In the Fall of 1850, the Lake Superior Ojibwe (Chippewa) bands were called to receive their annual payments at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi River. The money was compensation for the cession of most of northern Wisconsin, Upper Michigan, and parts of Minnesota in the treaties of 1837 and 1842. Before that, payments had always taken place in summer at La Pointe. That year they were switched to Sandy Lake as part of a government effort to remove the entire nation from Wisconsin and Michigan in blatant disregard of promises made to the Ojibwe just a few years earlier.

There isn’t enough space in this post to detail the entire Sandy Lake Tragedy (I’ll cover more at a later date), but the payments were not made, and 130-150 Ojibwe people, mostly men, died that fall and winter at Sandy Lake. Over 250 more died that December and January, trying to return to their villages without food or money.

George Warren (b.1823) was the son of Truman Warren and Charlotte Cadotte and the cousin of William Warren. (photo source unclear, found on Canku Ota Newsletter)

If you are a regular reader of Chequamegon History, you will recognize the name of William Warren as the writer of History of the Ojibway People. William’s father, Lyman, was an American fur trader at La Pointe. His mother, Mary Cadotte was a member of the influential Ojibwe-French Cadotte family of Madeline Island. William, his siblings, and cousins were prominent in this era as interpreters and guides. They were people who could navigate between the Ojibwe and mix-blood cultures that had been in this area for centuries, and the ever-encroaching Anglo-American culture.

The Warrens have a mixed legacy when it comes to the Sandy Lake Tragedy. They initially supported the removal efforts, and profited from them as government employees, even though removal was completely against the wishes of their Ojibwe relatives. However, one could argue this support for the government came from a misguided sense of humanitarianism. I strongly recommend William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader by Theresa Schenck if you are interested in Warren family and their motivations. The Wisconsin Historical Society has also digitized several Warren family letters, and that’s what prompted this post. I decided to transcribe and analyze two of these letters–one from before the tragedy and one from after it.

The first letter is from Leonard Wheeler, a missionary at Bad River, to William Warren. Initially, I chose to transcribe this one because I wanted to get familiar with Wheeler’s handwriting. The Historical Society has his papers in Ashland, and I’m planning to do some work with them this summer. This letter has historical value beyond handwriting, however. It shows the uncertainty that was in the air prior to the removal. Wheeler doesn’t know whether he will have to move his mission to Minnesota or not, even though it is only a month before the payments are scheduled.

Sept 6, 1850

Dear Friend,

I have time to write you but a few lines, which I do chiefly to fulfill my promise to Hole in the Day’s son. Will you please tell him I and my family are expecting to go Below and visit our friends this winter and return again in the spring. We heard at Sandy Lake, on our way home, that this chief told [Rev.?] Spates that he was expecting a teacher from St. Peters’ if so, the Band will not need another missionary. I was some what surprised that the man could express a desire to have me come and live among his people, and then afterwards tell Rev Spates he was expecting a teacher this fall from St. Peters’. I thought perhaps there was some where a little misunderstanding. Mr Hall and myself are entirely undecided what we shall do next Spring. We shall wait a little and see what are to be the movements of gov. Mary we shall leave with Mr Hall, to go to school during the winter. We think she will have a better opportunity for improvement there, than any where else in the country. We reached our home in safety, and found our families all well. My wife wishes a kind remembrance and joins me in kind regards to your wife, Charlotte and all the members of your family. If Truman is now with you please remember us to him also. Tomorrow we are expecting to go to La Pointe and take the Steam Boat for the Sault monday. I can scarcely realize that nine years have passed away since in company with yourself and Pa[?] Edward[?] we came into the country.

Mary is now well and will probably write you by the bearer of this.

Very truly yours

L. H. Wheeler

By the 1850s, Young Hole in the Day was positioning himself to the government as “head chief of all the Chippewas,” but to the people of this area, he was still Gwiiwiizens (Boy), his famous father’s son. (Minnesota Historical Society)

By the 1850s, Young Hole in the Day was positioning himself to the government as “head chief of all the Chippewas,” but to the people of this area, he was still Gwiiwiizens (Boy), his famous father’s son. (Minnesota Historical Society)Samuel Spates was a missionary at Sandy Lake. Sherman Hall started as a missionary at La Pointe and later moved to Crow Wing.

Mary, Charlotte, and Truman Warren are William’s siblings.

The Wheeler letter is interesting for what it reveals about the position of Protestant missionaries in the 1850s Chequamegon region. From the 1820s onward, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent missionaries, mostly Congregationalists and Presbyterians from New England, to the Lake Superior Country. Their names, Wheeler, Hall, Ely, Boutwell, Ayer, etc. are very familiar to historians, because they produced hundreds of pages of letters and diaries that reveal a great deal about this time period.

Leonard H. Wheeler (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Ojibwe people reacted to these missionaries in different ways. A few were openly hostile, while others were friendly and visited prayer, song, and school meetings. Many more just ignored them or regarded them as a simple nuisance. In forty-plus years, the amount of Ojibwe people converted to Protestantism could be counted on one hand, so in that sense the missions were a spectacular failure. However, they did play a role in colonization as a vanguard for Anglo-American culture in the region. Unlike the traders, who generally married into Ojibwe communities and adapted to local ways to some degree, the missionaries made a point of trying to recreate “civilization in the wilderness.” They brought their wives, their books, and their art with them. Because they were not working for the government or the Fur Company, and because they were highly respected in white-American society, there were times when certain missionaries were able to help the Ojibwe advance their politics. The aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy was such a time for Wheeler.

This letter comes before the tragedy, however, and there are two things I want to point out. First, Wheeler and Sherman Hall don’t know the tragedy is coming. They were aware of the removal, and tentatively supported it on the grounds that it might speed up the assimilation and conversion of the Ojibwe, but they are clearly out of the loop on the government’s plans.

Second, it seems to me that Hole in the Day is giving the missionaries the runaround on purpose. While Wheeler and Spates were not powerful themselves, being hostile to them would not help the Ojibwe argument against the removal. However, most Ojibwe did not really want what the missionaries had to offer. Rather than reject them outright and cause a rift, the chief is confusing them. I say this because this would not be the only instance in the records of Ojibwe people giving ambiguous messages to avoid having their children taken.

Anyway, that’s my guess on what’s going on with the school comment, but you can’t be sure from one letter. Young Hole in the Day was a political genius, and I strongly recommend Anton Treuer’s The Assassination of Hole in the Day if you aren’t familiar with him.

I read this as “passed away since in company with yourself and Pa[?] Edward we came into the country.” Who was Wheeler’s companion when a young William guided him to La Pointe? I intend to find out and fix this quote. (from original in the digital collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society)

In 1851, Warren was in failing health and desperately trying to earn money for his family. He accepted the position of government interpreter and conductor of the removal of the Chippewa River bands. He feels removing is still the best course of action for the Ojibwe, but he has serious doubts about the government’s competence. He hears the desires of the chiefs to meet with the president, and sees the need for a full rice harvest before making the journey to La Pointe. Warren decides to stall at Lac Courte Oreilles until all the Ojibwe bands can unite and act as one, and does not proceed to Lake Superior as ordered by Watrous. The agent is getting very nervous.

Clement and Paul (pictured) Hudon Beaulieu, and Edward Conner, were mix-blooded traders who like the Warrens were capable of navigating Anglo-American culture while maintaining close kin relationships in several Ojibwe communities. Clement Beaulieu and William Warren had been fierce rivals ever since Beaulieu’s faction drove Lyman Warren out of the American Fur Company. (Photo original unknown: uploaded to findadagrave.com by Joan Edmonson)

Clement and Paul (pictured) Hudon Beaulieu, and Edward Conner, were mix-blooded traders who like the Warrens were capable of navigating Anglo-American culture while maintaining close kin relationships in several Ojibwe communities. Clement Beaulieu and William Warren had been fierce rivals ever since Beaulieu’s faction drove Lyman Warren out of the American Fur Company. (Photo original unknown: uploaded to findadagrave.com by Joan Edmonson)For more on Cob-wa-wis (Oshkaabewis) and his Wisconsin River band, see this post.

“Perish” is what I see, but I don’t know who that might be. Is there a “Parrish”, or possibly a “Bineshii” who could have carried Watrous’ letter? I’m on the lookout. (from original in the digital collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society)

Aug 9th 1851

Friend Warren

I am now very anxiously waiting the arrival of yourself and the Indians that are embraced in your division to come out to this place.

Mr. C. H. Beaulieu has arrived from the Lake Du Flambeau with nearly all that quarter and by an express sent on in advance I am informed that P. H. Beaulieu and Edward Conner will be here with Cob-wa-wis and they say the entire Wisconsin band, there had some 32 of the Pillican Lake band come out and some now are in Conner’s Party.

I want you should be here without fail in 10 days from this as I cannot remain longer, I shall leave at the expiration of this time for Crow Wing to make the payment to the St. Croix Bands who have all removed as I learn from letters just received from the St. Croix. I want your assistance very much in making the Crow Wing payment and immediately after the completion of this, (which will not take over two days[)] shall proceed to Sandy Lake to make the payment to the Mississippi and Lake Bands.

The goods are all at Sandy Lake and I shall make the entire payment without delay, and as much dispatch as can be made it; will be quite lots enough for the poor Indians. Perish[?] is the bearer of this and he can tell you all my plans better then I can write them. give My respects to your cousin George and beli[e]ve me

Your friend

J. S. Watrous

W. W. Warren Esq.}

P. S. Inform the Indians that if they are not here by the time they will be struck from the roll. I am daily expecting a company of Infantry to be stationed at this place.

JSW

Sources:

Schenck, Theresa M., William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Treuer, Anton. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul, MN: Borealis, 2010. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

…a donation of twenty-four sections of land covering the graves of our fathers, our sugar orchards, and our rice lakes and rivers…

March 29, 2013

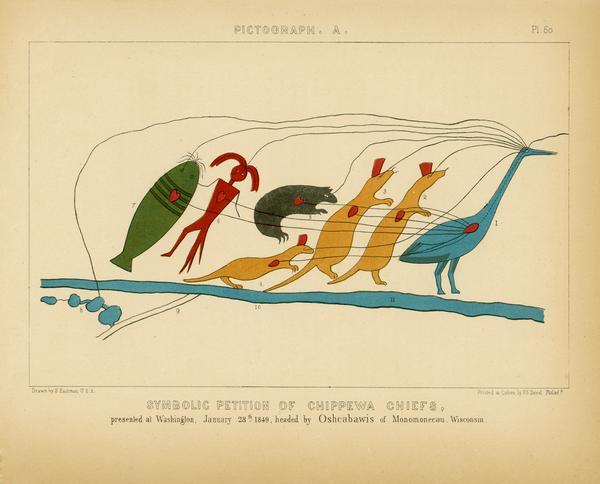

Symbolic Petition of Chippewa Chiefs: Original birch bark petition of Oshkaabewis copied by Seth Eastman and printed in “Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States” by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (1851). Digitized by University of Wisconsin Libraries Wisconsin Electronic Reader project (1998).

For the first post on Chequamegon History, I thought I’d share my research into an image that has been circulating around the area for several years now. The image shows seven Ojibwe chiefs by their doodemag (clan symbols), connected by heart and mind to Lake Superior and to some smaller lakes. The clans shown are the Crane, Marten, Bear, Merman, and Bullhead.

All the interpretations I’ve heard agree that this image is a copy of a birch bark pictograph, and that it represents a unity among the several chiefs and their clans against Government efforts to remove the Lake Superior bands to Minnesota.

While there is this agreement on the why question of this petition’s creation, the who and when have been a source of confusion. Much of this confusion stems from efforts to connect this image to the famous La Pointe chief, Buffalo (Bizhiki/Gichi-weshkii).

In 2007, the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) released the short documentary Mikwendaagoziwag: They Are Remembered. While otherwise a very good overview of the Lake Superior Ojibwe in this era, it incorrectly uses this image to describe Buffalo going to Washington D.C. in 1849. Buffalo is famous for a trip to Washington in 1852, but he was not part of the 1849 group.

At the time the GLIFWC film was released, the Wisconsin Historical Society website referred to this pictograph as, “Chief Buffaloʼs Petition to the President,” and identified the crane as Buffalo. Citing oral history from Lac Courte Oreilles, the Society dated the petition after the botched 1850-51 removal to Sandy Lake, Minnesota that resulted in hundreds of Ojibwe deaths from disease and starvation due to negligence, greed, and institutional racism on the part of government officials. The Historical Society has since revised its description to re-date the pictograph at 1848-49, but it still incorrectly lists Buffalo, a member of the Loon Clan, as being depicted by the crane. The Sandy Lake Tragedy, has deservedly gained coverage by historians in recent years, but the pictographic petition came earlier and was not part of it.

If the Historical Society had contacted Chief Buffaloʼs descendants in Red Cliff, they would have known that Buffalo was from the Loon Clan. The relationship between the Loons and the Cranes, as far as which clan can claim the hereditary chieftainship of the La Pointe Band, is very interesting and covered extensively in Warrenʼs History of the Ojibwe People. It would make a good subject for a future post.

After looking into the history of this image, I can confidently say that Buffalo is not one of the chiefs represented. It was created before Sandy Lake and Buffalo’s journey, but it is related to those events. Here is the story:

In late 1848, a group of Ojibwe chiefs went to Washington. They wanted to meet directly with President James K. Polk to ask for a permanent reservations in Wisconsin and Michigan. At that time the Ojibwe did not hold title to any part of the newly-created state of Wisconsin or Upper Michigan, having ceded these lands in the treaties in 1837 and 1842. In signing the treaties, they had received guarantees that they could stay in their traditional villages and hunt, fish, and gather throughout the ceded territory. However, by 1848, rumors were flying of removal of all Ojibwe to unceded lands on the Mississippi River in Minnesota Territory. These chiefs were trying to stop that from happening.

John Baptist Martell, a mix-blood, acted as their guide and interpreter. The government officials and Indian agents in the west were the ones actively promoting removal, so they did not grant permission (or travel money) for the trip. The chiefs had to pay their way as they went by putting themselves on display and dancing as they went from town to town.

Martell was accused by government officials of acting out of self interest, but the written petition presented to congress asked for, “a donation of twenty-four sections of land covering the graves of our fathers, our sugar orchards, and our rice lakes and rivers, at seven different places now occupied by us at villages…” The chiefs claimed to be acting on behalf of the chiefs of all the Lake Superior bands, and there is reason to believe them given that their request is precisely what Chief Buffalo and other leaders continued to ask for up until the Treaty of 1854.

This written petition accompanied the pictographic petitions. It clearly states the goal of the the chiefs was to secure permanent reservations around the traditional villages east of the Mississippi.

The visiting Ojibwes made a big impression on the nationʼs capital and positive accounts of the chiefs, their families, and their interpreter appeared in the magazines of the day. Congress granted them $6000 for their expenses, which according to their critics was a scheme by Martell. However, it is likely they were vilified by government officials for working outside the colonial structure and for trying to stop the removal rather than for any ill-intentions of the part of their interpreter. A full scholarly study of the 1848-49 trip remains to be done, however.

Amid articles on the end of the slave trade, the California Gold Rush, and the benefits of the “passing away of the Celt” during the Great Irish Famine, two articles appeared in Littell’s Living Age magazine about the 1849 delegation. The first is tragic, and the second is comical.

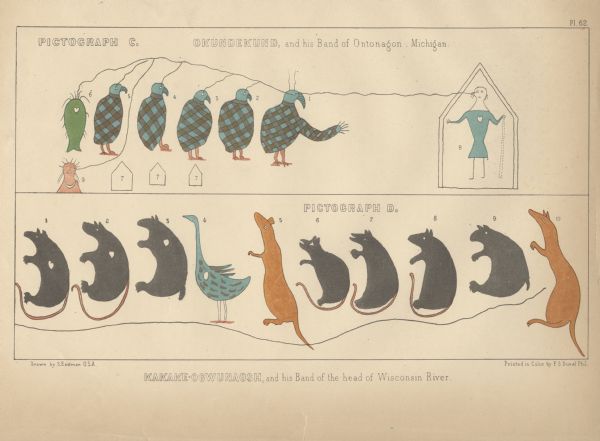

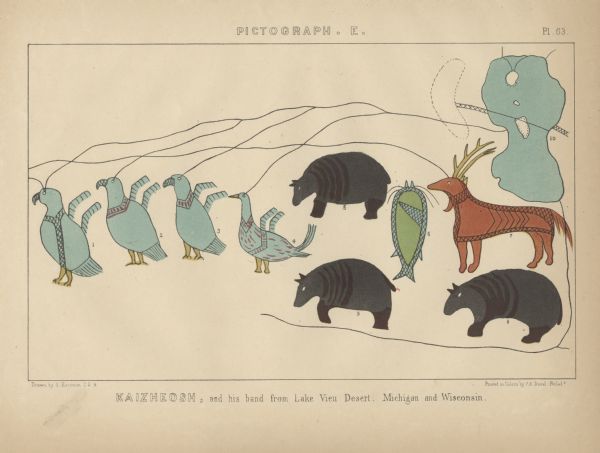

Along with written letters and petitions supporting the Ojibwe cause, the chiefs carried not only the one, but several birchbark pictographs. The pictographs show the clan animals of several chiefs and leading men from several small villages from the mouth of the Ontonagon River to Lac Vieux Desert in Upper Michigan and smaller satellite communities in Wisconsin. After seeing these petitions, the artist Seth Eastman copied them on paper and gave them to Henry Schoolcraft who printed and explained them alongside his criticism of the trip. They appear in his 1851 Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States.

Kenisteno, and his Band of Trout Lake, Wisconsin

Okundekund, and his Band of Ontonagon, Michigan (Upper) Kakake-ogwunaosh, and his Band of the head of Wisconsin River (Lower)

According to Schoolcraft, the crane in the most famous pictograph is Oshkaabewis, a Crane-clan chief from Lac Vieux Desert, and the leader of the 1848-49 expedition. In the Treaty of 1854, he is listed as a first chief from Lac du Flambeau in nearby Wisconsin. It makes sense that someone named Oshkaabewis would lead a delegation since the word oshkaabewis is used to describe someone who carries messages and pipes for a civil chief.

Kaizheosh [Gezhiiyaash], and his band from Lake Vieu Desert, Michigan and Wisconsin (University of Nebraska Libraries)

Long Story Short…

This is not Chief Buffalo or anyone from the La Pointe Band, and it was created before the Sandy Lake Tragedy. However it is totally appropriate to use the image in connection with those topics because it was all part of the efforts of the Lake Superior Ojibwe to resist removal in the late 1840s and early 1850s. However, when you do, please remember to credit the Lac Vieux Desert/Ontonagon chiefs who created these remarkable documents.

The Old Mission Church, La Pointe, Madeline Island. (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: 24827)

The Old Mission Church, La Pointe, Madeline Island. (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: 24827) Harriet Wheeler, pictured about forty years after receiving this letter. (Wisconsin Historical Society: Image ID 36771)

Harriet Wheeler, pictured about forty years after receiving this letter. (Wisconsin Historical Society: Image ID 36771) Many Ojibwe leaders, including Hole in the Day, blamed the rotten pork and moldy flour distributed at Sandy Lake for the disease that broke out. The speech in St. Paul is covered on pages 101-109 of Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader, my favorite book about this time period. (Photo from Whitney’s Gallery of St. Paul: Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID 27525)

Many Ojibwe leaders, including Hole in the Day, blamed the rotten pork and moldy flour distributed at Sandy Lake for the disease that broke out. The speech in St. Paul is covered on pages 101-109 of Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and Times of an Ojibwe Leader, my favorite book about this time period. (Photo from Whitney’s Gallery of St. Paul: Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID 27525) Mary Warren (1835-1925), was a teenager at the time of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. She is pictured here over seventy years later. Mary, the sister of William Warren, had been living with the Wheelers but stayed with Hall during their trip east. (Photo found on

Mary Warren (1835-1925), was a teenager at the time of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. She is pictured here over seventy years later. Mary, the sister of William Warren, had been living with the Wheelers but stayed with Hall during their trip east. (Photo found on