Diplomacy in the Time of Cholera: why there was no Ojibwe delegation to President Taylor in the winter of 1849-50

December 15, 2024

By Leo

At Chequamegon History, we deal mostly in the micro. By limiting our scope to a particular time and place, we are all about the narrow picture. Don’t come here for big universal ideas. The more specific and obscure a story, the more likely it is to appear on this website.

Madeline Island and the Chequamegon region are perfect for the specific and obscure. In the 1840s, most Americans would have thought of La Pointe as remote frontier wilderness, beyond the reach of worldwide events. Most of us still look at our history this way.

We are wrong. No man is an island, and Madeline Island–though literally an island–was no island.

This week, I was reminded of this fact while doing research for a project that has nothing to do with Chequamegon History. While scrolling through the death records of the Greek-Catholic church of my ancestral village in Poland, I noticed something strange. The causes of deaths are usually a mishmash of medieval sounding ailments, all written in Latin, or if the priest isn’t feeling creative or curious, the death is just listed as ordinaria.

In the summer of 1849, however, there was a noticeable uptick in death rate. It seemed my 19th-century cousins, from age 7 to 70, were all dying of the same thing:

Cause of death in right column. Akta stanu cywilnego Parafii Greckokatolickiej w Olchowcach (1840-1879). Księga zgonów dla miejscowości Olchowce. https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/en/jednostka/-/jednostka/22431255

Cholera is a word people my age first learned on our Apple IIs back in elementary school:

At Herbster School in 1990, we pronounced it “Cho-lee-ra.” It was weird the first time someone said “Caller-uh.” You can play online at https://www.visitoregon.com/the-oregon-trail-game-online/

It is no coincidence. If you note the date of leaving Matt’s General Store in Independence Missouri, Oregon Trail takes place in 1848.

Diseases thrive in times of war, upheaval, famine, and migration, and 1848 and 1849 certainly had plenty of all of those. A third year of potato blight and oppressive British policies plunged the Irish poor deeper into squalor and starvation. The millions who were able to, left Ireland. Meanwhile, the British conquest of the Punjab and the “Springtime of Nations” democratic revolutions across central Europe meant army and refugee camps (notorious vectors of disease) popped up across the Eurasian continent.

North America had seen war as well. The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (1848) ended the Mexican-American War and delivered half of Mexico over to Manifest Destiny. The discovery of gold in California, part of this cession, brought thousands of Chinese workers to the West Coast, while millions of Irish and Germans arrived on the East Coast. Some of those would also find their way west along the aforementioned Oregon Trail.

Closer to home, these German immigrants meant statehood for Wisconsin and the shifting of Wisconsin’s Indian administration west to Minnesota Territory. Eyeing profits, Minnesota and Mississippi River interests were increasingly calling for the removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe bands from Wisconsin and Michigan. This caused great alarm and uncertainty at La Pointe.

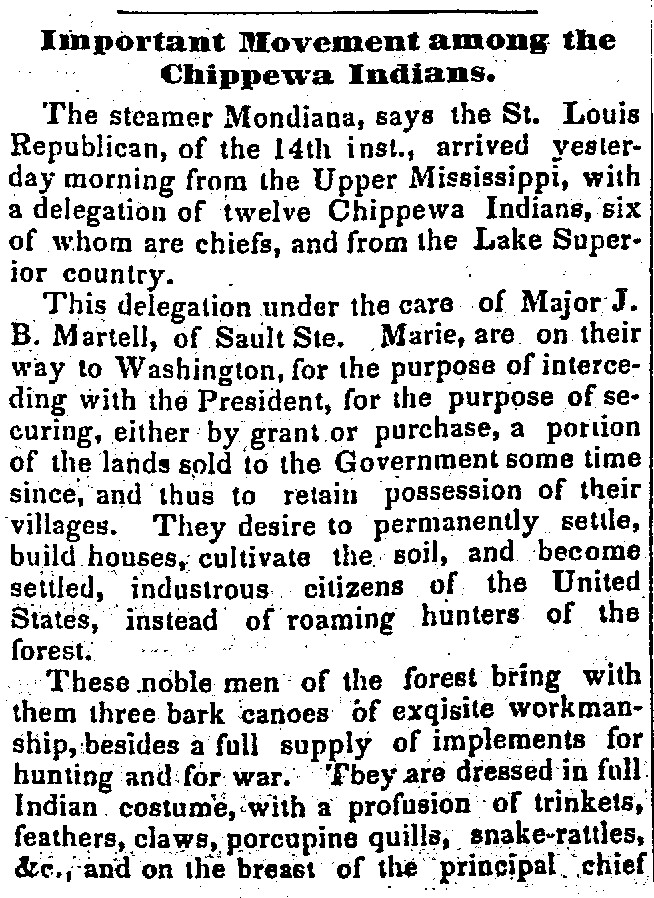

All of these seemingly disparate events of 1848 and 1849 are, in fact, related. One of the most obvious manifestations was that displaced people from all these places impacted by war, poverty, and displacement carried cholera. The disease arrived in the United States multiple times, but the worst outbreak came up Mississippi from New Orleans in the summer of 1849. It ravaged St. Louis, then the Great Lakes, and reached Sault Ste, Marie and Lake Superior by August.

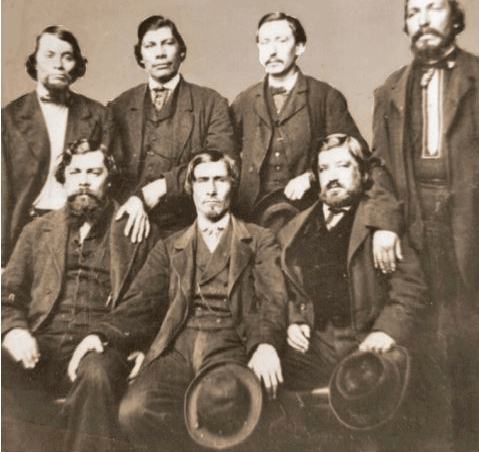

Longtime Chequamegon History readers will know my obsession with the Ojibwe delegation that left La Pointe in October 1848 and visited Washington D.C. in February 1849. It is a fascinating story of a group of chiefs who brought petitions (some pictographic) laying out their arguments against removal to President James K. Polk and Congress. The chiefs were well-received, but ultimately the substance of their petitions was not acted upon. They arrived after the 1848 elections. Polk and the members of Congress were lame ducks. General Zachary Taylor had been elected president, though he wasn’t inaugurated until the day after the delegation left Washington.

If you’ve read through our DOCUMENTS RELATED TO THE OJIBWE DELEGATION AND PETITIONS TO PRESIDENT POLK AND CONGRESS 1848-1849, you’ll know that both Polk and the Ojibwe delegation’s translator and alleged ringleader, the colorful Jean-Baptiste Martell of Sault Ste. Marie, died of cholera that summer.

So, in this post, we’re going to evaluate three new documents, just added to the collection, and look at how the cholera epidemic partially led to the disastrous removal of 1850, commonly known as the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

The first document is from just after the delegation’s arrival in Washington. It describes the meeting with Polk in great detail, lays out the Ojibwe grievances, and importantly, records Polk’s reaction. I have not been able to find the name of the correspondent, but this article is easily the best-reported of all the many, many newspaper accounts of the 1848-49 delegation–most of which use patronizing racist language and focus on the more trivial, “fish out of water” element of Lake Superior chiefs in the capital city.

New York Daily Tribune, 6 February 1849, Page 1

The Indians of the North-West–Their Wrongs–Chiefs in Washington

Correspondence of The Tribune

WASHINGTON, 3d Feb 1849.

Yesterday (Friday) the Chiefs representing the Chippewa Tribe of Indians located on the borders of Lake Superior and drawing their pay at La Pointe, representing 16 bands, which comprise about 9,000 Indians, after remaining here for the last ten days, were presented to the President.– The Secretary of War and Commissioner of Indian Affairs were also present. One of the Chiefs who appeared to be the eldest, first addressed the President, for a period of twenty minutes. The address was interpreted by John B. Martell, a half-breed, who was born and has always continued among them. He appears a shrewd, sensible man, and interprets with much fluency. This Chief was followed by two others in addresses occupying the same length of time. They all addressed the President as “Our Great Father,” and spoke with much energy, dignity and fluency, preserving throughout a respectful manner and evincing an earnest sincerity of purpose, that bespoke their mission to be one of no ordinary character. They represented their grievances under which their tribes were laboring: the trials and privations they had undergone to reach here, and the separation from their families, with much emotion and in truly touching and eloquent terms.

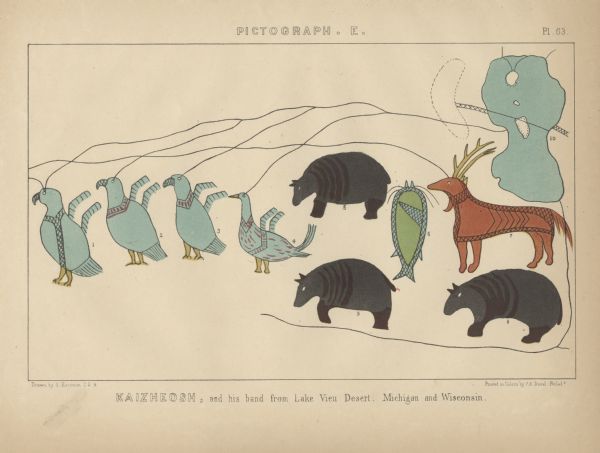

The oldest chief was Gezhiiyaash (his pictographic petition above) or “Swift Sailor” from Lac Vieux Desert. The two other chiefs were likely Oshkaabewis “Messenger” from Wisconsin River, and Naagaanab “Foremost Sitter” from Fond du Lac.

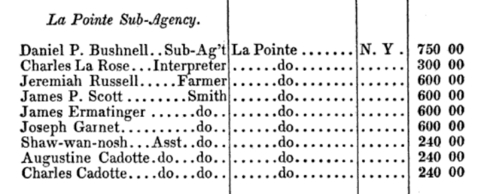

They represented that their annuities under their Treaty of La Pointe, made about the year 1843, were payable in the month of July in each year and not later, because by that time the planting season would be over; beside, it would be the best time and the least dangerous to pass the Great Lake and return to their homes in time to gather wild rice, on which they mainly depended during the hard winters. The first payment was made later than the time agreed upon. The agent, upon being notified, promised to comply with the terms of the Treaty, but every year since the payments have been made later, and that of last year did not take place until about the middle of October, in consequence of which they have been subjected to much suffering.– They assemble at the place for payment designated in the treaty. It is then the traders take advantage of them–being three hundred miles from home, without money, and without provisions; and when their money is received it must all be paid for their subsistence during the long delay they have been subjected to; and sickness frequently breaks out among them from being obliged to use salt provisions, which they are not accustomed to. By leaving their homes at any other time than in the month of July they neglect their harvesting–rice and potato crops, and if they neglect those they must starve to death; therefore it would be better for them to lose their annuities altogether. And without their blankets, procured at the Pointe, they are liable to freeze to death when passing the stormy lake; and the tradespeople influence the Agent to send for them a month before the payment is made, and when they arrive the Agent accepts orders from them for provisions which they are obliged to purchase at a great price–one dollar for 15 lbs of flour, and in proportion for other articles. They have assembled frequently in regard to these things, and can only conclude that their complaints have never reached their “Great Father,” and they have now come to see him in person, and take him by the hand.

In regard to the Half-Breeds at La Pointe, who draw pay with them, they say: That in the Treaty concluded between Governor Dodge and the Chippewas at St. Peters, provision was made for the half-breeds to draw their share all in one payment, and it was paid them accordingly, $258.50 each, which was a mere gift on the part of the tribe; a payment which they had no right to, but was given them as a present. Induced by some subsequent representations by the half-breeds, they were taken into their pay list, and the consequence has been that almost all the half breeds, as well as the French who are married to Indian women, are in the employ of, or dependent upon one of the principal trading houses, (Dr. Bourop’s) at La Pointe, with whom their goods and provisions are stored; and that they are thus enabled to select and appropriate to themselves the choice portion of all the goods designed for them–in many cases not leaving them a blanket to start with upon their journey of two or three hundred miles distant to their homes. After many other details, to which we will make reference in future articles, they urged that owing to the faithlessness of the half-breeds to them, and to the Government, that they be stricken from the pay list.

One half the goods furnished are of no use to them. The articles they most need are guns, kettles, blankets and a greater supply of provisions, &c.

They are under heavy expense, and no money to pay their board. They have undertaken this long journey for the benefit of their whole people, and at their earnest solicitations. They have been absent from their families nearly one year. It has cost them $1,400 to get here. Half of that sum has been raised from exhibitions. The other half has been borrowed from kind people on the route they have traveled. They wish to repay the money advanced them and to procure money to return home with. They want clothes and things to take to their families, and ask an appropriation of $6,000 on their annuity money.

They have before made a communication to the President, to be laid before the present Congress, for the acquisition of lands and the naturalization of their bands–propositions which they urged with great force.

All the Chiefs represented to the President that their interpreter, Mr. Martel, was living in very comfortable circumstances at home, and was induced to accompany them by the urgent solicitations of all their people who confided in his integrity and looked upon him as their friend.

The paternalistic ritual kinship (“Great Father”) language used here by James K. Polk, can be off-putting to the modern reader. However, it had a long tradition in Ojibwe “fur trade theater” rhetoric. Gezhiiyaash was no meek schoolboy, as evidenced by his words in this document (White House)

Their supplicating–though forcible, intelligent, and pathetic appeal, to be permitted to live upon the spot of their nativity, where the morning and noon of their days had been past, and the night time of their existence has reached them, was, too, and irresistible appeal to the justice, generosity and magnanimity of that boasted “civilization” that pleads mercy to the conquered, and was calculated to leave an impress upon every honest heart who claims to be a “freeman.”

The President, in answer to the several addresses, requested the interpreter to state to them that their Great Father was happy to have met with them; and as they had made allusion to written documents which they placed in his hands, as containing an expression of their views and wishes, he would carefully read them and communicate his answer to the Secretary of War and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, assuring them of kindly feelings on the part of the Government, and terminating with some expressions very like a schoolmaster’s enjoinder upon his scholars that if they behaved themselves they might expect good treatment in future.

The fact that they met Polk was not new information, but we hadn’t been previously aware of just how long the meeting went. It is important to note the president’s use of “kindly feelings” and “behaved themselves.” Those phrases would come up frequently in subsequent years.

One could argue that Polk was a lame duck, and would be dead of cholera within a few months, so his words didn’t mean much. One could argue the problem was that the Ojibwe didn’t understand that in the American political system–that the incoming Whig administration might not feel bound by the words and “kindly feelings” of the outgoing Democratic administration.

However, the next document shows that the chiefs did feel the need to cover their bases and stuck around Washington long enough meet the next president. To us, at least, this was new information:

National Era v. III. No. 14, pg. 56 April 5, 1849

For the National Era

THE CHIPPEWA CHIEFS AND GENERAL TAYLOR

On the third day after the arrival of General Taylor at Washington, the Indian chiefs requested me to seek an interview for them, as they were about to leave for their homes, on Lake Superior, and greatly desired to see the new President before their departure.

It was accordingly arranged by the General to see them the next morning at 9 o’clock, before the usual reception hour.

Fitted out in their very best, with many items of finery which their taste for the imposing had added to their wardrobe, the delegation and their interpreter accompanied me to the reception room, and were cordially taken by the hand by the plain but benevolent-looking old General. One of the chiefs arose, and addressed the President elect nearly as follows:

“Father! We are glad to see you, and we are pleased to see you so well after your long journey.

“Father! We are the representatives of about twenty thousand of your red children, and are just about leaving for our homes, far off on Lake Superior, and we are very much gratified, that, before our departure, we have the opportunity of shaking hands with you.

“Father! You have conquered your country’s enemies in war; may you subdue the enemies of your Administration while you are President of the United States and govern this great country, like the great father, Washington, before you, with wisdom and in peace.

“Father! This our visit through the country and to the cities of your white children, and the wonderful things that we have seen, impress us with awe, and cause us to think that the white man is the favored of the Great Spirit.

“Father! In the midst of the great blessings with which you and your white children are favored of the Great Spirit, we ask of you, while you are in power, not to forget your less fortunate red children. They are now few, and scattered, and poor. You can help them.

“Father! Although a successful warrior, we have heard of your humanity! And now that we see you face to face, we are satisfied that you have a heart to feel for your poor red children.

“Father Farewell”

The tall, manly-looking chief having finished and shaken hands, General Taylor asked him to be seated, and, rising himself, replied nearly as follows”

“My Red Children: I am very happy to have this interview with you. What you have said I have listened to with interest. It is the more appreciated by me, as I am no stranger to your people. I resided for a length of time on your borders, and have been witness to your privations, and am acquainted with many of your wants.

“Peace must be established and maintained between yourselves and the neighboring tribes of the red men, and you need in the next place the means of subsistence.

“My Red Children: I thank you for your kind wishes for me personally, and as President of the United States.

“While I am in office, I shall use my influence to keep you at peace with the Sioux, between whom and the Chippewas there has always been a most deadly hostility, fatal to the prosperity of both nations. I shall also recommend that you be provided with the means of raising corn and the other necessaries of life.

“My Red Children: I hope that you have met with success in your present visit, and that you may return to your homes without an accident by the way; and I bid you say to your red brethren that I cordially wish them health and prosperity. Farewell.”

This interesting interview closed with a general shaking of hands and during the addresses, it is creditable to the parties to say, that the feelings were reached. Tears glistened in the eyes of the Indians and General Taylor evinced sufficient emotion, during the address of the chief, to show that he possesses a heart that may be touched. The old veteran was heard to remark, as the delegation left the room, “What fine looking men they are!”

Major Martell, the half-breed interpreter, acquitted himself handsomely throughout. The Indians came away declaring that “General Taylor talked very good.”

The General’s family and suite, evidently not prepared for the visit; were not dressed to receive company at so early an hour; nevertheless, they soon came in, en dishabille, and looked on with interest.

P.

One of the lingering questions I’ve had about the 1848-49 Delegation has been whether or not the Ojibwe leadership viewed it as a success. This document shows that the answer was unequivocally yes. It also shows why the chiefs felt so blindsided and disbelieving in the spring of 1850 when the government agents at La Pointe told them that Taylor had ordered them to remove. They didn’t have to go back to 1842 for the Government’s promises. They had heard them only a year earlier from both the president and the president-elect!

It also explains why during and after the removal, the chiefs number-one priority was sending another delegation. One would eventually go in 1852, led by Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. This would help secure the reservations sought by the first delegation, but that was only after two failed removal attempts and hundreds of deaths.

If the cholera epidemic had not come, Chief Buffalo and other prominent chiefs, would have likely gone back to Taylor in the winter of 1849-50. They may have been able to secure new treaty negotiations, reservations on the ceded territory, or at the very least have been more prepared for the upcoming removal:

George Johnston to Henry Schoolcraft, 5 October 1849, MS Papers of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft: General Correspondence, 1806-1864, BOX 51.

Saut Ste Maries

Oct 5th 1849

My Dear sir,

Your favor of Sep. 14th, I have just now received and will lose no time in answering. Since I wrote to you on the subject of an intended delegation of Chippewa Chiefs desiring to visit the seat of Govt., I visited Lapointe and remained there during the payment, and I had an opportunity of seeing & talking with the chiefs. They held a council with their agent Dr. Livermore and expressed their desire to visit Washington this season, and they laid the matter before him with open frankness, and Dr. Livermore answered them in the same strain, advising them at the same time, to relinquish their intended visit this year, as it would be dangerous for them, to travel in the midst of sickness which was so prevalent & so widely spread in the land, and that if they should still feel desirous to go on the following year that he would then permit them to do so, and that he would have no objections, this appearing so reasonable to the chiefs, that they assented to it.

I will write to the chiefs and express to them the subject of your letter, and direct them to address Mr. Babcock at Detroit.

You will herein find enclosed copy of Mr. Ballander’s letter to me, a gentleman of the Hon. Hudson’s Bay Co. & Chief factor at Fort Garry in the Red river region, it is very kind & his sympathy, devotes a feeling heart.– Mr. Mitchell of Green Bay to whom I have written in the early part of this summer, to make enquiries relative to certain reports of Tanner’s existence among the sioux, he has not as yet returned an answer to may communication and I feel the neglect with some degree of asperity which I cannot control.

Very Truly yours

Geo. Johnston

Henry R. Schoolcraft Esq.

Washington

It is hard to say how differently history may have turned out if a second delegation had been able to go with George Johnston. There is a good chance it would have been a lot more successful. Johnston was much more of an insider than Martell–who had had a lot of difficulty convincing the American authorities of his credentials. One of those who stood in Martell’s way was Henry Schoolcraft. Schoolcraft, was regarded by the American establishment as the foremost authority on Ojibwe affairs and was Johnston’s brother-in-law.

It may not have worked. The inertia of United States Indian Policy was still with removal. Any attempt to reverse Manifest Destiny and convince the government to cede land back to Indian nations east of the Mississippi was going to be an uphill battle. The Minnesota trade interests were strong.

Also, Schoolcraft was a Democrat, so he would have had less influence with the Whig Taylor–though agreements on Western issues sometimes crossed party lines. However, one can imagine George Johnston sitting around a table in Washington with his “Uncle” Buffalo, his brother-in-law Schoolcraft, and the U.S. President, working out the contours of a new treaty avoiding the removal entirely. Because of the cholera, however, we’ll never know.

For more on how the fallout from the Mexican War impacted Ojibwe removal, see Slavery, Debt Default, and the Sandy Lake Tragedy

For more on the 1848-49 Delegation, see: this post, this post, and this post

When we die, we will lay our bones at La Pointe.

March 20, 2024

By Leo

From individual historical documents, it can be hard to sequence or make sense of the efforts of the United States to remove the Lake Superior Ojibwe from ceded territories of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan in the years 1850 and 1851. Most of us correctly understand that the Sandy Lake Tragedy was caused an alliance of government and trading interests. Through greed, deception, racism, and callous disregard for human life, government officials bungled the treaty payment at Sandy Lake on the Mississippi River in the fall and winter of 1850-51, leading to hundreds of deaths. We also know that in the spring of 1852, Chief Buffalo and a delegation of La Pointe Ojibwe chiefs travelled to Washington D.C. to oppose the removal. It is what happened before and between those events, in the summers of 1850 and 1851, where things get muddled.

Confusion arises because the individual documents can contradict our narrative. A particular trader, who we might want to think is one of the villains, might express an anti-removal view. A government agent, who we might wish to assign malicious intent, instead shows merely incompetence. We find a quote or letter that seems to explain the plans and sentiments leading to the disaster at Sandy Lake, but then we find the quote is dated after the deaths had already occurred.

Therefore, we are fortunate to have the following letter, written in November of 1851, which concisely summarizes the events up to that point. We are even more fortunate that the letter is written by chiefs, themselves. It is from the Office of Indian Affairs archives, but I found a copy in the Theresa Schenck papers. It is not unknown to Lake Superior scholarship, but to my knowledge it has not been reproduced in full.

The context is that Chief Buffalo, most (but not all) of the La Pointe chiefs, and some of their allies from Ontonagon, L’Anse, Upper St. Croix Lake, Chippewa River and St. Croix River, have returned to La Pointe. They have abandoned the pay ground at Fond du Lac in November 1851, and returned to La Pointe. This came after getting confirmation that the Indian Agent, John S. Watrous, has been telling a series of lies in order to force a second Sandy Lake removal–just one year removed from the tragedy. This letter attempts to get official sanction for a delegation of La Pointe chiefs to visit Washington. The official sanction never came, but the chiefs went anyway, and the rest is history.

La Pointe, Lake Superior, Nov. 6./51

To the Hon Luke Lea

Commissioner of Indian Affairs Washington D.C.

Our Father,

We send you our salutations and wish you to listen to our words. We the Chiefs and head men of the Chippeway Tribe of Indians feel ourselves aggrieved and wronged by the conduct of the U.S. Agent John S. Watrous and his advisors now among us. He has used great deception towards us, in carrying out the wishes of our Great Father, in respect to our removal. We have ever been ready to listen to the words of our Great Father whenever he has spoken to us, and to accede to his wishes. But this time, in the matter of our removal, we are in the dark. We are not satisfied that it is the President that requires us to remove. We have asked to see the order, and the name of the President affixed to it, but it has not been shewn us. We think the order comes only from the Agent and those who advise with him, and are interested in having us remove.

Kicheueshki. Chief. X his mark

Gejiguaio X “

Kishkitauʋg X “

Misai X “

Aitauigizhik X “

Kabimabi X “

Oshoge, Chief X “

Oshkinaue, Chief X “

Medueguon X “

Makudeua-kuʋt X “

Na-nʋ-ʋ-e-be, Chief X “

Ka-ka-ge X “

Kui ui sens X “

Ma-dag ʋmi, Chief X “

Ua-bi-shins X “

E-na-nʋ-kuʋk X “

Ai-a-bens, Chief X “

Kue-kue-Kʋb X “

Sa-gun-a-shins X “

Ji-bi-ne-she, Chief X “

Ke-ui-mi-i-ue X “

Okʋndikʋn, Chief X “

Ang ua sʋg X “

Asinise, Chief X “

Kebeuasadʋn X “

Metakusige X “

Kuiuisensish, Chief X “

Atuia X “

Gete-kitigani[inini? manuscript torn]

L. H. Wheeler

We the undersigned, certify, on honor, that the above document was shown to us by the Buffalo, Chief of the Lapointe band of Chippeway Indians and that we believe, without implying and opinion respecting the subjects of complaint contained in it, that it was dictated by, and contains the sentiments of those whose signatures are affixed to it.

S. Hall

C. Pulsifer

H. Blatchford

When I started Chequamegon History in 2013, the WordPress engine made it easy to integrate their features with some light HTML coding. In recent years, they have made this nearly impossible. At some point, we’ll have to decide whether to get better at coding or overhaul our signature “blue rectangle” design format. For now, though, I can’t get links or images into the blue rectangles like I used to, so I will have to list them out here:

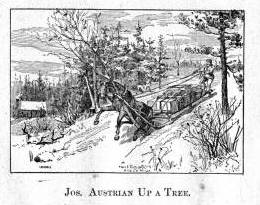

Joseph Austrian’s description of the same

Boutwell’s acknowledgement of the suspension of the removal order, and his intent to proceed anyway

Chequamegon History has looked into the “Great Father” fur trade theater language of ritual kinship before in our look at Blackbird’s speech at the 1855 Payment. You may have noticed Makadebines (Blackbird) didn’t sign this letter. He was working on a different plant to resist removal. Look for a related post soon.

If you’re really interested in why the president was Gichi-noos (Great Father), read these books:

Watrous, and many of the Americans who came to the Lake Superior country at this time, were from northeastern Ohio. Watrous was able to obtain and keep his position as agent because his family was connected to Elisha Whittlesey.

In the summer and fall of 1851, Watrous was determined to get soldiers to help him force the removal. However, by that point, Washington was leaning toward letting the Lake Bands stay in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Last spring, during one of the several debt showdowns in Congress, I wrote on how similar antics in Washington contributed to the disaster of 1850. My earliest and best understanding of the 1850-1852 timeline, and the players involved, comes from this book:

We know that Kishkitauʋg (Cut Ear), and Oshoge (Heron) went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852. Benjamin Armstrong’s account is the most famous, but the delegation’s other interpreter, Vincent Roy Jr., also left his memories, which differ slightly in the details.

One of my first posts on the blog involved some Sandy Lake material in the Wheeler Family Papers, written by Sherman Hall. Since then, having seen many more of their letters, I would change some of the initial conclusions. However, I still see Hall as having committing a great sin of omission for not opposing the removal earlier. Even with the disclaimer, however, I have to give him credit for signing his name to the letter this post is about. Although they shared the common goal of destroying Ojibwe culture and religion and replacing it with American evangelical Protestantism, he A.B.C.F.M. mission community was made up of men and women with very different personalities. Their internal disputes were bizarre and fascinating.

Wheeler Papers: 1854 La Pointe before the Treaty

August 7, 2017

By Amorin Mello

Selected letters from the

Wheeler Family Papers,

Box 3, Folders 11-12; La Pointe County.

Crow-wing, Min. Ter.

Jan. 9th 1854

Brother Wheeler,

Reverend Leonard Hemenway Wheeler ~ In Unnamed Wisconsin by Silas Chapman, 1895, cover image.

Though not indebted to you just now on the score of correspondence, I will venture to intrude upon you a few lines more. I will begin by saying we are all tolerably well. But we are somewhat uncomfortable in some respects. Our families are more subject to colds this winter than usual. This probably may be attributed in part at least to our cold and open houses. We were unable last fall to do any thing more than fix ourselves temporarily, and the frosts of winter find a great many large holes to creep in at. Some days it is almost impossible for us to keep warm enough to be comfortable.

Our prospects for accomplishing much for the Indians here I do not think look more promising than they did last fall. There are but few Indians here. These get drunk every time they can get whiskey, of which there is an abundance nearby. Among the white people here, none are disposed to attend meetings much except Mr. [Welton?]. He and his wife are discontented and unhappy here, and will probably get away as soon as they can. We hear not a word from the Indian Department. Why they are minding us in this manner I cannot tell. But I should like it much better, if they would tell us at once to be gone. I have got enough of trying to do anything for Indians in connection with the Government. We can put no dependence upon any thing they will do. I have tried the experiment till I am satisfied. I think much more could be done with a boarding school in the neighborhood of Lapointe than here And my opinion is, that since things have turned out as they have here, we had better get out of it as soon as we can. With such an agent as we now have, nothing will prosper here. He is enough to poison everything, and will do more moral evil in such a community, as this, than a half a dozen missionaries can do good. My opinion is, that if they knew at Washington how things are and have been managed here, there would be a change. But I do not feel certain of this. For I sometimes am tempted to adopt the opinion that they do not care much there how things go here. But should there be a change, I have little hope that is would would make things materially better. The moral and social improvement of the Indians, I fear, has little to do with the appointment of agents and superintendents. I do not think I ought to remain here very long and keep my family here, as things are now going. If we were not involved with the Government with regard to the school matter, I would advise the Committee to quit here as soon as we can find a place to go to. My health is not very good. The scenes, and labors and attacks of sickness which I have passed through during the past two years have made almost a wreck of my constitution. It might rally under some circumstances. But I do not think it will while I stay here, so excluded from society, and so harassed with cares and perplexities as I have been and as I am likely to be in future, should we go on and try to get up a school. My wife is in no better spirits than I am. She has had several quite ill turns this winter. the children all wish to get away from here, and I do not know that I shall have power to keep them here, even if I am to stay.

But what to do I do not know. The Committee say they do not wish to abandon the Ojibwas. I cannot in future favor the removal of the lake Indians. I believe that all the aid they will receive from the Government will never civilize or materially benifit them. I judge from the manner in which things have been managed here. Our best hope is to do what we can to aid them where they are to live peaceably with the whites, and to improve and become citizens. The idea of the Government sending infidels and heathens here to civilize and Christianize the Indians is rediculous.

I always thought it doubtful whether the experiment we are trying would succeed. In that case it was my intention to remove somewhere below here, and try to get a living, either by raising my potatoes or by trying to preach to white people, or by uniting both. but I do not hardly feel strong enough to begin entirely anew in the wilderness to make me a home. I suppose my family would be as happy at Lapointe, as they would any where in the new and scattered settlements for fifty or a hundred miles below here. And if thought I could support myself then, I might think of going back there. There are our old friends for whose improvement we have laborred so many years. I feel almost as much attachment for them as for my won children. And I do not think they ought to be left like sheep upon the mountains without a shepherd. And if the Board think it best to expend money and labor for the Ojibwas, they had better expend it there than here, as things now are at least. I think we were exerting much much more influence there before we left, then we have here or are likely to exert. I have no idea that the lake Indians will ever remove to this place, or to this region.

Reverend Sherman Hall

~ Madeline Island Museum

What do you think of recommending to the Board to day to exert a greater influence on the people in the neighborhood of Lapointe[?/!] I feel reluctant to give up the Indians. And if I could get a living at Lapointe, and could get there, I should be almost disposed to go back and live among those few for whom I have labored so long, if things turn out here as I expect they will. I have not much funds to being life with now, nor much strength to dig with. But still I shall have to dig somewhere. The land is easier tilled in this region than that about the lake. But wood is more scarce. My family do not like Minesota. Perhaps they would, if they should get out of the Indian country. Edwin says he will get out of it in the spring, and Miles says he will not stay in such a lonesome place. I shall soon be alone as to help from my children. My boys must take care of themselves as soon as they arrive at a suitable age, and will leave me to take care of myself. We feel very unsettled. Our affairs here must assume a different aspect, or we cannot remain here many months longer. Is there enough to do at Lapointe; or is there a prospect that there will soon be business to draw people enough then, to make it an object to try to establish the institution of the gospel there? Write me and let me know your views on such subjects as these.

[Unsigned, but appears to be from Sherman Hall]

Crow-wing Feb. 10th 1854

Brother Wheeler:

I received your letter of jan. 16th yesterday, and consequently did not sleep as much as usual last night. We were glad to hear that you are all well and prosperous. We too are well which we consider a great blessing, as sickness in present situation would be attended with great inconvenience. Our house is exceedingly cold and has been uncomfortable during some of the severe cold weather have had during the last months. Yet we hope to get through the winter without suffering severely. In many respects our missionary spirit has been put to a severer test than at any previous time since we have been in the Indian country, during the past year. We feel very unsettled, and of course somewhat uneasy. The future does not look very bright. We cannot get a word from the Indian Department whether we may go on or not. If we cannot get some answer from them before long I shall be taking measures to retire. We have very little to hope, I apprehend, from all the aid the Government will render to words the civilization and moral and intellectual improvement of the Indians. For missionaries or Indians to depend on them, is to depend on a broken staff.

~ Minnesota Historical Society

“The American Fur Company therefore built a ‘New Fort’ a few miles farther north, still upon the west shore of the island, and to this place, the present village, the name La Pointe came to be transferred. Half-way between the ‘Old fort’ and the ‘New fort,’ Mr. Hall erected (probably in 1832) ‘a place for worship and teaching,’ which came to be the centre of Protestant missionary work in Chequamegon Bay.”

~ The Story of Chequamegon Bay

I do not see that our house is so divided against itself, that it is in any great danger of falling at present. My wife never did wish to leave Lapointe and we have ever, both of us, thought that the station ought not to be abandoned, unless the Indians were removed. But this seemed not to be the opinion of the committee or of our associates, if I rightly understood them. I had a hard struggle in my mind whether to retire wholly from the service of the Board among the Indians, or to come here and make a further experiment. I felt reluctant to leave them, till we had tried every experiment which held out any promise of success. When I remove my family here our way ahead looked much more clear than it does now. I had completed an arrangement for the school which had the approval of Gov. Ramsey, and which fell through only in consequence of a little informality on his part, and because a new set of officers just then coming into power must show themselves a little wiser than their predecessors. Had not any associates come through last summer, so as to relieve me of some of my burdens and afford some society and counsel in my perplexities I could not have sustained the burden upon me in the state of my health at that time. A change of officers here too made quite an unfavorable change in our prospects. I have nothing to reproach myself with in deciding to come here, nor in coming when we did, though the result of our coming may not be what we hoped it would be. I never anticipated any great pleasure in being connected with a school connected in any way with the Government, nor did I suppose I should be long connected with it, even if it prospered. I have made the effort and now if it all falls, I shall feel that Providence has not a work for us to do here. The prospects of the Indians look dark, what is before me in the future I do not know. My health is not good, though relief from some of the pressure I had to sustain for a time last fall and the cold season has somewhat [?????] me for the time being. But I cannot endure much excitement, and of course our present unsettled affairs operate unfavorably upon it. I need for a time to be where I can enjoy rest from everything exciting, and when I can have more society that I have here, and to be employed moderately in some regular business.

Antoine Gordon [Gaudin]

~ Noble Lives of a Noble Race by the St. Mary’s Industrial School (Bad River Indian Reservation), 1909, page 207.

Charles Henry Oakes

~ Findagrave.com

As to your account I have not had time to examine it, but will write you something about it by & by. As to any account which Antoine Gaudin has against me, I wish you would have him send it to me in detail before you pay it. I agreed with Mr. Nettleton to settle with him, and paid him the balance due to Antoine as I had the account. I suppose he made the settlement, when he was last at Lapointe. As to the property at Lapointe, I shall immediately write to Mr. Oakes about it. But I suppose in the present state of affairs, it will be perhaps, a long time before it will be settled so as to know who does own it. It is impossible for me to control it, but you had better keep posession of it at present. I cannot send Edwin [??] through to cultivate the land & take care of it. He will be of age in the spring, and if he were to go there I must hire him. He will probably leave us in the spring. Please give my best regards to all. Write me often.

Yours truly

S. Hall

Crow-wing, Min. Ter.

Feb. 21st 1854

Brother Wheeler,

Paul Hudon Beaulieu

~ FamilySearch.org

I wrote you a few days ago, and at the same time I wrote to Mr. Oakes inquiring whether he had got possession of the Lapointe property. I have not yet got a reply from him, but Mr. Beaulieu tells me that he heard the same report which you mentioned in your letter, and that he inquired of Mr. Oakes about it when he saw him on a recent visit to St. Paul, and finds that it is all a humbug. Oakes has nothing to do with it. Mr. Beaulieu said that the sale of last spring has been confirmed, and that Austrian will hold Lapointe. So farewell to all the inhabitants’ claims then, and to anything being done for the prosperity of the peace for the present, unless it gets out of his hands.

I have written to Austrian to try to get something for our property if we can. But I fear there is not much hope. If he goes back to Lapointe in the spring, do the best you can to make him give us something. I feel sorry for the inhabitants there that they are left at his mercy. He may treat them fairly, but it is hardly to be expected.

Clement Hudon Beaulieu

~ TreatiesMatter.org

As to our affairs here, there has been no particular change in their aspects since I wrote a few days ago. There must be a crisis, I think, in a few weeks. We must either go on or break up, I think, in the spring. We are trying to get a decision. I understand our agent has been threatened with removal if he carries on as he has done. I believe there is no hope of reformation in his case, and we may get rid of him. Perhaps God sent us here to have some influence in some such matters, so intimately connected with the welfare of the Indians. I have never thought I [????] can before I was sent in deciding to come here. Some trials and disappointments have grown out of my coming, but I feel conscious of having acted in accordance with my convictions of duty at this time.

If all falls through, I know not what to do in the future. The Home Missionary Society have got more on their hands now than they have funds to pay, if I were disposed to offer myself to labor under them. I may be obliged to build me a shanty somewhere on some little unoccupied piece of land and try to dig out a living. In these matters the Lord will direct by his providence.

You must be on your guard or some body will trip you up and get away your place. There are enough unprincipled fellows who would take all your improvements and send you and all the Indians into the Lake if they could make a dollar by it. I should not enlarge much, without getting a legal claim to the land. Neither would I advise you to carry on more family than is necessary to keep what team you must have, and to supply your family with milk and vegetables. It will be advantage/disadvantage to you in a pecuniary point of view, it will load you with and tend to make you worldly minded, and give your establishment the air of secularity in the eyes of the world. If I were to go back again to my old field, I would make my establishment as small as I could & have enough to live comfortable. I with others have thought that your tendency was rather towards going to largely into farming. I do not say these things because I wish to dictate or meddle with your affairs. Comparing views sometimes leads to new investigations in regard to duty.

May the Lord bless you and yours, and give you success and abundant prosperity in your labours of love and efforts to Save the Souls around you.

Give my best regards to Mrs. W., the children, Miss S and all.

Yours truly,

S. Hall

I forgot to say that we are all well. Henry and his family have enjoyed better health here, then they used to enjoy at Lapointe.

Feb 27

Brother Wheeler.

My delay to answer your note may require an explanation. I have not had time at command to attend to it conveniently at an earlier period. As to your first questions. I suppose there will be no difference of opinion between us as to the correctness of the following remarks.

- The Gospel requires the members of a church to exercise a spirit of love, meekness and forbearance towards an offending brother. They are not to use unnecessary severity in calling him to account for his errors. Ga. 6:1.

- The Object of Church discipline is, not only to [pursue/preserve?] the Church pure in doctrine & morals, that the contrary part may have no evil thing to say of them; but also to bring the offender to a right State of mind, with regard this offense, and gain him back to duty and fidelity.

- If prejudice exist in the mind of the offender towards his brethren for any reason, the spirit of the gospel requires that he be so approached if possible as to allay that prejudice, otherwise we can hardly expect to gain a candid hearing with him.

Charles William Wulff Borup, M.D. ~ Minnesota Historical Society

I consider that these remarks have some bearing on the case before us. If it was our object to gain over Dr. B. to our views of the Sabbath, and bring him to a right State of mind with regard this Sabbath breaking, the manner of approaching him would have, in my view, much to do with the offence. He may be approached in a Kind and [forbearing?] manner, when one of sternness and dictation will only repel him from you. I think we ought, if possible, and do our duty, avoid a personal quarrel with him. To have brought the subject before the Church & made a public affair of it, before [this/then?] and more private means have been tried to get satisfaction, would, I am sure, have resulted in this. I found from my own interviews with him, that there was hope, if the rest of the brethren would pursue a similar course. I felt pretty sure they would obtain satisfaction. IF they had [commenced?] by a public prosecution before the church, it would only have made trouble without doing any good. The peace of our whole community would have been disturbed. I thought one step was gained when I conversed with him, and another when you met him on the subject. I knew also that prejudices existed both in his mind towards us, & in our minds towards him which were likely to affect the settlement of this affair, and which as I thought, would be much allayed by individuals going to him and speaking face to face on this subject in private. He evidently expected they would do so. Mutual conversations and explanations allay these feelings very much. At least it has been so in my experience.

As to your second question. I do not say that it was Mr. Ely’s duty to open the subject to Doc. Borup at the preparatory lecture. If he had done so, it would have been only a private interview; for there [was?] not enough present to transact business. All I meant to affirm respecting that occasion is, that it afforded a good opportunity to do so, if he wishes, and that Dr. B. expected he would have done so, as I afterwards learnt, if he has any objection to make against his coming to the communion.

As to your third question. I have no complaint to make of the church, that I have urged them to the performance of any “duties“ in this case they have refused to perform.

And now permit me to ask in my turn.

What “duties” have they urged me to perform in this case, which I “have been unwilling, or manifested a reluctance to perform?”

Did you intend by anything which wrote to me or said verbally, to request me to commence a public prosecution of Doc. Borup before the Church?

Will you have the goodness to state in writing, the substance of what you said to me in your study as to your opinion and that of others suspecting my delinquency in maintaining church discipline.

A reply to these questions would be gratefully received.

Your brother in Christ

S. Hall

Crow Wing. March 12th 1854

Brother Wheeler:

Your letter of Feb 17th came to hand by our last mail; and though I wrote you but a short time ago, I will say a few words in relation to one or two topics to which you allude. Shortly after I received your former letter I wrote to Mr. Oakes enquiring about the property at Lapointe. In reply, says that himself and some others purchased Mr. Austrian’s rights at Lapointe of Old Hughes on the strength of a power of attorney which he held. Austrian asserts the power of attorney to be fraudulent, and that they cannot hold the property. Oakes writes as if he did not expect to hold it. Some time ago I wrote to Mr. Austrian on the same subject, and said to him that if I could get our old place back, I might go back to Lapointe. He says in reply —

Julius Austrian

~ Madeline Island Museum

“I should feel much gratified to see you back at Lapointe again, and can hold out to you the same inducements and assurances as I have done to all other inhabitants, that is, I shall be at Lapointe early in the spring and will have my land surveyed and laid out into lots, and then I shall be ready to give to every one a deed for the lot he inhabits, at a reasonable price, not paying me a great deal more than cost trouble, and time. But with you, my dear Sir, will be no trouble, as I have always known you a just and upright man, and have provided ways to be kind towards us, therefore take my assurance that I will congratulate myself to see you back again; and it shall not be my fault if you do not come. If you come to Lapointe, at our personal interview, we will arrange the matter no doubt satisfactory.”

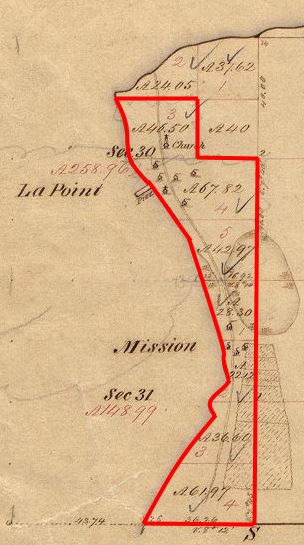

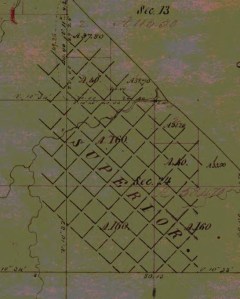

“The property” from the James Hughes Affair is outlined in red. This encompassed the Church at La Pointe (New Fort) and the Mission (Middleport) of Madeline Island. 1852 PLSS survey map by General Land Office.

I suppose Austrian will hold the property and probably we shall never realize anything for our improvements. You must do the best you can. Make your appeal to his honor, if he has any. It will avail nothing to reproach him with his dishonesty. I do not know what more I can do to save anything, or for any others whose property is in like circumstances with ours.

You speak discouragingly of my going back to Lapointe. I do not think the Home Miss. Soc. would send a missionary there only for the few he could reach in the English language. If the people want a Methodist, encourage them to get one. It is painful to me to see the place abandoned to irreligion and vices of every Kind, and the labours I have expended there thrown away. I can hardly feel that it was right to give up the station when we did. If I thought I could support myself there by working one half the time and devoting the rest to ministerial labors for the good of those I still love there, I should still be willing to go back, if could get there & had a shelter for my head, unless there is a prospect of being more useful here. But the land at Lapointe is so hard to subdue that I am discouraged about making an attempt to get a living there by farming. I am not much of a fisherman. There is some prospect that we may be allowed to go on here. Mr. Treat has been to Washington, and says he expects soon to get a decision from the Department. We have got our school farm plowed, and the materials are drawn out of the woods for fencing it. If I have no orders to the contrary, I intend to go on & plant a part of it, enough to raise some potatoes. We may yet get our school established. If we can go ahead, I shall remain here, but if not, I think it is not my duty to remain here another year, as I have the past. In other circumstances, I could do more towards supporting myself and do more good probably.

I have felt much concerned for the people of Lapointe and Bad River on account of the small pox. May the Lord stay this calamity from spreading among you. Write us every mail and tell us all. It is now posted here today that the Old Chief [Kibishkinzhugon?] is dead. I hardly credit the report, though I should suppose he might be one of the first victims of the disease.

I can write no more now. We are all very well now. Give my love to all your family and all others.

Tell Robert how the matters stands about the land. It stands him in how to be on good terms with the Jew just now.

Yours truly,

S. Hall

The snow is nearly all off the ground and the weather for two or three weeks has been as mild as April.

Crow Wing M.H. Apr. 1 1854

Dear Br. & Sr. Wheeler.

I have received a letter from you since I wrote to you & am therfore in your debt in that matter. I have also read your letters to Br. & Sr. Welton I suppose you have received my letter of the 13th of Feb. if so, you have some idea of our situation & I need say no more of that now; & will only say that we are all well as usual & have been during the winter. Mrs. P_ is considerably troubled with her old spinal difficulty. She has got over her labors here last summer * fall. Harriet is not well I fear never will be, because the necessary means are not likely to be used, she has more or less pain in her back & side all the time, but she works on as usual & appears just as she did at LaPointe, if she could be freed from work so as to do no more than she could without injury & pursue uninterruptedly & proper medical course I think she might regain pretty good health. (Do not, any of you, send back these remarks it would not be pleasing to her or the family.) We have said what we think it best to say) –

Br. Hall is pretty well but by no means the vigorous man he once was. He has a slight – hacking cough which I suppose neither he nor his family have hardly noticed, but Mrs. P_ says she does not like the sound of it. His side troubles him some especially when he is a good deal confined at writing. Mr. & Mrs. W_ are in usual health. Henry’s family have gone to the bush. They are all quite well. He stays here to assist br. H_ in the revision & keeps one or two of his children with him. They are now in Hebrews, with the Revision. Henry I suppose still intends to return to Lapointe in the spring. –

Now, you ask, in br. Welton’s letter, “are you all going to break up there in the spring.” Not that I know of. It would seem to me like running away rather prematurely. When the question is settled, that we can do nothing here, then I am willing to leave, & it may be so decided, but it is not yet. We have not had a whisper from Govt. yet. Wherefore I cannot say.

It looks now as if we must stay this season if no longer. Dr. Borup writes to br. Hall to keep up good courage, that all will come out right by & by, that he is getting into favor with Gov. Gorman & will do all he can to help us. (Br. Hall’s custom is worth something you know).

Henry C. Gilbert

~ Branch County Photographs

By advise of the Agent, we got out (last month) tamarack rails enough to fence the school farm (which was broke last summer) of some 80 acres & it will be put up immediately. Our great father turned out the money to pay for the job. These things look some like our staying awhile I tell br H_ I think we had better go as far as we can, without incurring expense to the Board (except for our support) & thus show our readiness to do what we can. if we should quit here I do not know what will be done with us. Br Hall would expect to have the service of the Board I suppose. Should they wish us to return to Bad River we should not say nay. We were much pleased with what we have heard of your last fall’s payment & I am as much gratified with the report of Mr. H. C. Gilbert which I have read in the Annual Report of the Com. of Indian Affairs. He recommends that the Lake Superior Indians be included in his Agency, that they be allowed to remain where they are & their farmers, blacksmith & carpenter be restored to them. If they come under his influence you may expect to be aided in your efforts, not thwarted , by his influence. I rejoice with you in your brightening prospects, in your increased school (day & Sabbath) & the increased inclination to industry in those around you. May the lord add his blessing, not only upon the Indians but upon your own souls & your children, then will your prosperity be permanent & real. Do not despise the day of small things, nor overlook especially neglect your own children in any respect. Suffer them not to form idle habits, teach them to be self reliant, to help themselves & especially you, they can as well do it as not & better too, according to their ability & strength, not beyond it, to fear God & keep his commandments & to be kind to one another (Pardon me these words, I every day see the necessity of what I have said.) We sympathize with you in your situation being alone as you are, but remember you have one friend always near who waits to [commence?] with you, tell Him & all with you from Abby clear down to Freddy.

Affectionately yours

C. Pulsifer

Write when you can.

Crow wing Min. Ter.

April 3d 1854

Brother Wheeler

George E. Nettleton and his brother William Nettleton were pioneers, merchants, and land speculators at what is now Duluth and Superior.

~ Image from The Eye of the North-west: First Annual Report of the Statition of Superior, Wisconsin by Frank Abial Flower, 1890, page 75.

Since I wrote you a few days ago, I have received a letter from Mr. G. E. Nettleton, in which he says, that when he was at Lapointe in December last, he was very much hurried and did not make a full settlement with Antoine. He says further, that he showed him my account, and told him I had settled with him, and that he would see the matter right with Antoine. A. replied that all was right. I presume therefore all will be made satisfactory when Mr. N. comes up in the Spring, and that you will have need to make yourself no further trouble about this matter.

I have also received a short note from Mr. Treat in which he says,

“I have not replied to your letters, because I have been daily expecting something decisive from Washington. When I was there, I had the promise of immediate action; but I have not heard a word from them”.

“I go to Washington this Feb, once more. I shall endeavor to close up the whole business before I return. I intend to wait till I get a decision. I shall propose to the Department to give up the school, if they will indemnify us. If I can get only a part of what we lose, I shall probably quit the concern”.

Thus our business with the Government stood on March the 9th, I have lost all confidence in the Indian Department of our Government under this administration, to say nothing of the rest of it. If the way they have treated us is an index to their general management, I do not think they stand very high for moral honesty. The prospects for the Indians throughout all our territories look dark in the extreme. The measures of the Government in relation to them are not such as will benefit and save many of them. They are opening the floodgates of vice and destruction upon them in every quarter. The most solemn guarantees that they shall be let alone in the possession of domains expressly granted them mean nothing.

Our prospects here look dark. For some time past I have been rather anticipating that we should soon get loose and be able to go on. But all is thrown into the dark again. What I am to do in future to support my family, I do not know. If we are ordered to quit here and turn over the property, it would turn [illegible] out of doors.

Mr. Austrian expects us back to Lapointe in the Spring & Mr. Nettleton proposes to us to go to Fond du Lac, (at the Entry). He says there will be a large settlement then next season. A company is chartered to build a railroad through from the Southern boundary of this territory to that place. It is probable that Company [illegible] will make a grant of land for that purpose. If so, it will probably be done in a few years. That will open the lake region effectually. I feel the need of relaxation and rest before I do anything to get established anywhere.

We are still working away at the Testament, it is hard work, and we make lately but slow progress. There is a prospect that the Bible Society will publish it but it is not fully decided. I wish I could be so situated that I could finish the grammar.

But I suppose I am repeating what I have said more than once before. We are generally in good health and spirits. We hope to hear from by next mail.

Yours truly

S. Hall

What do you think about the settlements above Lapointe and above the head of the Lake?

Detroit July 10th 1854

Rev. Dr. Bro.

At your request and in fulfilment of my promise made at LaPointe last fall so after so long a time I write: And besides “to do good & to communicate” as saith the Apostle “forget not, for with such sacrifices God is well pleased.”

We did not close up our Indian payments of last year until the middle of the following January, the labors, exposures and excitements of which proved too much for me and I went home to New York sick & nearly used up about the last of February & continued so for two months. I returned here about a week ago & am now preparing for the fall pay’ts.

The Com’sr. has sent in the usual amounts of Goods for the LaPointe Indians to Mr. Gilbert & I presume means to require him to make the payment at La P. that he did last fall, although we have received nothing from the Dep’t. on the subject.

“George Washington Manypenny (1808-1892) was the Director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs of the United States from 1853 to 1857.”

~ Wikipedia.org

In regard to the Treaty with the Chipp’s of La Sup’r & the Miss’i, the subject is still before Congress and if one is made this fall it has been more than intimated that Com’r Manypenny will make it himself, either at LaP’ or at F. Dodge or perhaps at some place farther west. Of course I do not speak from authority or any of the points mentioned above, for all is rumour & inference beyond the mere arrival here of the Goods to Mr G’s care.

From various sources I learn that you have passed a severe winter and that much sickness has been among the Indians and that many of them have been taken away by the Small Pox.

This is sad and painful intelligence enough and I can but pray God to bless & overrule all to the goods of his creasures and especially to the Missionaries & their families.

Notwithstanding I have not written before be assured that I have often [???] of and prayed for you and yours and while in [Penn.?] you made your case my own so far as to represent it to several of our Christian brethren and the friends of missions there and who being actuated by the benevolent principles of the Gospel, have sent you some substanted relief and they promise to do more.

The Elements of the political world both here and over the waters seem to be in fearful & [?????] commotion and what will come of it all none but the high & holy one can know. The anti Slavery Excitement with us at the North and the Slavery excitement at the South is augmenting fact and we I doubt not will soon be called upon to choose between Slavery & freedom.

If I do not greatly misjudge the blessed cause of our holy religion is or seems to be on the wane. I trust I am mistaken, but the Spirit of averice, pride, sensuality & which every where prevails makes me think otherwise. The blessed Christ will reign [recenth-den?] and his kingdom will yet over all prevail; and so may it be.

Let us present to him daily the homage of a devout & grateful heart for his tender mercies [tousward?] and see to it that by his grace we endure unto the end that we may be saved.

My best regards to Mrs. W. to Miss Spooner to each of the dear children and to all the friends & natives to each of whom I desire to be remembered as opportunity occurs.

The good Lord willing I may see you again this fall. If I do not, nor never see you again in this world, I trust I shall see and meet you in that world of pure delight where saints immortal reign.

May God bless you & yours always & ever

I am your brother

In faith Hope & Charity

Rich. M. Smith

Rev Leonard H. Wheeler

LaPointe

Lake Superior

Miss. House Boston

Augt’ 31, 1854

Rev. L. H. Wheeler,

Lake Superior

Dear Brother

Yours of July 31 I laid before the Com’sr at our last meeting. They have formally authorized the transfer of Mr & Mrs Pulsifer to the Lake, & also that of Henry Blatchford.

Robert Stuart was formerly an American Fur Company agent and Acting Superintendent on Mackinac Island during the first Treaty at La Pointe in 1842.

~ Wikipedia.org

In regard to the “claims” their feeling is that if the Govt’ will give land to your station, they have nothing to say as to the quantity. But if they are to pay the usual govt’ price, the question requires a little caution. We are clear that we may authorize you to enter & [???] take up so much land as shall be necessary for the convenience of the [mission?] families; but we do not see how we can buy land for the Indians. Will you have the [fondness?] to [????] [????] on these points. How much land do you propose to take up in all? How much is necessary for the convenience of the mission families?

Perhaps you & others propose to take up the lands with private funds. With that we have nothing to do, so long as you, Mr P. & H. do not become land speculators; of which, I presume, there is no danger.

As to the La Pointe property, Mr Stuart wrote you some since, as you know already I doubt not, and replied adversely to making any bargain with Austrian. I took up the opinion of the Com’sr after receiving your letter of July 31, & they think it the wise course. I hope Mr Stewart will get this matter in some shape in due time.

I will write to him in reference to the Bad River land, asking him to see it once if the gov’ will do any thing.

Affectionate regards to Mrs W. & Miss Spooner & all.

Fraternally Yours

S. B. Treat

P.S. Your report of July 31 came safely to hand, as you will & have seen from the Herald.

The Removal Order of 1849

March 12, 2016

By Amorin Mello

United States. Works Progress Administration:

Chippewa Indian Historical Project Records 1936-1942

(Northland Micro 5; Micro 532)

12th President Zachary Taylor gave the 1849 Removal Order while he was still in office. During 1852, Chief Buffalo and his delegation met 13th President Millard Fillmore in Washington, D.C., to petition against this Removal Order.

~ 1848 presidential campaign poster from the Library of Congress

Reel 1; Envelop 1; Item 14.

The Removal Order of 1849

By Jerome Arbuckle

After the war of 1812 the westward advance of the people of the United States of was renewed with vigor. These pioneers were imbued with the idea that the possessions of the Indian tribes, with whom they came in contact, were for their convenience and theirs for the taking. Any attempt on the part of the aboriginal owners to defend their ancestral homes were a signal for a declaration of war, or a punitive expedition, which invariably resulted in the defeat of the Indians.

“Peace Treaties,” incorporating terms and stipulations suitable particularly to the white man’s government, were then negotiated, whereby the Indians ceded their lands, and the remnants of the dispossessed tribe moved westward. The tribes to the south of the Great Lakes, along the Ohio Valley, were the greatest sufferers from this system of acquisition.

Another system used with equal, if less sanguinary success, was the “treaty system.” Treaties of this type were actually little more than receipt signed by the Indian, which acknowledged the cessions of huge tracts of land. The language of the treaties, in some instances, is so plainly a scheme for the dispossession and removal of the Indians that it is doubtful if the signers for the Indians understood the true import of the document. Possibly, and according to the statements handed down from the Indians of earlier days to the present, Indians who signed the treaties were duped and were the victims of treachery and collusion.

By the terms of the Treaties of 1837 and 1842, the Indians ceded to the Government all their territory lying east of the Mississippi embracing the St. Croix district and eastward to the Chocolate River. The Indians, however, were ignorant of the fact that they had ceded these lands. According to the terms, as understood by them, they were permitted to remain within these treaty boundaries and continue to enjoy the privileges of hunting, fishing, ricing and the making of maple sugar, provided they did not molest their white neighbors; but they clearly understood that the Government was to have the right to use the timber and minerals on these lands.

Entitled “Chief Buffalo’s Petition to the President“ by the Wisconsin Historical Society, the story behind this now famous symbolic petition is actually unrelated to Chief Buffalo from La Pointe, and was created before the Sandy Lake Tragedy. It is a common error to mis-attribute this to Chief Buffalo’s trip to Washington D.C., which occurred after that Tragedy. See Chequamegon History’s original post for more information.

Detail of Benjamin Armstrong from a photograph by Matthew Brady (Minnesota Historical Society). See our Armstrong Engravings post for more information.

Their eyes were opened when the Removal Order of 1849 came like a bolt from the blue. This order cancelled the Indians’ right to hunt and fish in the territory ceded, and gave notification for their removal westward. According to Verwyst, the Franciscan Missionary, many left by reason of this order, and sought a refuge among the westernmost of their tribe who dwelt in Minnesota.

Many of the full bloods, who naturally had a deep attachment for their home soil, refused to budge. The chiefs who signed the treaty were included in this action. They then concluded that they were duped by the Treaty Commissioners and were given a faulty interpretation of the treaty passages. Although the Chippewa realized the futility of armed resistance, those who chose to remain unanimously decided to fight it out. A few white men who were true friends of the Indians, among these was Ben Armstrong, the adopted son of the Head Chief, Buffalo, and he cautioned the Indians against any show of hostility.

At a council, Armstrong prevailed upon the chiefs to make a trip to Washington. Accordingly, preparations for the trip were made, a canoe of special make being constructed for the journey. After cautioning the tribesmen to remain calm, pending their return, they set out for Washington in April, 1852. The party was composed of Buffalo, the head Chief, and several sub-chiefs, one of whom was Oshoga, who later became a noted man among the Chippewa. Armstrong was the interpreter and director of the party. The delegation left La Pointe and proceeded by way of the Great Lakes as far as Buffalo, N. Y., and then by rail to Washington. They stopped at the white settlements along the route and their leader, Mr. Armstrong, circulated a petition among the white people. This petition, which was to be presented to the President, urged that the Chippewa be permitted to remain in their own country and the Removal Order reconsidered. Many signatures were obtained, some of the signers being acquaintances of the President, whose signatures he later recognized.

Despite repeated attempts of arbitrary agents, who were employed by the government to administer Indian affairs, and who endeavored to return them back or discourage the trip, they resolutely persisted. The party arrived at Buffalo, New York, practically penniless. By disposing of some Indian trinkets, and by putting the chief on exhibition, they managed to acquire enough money to defray their expenses until they finally arrived at Washington.

Here it seemed their troubles were to begin. They were refused an audience with those persons who might have been able to assist them. Through the kind assistance of Senator Briggs of New York, they eventually managed to arrange for an interview with President Fillmore.

United States Representative George Briggs was helpful in getting an audience with President Millard Fillmore.

~ Library of Congress

At the appointed time they assembled for the interview and after smoking the peace pipe offered by Chief Buffalo, the “Great White Father” listened to their story of conditions in the Northwest. Their petition was presented and read and the meeting adjourned. President Fillmore, deeply impressed by his visitors, directed that their expenses should be paid by the Government and that they should have the freedom of the city for a week.

![Vincent Roy, Jr., portrait from "Short biographical sketch of Vincent Roy, [Jr.,]" in Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, by Chrysostom Verwyst, 1900, pages 472-476.](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/vincent-roy-jr.jpg?w=219)

Vincent Roy, Jr., was also on this famous trip to Washington, D.C. For more information, see this excerpt from Vincent Roy Jr’s biography.

Their mission was accomplished and all were happy. They had achieved what they sought. An uprising of their people had been averted in which thousands of human lives might have been cruelly slaughtered; so with light hearts they prepared for their homeward trip. Their fare was paid and they returned by rail by way of St. Paul, Minnesota, which was as near as they could get by rail to their homes. From St. Paul they traveled overland, a distance of over two hundred miles, overland. Along the route they frequently met with bands of Chippewa, whom they delighted with the information of the successes of their trip. These groups they instructed to repair to Madeline Island for the treaty at the time stipulated.

Upon their arrival at their own homes, the successes of the delegation was hailed with joy. Runners were dispatched to notify the entire Chippewa nation. As a consequence, many who had left their homes in compliance with the Removal Order now returned.

When the time for the treaty drew near, the Chippewa began to arrive at the Island from all directions. Finally, after careful deliberations, the treaty of 1854 was concluded. This treaty provided for several reservations within the ceded territory. These were Ontonagon and L’Anse, in the present state of Michigan, Lac du Flambeau, Bad River or La Pointe, Red Cliff, and Lac Courte Oreille, in Wisconsin, and Fond du Lac and Grand Portage in Minnesota.

It was at this time that the Chippewa mutually agreed to separate into two divisions, making the Mississippi the dividing line between the Mississippi Chippewa and the Lake Superior Chippewa, and allowing each division the right to deal separately with the Government.

Biographical Sketch of Vincent Roy, Jr.

March 3, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Portrait of Vincent Roy, Jr., from “Short biographical sketch of Vincent Roy,” in Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, by Chrysostom Verwyst, 1900, pages 472-476.

Miscellaneous materials related to Vincent Roy,

1861-1862, 1892, 1921

Wisconsin Historical Society

“Miscellaneous items related to Roy, a fur trader in Wisconsin of French and Chippewa Indian descent including a sketch of his early years by Reverend T. Valentine, 1896; a letter to Roy concerning the first boats to go over the Sault Ste. Marie, 1892; a letter to Valentine regarding an article on Roy; an abstract and sketch on Roy’s life; a typewritten copy of a biographical sketch from the Franciscan Herald, March 1921; and a diary by Roy describing a fur trading journey, 1860-1861, with an untitled document in the Ojibwe language (p. 19 of diary).”

Reuben Gold Thwaites was the author of “The Story of Chequamegon Bay”.

St. Agnes’ Church

205 E. Front St.

Ashland, Wis., June 27 1903

Reuben G. Thwaites

Sec. Wisc. Hist Soc. Madison Wis.

Dear Sir,

I herewith send you personal memories of Hon. Vincent Roy, lately deceased, as put together by Rev. Father Valentine O.F.M. Should your society find them of sufficient historical interest to warrant their publication, you will please correct them properly before getting them printed.

Yours very respectfully,

Fr. Chrysostom Verwyst O.F.M.

~ Proceedings of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Issue 51, 1904, page 71.

~ Biographical Sketch – Vincent Roy. ~

~ J. Apr. 2. 1896 – Superior, Wis. ~

I.

Vincent Roy was born August 29, 1825, the third child of a family of eleven children. His father Vincent Roy Sen. was a halfblood Chippewa, so or nearly so was his mother, Elisabeth Pacombe.1

Three Generations:

I. Vincent Roy

(1764-1845)

II. Vincent Roy, Sr.

(1795-1872)

III. Vincent Roy, Jr.

(1825-1896)