“A real bona fide, unmitigated Irishman”

December 7, 2014

By Leo

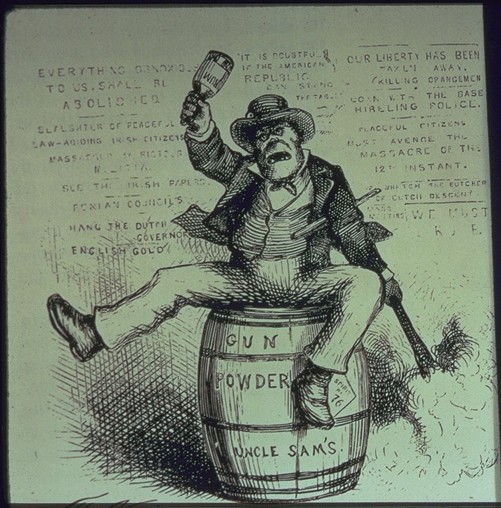

“The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things”, by Thomas Nast Published 2 September 1871 in Harper’s Weekly. Nast, who battled Tammany Hall and designed the modern image of Santa Claus, is one of the most famous American political cartoonists. However, he frequently depicted Irish-Americans as drunken, monkey-like monsters (Wikimedia Images).

It has been a while since I’ve posted anything new. My personal life has made it impossible to meet my former quota of three new posts a month. Now, it seems like I’ll be lucky to get one every three months. I haven’t forgotten about this site, however, and there is certainly no shortage of new topics. Unfortunately, most of them require more effort than I am able to give right now. Today, however, I have a short one.

Regular readers will know that the 1855 La Pointe annuity payment to the Lake Superior Chippewa bands is a frequent subject on Chequamegon History. To fully understand the context of this post, I recommend reading some of the earlier posts on that topic. The 1855 payment produced dozens of interesting stories and anecdotes: some funny, some tragic, some heroic, some bizarre, and many complicated. We’ve covered everything from Chief Buffalo’s death, to Hanging Cloud the female warrior, to Chief Blackbird’s great speech, to the random arrival of several politicians, celebrities, and dignitaries on Madeline Island.

Racism is an unavoidable subject in nearly all of these stories. The decisive implementation of American power on the Chequamegon Region in the 1850s cannot be understood without harshly examining the new racial order that it brought.

The earlier racial order (Native, Mix-blood, European) allowed Michel Cadotte Jr., being only of one-eighth European ancestry to be French while Antoine Gendron, of full French ancestry, was seen as fully Ojibwe. The new American order, however, increasingly defined ones race according to the shade of his or her skin.

But there are never any easy narratives in the history of this area, and much can be missed if the story of American domination is only understood as strictly an Indian/White conflict. There are always misfits, and this area was full of them.

I recently found an example from the November 7, 1855 edition of the Western Reserve Chronicle in Warren, Ohio shows just how the suffocating paternalism directed toward the Ojibwe at the 1855 payment hit others as well:

A GENUINE IRISHMAN

A correspondent of the Home Journal relates the following characteristic incident of Irish tactic. He says:

Does the wide world contain another paradox that will compare with a real bona fide, unmitigated Irishman? Imagination and sensuality, poetry and cupidity, generosity and avarice, heroism and cowardice–and so on, to the end of the list; all colors, shades and degrees of character congregated together, and each in most intimate association with its intensest antithesis–a very Joseph’s coat, and yet, most marvelous of marvels! a perfect harmony pervading the whole.

Among the reminiscences of a month’s sojourn at La Pointe, Lake Superior, during the annual Indian payment of the last summer, I find the following truly ‘representative’ anecdote:

One day while Commissioner Monypenny was sitting in council with the chiefs, intelligence was brought to Mr. Gilbert (the Indian agent) that two or three Indians were drunk and fighting, at a certain wigwam. With his usual promptitude, Mr. Gilbert summoned one of his interpreters, and proceeded directly to the lodge, where he seized the parties and locked them in the little wooden jail of the village, having first ascertained from them where they obtained their liquor. He then went immediately to the house they had designated, which was a private dwelling, occupied by an Irishman and his wife, and demanded if they kept liquor to sell to the Indians.

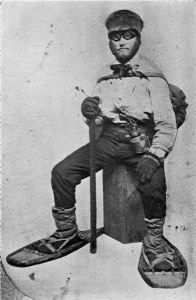

Henry C. Gilbert was the Indian Agent during the Treaty of 1854 and oversaw the 1855 annuity payment along with Commissioner of Indian Affairs George Manypenny (Branch County Photographs).

Both the man and woman, with rational vehemence and volubility–and both at once, of course, utterly denied having ‘a dhrop in the house, more nor a little jug full, which we just kape by us, like, for saysonin’ the vittals, and sickness.’ But, unfortunately for the veracity of the parties, on searching the premises, the interpreter discovered, in a little back wood-shed, two barrels of whiskey, besides the ‘little jug’ which proved to be a two gallon one, and full.

Mr. Gilbert ordered some of his men to roll the barrels out on the green, where in the presence of the whole council, they knocked in head, and the jug broken. But the flow of whisky was as nothing compared with the Irish wife’s temper, meanwhile. I had never conceived it possible for a tongue to possess such leverage; it seemed literally to be ‘hung in the middle and to work both ways.’ However, mother Earth drank the whisky, and the abuse melted into ‘the circumambient air’–though one would not have suspected their volubility, they seemed to be such concrete masses of venom.

In the evening of the same day, as Col. Monypenny was walking out with a friend, he encountered and was accosted by, the Irish whisky vender.

‘The first star of the avenin’ to yees, Misther Commissioner! An’ sure it was a bad thrick ye were putting on a poor mon, this mornin’. Och, murther! to think how ye dissipayted the illegant whisky; but ye’ll not be doin’ less nor payin’ me the first cost of it, will ye?’

‘On the contrary,’ said the commissioner, ‘we are thinking of having you up in the morning, and fining you; and if we catch you selling another drop to the Indians, we shall forcibly remove you from the island.’

Quick as–but I despair of a simile, for surely there is no operation of nature or art that will furnish a parallel to the agility of an Irishman’s wit–his whole tone and manner changed, and dropping his voice to the pitch confidential, he said:

‘Wll, Misther Commissioner, an’ its truth I’m tellin’ ye–its mighty glad I was, intirely, to see the dirty barrels beheaded; sure I’d a done it meself, for the moral of the thing, ef it hadn’t been for the ould woman. Good avenin’ to ye, Misther Commissioner.’

It is hardly necessary to add that no further application was made for the ‘first cost of it.’

Very truly yours.

~ Western Reserve chronicle. (Warren, Ohio) November 07, 1855

(Library of Congress Chronicling America Historic Newspaper Collection)

The sale of alcohol was illegal at La Pointe at that time. However, the law was generally impossible to enforce and liquor flowed freely into and out of the island.

Admittedly I chuckled at the depiction of the Irish wit and the temper of the “Irish wife,” but as a descendant of immigrants who fled the Great Famine in the 1840s, it’s hard to read the condescending stereotypes my ancestors would have been subjected to.

That said, it’s important to note that the two or three Ojibwe people in this story were imprisoned without charges or trial for drinking, while the couple selling the illegal liquor only lost his stock and wasn’t fined. This is something those of us of European descent need to be careful of when trying to draw equivalencies.

So then who was the bona fide, unmitigated Irishman?

Hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants came to America during the 1840s and ’50s. Inevitably, some of them ended up in this area. However, by 1855 it was only a handful.

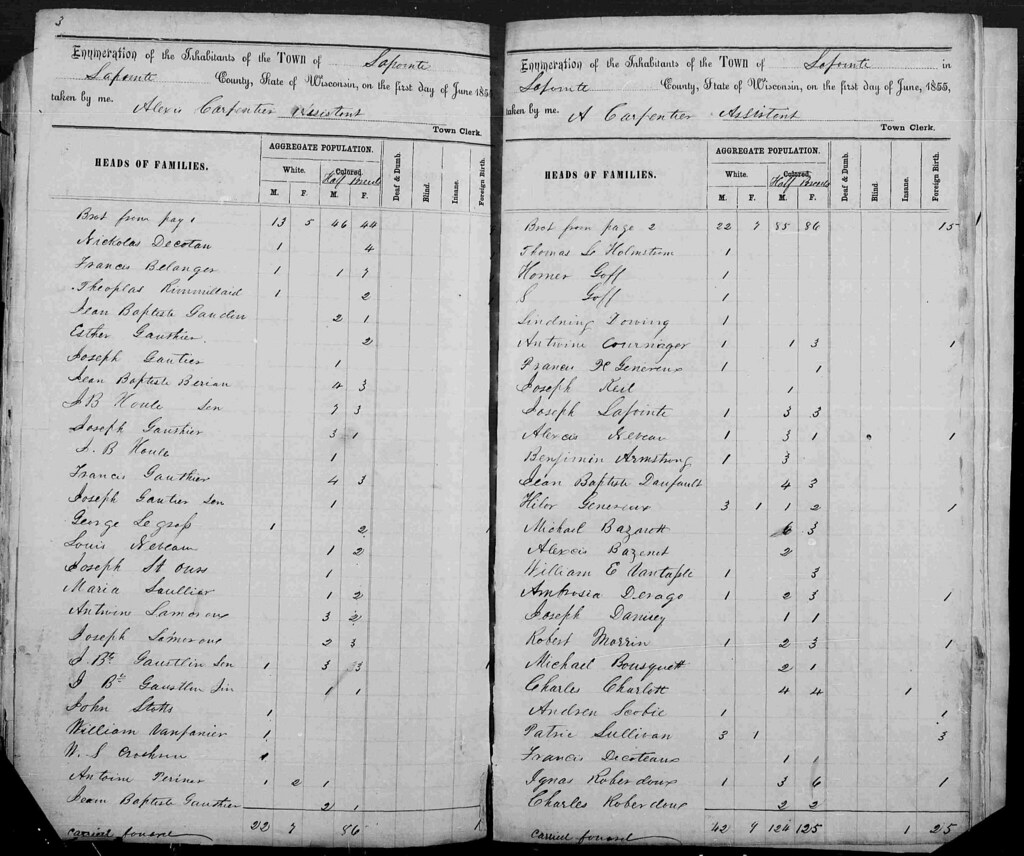

Just a few weeks prior to the payment, Alexis Carpentier, a former voyageur from a mixed French-Ojibwe family was charged with taking the Wisconsin State Census for La Pointe County. He found 37 residents of foreign birth. Most of these were French or mix-blooded men, born in Canada, who married into local Ojibwe and mix-blood families.

In only one household, more than one person is listed as being foreign-born. This was the home of Patric Sullivan. State censuses only listed the name of the head of household and do not list country of origin. However, in the 1860 Federal census, we find Patrick and Johanna Sullivan living with their three sons in La Pointe township. Both were born in Ireland.

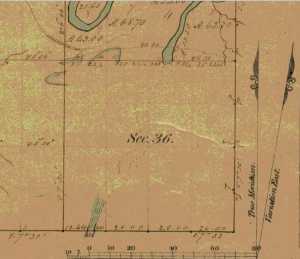

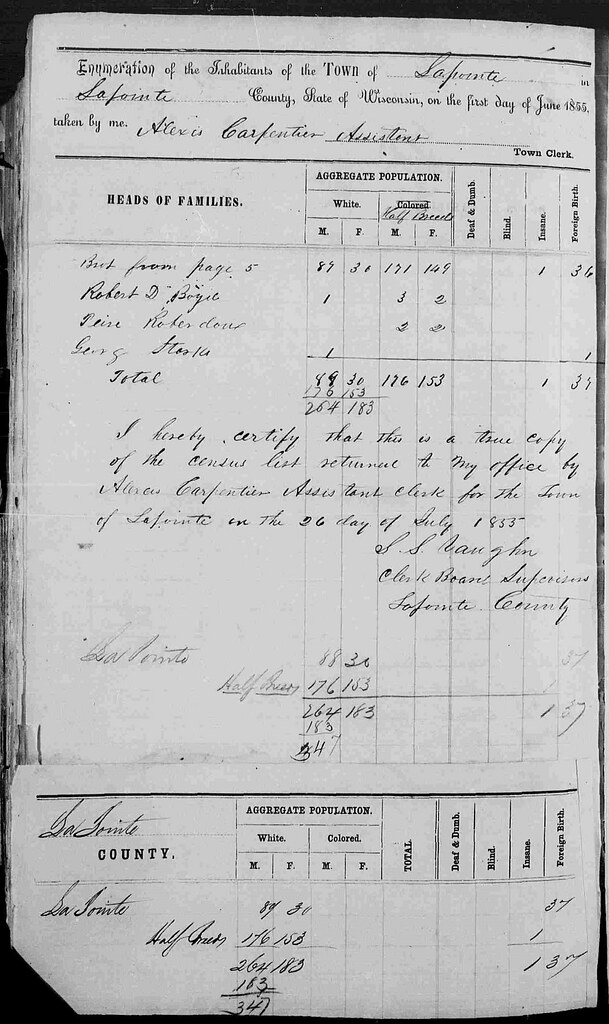

Page 1 of 1855 Wisconsin State Census for La Pointe County (familysearch.org)

Pages 2 and 3. Patric Sullivan is fourth from the bottom on the right side. enlarge

Patrick Sullivan did not sign the LaPoint Agreement to Stop Whiskey Trade of September 10, 1855. In fact, I haven’t been able to find much information at all about Patrick and Johanna Sullivan in later years. It does appear the family stayed in the area and their children were still living in Ashland at the dawn of the 20th century.

Finally, since this post deals with the 1855 census and issues of race and identity, it’s worth noting another interesting fact. The state census had only two categories for race: “White” and “Colored.” As non-citizens, full-blooded Ojibwe people would not have been counted among the 447 names on the census. However, it seems that Carpentier and his boss, La Pointe town clerk Samuel S. Vaughn, were not sure how to categorize by race.

Carpentier crossed out the designation “Colored” and replaced it with “Half-Breed.” By their count, 329 “Half-Breeds” and 118 Whites (many of them in mixed families) lived in La Pointe County in 1855. Mix-bloods were considered Ojibwe tribal members under the Treaty of 1847. However, they traditionally had their own identity and were thought eligible for U.S. citizenship.

One wonders what conversations were had as the census was completed, but in the final compilation, all 447 names (including several core Red Cliff and Bad River families) were submitted to the state as “White” rather than “Colored.” Despite America’s best efforts to create a racial duality, which would only intensify following the Civil War, this region would continue to defy such categorization for the remainder of the 19th century.

Sources:

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Life among the Lake Superior Ojibway. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1985. Print.

Miller, Kerby A. Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Print.

NOTES: Research originally featured on Chequamegon History is featured in the new Changing Currents exhibit opening today at the Chippewa Valley Museum in Eau Claire. I had a chance to preview the exhibit on Friday, and John Vanek and crew have created an incredibly well-done display of Ojibwe treaty and removal politics of the mid 1800s. See their website for more information. The research found in this exhibit, which extends into several topics, is very deep and does not shy away from uncomfortable topics. I highly recommend it.

There may be some exciting guest research featured on Chequamegon History in the coming months dealing with the aftermath of the 1854 Treaty and fraudulent land claims in the Penokee Iron Range. Stay tuned.