1839 Petitions against Payments at La Pointe

October 10, 2025

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

Previously we featured 1837 Petitions from La Pointe to the President about $100,000 Payments to Chippewa Mixed-Bloods from the 1837 Treaty of Saint Peters, and 1838 more Petitions from La Pointe to the President about relocating the Payments from St. Croix River to Lake Superior. Those earlier Petitions were from Chief Buffalo and dozens of Mixed-Bloods from the Lake Superior Chippewa Bands, setting precedence for La Pointe to host the 1842 Treaty and 1854 Treaty in later decades.

Today’s post features 1839 Petitions against Payments at La Pointe. These petitioners appear to be looking to get a competitive edge against the American Fur Company monopoly at La Pointe, by moving the payments south across the Great Divide into the Mississippi River Basin.

For more information about the $100,000 Payments at La Pointe in 1839, we strongly recommend Theresa M. Schenck’s excellent book All Our Relations: Chippewa Mixed-Bloods and the Treaty of 1837.

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs:

La Pointe Agency 1831-1839

National Archives Identifier: 164009310

April 9, 1839

from Joseph Rolette at Prairie du Chien

to the Superintendent of Indian Affairs

Received April 27, 1839

Prairie du Chiene 9th April 1839

T.H. Crawford Esq’r

Commissioner of Ind’n affairs

Washington

You must excuse the liberty I take in addressing you once more – presuming you are not well acquainted yet with this Country, I am requested by the Chippewaw half Breeds that remain in this Country, that it is with regret they have heard that the payment allowed to them in the treaty of the 29th July 1837 is to be made on Lake Superior. They have to State, that it will be impossible for them to reach that place as the American Fur Co. are the only Co. who have vessels on Lake Superior & Notwithstanding they could procure on Passage Gratis on the Lake.

This distance between Sault Ste Mary, and the Mississippi is great and expensive. They also represent that the half Breeds born on Lake Superior are not entitled to any Share of the money allowed.

Whereas if the Payment was made at the Falls of St. Croix, there would be Competition amongst traders, whereas in Lake Superior they can be done none. They humbly beseech that you will have Mercy on them and not allow them to be deprived by intrigue of the Sum due them. So Justly to go in other hands but the real owners.

Respectfully

your most obd’t Serv’t

Joseph Rolette

on behalf of the Chippewaw

Half Breeds of

Prairie du Chiens

June 21, 1839

from the Indian Agent at Saint Peters

via the Governor of Wisconsin Territory

to the Superintendent of Indian Affairs

Received July 16, 1839

Answered July 24, 1839

Superintendency of Indn Affairs

for the Territory of Wisconsin

Mineral Point June 20, 1839

Sir,

Henry Dodge

Governor of Wisconsin Territory

I have the honor to transmit, enclosed herewith, three letters from Major Taliaferro, Indian Agent at St Peters, dated 10th, 16th, & 17th inst, with two Indian talks of 3rd & 14th, for the information of the Department.

Very respectfully

Yours obedt sevt

Henry Dodge

Supt Ind Agy

T Hartley Crawford Esq

Com. of Indian Affairs

North Western Agency St Peters

Upper Mississippi June 10th 1839

Governor,

Lawrence Taliaferro

Indian Agent at Fort Snelling

I deem it to be most adviseable that the enclosed paper, addressed to the Agent, and Commanding Officer on this Station from the Chippewa Chief “Hole in the Day” should be forwarded to you, the Indians addressing us being within your Excellency’s Superintendency. It may be well to add that a similar document proceeding from the Chippewa Chiefs of St Croix was on the 4th inst forwarded for the information of the Office of Indian Affairs at Washington.

The consolidation of the two Chippewa Sub Agencies and located at Lapointe, it is feared may lead to rather unpleasant results. I know the Chippewas well, and may have as much influence with those of the Mississippi particularly as most men, yet were I to say “you are not to have an agent in your Country, and you must go to Lapointe in all time to come for your Annuity, and treaty Stipulations.” I should not expect to hold their confidence for one day.

With high respect Sir

Your mo obt Serv

Law Taliaferro

Indian Agent

at S. Peters

His Excellency

Governor Henry Dodge

Suprt of Indi Affairs

at Mineral Point

For Wisconsin

North Western Agency S. Peters

Upper Mississippi June 16th, 1839

Governor

I have been earnestly selected by a number of the respectable half breed Chippewas resident, and others of the Mississippi, interested in the $100,000 set apart in the treaty of July 29, 1837 of S. Peters, to ask for such information as to their final disposal of this Sum, as may be in your possession.

The claimants referred to have learned through the medium of an unofficial letter from the Hon Lucius Lyon to H. H. Sibley Esqr. of this Post, that the funds in question as well as the Debts of the Chippewas to the traders was to be distributed by him as the Commissioner of the United States at Lapointe on Lake Superior, and for this purpose should reach that place on or about the 10th of July. The individuals Seeking this information are those who were were so greatly instrumental in bungling your labours at the treaty aforesaid to a successful issue in opposition to the combinations formed to defeat the objects of the government.

There remains 56,000$ in specie at this post being the one half of the sum appropriated or applicable to the objects in contemplation, and upon which the authorities here have had as yet no official instructions to transfer some special information would relieve the minds of a miserably poor class of people and who fear the entire loss of their just claims.

With high respect, Sir

your mo obt Sevt

Law Taliaferro

Indn Agent

at S. Peters

His Excellency

Gov Henry Dodge

Suprt of Ind. Affairs

for Wisconsin

North Western Agency S. Peters

Upper Mississippi June 17th 1839

Governor

On the 20th of May past I dispatched Peter Quin Express to the Chippewas of the Upper Mississippi with a letter from Maj D. P. Bushnell agent for this tribe at Lapointe notifying the Indians, and half breeds that they would be paid at Lapointe hereafter, and at an earlier period than the last year. I informed you of the result of his mission on the 10th inst. enclosing at the same time the written sentiments of the principle Chief for his people. I now forward by Express a second communication from the Same Source received late last night. I would make a plain copy, but have not time. So the original is Sent.

In four days there will be a large body of Chippwas here, and they cannot be Stopped. There are now also 880 Sioux from remote Sections of the Country at this Post and of course we may calculate on some difficulty between these old enemies. Your presence is deemed essential, or such instructions as may soothe the Angry feelings of the Chippewas, on account of the direction given to their annuity, & treaty Stipulations.

With high respect Sir

Your mo ob Sevt

Law Taliaferro

Indn Agent

at S Peters

His Excellency

Governor Henry Dodge

Suprt of Indi Affairs

Mineral Point

(NB) The Chippewas are to be understood as to the point of payment indicated to be the St.Croix, and not the S.Peters, as deemed by the written Talks. It never could be admited in the present state of the Tribes to pay the Chippewas at this Post, but they might with safety to all parties be paid at or above the Falls of S.Croix, by an agent who they ought to have or some special person assigned to this duty.

Elk River, June 3rd 1839

Maj Toliver. Maj Plimpton.

My respects to you both, and my hand: I am to let you know that I intend to pay you a visit, with my chiefs as braves, the principle of my warriors are verry anxious to pay you a visit.

The above mentioned men are verry anxious to see Gov. Dodge with whom we made the treaty, that we may have a talk with him. It was with him commissioner of the United-States we made the treaty, and we are verry much disappointed to hear the newes, we hear this day (IE that we must go to Lake Sup. for our pay) which we have this day decided we will not do; that we had rather die first: it is on this account we wish to pay you a visit, and have a talk with Gov. Dodge. You sir, Maj Toliver know verry well our situation, and that the distance is so great for us to go to Lake Sup. for to get our pay &c. or even a gun repaired; that it is inconsistent for such a thing to be required of us; even if we did literally place the matter in the hands of Government. We are all living yet that was present at the treaty when we ceded the land to the Unitedstates, and remember well what was our understanding in the agreement.

We now wish Maj Toliver; to mention to your children that it is a fals report that we had any intention to have more difficulty with the Sioux, as our Missionaries can attest as far as they understand us. We will be at the Fort in seventeen days to pay you a friendly visit as soon as we received the news; we sent expressed to our brethren to meet us at the mouth of Rum Riv. and accompany us to the Fort.

It is my desire that Maj Plimpton would keep fast hold of the money appropriated for my children the half breeds, in this section, and not let it go to Lake Sup. as they are like ourselves and it would cost them a great deal to go there for it.

Pah-ko-ne-ge-zeck or Hole in the Day

Maj Toliver

Maj Plimpton

Elk River June 14 1839

Maj L. Toliphero,

My hand, It is twelve dayes since we have the newes and are all qouiet yet. My father I shall not forget what was promiced us below, I think of what you promiced us when you were buing our lands.

My father this is the thing that you & we me to take care of when you bougt our lands & I remember all that you said to me. My father I am the cheif of all the Indians that sold there land and this is the time when all of your children are coming down to receive their payment where you promiced to pay us.

My father I am the cheif and hold the paper containing the promices that you made us. The Gov. D. promised us that in one year from the date of the treaty that we should receive our first payment and so continue anually.

My father; I have done for manny years what the white men have told me and have done well, and now I must look before we are to know what I have to do.

When I buy anything I pay immediately the Great Spirit knows this Now when we get below we are expecting all that you promiced us Ministers and Black Smiths and cattle.

I say my father that we want our payment at St Peters where you promiced us. I said that I wanted the half breeds to be payed there with us. I told you that when the half breeds were payed that there was some French that should have something ((ie) of the half breed money) because they had lived with us for many years and allways gave us some thing to eat when we went to their houses.

My father all of your children are displeased because you are to pay us in another place and not at St Peters it is to hard and far for us to be payed at Lapointe.

My father I did not know that the payment was to be made at Lapointe until we heard by Mr Quin.

My father it is so far to Lapointe that we should lose all of our children before we could get their and if we should brake our Gun we may throw it in the water for we cannot go there to get it mended, and if we have a [illegible] holding a coppy of the Treaty in his hand

Black Smith we want him here and not at Lapoint.

My father I want that you should tell me who it was told you that we all wanted our payment at Lapoint. All of the Cheifs are alive that hear what you said to us below. You Mr Toliphero hear me ask Gov Do’ for an Agen and to have him located here and he promiced that it should be so. I want that the Agent should be here because our enemies come here sometimes and if he was here perhaps they would not come. My father we are all of us very sorry that we did not ask you to come and be our Agent. I don’t know who made all of the nois about our being payed at Lapoint. I don’t look above where we should all starve for our payment but below where the Treaty was made.

My father give my compliments to all of the officers at the Fort.

Hole in The Day X

Maj L Toliphereo

1842 Treaty Speeches at La Pointe in the News

May 15, 2024

Collected by Amorin Mello & edited by Leo Filipczak

Robert Stuart was a top official in Astor’s American Fur Company in the upper Great Lakes region. Apparently, it was not a conflict of interest for him to also be U.S. Commissioner for a treaty in which the Fur Company would be a major beneficiary.

A gentleman who has recently returned from a visit to the Lake Superior Indian country, has furnished us with the particulars of a Treaty lately negotiated at La Pointe, during his sojourn at that place, by ROBERT STUART, Esq., Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the district of Michigan, on the part of the United States, and by the Chiefs and Braves of the Chippeway Indian nation on their own behalf and their people. From 3 to 4000 Indians were present, and the scene presented an imposing appearance. The object of the Government was the purchase of the Chippeway country for its valuable minerals, and to adopt a policy which is practised by Great Britain, i.e. of keeping intercourse with these powerful neighbors from year to year by paying them annuities and cultivating their friendship. It is a peculiar trait in the Indian character of being very punctual in regard to the fulfillment of any contract into which they enter, and much dissatisfaction has arisen among the different tribes toward our Government, in consequence of not complying strictly to the obligations on their part to the Indians, in the time of making the payments, for they are not generally paid until after the time stipulated in the treaty, and which has too often proven to be the means of losing their confidence and friendship.

On the 30th of September last, Mr. Stuart opened the Council, standing himself and some of his friends under an awning prepared for the occasion, and the vast assembly of the warlike Chippeways occupying seats which were arranged for their accommodation. A keg of Tobacco was rolled out and opened as a present to the Indians, and was distributed among them; when Mr. Stuart addressed them as follows:-

The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was a metaphor for infinite abundance in 1842. In less than 75 years, the species would be extinct. What that means for Stuart’s metaphor is hard to say (Biodiversity Heritage Library).

The chiefs who had been to Washington were the St. Croix chiefs Noodin (pictured below) and Bizhiki. They were brought to the capital as part of a multi-tribal delegation in 1824, which among other things, toured American military facilities.I am very glad to meet and shake hands with so many of my old friends in good health; last winter I visited your Great Father in Washington, and talked with him about you. He knows you are poor and have but little for your women and children, and that your lands are poor. He pities your condition, and has sent me here to see what can be done for you; some of your Bands get money, goods, and provisions by former Treaty, others get none because the Great Council at Washington did not think your lands worth purchasing. By the treaty you made with Gov. Cass, several years ago, you gave to your lands all the minerals; so the minerals belong no longer to you, and the white men are asking him permission to take the minerals from the land. But your Great Father wishes to pay you something for your lands and minerals before he will allow it. He knows you are needy and can be made comfortable with goods, provisions, and tobacco, some Farmers, Carpenters to aid in building your houses, and Blacksmiths to mend your guns, traps, &c., and something for schools to learn your children to read and write, and not grow up in ignorance. I hear you have been unpleased about your Farmers and Blacksmiths. If there is anything wrong I wish you would tell me, and I will write all your complaints to your Great Father, who is ever watchful over your welfare. I fear you do not esteem your teachers who come among you, and the schools which are among you, as you ought. Some of you seem to think you can learn as formerly, but do you not see that the Great Spirit is changing things all around you. Once the whole land was owned by you and other Indian Nations. Now the white men have almost the whole country, and they are as numerous as the Pigeons in the spring. You who have been in Washington know this; but the poor Indians are dying off with the use of whiskey, while others are sent off across the Mississippi to make room for the white men. Not because the Great Spirit loves the white men more than the Indians, but because the white men are wise and send their children to school and attend to instructions, so as to know more than you do. They become wise and rich while you are poor and ignorant, but if you send your children to school they may become wise like the white men; they will also learn to worship the Great Spirit like the whites, and enjoy the prosperity they enjoy. I hope, and he, that you will open your ears and hearts to receive this advice, and you will soon get great light. But said he, I am afraid of you, I see but few of you go to listen to the Missionaries, who are now preaching here every night; they are anxious that you should hear the word of the Great Spirit and learn to be happy and wise, and to have peace among yourselves.

The 1837 Treaty of St. Peters was mostly negotiated by Maajigaabaw or “La Trappe” of Leech Lake and other chiefs from outside the territory ceded by that treaty. The chiefs from the ceded lands were given relatively few opportunities to speak. This created animosity between the Lake Superior and Mississippi Bands.Your Great Father is very sorry to learn that there are divisions among his red children. You cannot be happy in this way. Your Great Father hopes you will live in peace together, and not do wrong to your white neighbors, so that no reports will be made against you, or pay demanded for damages done by you. These things when they occur displease him very much, and I myself am ashamed of such things when I hear them. Your Great Father is determined to put a stop to them, and he looks that the Chiefs and Braves will help him, so that all the wicked may be brought to justice; then you can hold up your heads, and your Great Father will be proud of you. Can I tell him that he can depend upon his Chippeway children acting in this way.

One other thing, your Great Father is grieved that you drink whiskey, for it makes you sick, poor, and miserable, and takes away your senses. He is determined to punish those men who bring whiskey among you, and of this I will talk more at another time.

Stuart would become irritated after the treaty when the Ojibwe argued they did not cede Isle Royale in 1842. This lead to further negotiations and an addendum in 1844. The Grand Portage Band, who lived closest to Isle Royale, was not party to the 1842 negotiations.When I was in New York about three moons ago I found 800 blankets which were due you last year, which by some mismanagement you did not get. Your Great Father was very angry about it, and wished me to bring them to you, and they will be given you at the payment. He is determined to see that you shall have justice done you, and to dismiss all improper agents. He despises all who would do you wrong. Now I propose to buy your lands from Fond du Lac, at the head of Lake Superior, down Lake Superior to Chocolate River near Grand Island, including all the Islands in the limits of the United States, in the Lake, making the boundary on Lake Superior about 250 miles in extent, and extending back into the country on Lake Superior about 100 miles. Mr. Stuart showed the Chiefs the boundary on the map, and said you must not suppose that your Great Father is very anxious to buy your lands, the principal object is the minerals, as the white people will not want to make homes upon them. Until the lands are wanted you will be permitted to live upon them as you now do. They may be wanted hereafter, and in this event your Great Father does not wish to leave you without a home. I propose that the Fond du Lac lands and the Sandy Lake tract (which embrace a tract 150 miles long by 100 miles deep) be left you for a home for all the bands, as only a small part of the Fond du Lac lands are to be included in the present purchase. Think well on the subject and counsel among yourselves, but allow no black birds to disturb you, your Great Father is now willing and can do you great good if you will, but if not you must take the consequences. To-morrow at the fire of the gun you can come to the Council ground and tell me whether the proposal I make in the name of your Great Father is agreeable to you; if so I will do what I can for you, you have known me to be your friend for many years. I would not do you wrong if I could, but desire to assist you if you allow me to do so. If you now refuse it will be long before you have another offer.

October 1st. At the sound of the Cannon the Council met, and when all were ready for business, Shingoop, the head Chief of the Fond du Lac band, with his 2d and 3d Chiefs, came forward and shook hands with the Commissioner and others associated with him, then spoke as follows:

Zhingob (Balsam), also known as Nindibens, signed the 1837, 1842, and 1854 treaties as chief or head chief of Fond du Lac. The Zhingob on earlier treaties is his father. See Ely, ed. Schenck, The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. ElyMy friend, we now know the purpose you came for and we don’t want to displease you. I am very glad there are so many Indians here to hear me. I wish to speak of the lands you want to buy of me. I don’t wish to displease the Traders. I don’t wish to displease the half-breeds; so I don’t wish to say at once, right off. I want to know what our Great Father will give us for them, then I will think and tell you what I think. You must not tell a lie, but tell us what our Great Father will give us for our lands. I want to ask you again, my Father. I want to see the writing, and who it is that gave our Great Father permission to take our minerals. I am well satisfied of what you said about Blacksmiths, Carpenters, Schools, Teachers, &c., as to what you said about whiskey, I cannot speak now. I do not know what the other Chiefs will say about it. I want to see the treaty and the name of the Chiefs who signed. The Chief answered that the Indians had been deceived, that they did not so understand it when they signed it.

Mr. Stuart replied that this was all talk for nothing, that the Government had a right to the minerals under former treaty, yet their Great Father wishes now to pay for the minerals and purchase their lands.

The Chief said he was satisfied. All shook hands again and the Chief retired.

The next Chief who came forward was the “Great Buffalo” Chief of the La Pointe band. Had heavy epaulettes on his shoulders and a hat trimmed with tinsel, with a heavy string of bear claws about his neck, and said:-

“Big Buffalo (Chippewa),” 1832-33 by Henry Inman, after J.O. Lewis (Smithsonian).

My father, I don’t speak for myself only, but for my Chiefs. What you said here yesterday when you called us your children, is what I speak about. I shall not say what the other Chief has said, that you have heard already.

He then made some remarks about the Missionaries who were laboring in their country and thought as yet, little had been done. About the Carpenters, he said, that he could not tell how it would work, as he had not tried it yet.

We have not decided yet about the Farmers, but we are pleased at your proposal about Blacksmiths. Can it be supposed that we can complete our deliberations in one night. We will think on the subject and decide as soon as we can.

The great Antonaugen Chief came next, observing the usual ceremony of shaking hands, and surrounded by his inferior Chiefs, said:-

The great Ontonagon Chief is almost certainly Okandikan (Buoy), depicted here in a reproduction of an 1848 pictograph carried to Washington and reproduced by Seth Eastman. Okandikan is depicted as his totem symbol, the eagle (largest, with wing extended in the center of the image).

My father and all the people listen and I call upon my Great Father in Heaven to bear witness to the rectitude of my intentions. It is now five years since we have listened to the Missionaries, yet I feel that we are but children as to our abilities. I will speak about the lands of our band, and wish to say what is just and honorable in relation to the subject. You said we are your children. We feel that we are still, most of us, in darkness, not able fully to comprehend all things on account of our ignorance. What you said about our becoming enlightened I am much pleased; you have thrown light on the subject into my mind, and I have found much delight and pleasure thereby. We now understand your proposition from our Great Father the President, and will now wait to hear what our Great Father will give us for our lands, then we will answer. This is for the Antannogens and Ance bands.

Mr. Stuart now said, that he came to treat with the whole Chippeway Nation and look upon them all as one Nation, and said

I am much pleased with those who have spoken; they are very fine orators; the only difficulty is, they do not seem to know whether they will sell their lands. If they have not made up their minds, we will put off the Council.

Lac du Flambeau Chief, “the Great Crow,” came forward with the strict Indian formalities but had but little to say, as he did not come expecting to have any part in the treaty, but wished to receive his payment and go home.

The 2d Chief of this band wished to speak. He was painted red with black spots on each cheek to set off his beauty, his forehead was painted blue, and when he came to speak, he said:-

What the last Chief has said is all I have to say. We will wait to hear what your proposals are and will answer at a proper time.

Next came forward “Noden,” or the “Great Wind,” Chief of the Mill Lac band, and said:-

Noodin (Wind) is mentioned here as representing the Mille Lacs Band, though his village was usually on Snake River of the St. Croix.

I have talked with my Great Father in Washington. It was a pity that I did not speak at the St. Peters treaty. My father, you said you had come to do justice. We do not wish to do injustice to our relations, the half-breeds, who are also our friends. I have a family and am in a hurry to get home, if my canoes get destroyed I shall have to go on foot. My father, I am hurry, I came for my payment. We have left our wives and children and they are impatient to have us return. We come a great distance and wish to do our business as soon as we can. I hope you will be as upright as our former agent. I am sorry not to see him seated with you. I fear it will not go as well as it would. I am hurry.

Mr Stuart now said that he considered them all one nation, and he wished to know whether they wished to sell their lands; until they gave this answer he could do nothing, and as it regards any thing further he could say nothing, and said they might now go away until Monday, at the firing of the Cannon they might come and tell him whether they would sell their country to their Great Father.

We intend giving the remainder of the proceedings of the treaty in our next.

Green Bay Republican:

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 1842, Page 2.

(Treaty with the Chippeways Concluded.)

Monday morning three guns were fired as a signal to open the Treaty. When all things were in readiness, Mr. Stuart said:

I am glad you have now had time for reflection, and I hope you are now ready like a band of brothers to answer the question which I have proposed. I want to see the Nation of one heart and of one mind.

Shingoop, Chief of the Fond du Lac band, came forward with full Indian ceremony, supported on each side by the inferior Chiefs. He addressed the Chippeway nation first, which was not fully interpreted; then he turned to the Commissioner and said:

in this Treaty which we are about to make, it is in my heart to say that I want our friends the traders, who have us in charge provided for. We want to provide also for our friends the half-breeds – we wish to state these preliminaries. Now we will talk of what you will give us for our country. There is a kind of justice to be done towards the traders and half-breeds. If you will do justice to us, we are ready to-morrow to sign the treaty and give up our lands. The 2d Chief of the band remarked, that he considered it the understanding that the half-breeds and traders were to be provided for.

The Great Buffalo, of La Pointe band, and his associate Chiefs came next, and the Buffalo said:

My Father, I want you to listen to what I say. You have heard what one Chief has said. I wish to say I am hurry on account of keeping so many men and women here away from their homes in this late season of the year, so I will say my answer is in the affirmative of your request; this is the mind of my Chiefs and braves and young men. I believe you are a correct man and have a heart to do justice, as you are sent here by our Great Father, the President. Father, our traders are so related to us that we cannot pass a winter without them. I want justice to be done them. I want you and our Great Father to assist us in doing them justice, likewise our half-breed children – the children of our daughters we wish provided for. It seems to me I can see your heart, and you are inclined to do so. We now come to the point for ourselves. We wish to know what you will give us for our country. Tell us, then we will advise with our friends. A part of the Antaunogens band are with me, the other part are turned Christians and gone with the Methodist band, (meaning the Ance band at Kewawanon) these are agreed in what I say.

The Bird, Chief of the Ance band, called Penasha, came forward in the usual form and said:

My Father, now listen to what I have to say. I agree with those who have spoken as far as our lands are concerned. What they say about our traders and half-breeds, I say the same. I speak for my band, they make use of my tongue to say what they would say and to express their minds. My Father, we listen to what you will offer for our country, then we will say what we have to say. We are ready to sell our country if your proposals are agreeable. All shook hands – equal dignity was maintained on each side – there was no inclination of the head or removing the hat – the Chiefs took their seats.

The White Crow next appeared to speak to the Great Father, and said:-

White Crow is apparently unaware that in the eyes of the United States, his lands, (Lac du Flambeau) were already sold five years earlier at St. Peters. Clearly, the notion of buying and selling land was not understood by him in the same way it was understood by Stuart.

Listen to what I say. I speak to the Great Father, to the Chiefs, Traders, and Half-breeds. You told us there was no deceit in what you say. You may think I am troublesome, but the way the treaty was made at St. Peters, we think was wrong. We want nothing of the kind again. We think you are a just man. You have listened to those Chiefs who live on Lake Superior. What I say is for another portion of country. It appears you are not anxious to buy the lands where I live, but you prefer the mineral country. I speak for the half-breeds, that they may be provided for: they have eaten out of the same dish with us: they are the children of our sisters and daughters. You may think there is something wrong in what I say. As to the traders, I am not the same mind with some. The old traders many years ago, charged us high and ought to pay us back, instead of bringing us in debt. I do not wish to provide for them; but of late years they have had looses and I wish those late debts to be paid. We do not consider that we sell our lands by saying we will sell them, so we consent to sell if your proposals are agreeable. We will listen and hear what they are.

Several others of the Chiefs spoke well on the subject, but the substance of all is contained in the above.

Hole-in-the-day, who is at once an orator and warrior, came forward; he had an Arkansas tooth pick in his hand which would weigh one or two pounds, and is evidently the greatest and most intelligent man in the nation, as fine a form of body, head and face, as perhaps could be found in any country.

Father, said he, I arise to speak. I have listened with pleasure to your proposal. I have come to tie the knot. I have come to finish this part of the treaty, and consent to sell our country if the offers of the President please us. Then addressing the Chiefs of the several bands he said, the knot is now tied, and so far the treaty is complete, not to be changed.

Zhaagobe (“Little” Six) signed as first chief from Snake River, and he is almost certainly the “Big Six” mentioned here. Several Ojibwe and Dakota chiefs from that region used that name (sometimes rendered in Dakota as Shakopee).

Big Six now addressed the whole Nation in a stream of eloquence which called down thunders of applause; he stands next to Hole-in-the-day in consequence and influence in the nation. His motions were graceful, his enunciation rather rapid for a fine speaker. He evidently possesses a good mind, though in person and form he is quite inferior to Hole-in-the-day. His speech was not interpreted, but was said to be in favor of selling the Chippeway country if the offer of the Government should meet their expectations, and that he took a most enlightened view of the happiness which the nation would enjoy if they would live in peace together and attend to good counsel.

Mr. Stuart now said,

I am very happy that the Chippewa nation are all of one mind. It is my great desire that they should continue to for it is the only way for them to be happy and wise. I was afraid our “White Crow” was going to fly away, but am happy to see him come back to the flock, so that you are all now like one man. Nothing can give me greater pleasure than to do all for you I can, as far as my instructions from your Great Father will allow me. I am sorry you had any cause to complain of the treaty at St. Peters. I don’t believe the Commissioner intended to do you wrong, but perhaps he did not know your wants and circumstances so as to suit. But in making this treaty we will try to reconcile all differences and make all right. I will now proceed to offer you all I can give you for your country at once. You must not expect me to alter it, I think you will be pleased with the offer. If some small things do not suit you, you can pass them over. The proposal I now make is better than the Government has given any other nation of Indians for their lands, when their situations are considered. Almost double the amount paid to the Mackinaw Indians for their good lands. I offer more than I at first intended as I find there are so many of you, and because I see you are so friendly to our Government, and on account of your kind feelings for the traders and half-breeds, and because you wish to comply with the wishes of your Great Father, and because I wish to unite you all together. At first I thought of making your annuities for only twenty years but I will make them twenty-five years. For twenty-five years I will offer you the following and some items for one year only.

$12,500 in specie each year for 25 years, $312,500

10,500 in goods ” ” ” ” ” 262,500

2,000 in provisions and tobacco, do. 50,000$625,000

This amount will be connected with the annuity paid to a part of the bands on the St. Peters treaty, and the whole amount of both treaties will be equally distributed to all the bands so as to make but one payment of the whole, so that you will be but one nation, like one happy family, and I hope there will be no bad heart to wish it otherwise. This is in a manner what you are to get for your lands, but your Great Father and the great Council at Washington are still willing to do more for you as I will now name, which you will consider as a kind of present to you, viz:

2 Blacksmiths, 25 years, $2000, $50,000

2 Farmers, ” ” 1200, 30,000

2 Carpenters, ” ” 1200, 30,000

For Schools, ” ” 2000, 50,000

For Plows, Glass, Nails, &c. for one year only, 5000

For Credits for one year only, 75,000

For Half-breeds ” ” ” 15,000$255,000

Total $880,000

With regards to the claims. I will not allow any claim previous to 1822; none which I deem unjust or improper. I will endeavor to do you justice, and if the $75,000 is not all required to pay your honest debts, the balance shall be paid to you; and if but a part of your debts are paid your Great Father requires a receipt in full, and I hope you will not get any more credits hereafter. I hope you have wisdom enough to see that this is a good offer. The white people do not want to settle on the lands now and perhaps never will, so you will enjoy your lands and annuities at the same time. My proposal is now before you.

The Fond du Lac Chief said, we will come to-morrow and give our answer.

October 4th, Mr. Stuart opened the Council.

Clement Hudon Beaulieu, was about thirty at this time and working his way up through the ranks of the American Fur Company at the beginning of what would be a long and lucrative career as an Ojibwe trader. His influence would have been very useful to Stuart as he was a close relative of Chief Gichi-Waabizheshi. He may have also been related to the Lac du Flambeau chiefs–though probably not a grandson of White Crow as some online sources suggest.

We have now met said he, under a clear sun, and I hope all darkness will be driven away. i hope there is not a half-breed whose heart is bad enough to prevent the treaty, no half-breed would prevent he treaty unless he is either bad at heart or a fool. But some people are so greedy that they are never satisfied. I am happy to see that there is one half-breed (meaning Mr. Clermont Bolio) who has heart enough to advise what is good; it is because he has a good heart, and is willing to work for his living and not sponge it out of the Indians.

We now heard the yells and war whoops of about one hundred warriors, ornamented and painted in a most fantastic manner, jumping and dancing, attended with the wild music usual in war excursions. They came on to the Council ground and arrested for a time the proceedings. These braves were opposed to the treaty, and had now come fully determined to stop the treaty and prevent the Chiefs from signing it. They were armed with spears, knives, bows and arrows, and had a feather flag flying over ten feet long. When they were brought to silence, Mr. Stuart addressed them appropriately and they soon became quiet, so that the business of the treaty proceeded. Several Chiefs spoke by way of protecting themselves from injustice, and then all set down and listened to the treaty, and Mr. Stuart said he hoped they would understand it so as to have no complaints to make afterwards.

The provisions of the treaty are the same as made in the proposals as to the amount and the manner of payment. The Indians are to live on the lands until they are wanted by the Government. They reserve a tract called the Fond du Lac and Sandy Lake country, and the lands purchased are those already named in the proposals. The payment on this treaty and that of the St. Peters treaty are to be united, and equal payments made to all the bands and families included in both treaties. This was done to unite the nation together. All will receive payments alike. The treaty was to be binding when signed by the President and the great Council at Washington. All the Chiefs signed the treaty, the name of Hole-in-the-day standing at the head of the list, and it is said to be the greatest price paid for Indian lands by the United States, their situation considered, though the minerals are said to be very valuable.

The Commissioner is said to have conducted the treaty in a very just, impartial and honorable manner, and the Indians expressed the kindest feelings towards him, and the greatest respect for all associated with him in negotiating the treaty and the best feelings towards their Agent now about leaving the country, and for the Agents of the American Fur Company and for the traders. The most of them expressed the warmest kind of feelings toward the Missionaries, who had come to their country to instruct them out of the word of the Great Spirit. The weather was very pleasant, and the scene presented was very interesting.

Among The Otchipwees: II

June 4, 2016

By Amorin Mello

… continued from Among The Otchipwees: I

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 3 January 1885

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 177-192.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

II.

In the fall of 1849, the Bad Water band were in excellent condition, and therefore very happy. Deer were then very abundant on the Menominee. They are nimble animals, able to leap gracefully over obstructions as high as a man’s head standing. But they do not like such efforts, unless there is a necessity for it. The Indians discovered this long ago, and built long brush fences across their trails to the water. When the unsuspecting animal has finished browsing, he goes for a drink with the regularity of an habitué of a saloon. Seeing the obstruction, he walks leisurely along it, expecting to find a low place, or the end of it. The dark eye of the Chippewa is fixed upon him from the top of a tree. This is much the best position, because the deer is not likely to look up, and the wind is less likely to bear his odor to the delicate nostrils of the game. At such close quarters every shot is fatal. Its throat is cut, its legs tied together, and thrown over the head and shoulders of the hunter, its body resting on his back, and he starts for the village. Here the squaws strip off the hide and prepare the carcass for the kettle. With a tin cup full of flour or a pound of pork, we often purchased a saddle of venison, and both parties were satisfied with the trade.

Naagaanab

~ Minnesota Historical Society

~ Executive Documents of the State of Minnesota for the Year 1886, Volume V.: Minnesota Geographical Names Derived from the Chippewa Language, by Reverend Joseph Alexander Gilfillan, 1887, page 457.

“Akwaakwaa” refers to “go a certain distance in the woods.”

~ General Geology: Miscellaneous Papers, Volume 1: A Report of Explorations in the Mineral Regions of Minnesota During the Years 1848, 1859 and 1864 by Colonel Charles Whittlesey, 1866, page 44.

Of course the man of the woods has a preference as to what he shall eat; but when he is suffering from hunger, as he is a large part of his days, he is not very particular. Fresh venison, bear meat, buffalo, moose, caribou, porcupine, wild geese, ducks, rabbits, pigeons, or fish, relish better than gulls, foxes, or skunks. The latter do very well while he is on the verge of starvation, and even owls, crows, dead horses and oxen. The lakes of the interior of Minnesota and Wisconsin produce wild rice spontaneously. When parched it is more palatable than southern rice, and more nutritious. Potatoes grow well everywhere in the north country; varieties of corn ripen as far north as Red Lake. Nothing but a disinclination to labor hinders the Chippewa from always having enough to eat. With the wild rice, sugar, and the fat of animals, well mixed, they make excellent rations, which will sustain life longer than any preparation known to white men. A packer will carry on his back enough to last him forty days. He needs only a tin cup in which to warm water, with which it makes a rich soup. Pemmican is less palatable, and sooner becomes rancid. This is made of smoke or jerked meat pulverized, saturated with fat and pressed into cakes or blocks. Sturgeon are numerous and large, and when well smoked and well pulverized they furnish palatable food even without salt, and keep indefinitely. Voyagers mix it with sugar and water in their cups. In the large lakes, white fish, siskowit, and lake trout are abundant. In the smaller lakes and rivers there are many varieties of fish. With so many resources supplied by nature, if the natives suffer from hunger it is solely caused by indolence. His implicit reliance upon the Great Spirit, which is his good Providence, no doubt encourages improvidence. Nanganob was apparently very desirous to have a garden at Ashkebwaka, for which I sent him a barrel of seed potatoes, corn, pumpkins, and a general assortment of seeds. Precisely what was done with the parcel I do not know, but none of it went into the ground. In most cases everything eatable went into their stomachs as soon as they were hungry. Even after potatoes had been planted, they have been dug out and eaten, and squashes when they were merely out of bloom. If the master of a lodge should be inclined to preserve the seed and a hungry brother came that way, their hospitality required that the garden should be sacrificed. Their motto is that the morrow will take care of itself. After being well fed, they are especially worthless. When corn has been issued to them to carry to their home, they have been known to throw it away and go off as happy as children.

Detail of the Saint Louis River with the Artichoke River (unlabeled) between the Knife Portage and East Savannah River from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

No footgear is more comfortable, especially in winter, than the moccasin. The Indian knows nothing of cold feet, though he has no shoes or even socks. His light loose moccasin is large enough to allow a wrap of one or more thickness of pieces of blankets, called “nepes.” In times of extreme cold, wisps of hay are put in around the “nepes.” In winter the snow is dry, and the rivers and swamps everywhere covered with ice, which is a thorough protection against wet feet. As they are never pinched by the devices of shoemakers, the blood circulates freely. The well tanned deer skin is soft and a good nonconductor, which cannot be said of the footgear of civilization. In summer the moccasin is light and easy to the foot, but is no protection against water. At night it is not dried at the camp-fire only wrung out to be put on wet in the morning. Like the bow and the arrow, these have nearly disappeared since Europeans have furnished bullets, powder and guns. Before that time the war club was a very important weapon. It was of wood, having a strong handle, with a ball or knot at the end. If the Chippewas used battleaxes of stone, they could not have been common. I have rarely seen a light war club with an iron spike well fastened in the knot or ball at the end. In ancient days, when their arrows and daggers were tipped with flint, their battles were like those of all rude people – personal encounters of the most desperate character. The sick are possessed of evil spirits which are driven out by incantations loud and prolonged enough to kill a well person. Their acquaintance with medical herbs is very complete.

One of the customs of the country is that of concubinage as well as polygamy, resembling in this respect the ancient Hebrews and other Eastern nations. The parents of a girl – on proper application and the payment of a blanket, some tobacco and other et ceteras, amounting to “ten pieces” – bestowing their daughter for such a period as her new master may choose. A further consideration is understood that she is to be clothed and fed, and when the parents visit the traders’ post they expect some pork and flour. To a maiden – who, as an Indian wife or in her father’s house is not only a drudge but a slave, compelled to row the canoe, to cut and bring wood, put up the lodge and take it down, and always to carry some burden – this situation is a very agreeable one. If she wishes to marry afterwards, her reputation does not suffer. While Mr. B. was conversing with the Hudson’s Bay man on the bank, some of the girls came coquettishly down to them frisking about in their rabbit skin blankets well saturated with grease. One of them managed to keep in view what she considered a special attraction – a fine pewter ring on her finger. These Chippewas damsels had in some way acquired the art of insinuation belonging to the sex without the aid of a boarding school.

The Indian agent at La Pointe killed a deer of about medium size, which he left in the woods. He engaged an Indian to bring it in. Night came and the next day before the man returned without the deer. “Where is my deer?” “Eat him, don’t suppose me to eat nothing.” Probably that meal lasted him a week. There is among them no regular time for meals or other occupations. If there are provisions in the lodge, each one helps himself; and if a visitor comes, he is offered what he can eat as long as it lasts. This is their view of hospitality. The lazy and worthless are never refused. To do this to the meanest professional dead beat would be the ruin of the character of the host.

Detail of portage between Lake Vermillion and the Saint Louis River headwaters from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

“Vincent Roy Sr. was born at Leech Lake Minn. in the year 1779 1797, and died at Superior, Wis. Feb. 18th 1872. He was a son of a Canadian Frenchman by the same name as his son bears. When V. Roy, Sr was about 17 or 18 years old, they emigrated to Fort Frances, Dominion of Canada, where he was engaged by the North-West Fur Co. as a trader until the two Companies (the North-West and the Hudson Bay Co joined together) he still worked for the consolidated Company for 12 or 15 years. When the American Traders came out at the Vermillion Lake country in Minnesota Three or four years afterwards he joined the American Traders. For several years he went to Mackinaw, buying goods and supplies for the Bois Fortes bands of Chippeways on Rainy and Vermillion Lake Country. About the year 1839 he came out to the Lake Superior Country and located his family at La Pointe. In winters he went out to Leech Lake Minn., trading for the American Fur Co. For several years until in the year of 1847 when the Hon. H. M. Rice, now of St. Paul, came to this country representing the Pierre Choteau Co. as a fur trading company. V. Roy, Sr. engaged to Pierre Choteau & Co. to trade with his former Indians at Vermillion Lake Country for two years, and then went for the American Fur Company again for one year. After a few years he engaged as a trader again for Peter E. Bradshaw & Co. and went to Red Lake, Minn. for several years. In 1861 he went to Nipigon (on Canadian side) trading for the same company. In a few years, he again went back to his old post at Vermillion Lake, Minn., where he contracted a very severe sickness, in two years afterwards he died at Superior among his Children as stated before &c.”

~ Minnesota Historical Society: Henry M. Rice and Family Papers, 1824-1966; Box 4; Sketches folder; Item “Roy, Vincent, 1797-1872”

Among the Chippewas we hear of man eaters, from the earliest travelers down to this day. Mr. Bushnell, formerly Indian agent at La Pointe, described one whom he saw who belonged on the St. Louis River and Vermillion Lake. The Indians have a superstitious dread of them, and will flee when one enters the lodge. They are hated, but it is supposed they cannot be killed, and no one ventures to make the experiment. it is only by a bullet such as the man eater himself shall designate that his body can be pierced. He is frequently a lunatic, spending days and nights alone in the woods in mid winter without food, traveling long spaces to present himself unexpectedly among distant bands. Whatever he chooses to eat is left for him, and right glad are the inmates of a lodge to get rid of him on such easy terms. The practice is not acquired from choice, but from the terrible necessities of hunger which happen every winter among the northern Indians. Like shipwrecked parties at sea, the weaker first falls a prey to the stronger, and their flesh goes to sustain life a little longer among the remainder. The Chippewas think that after one has tasted human food he has an uncontrollable longing for it, and that it is not safe to leave children alone with them. They say a man eater has red eyes and he looks upon the fat papoose with a demonical glance, and says: “How tender he would be.” One miserable object on the St. Louis River eat off his own lips, and finally became such a source of consternation that one Indian more courageous than the rest buried a tomahawk in his head. Another one who had the reputation of having killed all of his own family, came to the winter fishing ground on Rainy Lake, where Mr. Roy was trading with the Indians. He stayed on the ice trying to take some fish, but without success. Not one of the band dared go out to fish, although they were suffering from hunger. Mr. Roy and all the Indians requested him to go away, but he would not unless he had something to eat. no one but the trader could give him anything, and he was not inclined to do so. Things remained thus during three days, no squaw daring to go on the ice to fish for fear of the man eater. Mr. Roy urged them to kill him, but they said it would be of no use to shoot at him. The man eater dared them to fire. The trader at length lost patience with the cannibal and the terrified Bois Forts. He took his gun and warned the fellow that he would be shot if he remained on the ice. The faith of the savage appears to have been strong in the charm that surrounded his person, for he only replied by a laugh of derision. On the other side Mr. Roy had great faith in his rifle, and discharging it at the body of the man, he fell dead, as might have been expected. The Indians were at once relieved of a dreadful load, and sallied out to fish. No one, however, dared to touch the corpse.

No one of either party can go into the country of the other, and not be discovered. Their moccasins differ and their mode of walking. Their canoes and paddles are not alike, and their camp-fires as well as their lodges differ. The Chippewa lodge or wigwam is made by a circular or oblong row of small poles set in the ground, bending the tops over and fastening them with bark. They carry everywhere rolls of birch bark, which unroll like a carpet. These are wound on the poles next the ground course, and overlapping this a second and third, so as to shed rain. On one side is a low opening covered by a blanket, and at the top a circular place for the smoke to escape. The fire is on the ground at the centre. The work of putting up the lodge is done by the squaws, who gather wood for the fire, spread the mats, and proceed to cook their meals, provided there is anything to cook.

Stereograph of “Chippewa Indians and Wigwams” by Martin’s Art Gallery, circa 1862-1875, shows that they used more than one type of wigwam.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

A Sioux lodge is the model of the Sibley tent, with a pole at the centre and others set around in a circle, leaning against the central one at the top, forming a cone. This they cover with skins of the buffalo, deer, elk or moose, wound around like the Chippewa rolls of bark, leaving a space at the top for the smoke to escape, and an entrance at the side. This is stronger and more compact than the Chippewa wigwam, and withstands the fiercest storms of the prairies. In winter, earth is occasionally piled around the base, which makes it firmer and warmer.

We were coming down the Rum River, late in the fall of 1848, when one of our voyageurs discovered the track of a Sioux in the sand. It was at least three weeks old, but nothing could induce him to stay with us, not even an hour. He was not sure but a mortal enemy was then tracking us for the purpose of killing him.

Detail of Red Lake from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

Earlier in the season we were at Red Lake. A cloud of smoke came up from the west, which caused a commotion in the village and mission at the south end of the lake. A war party was then out on a Sioux raid. The chief had lost a son, killed by them. He had managed to get the hand of a Sioux, which he had planted at the head of his son’s grave. But this did not satisfy his revenge nor appease the spirit of his son. He organized a war party to get more scalps, which was then out. A warrior chief or medicine man gains his principal control of the warriors by means of a prophecy, which he must make in detail. If the first of his predictions should fail, the party may desert him entirely. In this case, on a certain day they would meet a bear. When they met the enemy, if they were to be victorious, a cloud of smoke would obscure the sun. It was this darkening of the sky that excited the hopes of the Red Lake band. They were sure there had been a battle and that the Sioux were defeated.

Judge Samuel Ashmun

~ Chippewa County Historical Society

The late Judge Ashmun, of Sault Ste. Marie, while he was a minor, wandered off from his nativity in Vermont to Lake Superior, through it to Fond du Lac, and thence by way of the St. Louis River to Sandy Lake on the Mississippi. Somewhere in that region he was put in charge of one of Astor’s trading posts. In the early winter of 1818 he went on a hunt with a party of seventeen indiscreet young braves, against the advice of the sachems, apparently in a southwesterly direction on the Sioux border, or neutral land. Far from being neutral, it was very bloody ground. At the end of the third day they were about fifty miles from the post. On the morning of each day a rendezvous was fixed upon for the next camp. Each one then commenced the hunt for the day, taking what route pleased himself. The ice on the lakes and marshes was strong and the snow not uncomfortably deep. The principal game was deer, with some pheasants, prairie hens, rabbits and porcupines. What a hunter could not carry he hung upon trees to be carried home upon their return. Their last camp was on the border of a lake in thick woods, with tall dry grass on the margin of the lake. Having killed all the deer they could carry, it was determined to begin the return march the next day. It was not a war party, but they were prepared for their Sioux enemies, of whom no signs had been discerned. There was no whiskey in the camp, but when the stomach of an Indian is filled to its enormous capacity with fresh venison he is always jolly. It was too numerous a party to shelter themselves by a roof of boughs over the fire, but they had made a screen against the wind of branches of pine, hemlock or balsam. Around the fire was a circle of boughs on which they sat, ate and slept. Some were mending their moccasins, other smoking tobacco and kinnikinic, playing practical jokes, telling stories, singing songs and gambling. Mr. Ashmun could get so little sleep that he took Wa-ne-jo, who had a boy of thirteen years, and they made a separate camp. This man going to the lake to drink, was certain that he heard the tramp and felt the vibrations of a party going over the ice, who could be no other than the Sioux. He returned, and after some hesitation Mr. Ashmun reported the news to the main camp. “Oh, Wa-ne-jo is a liar, nobody believes him,” was the universal response. Mr. Ashmun, however, gave credit to the repot. They immediately put out the fire at his bivouac. Even war parties do not place sentinels, because attacks are never made until break of day. In the isolated camp they waited impatiently for the first glimpse of morning. Most of the other party fell asleep with a feeling of security, for which they took no steps to verify. One of them lay down without his moccasins. Mr. Ashmun and his man were just ready to jump for the tall grass when a volley was poured into the other camp, accompanied by the usual savage yell. The darkness and stillness of a faint morning twilight made this burst of war still more terrific. Taking the boy between them, they commenced the race for life under the guidance of Wa-ne-jo, in a direction directly opposite to their home. He well knew the Sioux all night long had been creeping stealthily over the snow and through the thicket, and had formed a line behind the main camp. The Chippewas made a brave defence, giving back their howls of defiance and fighting as they dispersed through the woods. Eight were killed near the camp and a wounded one at some distance, where he had secreted himself. Two fo the wounded were helped away according to custom, and also the barefooted man, whose feet were soon frozen. All clung to their guns, and the frightened boy to his hatchet. They estimated the Sioux party to have been one hundred and thirty, of whom they killed four and wounded seven, but brought in no scalps.

Indians Canoeing in the Rapids painting by Cornelius Krieghoff, 1856.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

In his way, the Chippewa is quite religious. He believes in a future world where there is a happy place for good Indians. If he is paddling his canoe against a head wind and can afford it, he throws overboard a piece of tobacco, the most precious thing he has. With this offering there is a short invocation to the good manitou for a fair breeze, when he can raise a blanket for a sail, stop rowing and take a smoke. At the head of many a rapid which it is dangerous to run, are seen pieces of tobacco on the rocks, which were laid there with a brief prayer that they may go safely through. Some of them, which are frightful to white men, they pass habitually. These offerings are never disturbed, for they are sacred. He endeavors also to appease the evil spirit Nonibojan. Fire, rocks, waterfalls, mountains and animals are alive with spirits good and bad. The medicine man, who is prophet, physician, priest and warrior, is an object of reverence and admiration. His prayers are for success in the hunt, accompanied by incantations.

George Bonga

~ Wikipedia.org

Among the stories of a thousand camp-fires, was one by Charlie, a stalwart, half-breed Indian and negro, whose father was an escaped slave. On the shores of Sandy Lake, a party of Chippewas had crossed on the ice in midwinter, and encamped in the woods not far from the north shore. One of them went to the Lake with a kettle of water, and a hatchet to cut the ice. After he filled his kettle, he lay down to drink. The water was not entirely quiet, which attracted his attention at once. His suspicions were aroused, and placing his ear to the ice, he discerned regular pulsations, which his wits, sharpened by close attention to every sight and every sound, interpreted to be the tramp of men. They could be no other than Sioux, and there must be a party larger than their own. Their fire was instantly put out, and they separated to meet at daylight at a place several miles distant. All their conclusions were right. One band of savages outwitted another, having instincts of danger that civilized men would have allowed to pass unnoticed. The Sioux found only the embers of a deserted camp, and saw the tracks of their enemies diverge in so many directions that it was useless to pursue.

In 1839 the Chippewas on the upper Mississippi were required to come to Fort Snelling to receive their payments. That post was in Sioux territory, and the order gave offense to both nations. It required the presence of the United States troops to prevent murders even on the reservation. On the way home at Sunrise River, the Chippewas were surprised by a large force of Sioux, and one hundred and thirty-six were killed.

At the mouth of Crow Wing River, on the east bank of the Mississippi, is a ridge of gravel, on which there were shallow pits. The Indians said that, about fifteen years before, a war party of Sioux was above there on the river to attack the Sandy Lake band. A party of Chippewas concealed themselves in these pits, awaiting the descent of their enemies. The affair was so well managed that the surprise was complete. When the uncautious Sioux floated along within close range of their guns, the Chippewa warriors rose and delivered their fire into the canoes. Some got ashore and escaped through the woods to the westward, but a large portion were killed.

Detail of Crow Wing River from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

While crossing the Elk River, between the falls of St. Anthony and those of St. Cloud, a squaw ran into the water, screaming furiously, followed by a man with a club. This was her lord and master, bent on giving her a taste of discipline very common in Indian life. She succeeded in escaping this time by going into deep water. Her nose had been disfigured by cutting away most of the fleshy portions, as a punishment for unfaithfulness to a husband, who was probably worse than herself.

At the mouth of Crow Wing River was an Indian skipping about with the skin of a skunk tied to one of his ankles. There was also in a camp near the post another Chippewa, who had murdered a brother of the lively man. There is no criminal law among them but that of retaliation. Any member of the family may execute this law at such time and manner as he shall decide. This badge of skunk’s skin was a notice to the murderer that the avenger was about, and that his mission was not fulfilled. Once the guilty man had been shot through the thigh, as a foretaste of what was to follow. The avenger seemed to enjoy badgering his enemy, whom he informed that although he might be occasionally wounded, it was not the intention at present to kill him outright. If the victim should kill his persecutor, he well knew that some other relative would have executed full retaliation.

~ The Assassination of Hole In The Day [the Younger] by Anton Treuer, 2010.

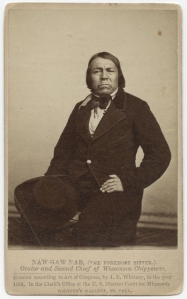

Hole In The Day the Younger

aka Kue-wee-sas (Gwiiwizens [Boy or Lad])

(1825-1868)

Bagone-giizhig the Younger

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

This Chippewa brave, Bug-on-a-ke-dit, lived on a knoll overlooking the Mississippi River, four miles above Little Rock, where he had a garden. He appeared at the payment at La Pointe, in 1848, with a breech cloth and scanty leggings. This was partially for showing off a very perfect figure, tall, round and lithe, the Apollo of the woods. His scanty dress enabled him to exhibit his trophies in war. The dried ears of his foes, a part of whom were women, were suspended at his neck. Around his tawny arms were bright brass bands, but there was nothing of which he was more proud than a bullet hole just below the right breast. The place of the wound was painted black, and around it circles of red, yellow and purple; other marks on the chest, arms and face told of the numbers he had slain and scalped, in characters well understood by all Chippewas. The numbers of eagle feathers in his hair informed the savage crowd how many battles he had fought. He was not, like Grizzly Bear, a great orator, but resembled him in getting drunk at every opportunity. He managed to procure a barrel of whiskey, which he carried to his lodge. While it was being unloaded it fell upon and crushed him to death. Looking up a grass clad hill, a dingy flag was seen (1848) fluttering on a pole where he was buried. He often repeated with great zest the mode by which the owners of two of the desecrated ears were killed. His party of four braves discovered some Sioux lodges on the St. Peters, from which all the men were absent. The squaws lodged their hereditary enemies over night with their accustomed hospitality. Bug-on-a-ke-dit and his party concealed themselves during the day, and at dark each one attacked a lodge. Seven women and children were slaughtered. His son Kue-wee-sas, or Po-go-noy-ke-schik, was a much more respectable and influential chief.

An hundred years since, the Sioux had an extensive burial ground, on the outlet of Sandy Lake, a few miles east of the Mississippi River. Their dead were encased in bark coffins and placed on scaffolds supported by four cedar posts, five or six feet high. This was done to prevent wolves from destroying the bodies. Thirty years since some of these coffins were standing in a perfect condition, but most of them were broken or wholly fallen, only the posts standing well whitened by age. The Chippewas wrap the corpse in a blanket and a roll of birch bark, and dig a shallow grave in which the dead are laid. A warrior is entitled to have his bow and arrow, sometimes a gun and and a kettle, laid beside him with his trinkets. Over the mound a roof of cedar bark is firmly set up, and the whole fenced with logs or protected in some way against wolves and other wild animals. There is a hole at one or both ends of the bark shelter, in which is friends place various kinds of food. Their belief in a spirit world hereafter is universal. If it is a hunter or warrior, he will need his arms to kill game or to slay his enemies. Their theory is that the dog may go to the spiritual country, as a spirit, also his weapons, and the food which is provided for the journey. To him every thing has its spiritual as well as its material existence. Over all is the great spirit or kitchi-manitou, looking after the happiness of his children here and hereafter.

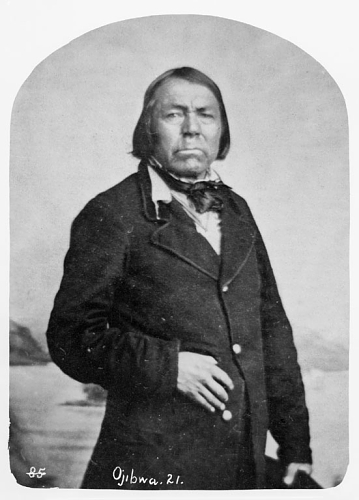

Stephen Bonga

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Winter travelling in those northern regions is by no means so uncomfortable as white men imagine. By means of snow shoes the Indian can move in a straight course towards his village, without regard to the trail. In the short days of winter he starts at day break and travels util dark. Stephen said he made fifty miles a day in that way, which is more than he could have done in summer.

At night they endeavor to find a thicket where there is a screen against the wind and plenty of wood. They scoop away the snow with their shoes and start a fire at the bottom of the pit. Around this they spread branches of pine, balsam or cedar, and over head make a shelter of brush to keep off the falling snow. Probably they have a team or more of dogs harnessed to sledges, who take their places around the fire. Here they cook and eat an enormous meal, when they wrap themselves in blankets for a profound sleep. Long before day another heavy meal is eaten. Everything is put in its proper package ready to start as soon as there is light enough to keep their course.

– Freelang Ojibwe-English by Weshki-ayaad, Charles Lippert and Guy T. Gambill

– Ojibwe People’s Dictionary by the Department of American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota

Many Indian words have originated since the white people came among them. A large proportion of their proper names are very apt expressions of something connected with the person, lake, river, or mountain to which they are applied. This people, in their primitive state, knew nothing of alcohol, coffee, tea, fire-arms, money, iron, and hundreds of other things to which they gave names, generally very appropriate ones. A negro is black meat; coffee is black medicine drink; tea, red medicine drink; iron, black metal; gold, yellow metal. I was taking the altitude of the sun at noon near Red Lake Mission with a crowd of Chippewas standing around greatly interested. They had not seen the liquid metal mercury, used for an artificial horizon in such observations, which excited their especial astonishment, and they had no name for it. One of them said something which caused a general expression of delight, for which I enquired the reason. He had coined a word for mercury on the spot, which means silver water.

Detail of Minnesota Point during George Stuntz’s survey contract during August-October of 1852.

~ Barber Papers (prologue): Stuntz Surveys Superior City 1852-1854

This family’s sugar bush was located at or near Silver Creek (T53N-R10W).

~ General Land Office Records

Indian trail to Rockland townsite overlooking English/Mineral Lake and Gogebic Iron Range.

~ Penokee Survey Incidents: Number V

Coasting along the beach northward from the mouth of the St. Louis River, on Minnesota Point, I saw a remarkable mark in the sand and went ashore to examine it. The heel and after part was clearly human. At the toes there was a cleft like the letter V and on each side some had one, others two human toes. Not far distant were Indians picking berries under the pine trees, which then covered the point in its entire length. We asked the berrypickers what made those tracks. They smiled and offered to sell us berries, of which they had several bushels, some in mokoks of birch bark, others in their greasy blankets. An old man had taken off his shirt, tied the neck and arms, and filled it half full of huckleberries. By purchasing some, (not from the shirt or blanket) we obtained an explanation of the nondescript tracks. There was a large family, all girls, whose feet were deformed in that manner. It was as though their feet had been split open when young halfway to the instep, and some of the toes lost. They had that spring met with a great loss by the remorseless bear. On the north shore, thirty miles east of Duluth, they had a fine sugar orchard, and had made an unusual quantity of sugar. A part was brought away, and a part was stored high up in trees in mokoks. There is nothing more tempting than sugar and whiskey to a bear. When this hard working family returned for their sugar and dried apples, moistened with whiskey, to lure bruin on to his ruin. A trap fixed with a heavy log is set up across a pen of logs, in the back end of which this bait is left, very firmly tied between two pieces of wood. This is fastened to a wooden deadfall, supporting one end of a long piece of round timber that has another piece under it. The bear smells the bait from afar, goes recklessly into the pen, and commences to gnaw the pieces of wood; before he gets much of the bait the upper log falls across his back, crushing him upon the lower one, where, if he is not killed, his hind legs are paralyzed. These deadly pens are found everywhere in the western forests. Two bears ranging along the south shore of English Lake, in Ashland County, Wisconsin, discovered some kegs of whiskey which contraband dealers had concealed there. With blows from their heavy paws they broke in the heads of the kegs and licked up the contents. They were soon in a very maudlin state, rolling about on the ground, embracing each other in an affectionate manner and vainly trying to go up the trees. Before the debauch was ended they were easily captured by a party of half-breeds. There are Indians who acknowledge the bear to be a relation, and profess a dislike to kill them. When they do they apologize, and say they do it because they are “buckoda,” or because it is necessary.

Detail of the Porcupine Mountains between the Montreal River and Ontonagon River from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

At Ontonagon, a very sorry looking young Indian came out of a lodge on the west side of the river and expressed a desire to take passage in our boat. There had been a great drunk in that lodge the day before. The squaws were making soup of the heads of white fish thrown away by the white fishermen. Some of the men were up, others oblivious to everything. Our passenger did not become thoroughly sober until towards evening. We passed the Lone Rock and encamped abreast of the Porcupine Mountains. Here he recovered his appetite. The next day, near the Montreal River, a squaw was seen launching her canoe and steering for us. She accosted the young fellow, demanding a keg of whiskey. He said nothing. She had given him furs enough to purchase a couple of gallons and he had made the purchase, but between himself and his friends it had completely disappeared. The old hag was also fond of whiskey. The fraud and disappointment put her into a rage that was absolutely fiendish. Her haggard face, long, coarse, greasy, black hair, voluble tongue and shrill voice perfected that character.

Turning into the mouth of the river we found a party from Lake Flambeau fishing in the pool at the foot of the Great Fall. Their success had not been good, and of course they were hungry. One of our men spilled some flour on the sand, of which he could save but little. The Flambeaus were delighted, and, gathering up sand and flour together, put the mixture in their kettle. The sand settled at the bottom, and the flour formed an excellent porridge for hungry aboriginees.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Mushinnewa and Waubannika, Chippewas, lived at Bad River, near Odana. Mushinnewa had a very bad reputation among his tribe. He was not only quarrelsome when drunk, but was not peaceable when sober. He broke Waubannika’s canoe into fragments, which was resented by the wife of the latter on the spot. She made use of the awl with which she was sewing the bark on another canoe, as a weapon, and stabbed old Mushinnewa in several places so severely that it was thought he would die. He threatened to kill her, and she fled with her husband to Lake Flambeau. But Mushinnewa did not die. He had a son as little liked by the Odana band as himself. In a drunken affray at Ontonagon another Indian killed him. The murderer then took the body in his canoe, brought it to Bad River and delivered it to old Mushinnewa. According to custom the Indian handed the enraged father the knife with which his son was killed, and baring his breast told him to strike. The villagers were happy to be rid of the young villain, and took the knife from the hand of his legal avenger. A barrel of flour covered the body, and before night Mushinnewa adopted the Indian as his son.