. Bell, “King of the Apostle Islands” as described by Benjamin Armstrong (Digitized by Google Books) .There was a school in the place for the Indians and half breeds, there being no white children there at this time. I took lessons privately of the teacher of this school, his name was Pulsevor. I was anxious to perfect myself in English. I also picked up quite a bit of the Chippewa language and in very short time was able to understand enough to enable me to trade with the Indians.

My brother Julius was a very kind hearted man, of a very sympathetic and indulgent nature, and to his own detriment and loss he often trusted needy and hungry Indians for provisions and goods depending on their promise to return the following year with fur in payment for the goods. He was personally much liked and popular with the Indians, but his business with them was not a success as the fur often failed to materialize. The first morning after my arrival, my brother Julius handed me a milk pail and told me to go to the squaws next door, who having a cow, supplied the family with the article. He told me to ask for “Toto-Shapo” meaning in the Indian language, milk.

I repeated this to myself over and over again, and when I asked the squaw for “Toto Shapo” she and all the squaws screamed with delight and excitement to think that I had just arrived and could make myself understood in the Indian tongue. This fact was spread among the Indians generally and from that day on while I remained on the Island I was called “Toto Shapo.” One of the Indian characteristics is to name people and things by their first impression–for instance on seeing the first priest who work a black gown, they called him “Makada-Conyeh,” which means a black gown, and that is the only name retained in their language for priests. The first soldier who had a sword hanging by his side they called “Kitchie Mogaman” meaning “a big knife” in their language. The first steamboat they saw struck them as a house with fire escaping through the chimney, consequently they called it “Ushkutua wigwam” (Firehouse) which is also the only name in their language for steamboat. Whiskey they call “Ushkutua wawa” meaning “Fire Water.”

My brother Julius had the United States mail contract between La Point & St. Croix. The mail bag had to be taken by a man afoot between these two places via Bayfield a distance of about 125 miles, 2 miles of these being across the frozen lake from the Island to Bayfield.

Dangerous Crossing on the Ice.

An Indian named Kitchie (big) Inini (man) was hired to carry it. Once on the way on he started to cross on the ice but found it very unsafe and turned back. When my brother heard this, he made up his mind to see that the mail started on its way across the Lake no matter what the consequence. He took a rope about 25 ft. long tying one end around his body and the other about mine, and he and I each took a long light pole carrying it with two hands crosswise, which was to hold us up with in case we broke through the ice. Taking the mail bag on a small tobogan sled drawn by a dog, we started out with the Indian. When we had gone but a short way the ice was so bad that the Indian now thoroughly frightened turned back again, but my brother called me telling me not to pay any attention to him and we went straight on. This put him to shame and he finally followed us. We reached the other side in safety, but had found the crossing so dangerous, that we hesitated to return over it and thought best to wait until we could return by a small boat, but the time for this was so uncertain that after all we concluded to risk going back on the ice taking a shorter cut for the Island, and we were lucky to get back all right.

In the summer when the mail carrier returned from these trips, he would build a fire on the shore of the bay about 5 miles distant, as a signal to send a boat to bring him across to the Island. Once I remember my brother Julius not being at home when a signal was given. I with two young Indian boys (about 12 yrs. of age) started to cross over with the boat, when about two miles out a terrific thunder and hail storm sprang up suddenly. The hail stones were so large that it caused the boys to relax their hold on the oars and it was all I could do to keep them at the oars. I attempted to steer the boat back to the Island, and barely managed to reach there. The boat was over half full of water when we reached the shore. When I landed we were met by the boys’ mothers who were greatly incensed at my taking their boys on this perilous trip, nearly resulting in drowning them. They didn’t consider I had no idea of this terrible thunder storm which so suddenly came up and had I known it for my own safety would not dreamed of attempting the trip.

Nearly Capsize in a Small Boat.

Once I went out in a small sail boat with two Frenchmen to collect some barrels of fish near the Island at the fishing ground near La Point. We got two barrels of fish which they stood up on end, when a sudden gust of wind caused the boat to list to one side so that the barrels fell over on the side and nearly capsized the boat. By pulling the barrels up the boat was finally righted after being pretty well filled with water. I could not swim, and as a matter of self-preservation grabbed the Frenchman nearest me. He was furious, expressing his anger half in French and half in English, saying, “If I had drowned, I would have taken him with me.” which no doubt was true.

A Young Indian Locked up for Robbery

One day brother Julius went to the Indian payment. During his absence I with another employee, Henry Schmitz, were left in charge. A young Indian that night burglarized the store stealing some gold coins from the cash drawer. The same were offered to someone in the town next day who told me, which led to his detection. He admitted theft and was committed to jail by the Indian agent Mr. Watrous, which the Indians consider a great disgrace.

Some inquisitive boys peering through the window discovered that the young Indian had attempted to commit suicide and spread the alarm. His father was away at the time and his mother and friends were frenzied and their threats of vengeance were loud. The jailer was found but he had lost the key to the jail (the jail was in a log hut) the door of which was finally forced open with an axe, and the young culprit with his head bleeding was handed over to his people who revived him in their wigwam. The next day the money was returned and we and the authorities were glad to call it quits.

To be continued at La Pointe 1851-1852 (Part 2)…

Special thanks to Amorin Mello and Joseph Skulan for sharing this document and their important research on the Austrian brothers and their associates with me. It is to their credit that these stories see the light of day. The original handwritten memoir of Joseph Austrian is held by the Chicago History Museum.

The Old Mission Church, La Pointe, Madeline Island. (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: 24827)

The Old Mission Church, La Pointe, Madeline Island. (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: 24827) Harriet Wheeler, pictured about forty years after receiving this letter. (Wisconsin Historical Society: Image ID 36771)

Harriet Wheeler, pictured about forty years after receiving this letter. (Wisconsin Historical Society: Image ID 36771) Many Ojibwe leaders, including Hole in the Day, blamed the rotten pork and moldy flour distributed at Sandy Lake for the disease that broke out. The speech in St. Paul is covered on pages 101-109 of Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader, my favorite book about this time period. (Photo from Whitney’s Gallery of St. Paul: Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID 27525)

Many Ojibwe leaders, including Hole in the Day, blamed the rotten pork and moldy flour distributed at Sandy Lake for the disease that broke out. The speech in St. Paul is covered on pages 101-109 of Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader, my favorite book about this time period. (Photo from Whitney’s Gallery of St. Paul: Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID 27525) Mary Warren (1835-1925), was a teenager at the time of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. She is pictured here over seventy years later. Mary, the sister of William Warren, had been living with the Wheelers but stayed with Hall during their trip east. (Photo found on

Mary Warren (1835-1925), was a teenager at the time of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. She is pictured here over seventy years later. Mary, the sister of William Warren, had been living with the Wheelers but stayed with Hall during their trip east. (Photo found on