By Leo

In April, the Supreme Court heard arguments in the case Department of Commerce v. New York and could render a decision any day on whether or not the 2020 federal census should include a question asking about citizenship status. In January, a Federal District Court in New York ruled that commerce secretary, Wilbur Ross, violated the law by pushing for that question.

Those in agreement with the District ruling suggest that the Trump administration wants to add the question as a way of discouraging immigrants from participating in the census, thereby diminishing the political power of immigrant communities. This, they say, would violate the Constitution on the grounds that the census must be an “actual enumeration” of all persons within the United States, not only citizens.

Proponents of the citizenship question counter that citizenship status is a perfectly natural question to ask in the census, that any government would want to know how many citizens it has, and that several past iterations of the 10-year count have included similar questions.

It remains to be seen how the Supreme Court will rule, but chances are it will not be the last time an issue of race, identity, or citizenship pops up in the politics of the census. From its creation by the Constitution as a way to apportion seats in congress according to populations of the states, the count has always begged tricky questions that essentially boil down to:

Who is a real American? Who isn’t? Who is a citizen? Who is three-fifths of a human being? Who might not be human at all? What does it mean to be White? To be Colored? To be civilized? How do you classify the myriad of human backgrounds, cultures and stories into finite, discrete “races?”

The Civil War and Fourteenth Amendment helped shed light on some of these questions, but it would be a mistake to think that they belong to the past. The NPR podcast Codeswitch has done an excellent series on census, and this episode from last August gives a broad overview of the history.

Here at Chequamegon History, though, we aren’t in the business broad overviews. We are going to drill down right into the data. We’ll comb through the 1850 federal census for La Pointe County and compare it with the 1860 data for La Pointe and Ashland Counties. Just for fun, we’ll compare both with the 1855 Wisconsin State Census for La Pointe County, then double back to the 1840 federal census for western St. Croix County. Ultimately, the hope is to help reveal how the population of the Chequamegon region viewed itself, and ultimately how that differed from mainstream America’s view. With luck, that will give us a framework for more stories like Amorin’s recent post on the killing of Louis Gurnoe.

Background

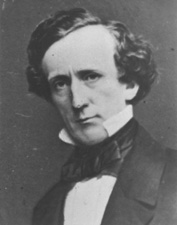

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his short memorial biography in the 1902 Proceedings of the State Bar Association.

Judge Daniel Harris Johnson of Prairie du Chien had no apparent connection to Lake Superior when he was appointed to travel northward to conduct the census for La Pointe County in 1850. The event made an impression on him. It gets a mention in his short memorial biography in the 1902 Proceedings of the State Bar Association.

Two years after statehood, Lake Superior’s connection to the rest of Wisconsin was hardly existent. This was long before Highways 51 and 53 were built, and commerce still flowed west to east. Any communication to or from Madison was likely to first go through Michigan via Mackinaw and Sault Ste. Marie, or through Minnesota Territory via St. Paul, Stillwater, and Sandy Lake. La Pointe County had been created in 1845, and when official business had to happen, a motley assortment of local residents who could read and write English: Charles Oakes, John W. Bell, Antoine Gordon, Alexis Carpentier, Julius Austrian, Leonard Wheeler, etc. would meet to conduct the business.

It is unclear how much notice the majority Ojibwe and French-patois speaking population took of this or of the census generally. To them, the familiar institutions of American power, the Fur Company and the Indian Agency, were falling apart at La Pointe and reorganizing in St. Paul with dire consequences for the people of Chequamegon. When Johnson arrived in September, the Ojibwe people of Wisconsin had already been ordered to remove to Sandy Lake in Minnesota Territory for their promised annual payments for the sale of their land. That fall, the government would completely botch the payment, and by February, hundreds of people in the Lake Superior Bands would be dead from starvation and disease.

So, Daniel Johnson probably found a great deal of distraction and anxiety among the people he was charged to count. Indians, thought of by the United States as uncivilized federal wards and citizens of their own nations, were typically not enumerated. However, as I wrote about in my last post, race and identity were complicated at La Pointe, and the American citizens of the Chequamegon region also had plenty to lose from the removal.

Madison, for its part, largely ignored this remote, northern constituency and praised the efforts to remove the Ojibwe from the state. It isn’t clear how much Johnson was paying attention to these larger politics, however. He had his own concerns:

House Documents, Volume 119, Part 1. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1859. Google Books.

So, in “that thinly settled and half civilized region,” Johnson only found a population of about 500, “exclusive of Indians.” He didn’t think 500 was a lot, but by some counts, that number would have seemed very high. Take the word of a European visitor to La Pointe:

Among 200 Indians, only a few white families live there. One of the boatmen gave us a name, with which we found Mr. Austrian.

And, from this Mr. Austrian, himself:

There were only about 6 white American inhabitants on the Island, about 50 Canadian Frenchmen who were married to squaws, and a number of full blooded Indians, among whom was chief Buffalo who was a descendant of chiefs & who was a good Indian and favorably regarded by the people.

~Joseph Austrian, Brother of Julius and La Pointe resident 1851-52

Who lived around La Pointe in 1850?

In her biography, William W. Warren: the Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader, Theresa Schenck describes the short life of an ambitious young man from La Pointe. William Whipple Warren (1825-1853) grew up on the Island speaking Ojibwe as his first language. His father was a Yankee fur trader from New York. His mother was a daughter of Michel and Madeline Cadotte. In his famous History of the Ojibways Warren describes the Ojibwe as people with whom he readily claims kinship, but he doesn’t write as if he is an Ojibwe person himself. However, he helped interpret the Treaty of 1847 which had definitively made him an Indian in the eyes of the United States (a fact he was willing to use for economic gain). Still, a few years later, when he became a legislator in Minnesota Territory he dismissed challenges to his claims of whiteness.

If he were alive today, Warren might get a chuckle out of this line from the South African comedian Trevor Noah.

People mocked me. Gave me names like mixed breed, half caste — I hate that term ‘half’. Why half? Why not double? Or twice as nice, I don’t know.

— Trevor Noah

William Warren did not see himself as quite the walking contradiction we might see him as today. He was a product of the time and place he came from: La Pointe. By 1850, he had left that place, but his sister and a few hundred of his cousins still lived there. Many of them were counted in the census.

What is Metis?

Half-breeds, Mixed-bloods, Frenchmen, Wiisakodewininiwag, Mitif, Creoles, Metis, Canadiens, Bois Brules, Chicots, French-of-the-country, etc.–at times it seems each of these means the same thing. At other times each has a specific meaning. Each is ambiguous in its own way. In 1850, roughly half the families in the Chequamegon area fit into this hard-to-define category.

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings around Lake Superior. London: Chapman and Hall, 1860. pg. 260-61.

We were accompanied on our trip throughout the lakes of western Canada by half-Indians who had paternal European blood in their veins. Yet so often, a situation would allow us to spend a night inside rather than outdoors, but they always asked us to choose to Irish camp outside with the Indians, who lived at the various places. Although one spoke excellent English, and they were drawn more to the great American race, they thought, felt, and spoke—Indian! ~Carl Scherzer

In describing William Warren’s people, Dr. Schenck writes,

Although the most common term for people of mixed Indian and European ancestry in the nineteenth century was “half-breed,” the term “mixed blood” was also used. I have chosen to use the latter term, which is considered less offensive, although biologically inaccurate, today. The term “métis” was not in usage at the time, except to refer to a specific group of people of mixed ancestry in the British territories to the north. “Wissakodewinini,” the word used by the Ojibwe, meant “burned forest men,” or bois brulés in French, so called because half-breeds were like the wood of a burned forest, which is often burned on one side, and light on the other (pg. xv).

Schenck is correct in pointing out that mixed-blood was far more commonly used in 19th-century sources than Metis (though the latter term did exist). She is also correct in saying that the term is more associated with Canada and the Red River Country. There is an additional problem with Metis, in that 21st-century members of the Wannabe Tribe have latched onto the term and use it, incorrectly, to refer to anyone with partial Native ancestry but with no affiliation to a specific Indian community.

That said, I am going to use Metis for two reasons. The first is that although blood (i.e. genetic ancestry) seemed to be ubiquitous topic of conversation in these communities, I don’t think “blood” is what necessarily what defined them. The “pure-blooded French Voyageur” described above by Kohl clearly saw himself as part of Metis, rather than “blanc” society. There were also people of fully-Ojibwe ancestry who were associated more with Metis society than with traditional Ojibwe society (see my post from April). As such, I find Metis the more versatile and accurate term, given that it means “mixed,” which can be just as applicable to a culture and lifestyle as it is to a genetic lineage.

One time Canadian pariah turned national hero, Louis Riel and his followers had cousins at La Pointe (Photo: Wikipedia)

The second reason I prefer Metis is precisely because of the way it’s used in Manitoba. Analogous to the mestizo nations of Latin America, Metis is not a way of describing any person with Native and white ancestry. The Metis consider themselves a creole-indigenous nation unto themselves, with a unique culture and history. This history, already two centuries old by 1850, represents more than simply a borrowed blend of two other histories. Finally, the fur-trade families of Red River came from Sault Ste. Marie, Mackinac, Grand Portage, and La Pointe. There were plenty of Cadottes, Defaults, Roys, Gurnoes, and Gauthiers among them. There was even a Riel family at La Pointe. They were the same nation

Metis and Ojibwe Identity in the American Era

When the 1847 Treaty of Fond du Lac “stipulated that the half or mixed bloods of the Chippewas residing with them shall be considered Chippewa Indians, and shall, as such, be allowed to participate in all annuities which shall hereafter be paid…” in many ways, it contradicted two centuries of tradition. Metis identity, in part, was dependent on not being Indian. They were a minority culture within a larger traditional Anishinaabe society. This isn’t to say that Metis people were necessarily ashamed of their Native ancestors–expressions of pride are much easier to find than expressions shame–they were just a distinct people. This was supposedly based in religion and language, but I would argue it came mostly from paternal lineage (originating from highly-patriarchal French and Ojibwe societies) and with the nature of men’s work. For women, the distinction between Ojibwe and Metis was less stark.

The imposition of American hegemony over the Chequamegon region was gradual. With few exceptions, the Americans who came into the region from 1820 to 1850 were adult men. If new settlers wanted families, they followed the lead of American and British traders and married Metis and Ojibwe women.

Still, American society on the whole did not have a lot of room for the racial ambiguity present in Mexico or even Canada. A person was “white” or “colored.” Race mixing was seen as a problem that affected particular individuals. It was certainly not the basis for an entire nation. In this binary, if Metis people weren’t going to be Indian, they had to be white.

The story of the Metis and American citizenship is complicated and well-studied. There is risk of overgeneralizing, but let’s suffice to say that in relation to the United States government, Metis people did feel largely entitled to the privileges of citizenship (synonymous with whiteness until 1865), as well as to the privileges of Ojibwe citizenship. There wasn’t necessarily a contradiction.

Whatever qualms white America might have had if they’d known about it, Metis people voted in American elections, held offices, and were counted by the census.

Ojibwe “Full-bloods” and the United States Census

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which

may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons. The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.~Excerpt from Article I Section II, U. S. Constitution

As I argued in the April post, our modern conception of “full-blood” and “mixed-blood” has been shaped by the “scientific” racism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The distinction, while very real in a cultural sense, was not well-grounded in biology.

The relationship of Indians (i.e. full-bloods or those living a traditional lifestyle) to American society and citizenship was possibly more contradictory then that of the Metis. In one sense, America saw Indians as foreigners on their own continent: either as enemies to be exterminated, or as domestic-dependent ward nations to be “protected.” The constitutional language about the census calls for slaves to be counted as three-fifths of a person. It says Indians shouldn’t be counted at all.

In another sense, however, the path to personhood in America was somewhat clearer for Indians than it was for African Americans. Many New England liberals saw exodus to Liberia as the only viable future for free blacks. These same voices felt that Indians could be made white if only they were separated from their religions, cultures, and tribal identities. In 1834, to avoid a second removal, the Brothertown Indians of Wisconsin petitioned congress for citizenship and the termination of collective title to their tribal lands. In 1839, their request was granted. In the eyes of the law, they had effectively become white. Other communities would follow suit. However, most Native people did not gain any form of American citizenship until 1924.

How did that play out for the Ojibwe people of Chequamegon, and how did it impact the 1850 census? Well, it’s complicated.

Race, the Census, and Classifying Households

The enumeration forms Daniel H. Johnson carried to La Pointe had more rows and columns than ever. The Seventh Census was the first to count everyone in the household by name (previous versions only listed the Head of Household with tally marks). It was also the first census to have a box for “color.” Johnson’s choices for color were “white,” “black,” and “mulatto,” forcing him to make some decisions.

He seems to have tried to follow the Indians not taxed clause strictly. 40-50% of households in the region were headed by a full-blood Ojibwe person, possibly only two of them were enumerated. You won’t find Chief Buffalo, Makadebinesi (Blackbird), Oshkinaawe, Omizhinaawe, Edawegiizhig, and their immediate families in the 1850 census. Jechiikwii’o (often called Little Buffalo) is not in the document, even though he was an early Catholic convert, dressed in “white” clothing, and counted more Metis Ojibwe among his followers than full-bloods. However, his son, Antoine Buffalo Sr. (Antoine Jachequaon) is counted. Antoine, along with George Day, were counted as white heads of household by the census, though it is unclear if they had any European ancestry (Sources conflict. If anyone has genealogical information for the Buffalo and Day families, feel free to comment on the post). A handful of individuals called full-bloods in other sources, were listed as white. This includes 90-year old Madeline Cadotte, Marie Bosquet, and possibly the Wind sisters (presumably descendants of Noodin, one of the St. Croix chiefs who became Catholic and relocated to La Pointe around this time). They were married to Metis men or lived in Metis households. All Metis were listed as white.

Johnson did invent new category for five other Ojibwe people: “Civilized Indian,” which he seemed to use arbitrarily. Though also living in Metis households, Mary Ann Cadotte, Osquequa Baszina, Marcheoniquidoque, Charlotte Houle, and Charles Loonsfoot apparently couldn’t be marked white the way Madeline Cadotte was. These extra notations by Johnson and other enumeration marshals across the country are why the Seventh Federal Census is sometimes referred to as the first to count Native Americans.

So, out of 470 individuals enumerated at La Pointe and Bad River (I’ve excluded Fond du Lac from my study) Johnson listed 465 (99%) as white. By no definition, contemporary or modern, was the Chequamegon area 99% white in 1850. The vast majority of names on the lines had Ojibwe ancestry, and as Chippewas of Lake Superior, were receiving annuities from the treaties.

There were a few white American settlers. The Halls had been at La Pointe for twenty years. The Wheelers were well-established at Odanah. Junius and Jane Welton had arrived by then. George Nettleton was there, living with a fellow Ohioan James Cadwell. The infamous Indian agent, John Watrous, was there preparing the disastrous Sandy Lake removal. Less easy to describe as American settlers, but clearly of European origins, Fr. Otto Skolla was the Catholic priest, and Julius Austrian was the richest man it town.

There were also a handful of American bachelors who had drifted into the region and married Metis women. These first-wave settlers included government workers like William VanTassel, entrepreneurs like Peter VanderVenter, adventurers with an early connection to the region like Bob Boyd and John Bell, and homesteaders like Ervin Leihy.

It is unclear how many of French-surnamed heads of household were Chicots (of mixed ancestry) and how many were Canadiens (of fully-French ancestry). My sense is that it is about half and half. Some of this can be inferred from birthplace (though a birthplace of Canada could indicate across the river at Sault Ste. Marie as easily it could a farm in the St. Lawrence Valley). Intense genealogical study of each family might provide some clarifications, but I am going to follow Kohl’s voyageurs and not worry too much about it. Whether it was important or not to Jean Baptiste Denomie and Alexis Carpentier that they had no apparent Indian ancestry and that they had come from “the true homeland” of Quebec, for all intents and purposes they had spent their whole adult lives in “the Upper Country,” and their families were “of the Country.” They were Catholic and spoke a form of French that wasn’t taught in the universities. American society would not see them as white in the way it saw someone like Sherman Hall as white.

So, by my reckoning, 435 of the 470 people counted at La Pointe (92.5%) were Metis, full-blood Ojibwe living in Metis households, or Canadians in Metis families. Adding the five “Civilized Indians” and the six Americans married into Metis families, the number rises to 95%. I am trying to track down accurate data on the of Indians not taxed (i.e. non-enumerated full-bloods) living at or near La Pointe/Bad River at this time. My best estimates would put it roughly the same as the number of Metis. So, when Johnson describes a land with a language and culture foreign to English-speaking Americans, he’s right.

Birthplace, Age, and Gender

Ethnic composition is not the only data worth looking at if we want to know what this area was like 169 years ago. The numbers both challenge and confirm assumptions of how things worked.

Let’s take mobility for example:

The young voyageur quoted by Kohl may have felt like he didn’t have a home other than en voyage, but 86% of respondents reported being born in Wisconsin. Except for ten missionary children, all of these were Metis or “Civilized Indian.” Wisconsin could theoretically mean Lac du Flambeau, Rice Lake, or even Green Bay, this but this number still seemed high to me. I’m guessing more than 14% of 21st-century Chequamegon residents were born outside the state, and 19th-century records are all about commerce, long-distance travel, and new arrivals in new lands. We have to remember that most of those records are coming from that 14%.

In September of 1850 the federal government was telling the Ojibwe of Wisconsin they needed to leave Wisconsin forever. How the Metis fit into the story of the Sandy Lake Tragedy has always been somewhat fuzzy, but this data would indicate that for a clear majority, it meant a serious uprooting.

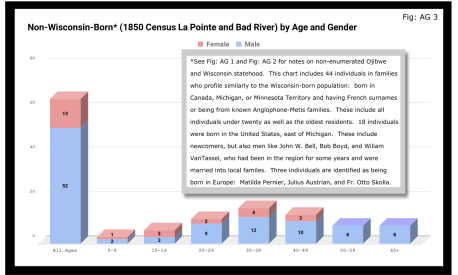

For those born outside Wisconsin, more than two-thirds reported being born in Michigan, Canada, or Minnesota Territory. These are overwhelmingly Metis or in the case of Anglo-Canadians like Robert Morrin, heads of Metis households from areas with a fur-trade tradition. Only eighteen individuals reported being born in the eastern United States. Only three reported Europe.

I had more questions than assumptions about the gender and age breakdown of the population. Would there be more women than men because of the dangerous jobs done by men or would mortality from childbirth balance that out? Or maybe widows wouldn’t be counted if they returned to the wigwams of their mothers? How would newcomers skew the age and gender demographics of the area?

Let’s take a look:

A quick glance at Figure AG 1 shows that the population skewed male 248-222 and skewed very young (61% under 20 years old). On the eve of Sandy Lake, the natural increase in the population seemed to be booming.

The hypotheses that women had higher mortality rates and were more likely to be undercounted looked good until we limit the data to the Wisconsin-born population. In Figure AG 2, we see that the male majority disappears entirely. The youthful trend, indicating large families and a growing population, continues with 66% of the Wisconsin-born population being under 20.

The male skew of the total population was entirely due to those born outside Wisconsin. This is not surprising given how much we’ve emphasized the number of men who came into the Lake Superior country to marry local women.

A look at the oldest residents in chart AG 2 and AG 3 hints at another story. Madeline Cadotte is the only Wisconsin-born person over seventy to be counted. The oldest men all came from Michigan and Canada. Why? My hypothesis is that between the fall of New France in 1759 and the establishment of Michel Cadotte’s post sometime around 1800, there wasn’t a large population or a very active fur trade around La Pointe proper. That meant Cadotte’s widow and other full bloods were the oldest locally-born residents in 1850. Their Metis contemporaries didn’t come over from the Soo or down from Grand Portage until 1810 or later.

Economics

Before the treaties, the economy of this area was built on two industries: foraging and trade. Life for Ojibwe people revolved around the seasonal harvest of fish, wild rice, game, maple sugar, light agriculture, and other forms of gathering food directly from the land. Trade did not start with the French, and even after the arrival of European goods into the region, the primary purpose of trade seemed to be for cementing alliances and for the acquisition of luxury goods and sacred objects. Richard White, Theresa Schenck, and Howard Paap have all challenged the myth of Ojibwe “dependence” on European goods for basic survival, and I find their arguments persuasive.

Trade, though, was the most important industry for Metis men and La Pointe was a center of this activity. The mid-19th century saw a steep decline in trade, however, to be replaced by a toxic cycle of debts, land sales, and annuity payments. The effects of this change on the Metis economy and society seem largely understudied. The fur trade though, was on its last legs. Again, the Austrian travel writer Carl Scherzer, who visited La Pointe in 1852:

After this discussion of the of the rates of the American Fur Company and its agents, we want to add some details about the men whose labor and time exerted such a great influence on the fate and culture of the Indian tribes. We wish to add a few explanatory words about the sad presence on La Pointe of the voyageurs or courriers du bois.

This peculiar class of people, which is like a vein of metal that suddenly disappears within the bedrock and reappears many hundreds of miles away under the same geological conditions, their light reaches the borders of the eastern Canadas. The British people, with their religion and customs, reappeared on the shores of these northern lakes only in 1808 with the Fur Company. For labor they drew on those who could carry their wares across the lakes and communicate with the Indians.

Many young men of adventurous natures left the old wide streets of Montreal and moved into the trackless primeval forests of the West. Young and strong as laborers, they soon started to adopt the lifestyle and language of the aborigines. They married with the Indians and inhabit small settlements scattered throughout those mighty lands which begin at Mackinow Island and come up the upper lake to the region of Minnesota. They almost all speak the Canadian patois along with the language of the Chippewas, the tribe with which they came into kinship. We found only a few, even among the younger generation, who understood English.

Since then, every day the population of the otherwise deserted shore of Lake Superior increases with the discovery of copper mines. The animals driven away by the whirlwind of civilization toward the west, attract the Indians with their sensitive guns, leaving La Pointe, abandoned by the Company for their headquarters at St. Paul in Minnesota. Most voyageurs left the island, having seen their business in ruins and lacking their former importance. Just a few families remain here, making a meager livelihood of hunting, fishing, and the occasional convoy of a few travelers led by business, science, or love of nature who purchase their limited resources.

From Scherzer’s description, two things are clear. It’s pretty clear from the flowery language of the Viennese visitor.Washington Irving and other Romantic-Era authors had already made the Voyageur into the stock stereotypical character we all know today. Th only change, though, is these days voyageurs are often depicted as representatives of white culture, but that’s a post for another time.

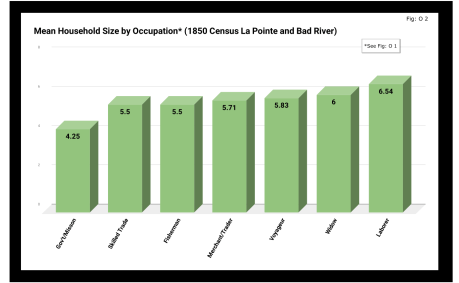

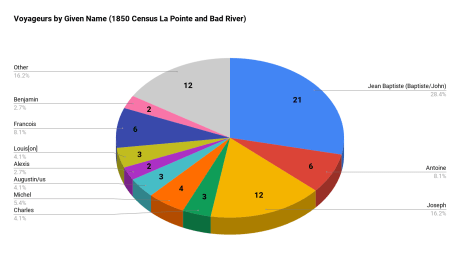

The second item, more pertinent to this post, is that a lot of voyageurs were out of work. This is especially relevant when we look at our census data. Daniel Johnson recorded the occupations of all males fifteen or over:

A full 55% of enumerated men fifteen and older still identified themselves as voyageurs in 1850. This included teenagers as well as senior citizens. All were from Metis households, though aside from farmer, all of the other occupation categories in Figure O 1 included Metis people.

A look at household sizes did not show voyageurs having to support significantly larger or smaller families when compared to the other occupation categories.

The other piece of economic data collected was value of real estate. Here we see some interesting themes:

If real estate is a good proxy for wealth in a farming community, it is an imperfect one in the Chequamegon area of 1850. If a voyageur had no home but the river and portage, then we might not expect him to put his coin into land and buildings. A teacher or Indian agent might draw a consistent salary but then live in supplied housing before moving on. With that caveat, let’s dig into the data.

Excluding the single farmer, men in the merchant/trader group controlled the most wealth in real estate, with Julius Austrian controlling as much as the other merchants combined. Behind them were carpenters and men with specific trades like cooper or shoemaker. Those who reported their occupation generally as “laborer” were not far behind the tradesmen. I suspect their real estate holdings may be larger and less varied than expected because of the number of sons and close relatives of Michel Cadotte Sr. who identified themselves as laborers. Government and mission employees held relatively little real estate, but the institutions they represented certainly weren’t lacking in land or power. Voyageurs come in seventh, just behind widows and ahead of fishermen of which there were only four in each category.

It is interesting, though, that the second and third richest men (by real estate) were both voyageurs, and voyageur shows a much wider range of households than some of the other categories: laborers in particular. With the number of teenagers calling themselves voyageurs, I suspect that the job still had more social prestige attached to it, in 1850, than say farmer or carpenter.

With hindsight we know that after 1854, voyageurs would be encouraged to take up farming and commercial fishing. It is striking, however, how small these industries were in 1850. Despite the American Fur Company’s efforts to push its Metis employees into commercial fishing in the 1830s, and knowing how many of the family names in Figure O 3 are associated with the industry, commercial fishing seemed neither popular nor lucrative in 1850. I do suspect, however, that the line between commercial and subsistence fishing was less defined in those days and that fishing in general was seen as falling back on the Indian gathering lifestyle. It wouldn’t be surprised if all these families were fishing alongside their Ojibwe relatives but didn’t really see fishing (or sugaring, etc.) as an occupation in the American sense.

Finally, it could not have escaped the voyageurs notice that while they were struggling, their former employers and their employers educated sons were doing pretty well. They also would have noticed that it was less and less from furs. Lump annuity payments for Ojibwe land sales brought large amounts of cash into the economy one day a year. It must have felt like piranhas with blood in the water. Alongside their full-blood cousins, Metis Ojibwe received these payments after 1847, but they had more of a history with money and capitalism. Whether to identify with the piranha or the prey would have depended on all sorts of decisions, opportunities and circumstances.

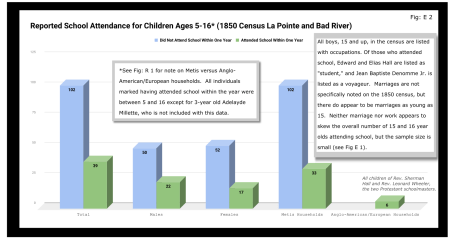

Education and Literacy

The census also collected data on education and literacy, asking whether children had attended school within the year, and whether adults over twenty could read and write. The history of white education efforts in this area are fairly well documented. The local schools in 1850 were run by the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions (A.B.C.F.M.) at the La Pointe and Odanah missions, and an entire generation had come of age at La Pointe in the years since Rev. Sherman Hall first taught out of Lyman Warren’s storehouse in 1831. These Protestant ministers and teachers railed against the papists and heathens in their writings, but most of their students were Catholic or traditional Ojibwe in religion. Interestingly, much of the instruction was done in the Ojibwe language. Unfortunately, however, the census does not indicate the language an individual is literate in. I highly recommend The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849 if you are interested in these topics.

To start with, though, let’s look at how many people were going to school:

Thirty-nine students had gone to school in the previous year. There is a lot of sample-size noise in the data, but it seems like ages 7-11 (what we would call the upper-elementary years) were the prime years to attend school.

Overall, most children had not attended school within the year. Attendance rates were slightly higher for boys than for girls. White children, all from two missionary families, had a 100% attendance rate compared to 24% for the Metis and “Civilized Indian” children.

We should remember, however, that not attending school within the year is not the same as having never attended school. Twelve-year-old Eliza Morrin (later Morrison) is among the number that didn’t attend school, but she was educated enough to write her memoirs in English, which was her second language. They were published in 2002 as A Little History of My Forest Life, a fascinating account of Metis life in the decades following 1854.

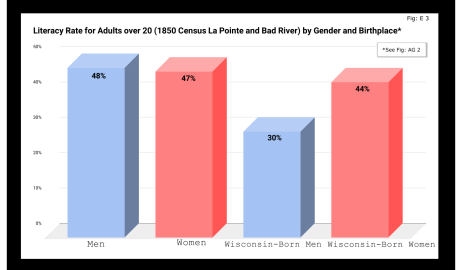

Eliza’s parents were among the La Pointe adults who could read and write. Her aunt, uncle, and adult cousins in the neighboring Bosquet (Buskey) house were not. Overall, just over half of adults over 20 were illiterate without a significant gender imbalance. Splitting by birthplace, however, shows the literacy rate for Wisconsin-born (i.e. Metis and “Civilized Indian”) was only 30%, down from the overall male literacy rate of 48%. For Wisconsin-born women, the drop is only three points, from 47% to 44%. This suggests Metis women were learning to read while their husbands and brothers (perhaps en voyage) were not.

And this is exactly what the data say when we split by occupation. The literacy rate for voyageurs was only 13%. This beats fisherman–all four were illiterate–but lagged far behind all other types of work.

If education was going to be a factor in the economic mobility of unemployed voyageurs, the trends weren’t looking good.

Odds and Ends

Two marriages were reported as occurring in the year previous to the census: Peter and Caroline Vanderventer and Pierre and Marguerite Robideaux (ak.a. Peter and Margaret Rabideaux). Though married, however, Caroline was not living with her husband, a 32-year old grocer from New York. She (along with their infant daughter) was still in the home of her parents Benjamin and Margaret Moreau (Morrow). The Vanderventers eventually built a home together and went on to have several more children. It appears their grandson George Vanderventer married Julia Rabideaux, the granddaughter of Peter and Margaret.

I say appears in the case of George and Julia, because Metis genealogy can be tricky. It requires lots of double and triple checking. Here’s what I came across when I once tried to find an unidentified voyageur known only as Baptiste:

Sometimes it feels like for every Souverain Denis or Argapit Archambeau, there are at least 15 Jean-Baptiste Cadottes, 12 Charles Bresettes, 10 Francois Belangers and 8 Joseph DeFoes. Those old Canadian names had a way of persisting through the generations. If you were a voyageur at La Pointe in 1850, there was nearly a 30% chance your name was Jean-Baptiste. To your friends you might be John-Baptist, Shabadis, John, JB, or Battisens, and you might be called something else entirely when the census taker came around.

The final column on Daniel Johnson’s census asked whether the enumerated person was “deaf and dumb, blind, insane, idiotic, pauper, or convict.” 20 year-old Isabella Tremble, living in the household of Charles Oakes, received the unfortunate designation of idiotic. 26-year-old Francois DeCouteau did not have a mark in that column, but had “Invalid” entered in for his occupation. It’s fair to say we’ve made some progress in the treatment of people with disabilities.

Final Thoughts

I am not usually a numbers person when it comes to history. I’ll always prefer a good narrative story, to charts, tables, and cold numbers. Sometimes, though, the numbers help tell the story. They can help us understand why when Louis Gurnoe was killed, no one was held accountable. At the very least, they can help show us that the society he lived in was under significant stress, that the once-prestigious occupation of his forefathers would no longer sustain a family, and that the new American power structure didn’t really understand or care who his people were.

Ultimately, the census is about America describes itself. From the very beginning, it’s never been entirely clear if in E. pluribus unum we should emphasize the pluribus or the unum. We struggled with that in 1850, and we still struggle today. To follow the Department of Commerce v. New York citizenship case, I recommend Scotusblog. For more census posts about this area in the 19th century, keep following Chequamegon History.

Sources, Data, and Further Reading

-

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin a History of an Ojibwe Community ; Volume 1 The Earliest Years: the Origin to 1854. North Star Press of St. Cloud, Inc., 1854.

-

Satz, Ronald N. Chippewa Treaty Rights: the Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. University of Wisconsin Press, 1997.

-

Original Census Act of May 23, 1850 (includes form and instructions for marshals). (PDF)

-

Compiled data spreadsheets (Google Drive Folder) I’ll make these a lot more user friendly in future census posts. By the time it occurred to me that I should include my tables in this post, most of them were already done in tally marks on scrap paper.

-

Finally, these are the original pages, scanned from microfilm by FamilySearch.com. I included the image for Fond du Lac (presumably those living on the Wisconsin side of the St. Louis River) even though I did not include it in any of the data above.

By Amorin Mello

In our Penoka Survey Incidents series earlier this year, we followed some of the adventures and schemes of Albert Conrad Stuntz circa 1857. The legacy of Albert’s influential survey still defines the geopolitical landscape of the Penokee Mountains to this day. However, Albert’s work during the late 1850s was relatively minor in comparison to that of his brother, George Riley Stuntz, during the early 1850s. The surveying work of George and his employees started in 1852 and enabled the infamous land speculators and townsite promotors of Superior City to manifest their schemes by early 1854 (months before the Treaty of La Point occurred later that year).

Among the men that worked with George was Augustus Hamilton Barber. Sometime around 1850, Augustus had followed his Grandparents, Aunts, Uncles, and Cousins from the Barber family of Lamoille County, Vermont, to Lancaster in Grant County, Wisconsin. After a short career as a school teacher in Grant County, Augustus came to Lake Superior in 1852 employed by George as a Chainman under his contract with the United States General Land Office to survey lands at the Head of Lake Superior.

Before taking a closer look at the Barber Papers, let’s examine the lives and affairs of other surveyors and speculators along the southwest shore of Lake Superior, starting with George Riley Stuntz and his production of these Exterior Field Notes (June of 1852):

Duluth and St. Louis County, Minnesota;

Their Story and People

By Walter Van Brunt, 1921, pages 64-65.

First Settler.– The honor, for both Superior and Duluth, must presumably go to George R. Stuntz. He came in 1852, and settled in 1853. Several were earlier of course, but can hardly be considered to have been legitimate independent settlers. Carlton had been on the ground, at Fond du Lac, for some years, but he was Indian agent; Borup and Oaks had spent their time between La Pointe and Fond du Lac, but were then at St. Paul, and mainly interested in the development of that city, and in fur trading. Wm. R. Marshall stated that he “was on the lake as early as 1848,” but not to settle and he did not come again until 1857. Wm. R. Marshall and George R. Stuntz were fellow-surveyors, in federal pay, “back in the ’40s,” but Marshall did not seek to take the place of Stuntz as premier pioneer at the head of Lake Superior. As a matter of fact, although “on the lake as early as “1848,” Marshall did not then get nearer to Duluth than La Pointe, where he met “Borup and Oaks, the principal traders, Truman Warren, George Nettleton, Cruttenden, Wattrous, Rev. Sherman Hall, E. F. Ely and others.” It is quite possible that Stuntz was with Marshall in 1848, for that was the year in which Stuntz first entered Minnesota territory “having charge of a surveying party that was working near Lake Pepin and in what is now Washington County.”

The “Heart of the Continent.”– George R. Stuntz prepared the way for the first attempt at white settlement at the head of Lake Superior. He surveyed the land on the Wisconsin side, within a year of beginning which survey, in 1852, the first settlers began to appear. George R. Stuntz came by direction of George B. Sargent, who at the time was surveyor-general of the Iowa, Wisconsin and Minnesota district for the federal government, his headquarters being at Davenport, Iowa. In that year, states Carey, “he surveyed and definitely located a portion of the northeastern boundary line between Minnesota and Wisconsin, starting from the head of navigation on the St. Louis River, at Fond du Lac, and running south to the St. Croix River.” Stuntz himself stated: “I came in 1852. I saw the advantages of this point (Minnesota Point) as clearly then as I do now (1892). On finishing the survey for the government, I went away to make a report, and returned the next spring and came for good. I saw as surely then as I do now that this was the heart of the continent commercially, and so I drove my stakes.”

![Group of people, including a number of Ojibwe at Minnesota Point, Duluth, Minnesota [featuring William Howenstein] ~ University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/howenstein-minnesota-point.jpg?w=300&h=259)

Group of people, including a number of Ojibwe at Minnesota Point, Duluth, Minnesota [featuring William Howenstein in 1872?] ~ University of Minnesota Duluth

The Vanguard.– He did not come alone, needing of course assistants in the work of surveying, but he was in charge of the work, Gand necessarily takes first place in the accounting. William C. Sargent, son of George B. Sargent, stated in 1916, that his father “came here (Duluth) first in 1852 with George R. Stuntz and Bill Howenstein,” and goes on to state “a word of those two grand men, George R. Stuntz and Bill Howenstein.” He believed that “to George R. Stuntz, more than to any other man belongs the honor (of) opening up that region,” and of Howenstein, he said: “And old Bill Howenstein, one of the best ever, and always my very good friend, a kindly body, with a quaint dry humor unsurpassed and seldom met with in these later days. I had many an interesting chat with him, in his home on Minnesota Point, that he built in 1852, and lived in until his death, some years ago.” Bill Howenstein, undoubtedly was of Stuntz’ party in 1852, but it is doubtful whether he built a log house on Minnesota Point in that year. As to General Sargent’s visit in 1852. If he did come then, it was probably only a flying visit. His interest in the head of Lake Superior in 1852 reached only to the extent of directing Stuntz to survey it. He, himself, had the surveying business of three states to attend to.

The New York Times

[December 11, 1852]

The Region about the Southwest End of Lake Superior.

Mr. Stuntz, of Grant County, Wis., has been deputed by the general Land Surveyor of this Northwest District to lay off such a tract of land about the southwest point of the lake into townships and sections, as emigrants will earliest require. He returned via La Pointe and Stillwater last week. We have obtained from him some new views of that region. From Fond du Lac, a trading post situated 11 miles inland on the St. Louis River, eastward, for perhaps 50 miles, the margin of the lake is a flat strip of land reaching back to a rocky ridge about 11 miles off. The soil of this flat land is a rich red clay. The wood is white cedar and pine of the most magnificent growth. The American line is beyond the mouth of the St. Louis and Pigeon rivers. It evidently abounds in copper, iron and silver. The terrestrial compass cannot be used there, so strong is the attraction to the earth. The needle rears and plunges “like mad.” Points of survey have to be fixed by the solar compass.

The Indian and half breed packmen have astonishing strength. One Indian, who is described by the others as being as large as two men, carried for a company of 11 men provisions for ten days, viz: one barrel of flour, half barrel of pork and something else, beside the utensils. Mirage is a common phenomenon is Spring and Summer. For the bays not opening as soon as the main lake, or not cooling so early, an object out on the lake, is viewed from the shore, through a dense medium of air and a thin medium. Hence is a refraction of rays which gives so many wonderful sights that the Chippewas call that the spirit or enchanted land. Sail vessels which are really 40 miles off, are seen flapping and bellying about almost within touch. Turreted Islands, look heavy and toppling towards the zenith. Forests seem to leap from their stems and go a soaring like thistles for the very sport of it.

The ice did not leave some of the bays till the 10th of June. The fish are delicious, especially the salmon trout. But little land game. Mr. Stunts calculates on wonderful enterprises in that country after the opening of the Saut Canal.

Mr. S. describes La Pointe a town of the Lake, as being situated at the head of a bay some 25 miles from the high lake, and secluded from the lake by several islands. He saw there a warehouse 300 feet long, built of tamarac poles, and roofed with bark. This building is very much warped by the pressure of age ; it is entered by a wooden railway. The town is dingy and dreary. He saw a most luxurious garden by the former residence of Dr. Borup. It contained a variety of fruit trees and shrubs, such as plums, cherries, apples, pears, currants, &c.

Cover of Stuntz’s Exterior Field Notes (August-October 1852) ~ Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records: Original Field Notes and Plat Maps

George Riley Stuntz was also assisted by his brother Albert Conrad Stuntz as well as the African-Chippewa mixed-blood Stephen Bonga employed as an Axeman. To learn more about the interesting Bonga (Bonza) family and Stephen as “the first white child born at the head of Lake Superior,” read pages 39-41 of The Black West by William Loren Katz (1971), and pages 131-34 of Black Indians also by Katz (2012).

The Eye of the North-west: First Annual Report of the Statistician of Superior, Wisconsin

By Frank Abial Flower, 1890

GEORGE R. STUNTZ, DEPUTY U. S. SURVEYOR [pages 50-52]

In 1852 George R. Stuntz took a contract to run the township lines in this part of the country, including the state boundary, and filed with the land-office at Dubuque a rude map of the head of the lake, on the Wisconsin side, in December of that year. He took a new contract and returned in the spring of 1853 to survey the copper range around Black River, a few miles south of Superior. He brought seeds with him and planting them on the Namdji, raised a quantity of vegetables; they grew to great size. he also built a trading-post on Minnesota point near the present light-house, and a mill on Iron River in Bayfield county. In respect of these operations W. W. Ward writes from Morley, Mo.:

The first lumber of any description produced locally, other than by “Whip sawing”, was at Iron River, Wisconsin about forty miles from Superior on the South Shore of Lake Superior.

George R. Stuntz with William C. Howenstein, Andrew Reefer and George Falkner built and operated a water power “up and down” sawmill at the falls on Iron River about a half a mile from the Lake, capable of cutting three thousand feet of lumber a day. The writer has several 1 1/4 inch absolutely “clear” White Pine boards 24 and 26 inches wide and 18 feet long that were originally stored in a loft to be used in building a skiff. This mill was built in 1854 and the lumber was floated up the Lake to Superior, Oneota and Fond du Lac…

~ Superior, Wisconsin, papers, 1831-1942 ([unpublished])

From “A Pioneer of Old Superior” by Lillian Kimball Stewart

“In the summer of ’54 the Sam Ward plying between the Sault and any port on Lake Superior, brought on every trip a goodly number of emigrants, speculators, and tourists, bent on seeing the new “city” of Superior. Stuntz’s dock was located near an Indian village, so that every traveler as well as every piece of freight or baggage was subject to inspection by braves, squaws, and papooses before receiving a passport to the shore across the bay…”

~ Superior, Wisconsin, papers, 1831-1942 ([unpublished])

“It was in the spring of 1853 that Mr. Stuntz, Deputy U. S. Surveyor, received his second contract to survey and run the township lines taking in the range around Black River Falls, a portion of Left-hand River country and that part where Superior now is. In the latter part of April that year he organized a party – viz., Nat. W. Kendall, James McKinzie, Pain Bradt, James McBride, Harvey Fargo, Wm. H. Reed, John Chisholm, Joseph Latham, Augustus Barber, and your humble servant. Procured three birch-bark canoes and supplies at Stillwater, Minn.: left there the first day of May, passed up the St. Croix River to its head, made a portage of about two and a half miles into the headwaters of the Brule River, down said river into Lake Superior, thence up the lake to what was called the entry of St. Louis Bay [now Superior Bay], and landed on Minnesota Point in the early part of June. At that time there were no white settlers in this end of the lake – all Chippewa Indians and ‘breeds’ – scarcely a stick missing on that side of the bay where Superior City now stands. We finished the surveying contract and went in early fall down to Iron River, built a double log-shanty, and made other preparations for the construction of a saw mill. Here the first lumber was made at the head of the lake and the first road opened through to the settlement on the St. Croix. The following February, Mr. Stuntz having a trading-post on Minnesota Point [then Stuntz’s Point], I went there and assisted in building a block-house and steamboat pier, and found improvements and a few log-shanties built where old Superior now is located.”

[…]

HUSTLING FOR TOWNSITES [pages 58-60]

VI. – Superior.

Vincent [Roy Jr.] had barely emerged from the trouble just described when it was necessary for him to exert himself in another direction. A year or so previously he had taken up a claim of land at the headwaters of Lake Superior and there was improvement now on foot for that part of the country, and danger for his interests.

The ship canal at Sault St Marie was in course of construction and it was evidently but a question of days that boats afloat on Lakes Huron and Michigan would be able to run up and unload their cargo for regions further inland somewhere on the shore at the further end of Lake Superior, at which a place, no doubt, a city would be built. The place now occupied by the city of Superior was suitable for the purposes in view but to set it in order and to own the greatest possible part of it, had become all at the same time the cherished idea of too many different elements as that developments could go on smoothly. Three independent crews were struggling to establish themselves at the lower or east end of the bay when a fourth crew approached at the upper or west end, with which Vincent, his brother Frank, and others of LaPointe had joined in. As this crew went directly to and began operations at the place where Vincent had his property it seems to have been guided by him, though it was in reality under the leadership of Wm. Nettleton who was backed by Hon. Henry M. Rice of St. Paul. Without delay the party set to work surveying the land and “improving” each claim, as soon as it was marked off, by building some kind of a log-house upon it. The hewing of timber may have attracted the attention of the other crews at the lower end about two or three miles off, as they came up about noon to see what was going on. The parties met about halfway down the bay at a place where a small creek winds its way through a rugged ravine and falls into the bay. Prospects were anything but pleasant at first at the meeting; for a time it seemed that a battle was to be fought, which however did not take place but the parceling out of ‘claims’ was for the time being suspended. This was in March or April 1854. Hereafter some transacting went on back the curtain, and before long it came out that the interests of the town-site of Superior, as far as necessary for efficient action, were united into a land company of which public and prominent view of New York, Washington, D.C. and other places east of the Mississippi river were the stockholders. Such interests as were not represented in the company were satisfied which meant for some of them that they were set aside for deficiency of right or title to a consideration. The townsite of the Superior of those days was laid out on both sides of the Nemadji river about two or three miles into the country with a base along the water edge about half way up Superior bay, so that Vincent with his property at the upper end of the bay, was pretty well out of the way of the land company, but there were an way such as thought his land a desirable thing and they contested his title in spite of his holding it already for a considerable time. An argument on hand in those days was, that persons of mixed blood were incapable of making a legal claim of land. The assertion looks more like a bugaboo invented for the purpose to get rid of persons in the way than something founded upon law and reason, yet at that time some effect was obtained with it. Vincent managed, however, to ward off all intrusion upon his property, holding it under every possible title, ‘preemption’ etc., until the treaty of LaPointe in the following September, when it was settled upon his name by title of United States scrip so called, that is by reason of the clause, as said above, entered into the second article of that treaty.

The subsequent fate of the piece of land here in question was that Vincent held it through the varying fortune of the ‘head of the lake’ for a period of about thirty six years until it had greatly risen in value, and when the west end was getting pretty much the more important complex of Superior, an English syndicate paid the sum of twenty five thousand dollars, of which was then embodied in a tract afterwards known as “Roy’s Addition”.

~ Biographical Sketch – Vincent Roy Jr; Vincent Roy Jr. Papers.

Up to the time of the survey in the spring of 1854 all was chaos as to lands west of the claims of Robertson, Nelson, Baker and their party. There could be no titles or bona fide purchases, as only the mouth of the Nemadji had been surveyed. There were really three “townsite” companies— Robertson, Nelson and Baker, with their associates J. A. Bullen, J. T. Morgan, E. Y. Shelly, August Zachau, C. G. Pettys, Abraham Emmett, and perhaps others, forming one which had the surveyed lands next to the Nemadji. West of them were Francis Roy, Benjamin Cadotte, Robert Bothwick, Basil Dennis, Charles Knowlton and nearly a dozen half-breeds, mostly brought from Crow Wing by Nettleton in the interest of what was known as the “Hollinshead crowd”—Edmund and Henry M. Rice, George L. Becker, Wm. and George W. Nettleton, Benjamin Thompson, James Stinson and W. H. Newton. Still farther west were Benjamin W. Brunson, A. A. Parker, R. F. Slaughter, C. D. Kimball, Rev. E. F. Ely, George R. Stuntz, Bradley Salter, Joseph Kimball, Calvin Hood, and others who proposed to call their town Endion—”Ahn-dy-yon,” the Chippewa for “home.”

B. W. Brunson, still a resident of St. Paul, has described the contest in writing. He says:

“Believing Superior would become of importance I went there in February, 1854, with R. F. Slaughter. We found some Ontonagon parties had claimed on the bay and we bought an interest in their claims and began to lay out a city and make improvements. While surveying the town, and when we had the same so far completed as to make a plat of it, the township having been subdivided by a good surveyor, then it was that Vincent Roy, Basil Dennis, Charles Brissette and Antoine Warren, accompanied by twenty-one other half-breeds and some four or five white men, headed, led and directed by one Stinson and one Thompson, who were acting for themselves and as agents of the company, came upon the lands to make their claims and avail themselves of pre-emption rights as citizens of the United States. These men were in the employ of the company for the purpose of making claims, and there was a claimant for each and every quarter-section as fast as the surveyor set the quarter-post. They had commenced the day before, with or at the same time the surveyor commenced his work. The timber being dense and there being a strong force, they were able to build an 8×10 cabin and cover it with boughs, upon each quarter, and then overtake the surveyor before he could establish the next quarter, thus taking the land as they went, and in that manner were progressing when they came upon the land marked out and occupied by us.“

The meeting of the two hostile parties occurred on the banks of the deep slough in what is now called Central Park. Nothing but the timidity of the half-breeds prevented bloodshed. Brunson was armed and intended to, and did stand his ground. Thompson, one of the pluckiest of men, was also armed, having two revolvers, and was prepared and intended to proceed. The Indians, not being armed, did not wish to engage in a battle where the leaders only were prepared to fight; and so there was no physical conflict, though a state of chaos and bad feeling continued for some time. Several cabins were demolished, Brunson’s party entirely cutting in pieces a house built by Basil Dennis on the ground now occupied by Dr. Conan’s fine residence.

A long legal contest followed. Finally in 1862-63 patents issued from the government to three men—S. W. Smith, Lars Lenroot and Oliver Lemerise—chosen as trustees of the townsite for the benefit of actual occupants. Thus those who claimed to be proprietors of, but not settlers on the townsite, lost their lands as well as their labor. In the winter of 1853-54 Henry M. Rice asked the Commissioner of the General Land Office whether, when lands which had not been surveyed were claimed for a townsite they would be liable to pre-emption as soon as the survey should be made. The answer was in favor of pre-emption; and that is how those who with Brunson put money into Superior City townsite lost it. The actual settlers got the townsite, the patent being made to the three trustees named who divided the plat, containing 240 acres with riparian rights in Superior Bay, and deeded lots to occupants and purchasers. It may be proper to mention here that a little plat of thirty-four acres, with riparian rights in the bay, and known as Middletown, went through a similar siege of litigation and was finally patented to three trustees —Urguelle Gouge, Louis Morrisette and Nicholas Poulliott—for the benefit of actual occupants. These decisions did not come until the “city” had collapsed and the land become nearly worthless.

The New York Times

[June 19th, 1858]

WESTERN LAND FRAUDS.

More Blood in the Body than Shows in the Face – Land Frauds in the Northwest – The Superior City Controversy – Pre-emptions by Swedes and Indians

Washington, Thursday, June 17, 1858.

There are some interesting matters here besides what takes place in Congress, and I propose from time to time to touch upon them. An expenditure of $60,000,000 per annum does not cover all the pickings and stealings that “prevail” in our hereabouts. Senator RICE did not tell all he knew about land-office operations, when he testified to the value of the Fort Snelling property. Nobody is better aware than he that the tract would be much better to cut up into town lots than Bayfield was when he bought it for a few cents an acre, and sold it for hundreds of dollars. If we could find out all that Senator BRIGHT knows of these matters, one could learn how to become a millionaire at very small expense of brains or labor. Indian treaties and land-office jobbing have made more men rich than care to tell of it – ask General CASS if this is not so.

Seeing a bushel-basket of papers in the Interior Department the other day, I was curious to know what the kernel might be to all that rind, and made inquiry in the premises. I was told that they enveloped the case of Superior City. I cast my eye over some of them, and noticed that an argument was filed on behalf of one of the parties by Mr. Senator BRIGHT – or rather with Senator BRIGHT’S indorsement. This whetted my desire of knowledge, and I ran my eye over the paper in question, which was from the pen of a Minnesota Judge and was without exception the richest document I ever saw intended for a judicial or administrative tribunal. The substance of it was that the opinion of the Attorney-General CUSHING in the case was absurd, the adoption of his views by the Interior Department preposterous, and the action of the local Land office at Superior, in defining the status of certain half-breed Indians on the most abundant testimony, corrupt. It was clear enough that such a document required at least a senatorial indorsement to justify its reception. Nobody can suppose for a moment that Senator BRIGHT has any interest in the result of the case, or that he expected to influence the judgement of his friend, HENDRICKS, (Commissioner of the General Land Office,) by appearing in it. That would be too strong an inference to draw from so meek a fact ; and yet the malicious might suggest it as an apprehension.

Original Proprietors of Superior featuring James Stinson, Benjamin Thomson, Dr. W.W. Coran, U.S. Senator Robert J Walker, George W. Cass, and Horace Bridge. Featured in The Eye of the North-west, pg. 8.

From the printed argument of Senator BRIGHT’S friend, and from a private abstract of the testimony in the case, and a few items I have picked up in the Land Office, I think it will be in my power to indite an epistle that may excite some attention. At the Southwestern extremity of Lake Superior, there is a tract of land, which is expected some day to become the cite of a large city. Being aware of its great advantages for this purpose, a St. Paul speculator by the name of THOMPSON, and a Canadian operator by the name of STINSON, undertook to possess themselves of it as long as as in the early part of General PIERCE‘S administration, by vicarious preemptions. In this plan they were assisted by some official gentlement, who shared in the spoils, and patents were ground out in double-quick time, or certificates issued to Swedes and Indians for the benefit of this STINSON and THOMPSON, and their associate speculators.

More Proprietors of Supeior from The Eye of the North-west, pg. 9.

In the Summer of 1854, this Mr. STINSON, headed a gang of Swedes and led them from Swede Lake, in the Territory of Minnesota, to Lake Superior, guiding them in person to the tracts he wished them to preempt. These men were ignorant of our language and of our laws, and were used by STINSON to “settle” their tracts, “prove up” their claims, and “convey” to him, the said STINSON, without knowing either the frauds they were practicing, or the rights which they might have secured to themselves if they had been acting in good faith. In the Land Office at Hudson, where these frauds were perpetrated, there was a notary public, who drew the deeds to STINSON, got the signatures of the Swedes to them and took the acknowledgements, immediately after the preemption oath had been administered – the Swedes thinking the whole operation a part of the preemption process. The terms were said to be $30 a month, and a bonus of $15 on the consummation of the bargain. The names of these Swedes were Aaron Peterson, Martin Larson, Peter Nelson, John Johnson, Sven Magnassan, Lorenz Johnson, Peter Norell, Sven Larson, Andreas Senson, Johannes Helon, Johannes Peterson, and Peter Erickson. These “preemptors,” for their own benefit, all “proved up” at Hudson, and the very same day they made conveyances to STINSON. The same thing is true of another Swedish invasion that was made in the Summer of 1855. In that year three Swedes – Old Westerland, Andrew Walmart, and Israel Janssen – commenced their settlements June 11, proved up June 22, and conveyed to STINSON June 22 – eleven days being sufficient for the whole operation. The records of the Land Office at Superior, and of the Register of Deeds of Douglas County, show these facts. They are well known in the General Land Office.

But Mr. STINSON did not operate through Swedes alone. He and his friend THOMPSON worked with half-breed Indians also. In March, 1854, he and THOMPSON followed up the Government Surveys with a gang of Chippewa half-breed Indians. The whole gang made preemptions in Douglas County, under the guidance of THOMPSON and STINSON, who hired them at La Pointe, and convered a large portion of a township with their fraudulent pre-emptions, which were proved up simultaneously, and simultaneously conveyed to the attorney of THOMPSON and STINSON. The names of all of this gang appear on the tract books in the General Land Office. These were Joseph Lamoureaux, Joseph Defaut, Joseph Dennis, Joseph Gauthier, Francis Decoteau, John B. Goslin, George D. Morrison and Levi B. Coffee, all preemptors for these land-sharks. There were three or four more half-breeds in the gang, who ran foul of some eight or ten American citizens who were seeking to save a slice of this Territory from Swedish and Indian preemption, and lay out a town site there under the law. This was the origin of the Superior City controversy, which has been pending some three or four years in the various land offices, and which has accumulated the basket of papers which first drew my attention to a case of such interesting dimensions. The contest is nominally between three or four Chippewa half-breeds claiming some three hundred acres as a town site. But the Indians are not merely bogus citizens, they are bogus pre-emptors in the bargain, for they were the hired men of THOMPSON & STINSON.

Mr. CUSHING decided in this controversy, before it was so settled by the Dred Scott case, that a half-breed Indian, receiving annuities as such, recognized as a dependent of a tribe, and the beneficiary of treaty stipulations, could become a citizen of the United States only by some positive act of Federal legislation ; that he could not, of his own volition, or by the laws of a State, change his condition from that of an Indian to that of a Federal citizen. Strange as it may seem, it appears that this part of the Dred Scott is repudiated by Mr. Commissioner HENDRICKS, who thinks a state cannot make a Federal citizen of a man with a drop of negro blood in his veins, but that the Commissioner of the General Land Office may naturalize Indians, ad libitum, without statute or judgement to sustain him.

I am curious to see how this controversy will be decided. The General Land Office upheld STINTSON’S Swedish preemption, on the ground that the frauds were discovered too late for the Commissioner to interefere. Whether or not STINSON hasmade any negro preemptions does not appear. It was too cold at the end of the lake for negroes to flourish much. But now it is to be settled in a case where the attempted frauds have been seasonably discovered, whether or not a Canadian adventurer can preempt whole townships of the Public Lands by the agency of a gang of half-breed Indians, and procure patents for them when the facts are known to the Federal authorities.

The pre-emptive right. Homesteads.

~ Superior, Wisconsin, papers, 1831-1942 ([unpublished])

Detail of Superior City townsite at the head of Lake Superior from Stuntz’s 1854 Plat Map of Township 49 North Range 14 West.

Early history of Superior should make mention of this right of acquisition, since there under, titles to government land were derived. Any qualified person might acquire title to one hundred and sixty acres of land by settling thereon, erecting a dwelling and making other improvements. Such person was to be twenty-one years of age, either male or female, or the head of a family whether man or woman.

Proof of each settlement was required to be made on a certain day at the United State Land Office and upon the payment of two hundred dollars with the taking of a required oath, the preemptioner got his one hundred and sixty acres of land.

But the whole proceeding, was far from straight, as a general thing, and in fact often amounted to a fraud.

“In the first place, Superior was backed by a powerful company of Democratic politicians and Government bankers in Washington, while the northern and northeastern portions of the state were still held by the Indians. This Superior company sought a connection with the Mississippi river, to obtain which they urged in congress the passage of a land grant bill, offering ten sections to the mile to aid in the construction of a railroad from Milwaukee to some point on Lake St. Croix, on the western boundary of the state of Wisconsin.”

~ History of Duluth and St. Louis County, Past and Present,

Volume 1, page 230.

Hence the whole country, in and about Superior, was dotted with preemption cabins, which were little more than logs piles up in walls, without floors, or windows, often with brush for a roof, a hole therein for a chimney and perhaps for a door. A slashing of half an acre or so of trees was the “improvement” so called. A very barbarous travesty, it was, upon a white man’s home and farm. Here is an instance, where as was said, a certain doctor of divinity laid claim to a quarter section of land, now in the midst of this city.

One day he sought “to prove up” his preemption, and one Alfred Allen was his witness, and they asked Allen, “Was the pre-emptions shanty good to live in?“, the law requiring a good habitable house on the claim. And Alf said “Yes, good for mosquitoes.” The Reverend said “Pshaw! Pshaw!” Meanding to upbraid or caution the witness who thereupon only protested and adjured the harder. The difficulty was somehow smoothed over, through some mending of the proofs, and perhaps connivance on the part of persons charged with administration of the United States land laws.

Nevertheless, it is interesting to member that upon rude and rough proceedings, such as are herein alluded to, rest at bottom the titles and claims to everything we own in the nature of lots, blocks, and land.

From: Statements of Hiram Hayes. Mr. Hayes came to Superior in 1854.

History of Duluth and St. Louis County, Past and Present, Volume 1

By Dwight Edwards Woodbridge, et al, 1910

GEORGE R. STUNTZ. [pages 229-231]

One of the earliest settlers at the head of the lakes was Mr. George E. Stuntz, who a short time ago joined the great majority. Before his death Mr. Stuntz wrote of his pioneer experiences as follows:

“In July, 1852, I came to the head of Lake Superior to run the land lines and subdivide certain townships. When I arrived at the head of the lakes there was nothing in Duluth or Superior. There was no settlement. The old American Fur Company had a post at La Pointe, at the west side of Madeline Island.

“In 1853 I got the range subdivided, and also in Superior, townsite 49, range 13. During the same year, later, in my absence, there came parties from the copper district of upper Michigan and located claims upon the range. They were principally miners. During the same year I built a residence on Minnesota Point under treaty license before the territory was sold to the Government. At that time there were only missionaries or license traders in the tract, as it belonged to the original Indian territory. In 1852, at Fond du Lac, there was a trading post and warehouse, in which I stored my goods on my arrival. In the fall of 1853 I bought three yoke of cattle and two cows at St. Croix Falls and brought them to the mouth of the Iron river, and had to cut a road thirty miles through the dense forest so as to get the oxen, cows and cart through. Later in the fall of 1853 I came through with an extra yoke of oxen, buying provisions, etc., and on coming up to Superior I found quite a settlement of log cabins. These settlers were anxious to get to the United States land office, then at Hudson, Wis. A dense forest intervened. We organized a volunteer company in January, 1854, to cut a road from old Superior to the nearest lumber camp on the St. Croix river, I furnishing two barrels of flour, provisions, pony and dog train, necessary to carry the provisions for a gang of seventeen men. The road was completed in twenty days, the snow being at that time two feet deep. This cut through a direct road to Taylor’s Falls and Stillwater. In 1854 I completed a mill on the Iron river and employed a man to superintend it, and I remained at Minnesota Point, my trading post, where I had first taken out the license. In the same year I took a contract to subdivide two townships located in Superior, townships 48-49, range 15, and afterward I attended the treaty at the time the Indians sold this country to the Government.

Before the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe could be ratified in Washington, D.C., the oral description agreed upon during the negotiations for exterior boundaries of the Chippewa treaties had to be surveyed with the tribe, documented, and delivered to Washington, D.C. before 1855. It is not clear who was involved with the exterior boundaries of these reservations; whether it was Stuntz, Barber, and/or others from their party.

“There were 5,000 Indians present with their chiefs. It was the biggest assemblage of Indians ever held at Lake Superior at this period of the country’s history. It took a month to pacify the troubles that grew among the different tribes in regard to their proportionate rights. This treaty was sent to congress September [30], 1854, and was ratified and became law in January, 1855.

To be continued in 1854…