Judge Bell Incidents: King No More

October 16, 2025

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

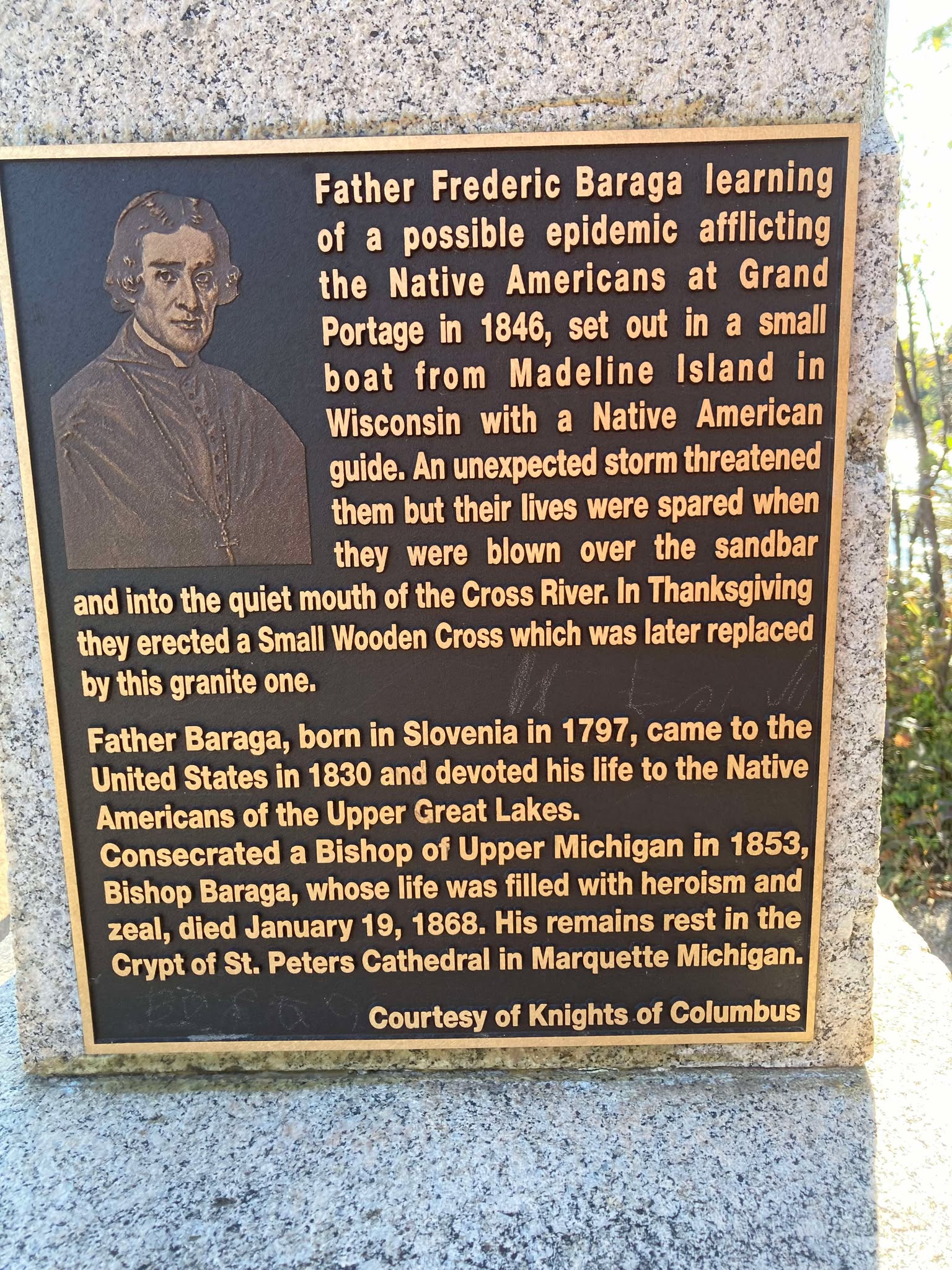

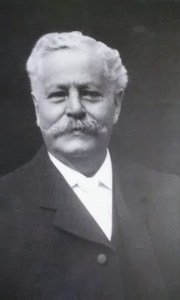

This post is the second of a series featuring newspaper items about La Pointe’s infamous Judge John William Bell. Today we explore obituaries of Judge Bell that described his life at La Pointe. Future posts of this series will feature articles about the late Judge Bell written by his son-in-law George Francis Thomas née Gilbert Fayette Thomas a.k.a G.F.T.

… continued from King of the Apostle Islands.

King of the Apostle Islands No More

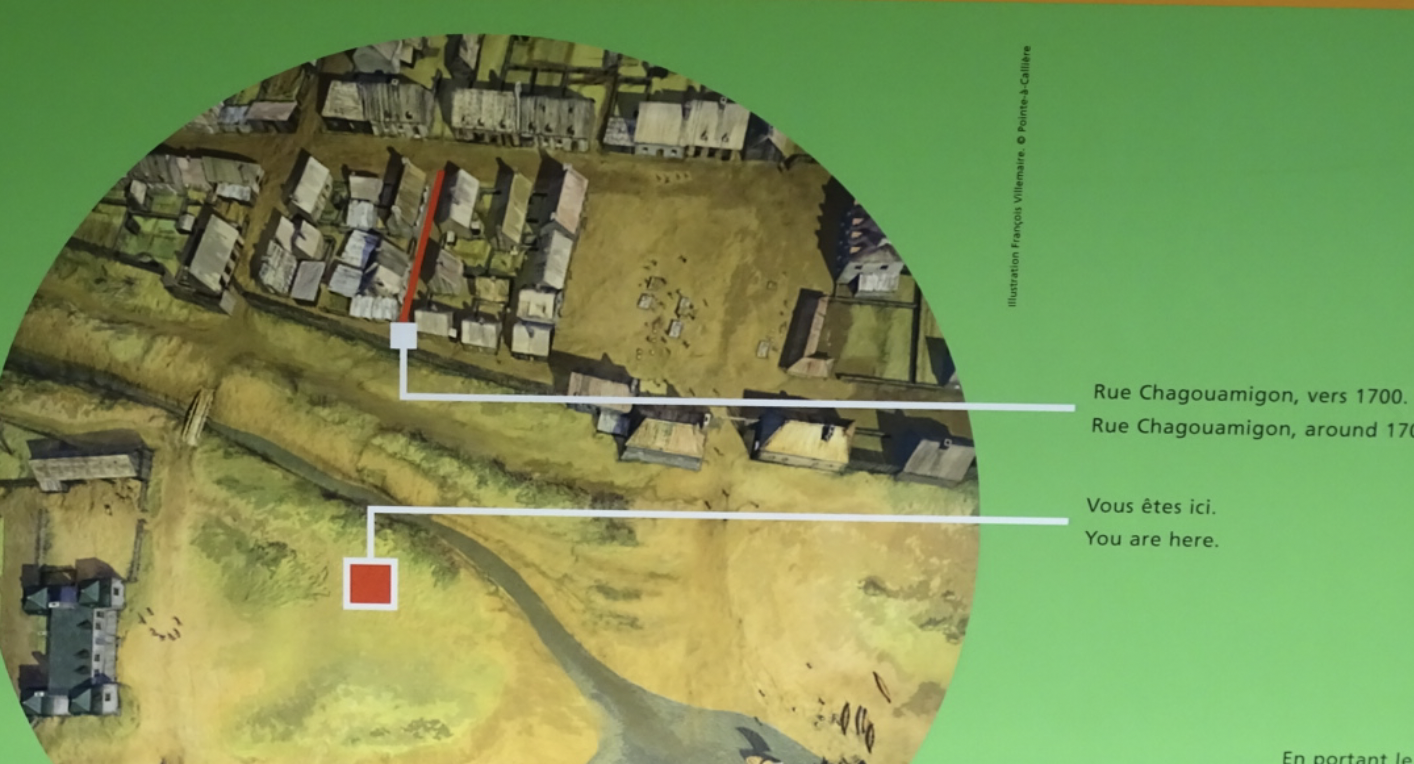

ASHLAND, Wis., Dec. 31. – Judge Bell, known far and wide as “King of the Apostle Islands,” died yesterday. For nearly half a century he governed what was practically a little monarchy in the wilderness. He was 83 years old, and was the oldest living settler on the historic spot where Marquette founded his mission, two hundred years ago.

KING OF THE ISLANDS.

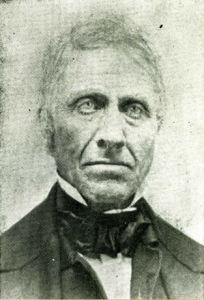

Judge Bell,

“King of the Apostle Islands,”

Has Given Up His Crown.

The Oldest Living Pioneer

of the Historic Spot

Dies in Apparent Poverty,

Special to the Globe.

ASHLAND, Wis., – “The king of the Apostle islands” is dead. He passed away at an early hour this morning at La Pointe, on Madeline, the largest of the group, where he has lived for forty-four years, the oldest living pioneer of the historic spot where Pere Marquette founded his little Indian mission 200 years ago. Judge Bell was a character in the early history of the Lake Superior region, known far and wide as the “king” of the country known as La Pointe, which was organized in 1846 by Judge Bell. The area of the country was as large as many states of the Union, its borders including nearly all of Wisconsin north of the Chippewa river, the Apostle islands and to an almost

ENDLESS DISTANCE WEST.

Wisconsin Historical Society’s copy of Lyman Warren’s 1834 “Map of La Pointe” from the American Fur Company Papers at New York Historical Society.

The population of whites consisted only of a small handful of French voyagers, traders and trappers, most of whom rendezvous at La Pointe. The country was hardly known by the state, and Bell’s county was practically a young monarchy. He bossed everything and everybody, but in such a way that every Indian and every white was his friend and follower. Judge Bell came here in 1832, from Canada, in the employ of the American Fur company, which at that time was a power here. He had rarely left the island, except in years gone by to make occasional pilgrimages through the settlements. During his eventful life he held every office in the county, and for many years, served as county judge. He was a man of great native ability, possessed of a courage that controlled the rough element which surrounded him in the early days when there was no law except his will. He was honest, fearless,

A NATURAL-BORN RULER

of men, and through his efforts the poor and needy were cared for, and in no instance did he fail to befriend them. For this reason among those who survive him, and who lived in the good old pioneer days, all were his firm friends. His power departed only when the advance guard of civilization reached the great inland sea, through the medium of the iron horse, and opened a new era in the history of the new Wisconsin. For many years he has been old and feeble and has suffered for the comforts of life, having become a charge upon the town. He squandered thousands for the people and died poor but not friendless. He was eighty-three years of age.

ANOTHER PIONEER GONE

DEATH OF “SQUIRE” BELL, “THE KING OF LAPOINTE.”

Sketch of the Life of the Oldest Settler in the Lake Superior Region.

He comes to La Pointe With John Jacob Astor for the American Fur Co.

Judge John W. Bell died Friday morning at seven o’clock at his home at La Pointe, on Madeline Island, aged eighty-four years.

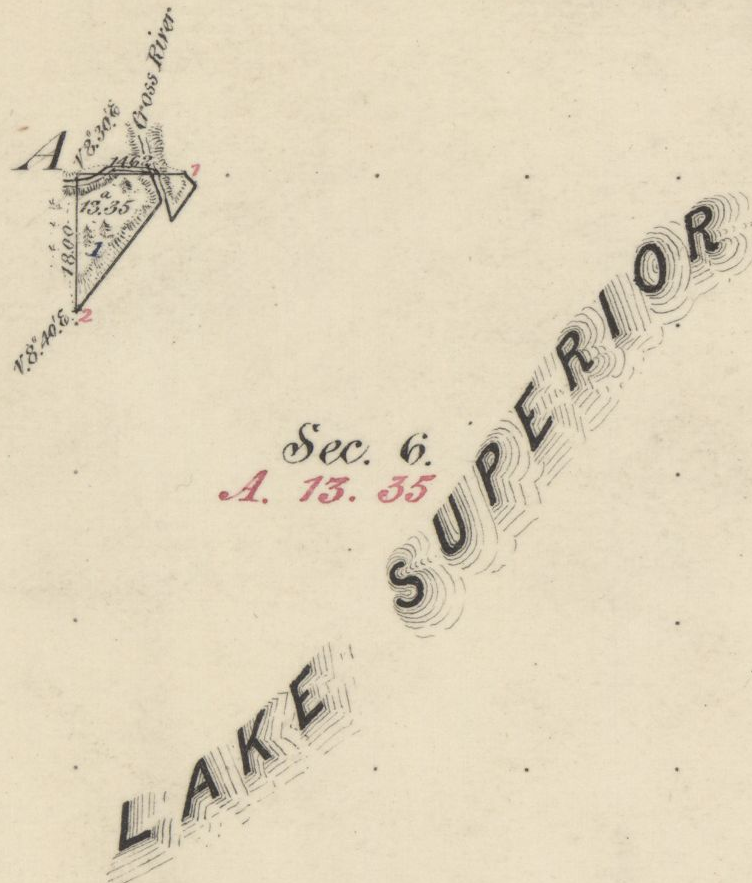

1847 PLSS survey map detailing the mouth of Iron River at what is now Silver City, Michigan along the east entrance to the Porcupine Mountains.

John W. Bell was born in New York City on May 3, 1803, and was consequently eighty-four years and seven months old. He learnt the trade of a cooper, and in this capacity in the year 1835, he came to the Lake superior country for the United States Fur company. He first settled at the mouth of Iron river, in Michigan, about twenty miles west of Ontonagon. Here, at that time, was one of the principal trading and fishing posts of the American Fur company, La Pointe being its headquarters. Remaining at Iron river for a few years, he came to La Pointe about 1840, where he continued to reside till the time of his death.

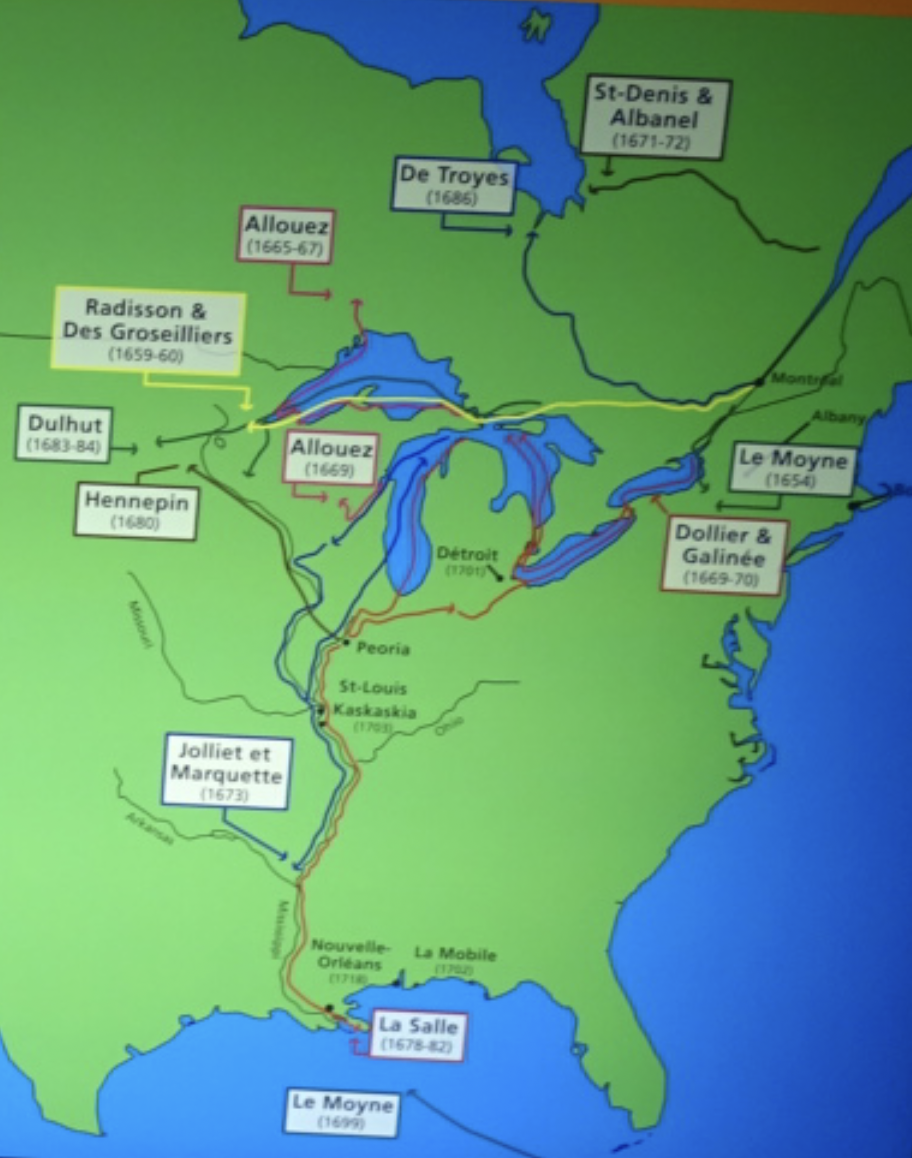

1845 United States map by John Dower, with the northernmost area of Wisconsin Territory that became La Pointe County.

At the time he came upon this lake its shores were an unbroken wilderness. At the Sault was a United States fort, but from the foot of Lake Superior to the Pacific ocean, no white settlement existed. The American and Northwest Fur companies were lords of this vast empire, and their trading posts and a few mission stations connected with them, held control. A small detachment of United States soldiers formed the distant outposts of Ft. Snelling. The state of Wisconsin had not been organized. No municipal government existed upon this lake. It was many years before Wisconsin was organized.

1845 United States map by J. Calvin Smith, with the original 1845 boundaries of La Pointe County added in red outline.

“beginning at the mouth of Muddy Island river [on the Mississippi River], thence running in a direct line to Yellow Lake, and from thence to Lake Courterille, so to intersect the eastern boundary line at that place, of the county of St Croix, thence to the nearest point on the west fork of Montreal river, thence down said river to Lake Superior.”

Finally the county of La Pointe was formed, embracing all Wisconsin bordering upon the lake and extending to town forty north. “Squire Bell,” as he was always called, became one of the county as well as town officers of the town and county of La Pointe, and for more than thirty years continued to hold office, being at different times chairman of supervisors, register of deeds, justice of the peace, clerk of the circuit court and county judge. This last office he held for many years.

He was a man of genial nature and robust frame. About four years ago, while in Ashland he fell and fractured his thigh, and was never able to walk again. His sufferings from this accident were great and his pleasant face was never seen again in Ashland. He enjoyed the esteem and friendship of his neighbors, so far as is known without exception. He was clear headed and of commanding appearance. His influence among the Indians and the French who for many years were the only inhabitants in the country was very great, and continued to the last. For years his dictum was the last resort for the settlement of the quarrels in this primitive community, and it seems to have been just and satisfactory. He was often called “The King of La Pointe,” and for years no one disputed his supremacy.

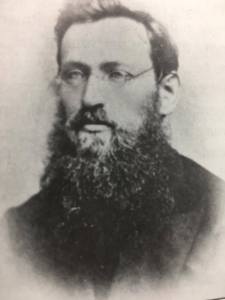

Edwin Ellis, M.D.

Dr. Edwin Ellis, of this city, said in speaking of the dead old pioneer:

“Thus one by one the early settlers are passing away, and ere long an entirely new generation will occupy the old haunts. He will rest upon the beautiful isle overlooking Chequamegon bay, where the landscape has been familiar to him for more than a generation. We a little longer linger on the shores of time, waiting the summons to cross the river. While we consign the body of an old friend to the earth we will in all heartfelt sorrow say: ‘Requiescat in Pace.'”

The Lake Superior Monarch

Judge Bell, the ‘king of the Apostle islands,’ who died the other day on Madeline Island at the age of eighty-three, was a conspicuous character in the early history of the Lake Superior region. He was the “king” of the county known as La Pointe, which was organized in 1846 by himself. The county was as large as many states of the Union, its borders including nearly all of Wisconsin north of the Chippewa river, the Apostle islands, and to an almost endless distance west. The white population consisted of a handful of French voyagers, traders and trappers, most of whom made their rendezvous at La Pointe. The country was hardly known by the state, and Bell’s realm was practically a little monarchy. He “bossed” everything and everybody, but in such a way that every Indian and every white was his friend and follower. Judge Bell rarely left the island except to make occasional pilgrimages through the settlements. During his eventful life he held every office in the county, and of late years had served as county judge. He was a man of great native ability, and was possessed of a courage that controlled the rough element that surrounded him in the early days when there was no law except his will. He was an honest, fearless, natural-born ruler of men. Through his efforts the poor and needy were cared for. His power departed only when the advanced guard of civilization reached the great inland sea. For many years he had been feeble, and of late had become a charge upon the town. He spent thousands upon the people.

To be continued in Fooled the Austrian Brothers…

Chequamegon History Event: Trails & Towns Before Washburn

March 31, 2025

Join Amorin Mello at the Bayfield Heritage Association for a fun afternoon exploring maps and stories about Ancient Trails and Ghost Towns before the City of Washburn was founded in 1883.

2pm Sunday April 27, 2025 at the Bayfield Heritage Association.

Sponsored by the Apostle Islands Historic Preservation Conservancy.

Judge Bell Incidents: King of the Apostle Islands

January 30, 2025

Collected & edited by Amorin Mello

This post is the first of a series featuring The Ashland News items about La Pointe’s infamous Judge John William Bell, written mainly by his son-in-law George Francis Thomas née Gilbert Fayette Thomas a.k.a G.F.T.

Wednesday, September 30, 1885, page 2.

Wednesday, September 30, 1885, page 2.

ON HISTORICAL GROUND.

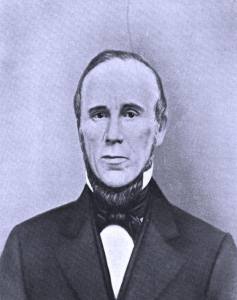

James Chapman

~ Madeline Island Museum

Judge Joseph McCloud

~ Madeline Island Museum

Saturday last, says The Bayfield Press, the editor had the pleasure of visiting Judge John W. Bell at his home at La Pointe, accompanied by Major Wing, James Chapman and Judge Joseph McCloud. The judge, now in his 81st year, still retains much of that indomitable energy that made him for many years a veritable king of the Apostle Islands. Owing, however, to a fractured limb and an irritating ulcer on his foot he is mostly confined to his chair. His recollection of the early history of this country is vivid, while his fund of anecdotes of his early associates is apparently inexhaustible and renders a visit to this remarkable pioneer at once full of pleasure and instruction. The part played by Judge Bell in the early history of this country is one well worthy of preservation and in the hands of competent parties could be made not the least among the many historical sketches of the pioneers of the great northwest. The judge’s present home is a large, roomy house, located in the center of a handsome meadow whose sloping banks are kissed by the waters of the lake he loves so well. Here, surrounded by children and grand-children, cut off from the noise and bustle of the outside world, his sands of life are peacefully passing away.

Leaving La Pointe our little party next visited the site of the Apostle Islands Improvement company’s new summer resort and found it all the most vivid fancy could have painted. Here, also, we met Peter Robedeaux, the oldest surviving voyager of the Hudson Bay Fur Co. Mr. Robedeaux is now in his 89th year, and is as spry as any man not yet turned fifty. He was born near Montreal in 1796, and when only fourteen years of age entered the employ of the Hudson Bay Fur Co., and visited the then far distant waters of the Columbia river, in Washington Territory. He remained in the employ of this company for twenty-five years and then entered the employ of the American Fur company, with headquarters at La Pointe. For fifty years this man has resided on Madeline Island, and the streams tributary to the great lake not visited by him can be numbered by the fingers on one’s hand. His life until the past few years has been one crowded with exciting incidents, many of which would furnish ample material for the ground-work of a novel after the Leather Stocking series style.

Wednesday, June 30, 1886, page 2.

Wednesday, June 30, 1886, page 2.

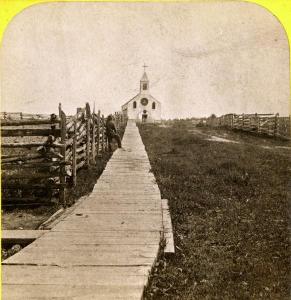

GOLDEN WEDDING.

About thirty of the old settlers of Ashland and Bayfield went over to La Pointe on Saturday to celebrate the golden wedding anniversary of Judge John W. Bell and wife, who were married in the old church at La Pointe June 26th, 1836, fifty years ago. The party took baskets containing their lunch with them, the old couple having no knowledge of the intended visit. After congratulations had been extended the table was spread, and during the meal many reminiscences of olden times were called up.

Judge Bell is in his eighty-third year, and is becoming quite feeble. Mrs. Bell is perhaps ten or twelve years younger. Judge Bell came to La Pointe in 1834, and has lived there constantly ever since. La Pointe used to be the county seat of Ashland county, and prior to the year 1872 Judge Bell performed the duties of every office of the county. In fact he was virtually king of the island.

The visitors took with them some small golden tokens of regard for the aged couple, the coins left with them aggregating between $75 and $100.

Wednesday, July 20, 1887, page 6.

Wednesday, July 20, 1887, page 6.

REMINISCENCES OF OLD LA POINTE

(Written for The Ashland News)

Visitors to this quiet and delapidated old town on Madeline Island, Lake Superior, about whom early history and traditions so much has been published, are usually surprised when told that less than forty years have passed since there flourished at this point a city of about 2,500 people. Now not more than thirty families live upon the entire island. Thirty-five years ago neither Bayfield, Ashland nor Washburn was thought of, and La Pointe was the metropolis of Northern Wisconsin.

Since interesting himself in the island the writer has often been asked: Why, if there were so many inhabitants there as late as forty years ago, are there so few now? In reply a great number of reasons present themselves, chief among which are natural circumstances, but in the writer’s mind the imperfect land titles clouding old La Pointe for the last thirty years have tended materially to hastening its downfall.

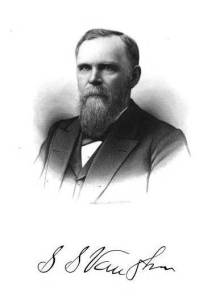

Captain John Daniel Angus

~ Madeline Island Museum

Of the historic data of La Pointe, of which the writer has almost an unlimited supply, much that seems romance is actual fact, and the witnesses of occurrences running back over fifty years are still here upon the island and can be depended upon for the truthfulness of their reminiscences. There are no less than five very old men yet living here who have made their homes upon the island for over fifty years. Judge John W. Bell, or “Squire,” as he is familiarly called, has lived here since the year 1835, coming from the “Soo,” on the brig, John Jacob Astor, in company with another old pioneer of the place known as Capt. John Angus. Mr. Bell contracted with the American Fur Co., and Capt. Angus sailed the “Big Sea” over. Mr. Bell is now eighty three years of age, and is crippled from the effects of a fall received while attending court in Ashland, in Jan. 1884. He is a man of iron constitution and might have lived – and may yet for all we know – to become a centenarian. The hardships of pioneer life endured by the old Judge would have killed an ordinary man long ago. He is a cripple and an invalid, but he has never missed a meal of victuals nor does he show any sign of weakening of his wonderful mind. He delights to relate reminiscences of early days, and will talk for hours to those who prove congenial. Once in his career, Mr. Bell had in his employ the famous “Wilson, the Hermit,” whose romantic history is one of the interesting features sought after by tourists when they visit the islands.

~ History of Northern Wisconsin, by the Western Historical Co., 1881.

Once Mr. Bell started an opposition fur company having for his field of operations that portion of Northern Wisconsin and Michigan now included within the limits of the great Gogebic and Penokee iron ranges, and had in his employ several hundred trappers and carriers. Later Mr. Bell became a prominent explorer, joining numerous parties in the search for gold, silver and copper; iron being considered too inferior a metal for the attention of the popular mind in those days.

Almost with his advent on the island Mr. Bell became a leader in the local political field, during his residence of fifty-two years holding almost continually some one of the various offices within the gift the people. He was also employed at various times by the United States government in connection with Indian affairs, he having a great influence with the natives.

Ramsay Crooks

~ Madeline Island Museum

The American Fur Co., with Ramsay Crooks at its head gave life and sustenance to La Pointe a half century ago, and for several years later, but when a private association composed of Borup, Oakes and others purchased the rights and effects of the American Fur Co., trade at La Pointe began to fall away. The halcyon days were over. The wild animals were getting scarce, and the great west was inducing people to stray. The new fur company eventually moved to St. Paul, where even now their descendants can be found.

Julius Austrian

~ Madeline Island Museum

Prior to the final extinction of the fur trade at La Pointe and in the early days of steamboating on the great lakes, the members of the well-known firm of Leopold & Austrian settled here, and soon gathered about them a number of their relatives, forming quite a Jewish colony. They all became more or less interested in real estate, Julius and Joseph Austrian entering from the government at $1.25 per acre all the lands upon which the village was situated, some 500 acres.

The original patent issued by the government, of which a copy exists in the office of the register of deeds in Ashland, is a literary curiosity, as are also many other title papers issued in early days. Indeed if any one will examine the records and make a correct abstract or title history of old La Pointe, the writer will make such person a present of one of the finest corner lots on the island. Such a thing can not be done simply from the records. A large portion of the original deeds for village lots were simply worthless, but the people in those days never examined into the details, taking every man to be honest, hence errors and wrongs were not found out.

Now the lots are not worth the taxes and interest against them, and the original purchaser will never care whether his title was good or otherwise. The county of Ashland bought almost the whole town site for taxes many years ago and has had an expensive load to carry until the writer at last purchased the tax titles of the village, which includes many of the old buildings. The writer has now shouldered the load, and proposes to preserve the old relics that tourists may continue to visit the island and see a town of “Ye olden times.”

Originally the intention was to form a syndicate to purchase the old town. An association of prominent citizens of Ashland and Bayfield, at one time came very near securing it, and the writer still has hopes of such an association some day controlling the historical spot. The scheme, however, has met with considerable opposition from a few who desire no changes to be made in the administration of affairs on the island. The principal opponent is Julius Austrian, of St. Paul, who still owns one-sixth part of La Pointe, and is expecting to get back another portion of lots, which have been sold for taxes and deeded by the county ever since 1874. He would like no doubt, to make Ashland county stand the taxes on the score of illegality. As a mark of affection for the place, he has lately removed the old warehouse which has stood so many years a prominent landmark in La Pointe’s most beautiful harbor. Tourists from every part of the world who have visited the old town will join in regretting the loss and despise the action.

G. F. T.

To be continued in King No More…

Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Coda

June 1, 2024

My last post ended up containing several musings on the nature of primary-source research and how to acknowledge mistakes and deal with uncertainty in the historical record. This was in anticipation of having to write this post. It’s a post I’ve been putting off for years.

Amorin forced the issue with his important work on the speeches at the 1842 Treaty negotiations. While working on it, he sent me a message that read something like, “Hey, the article quotes Chief Buffalo and describes him in a blue military coat with epaulets. Is the world ready for that picture that Smithsonian guy sent us years ago?”

This was the image in question:

Henry Inman, Big Buffalo (Chippewa), 1832-1833, oil on canvas, frame: 39 in. × 34 in. × 2 1/4 in. (99.1 × 86.4 × 5.7 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Gerald and Kathleen Peters, 2019.12.2

We first learned of this image from a Chequamegon History comment by Patrick Jackson of the Smithsonian asking what we knew about the image and whether or not it was Chief Buffalo from La Pointe.

We had never seen it before.

This was our correspondence with Mr. Jackson at the time:

July 17, 2019

Hello, my name is Patrick, and I am an intern at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I’m working on researching a recent acquisition: a painting which came to us identified as a Henry Inman portrait of “Big Buffalo Ke-Che-Wais-Ke, The Great Renewer (1759-1855) (Chippewa).” We have run into some confusion about the identification of the portrait, as it came to us identified as stated above, yet at Harvard Peabody Museum, who was previously the owner of the portrait, it was listed as an unidentified sitter. Seeing as you’ve written a few posts about the identification of images of the three different Chief Buffalos, I thought you might be able to give some insight into perhaps who is or isn’t in the portrait we have. Thank you for your time.

July 17, 2019

Hello,

I would be happy to comment. Can you send a photo to this email?

I am pretty sure Inman painted a copy of Charles Bird King’s portrait of Pee-che-kir.

Doe it resemble that portrait? Pee-che-kir (Bizhiki) means Buffalo in Ojibwe (Chippewa). From my research, I am fairly certain that King’s portrait is not of Kechewaiske, but of another chief named Buffalo who lived in the same era.

Leon Filipczak

July 17, 2019

Dear Leon,

I have attached our portrait—it’s not the best scan, but hopefully there’s enough detail for you to work with. I’ve compared it with the Peechikir in McKenney & Hall, as well as to the Chief Buffalo painted ambrotype and the James Otto Lewis portrait of Pe-schick-ee. The ambrotype has a close resemblance, as does the Peecheckir, though if that is what Charles Bird King painted I have doubts that Inman would make such drastic changes in clothing and pose.

The identification as Big Buffalo/Ke-Che-Wais-Ke/The Great Renewer, as far as I understand, refers to the La Pointe Bizhiki/Buffalo rather than the St. Croix or Leech Lake Buffalos, though of course that is a questionable identification considering Kechewaiske did not (I think) visit Washington until after Inman’s death in January of 1846. McKenney, however, did visit the Ojibwe/Chippewa for the negotiations for the Treaty of Fond du Lac in 1825/1826, and could feasibly have met multiple Chief Buffalos. Perhaps a local artist there would be responsible for the original? Another possibility is, since the identification was not made at the Peabody, who had the portrait since the 1880s, is that it has been misidentified entirely and is unrelated to any of the Ojibwe/Chippewa chiefs. Though this, to me, would seem unlikely considering the strong resemblance of the figure in our portrait to the Peechikir portrait and Chief Buffalo ambrotype.

Thank you again for the help.

Sincerely,

Patrick

July 22, 2019

Hello Patrick,

This is a head-scratcher. Your analysis is largely what I would come up with. My first thought when I saw it was, “Who identified it as someone named Buffalo? When? and using what evidence?” Whoever associated the image with the text “Ke-Che-Wais-Ke, The Great Renewer (1759-1855)” did so decades after the painting could be assumed to be created. However, if the tag “Big Buffalo” can be attached to this image in the era it was created, then we may be onto something. This is what I know:

1) During his time as Superintendent of Indian Affairs (late 1820s), Thomas McKenney amassed a large collection of portraits of Indian chiefs for what he called the “Indian Gallery” in the War Department. He sought the portraits out wherever and whenever he could. When chiefs would come to Washington, he would have Charles Bird King do the work, but he also received portraits from the interior via artists like James Otto Lewis.

2) In 1824, Bizhiki (Buffalo) from the St. Croix River (not Great Buffalo from La Pointe), visited Washington and was painted by King. This painting is presumed to have been destroyed in the Smithsonian fire that took out most of the Indian Gallery.

3) In 1825 at Prairie du Chien and in 1826 at Fond du Lac (where McKenney was present) James Otto Lewis painted several Ojibwe chiefs, and these paintings also ended up in the Indian Gallery. Both chief Buffalos were present at these treaties.

4) A team of artists copied each others’ work from these originals. King, for example remade several of Lewis’ portraits to make the faces less grotesque. Inman copied several Indian Gallery portraits (mostly King’s) to be sent to other institutions. These are the ones that survived the Smithsonian fire.

5) In the late 1830s, 10+ years after most of the portraits were painted, Lewis and McKenney sold competing lithograph collections to the American public. McKenney’s images were taken from the Indian Gallery. Lewis’ were from his works (some of which were in the Indian Gallery, often redone by King). While the images were printed with descriptions, the accuracy of the descriptions leaves something to be desired. A chief named Bizhiki appears in both Lewis and McKenney-Hall. In both, the chiefs are dressed in white and faced looking left, but their faces look nothing alike. One is very “Lewis-grotesque.” and the other is not at all. There are Lewis-based lithographs in both competing works, and they are usually easy to spot.

6) Not every image from the Indian Gallery made it into the published lithographic collections. Brian Finstad, a historian of the upper-St. Croix country, has shown me an image of Gaa-bimabi (Kappamappa, Gobamobi), a close friend/relative of the La Pointe Chief Buffalo, and upstream neighbor of the St. Croix Buffalo. This image is held by Harvard and strongly resembles the one you sent me in style. I suspect it is an Inman, based on a Lewis (possibly with a burned-up King copy somewhere in between).

7) “Big Buffalo” would seemingly indicate Buffalo from La Pointe. The word gichi is frequently translated as both “great” and “big” (i.e. big in size or big in power). Buffalo from La Pointe was both. However, the man in the painting you sent is considerably skinnier and younger-looking than I would expect him to appear c.1826.

My sense is that unless accompanying documentation can be found, there is no way to 100% ID these pictures. I am also starting to worry that McKenney and the Indian Gallery artists, themselves began to confuse the two chief Buffalos, and that the three originals (two showing St. Croix Buffalo, and one La Pointe Buffalo) burned. Therefore, what we are left with are copies that at best we are unable to positively identify, and at worst are actually composites of elements of portraits of two different men. The fact that King’s head study of Pee-chi-kir is out there makes me wonder if he put the face from his original (1824 portrait of St. Croix Buffalo?) onto the clothing from Lewis’ portrait of Pe-shick-ee when it was prepared for the lithograph publication.

A few weeks later, Patrick sent a follow-up message that he had tracked down a second version and confirmed that Inman’s portrait was indeed a copy of a Charles Bird King portrait, based on a James Otto Lewis original. It included some critical details.

Portrait of Big Buffalo, A Chippewa, 1827 Charles Bird King (1785-1862), signed, dated and inscribed ‘Odeg Buffalo/Copy by C King from a drawing/by Lewis/Washington 1826’ (on the reverse) oil on panel 17 1⁄2 X 13 3⁄4 in. (44.5 x 34.9 cm.) Last sold by Christie’s Auction House for $478,800 on 26 May 2022

The date of 1826 makes it very likely that Lewis’ original was painted at the Treaty of Fond du Lac. Chief Buffalo of La Pointe would have been in his 60s, which appears consistent with the image of Big Buffalo. Big Buffalo also does not appear as thin in King’s intermediate version as he does in Inman’s copy, lessening the concerns that the image does not match written descriptions of the chief.

Another clue is that it appears Lewis used the word Odeg to disambiguate Big Buffalo from the two other chiefs named Buffalo present at Fond du Lac in 1826. This may be the Ojibwe word Andeg (“crow”). Although I have not seen any other source that calls the La Pointe chief Andeg, it was a significant name in his family. He had multiple close relatives with Andeg in their names, which may have all stemmed from the name of Buffalo’s grandfather Andeg-wiiyaas (Crow’s Meat). As hereditary chief of the Andeg-wiiyaas band, it’s not unreasonable to think the name would stay associated with Buffalo and be used to distinguish him from the other Buffalos. However, this is speculative.

So, there we were. After the whole convoluted Chief Buffalo Picture Search, did we finally have an image we could say without a doubt was Chief Buffalo of La Pointe? No. However, we did have one we could say was “likely” or even “probably” him. I considered posting at the time, but a few things held me back.

In the earliest years of Chequamegon History, 2013 and 2014, many of the posts involved speculation about images and me trying to nitpick or disprove obvious research mistakes of others. Back then, I didn’t think anyone was reading and that the site would only appeal to academic types. Later on, however, I realized that a lot of the traffic to the site came from people looking for images, who weren’t necessarily reading all the caveats and disclaimers. This meant we were potentially contributing to the issue of false information on the internet rather than helping clear it up. So by 2019, I had switched my focus to archiving documents through the Chequamegon History Source Archive, or writing more overtly subjective and political posts.

So, the Smithsonian image of Big Buffalo went on the back burner, waiting to see if more information would materialize to confirm the identity of the man one way or the other. None did, and then in 2020 something happened that gave the whole world a collective amnesia that made those years hard to remember. When Amorin asked about using the image for his 1842 post, my first thought was “Yeah, you should, but we should probably give it its own post too.” My second thought was, “Holy crap! It’s been five years!”

Anyway, here is Chequamegon History’s statement on the identity of the man in Henry Inman’s 1832-33 portrait of Big Buffalo (Chippewa).

Likely Chief Buffalo of La Pointe: We are not 100% certain, but we are more certain than we have been about any other image featured in the Chief Buffalo Picture Search. This is a copy of a copy of a missing original by James Otto Lewis. Lewis was a self-taught artist who struggled with realistic facial features. Charles Bird King and Henry Inman, who made the first and second copies, respectively, had more talent for realism. However, they did not travel to Lake Superior themselves and were working from Lewis’ original. Therefore, the appearance of Big Buffalo may accurately show his clothing, but is probably less accurate in showing his actual physical appearance.

And while we’re on the subject of correcting misinformation related to images, I need to set the record straight on another one and offer my apologies to a certain Benjamin Green Armstrong. I promise, it relates indirectly to the “Big Buffalo” painting.

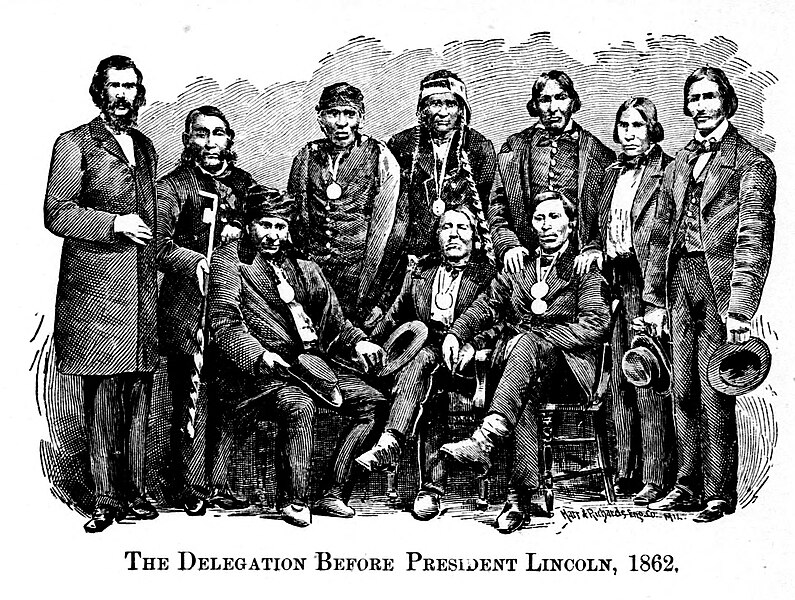

An engraving of the image in question appears in Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians.

Ah-moose (Little Bee) from Lac Flambeau Reservation, Kish-ke-taw-ug (Cut Ear) from Bad River Reservation, Ba-quas (He Sews) from Lac Courte O’Rielles Reservation, Ah-do-ga-zik (Last Day) from Bad River Reservation, O-be-quot (Firm) from Fond du Lac Reservation, Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation, Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell) from La Pointe Reservation, Na-gon-ab (He Sits Ahead) from Fond du Lac Reservation, and O-ma-shin-a-way (Messenger) from Bad River Reservation.

In this post, we contested these identifications on the grounds that Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Little Buffalo) from La Pointe Reservation died in 1860 and therefore could not have been part of the delegation to President Lincoln. In the comments on that post, readers from Michigan suggested that we had several other identities wrong, and that this was actually a group of chiefs from the Keweenaw region. We commented that we felt most of Armstrong’s identifications were correct, but that the picture was probably taken in 1856 in St. Paul.

Since then, a document has appeared that confirms Armstrong was right all along.

[Antoine Buffalo, Naagaanab, and six other chiefs to W.P. Dole, 6 March 1863

National Archives M234-393 slide 14

Transcribed by L. Filipczak 12 April 2024]

To Our Father,

Hon W P. Dole

Commissioner of Indian Affairs–

We the undersigned chiefs of the chippewas of Lake Superior, now present in Washington, do respectfully request that you will pay into the hands of our Agent L. E. Webb, the sum of Fifteen Hundred Dollars from any moneys found due us under the head of “Arrearages in Annuity” the said money to be expended in the purchase of useful articles to be taken by us to our people at home.

Antoine Buffalo His X Mark | A daw we ge zhig His X Mark

Naw gaw nab His X Mark | Obe quad His X Mark

Me zhe na way His X Mark | Aw ke wen zee His X Mark

Kish ke ta wag His X Mark | Aw monse His X Mark

I certify that I Interpreted the above to the chiefs and that the same was fully understood by them

Joseph Gurnoe

U.S. Interpreter

Witnessed the above Signed } BG Armstrong

Washington DC }

March 6th 1863 }

There were eight Lake Superior chiefs, an interpreter, and a witness in Washington that spring, for a total of ten people. There are ten people in the photograph. Chequamegon History is confident that this document confirms they are the exact ten identified by Benjamin Armstrong.

The Lac Courte Oreilles chief Ba-quas is the same person as Akiwenzii. It was not unusual for an Ojibwe chief to have more than one name. Chief Buffalo, Gaa-bimaabi, Zhingob the Younger, and Hole-in-the-Day the Younger are among the many examples.

The name “Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation” seems to be absent from the letter, but he is there too. Let’s look at the signature of the interpreter, Joseph Gurnoe.

Gurnoe’s beautiful looping handwriting will be familiar to anyone who has studied the famous 1864 bilingual petition. We see this same handwriting in an 1879 census of Red Cliff. In this document, Gurnoe records his own Ojibwe name as Shingwākons, The young Pine tree.

So the man standing on the far right is Gurnoe. This can be confirmed by looking at other known photos of him.

Finally, it confirms that the chief seated on the bottom left is not Jechiikwii’o (Little Buffalo), but rather his son Antoine, who inherited the chieftainship of the Buffalo Band after the death of his father two years earlier. Known to history as Chief Antoine Buffalo, in his lifetime he was often called Antoine Tchetchigwaio (or variants thereof), using his father’s name as a surname rather than his grandfather’s.

So, now we need to address the elephant in the room that unites the Henry Inman portrait of Big Buffalo with the photograph of the 1862-63 Delegation to Washington:

Wisconsin Historical Society

This is the “ambrotype” referenced by Patrick Jackson above. It’s the image most associated with Chief Buffalo of La Pointe. It’s also one for which we have the least amount of background information. We have not been able to determine who the original photographer/painter was or when the image was created.

The resemblance to the portrait of “Big Buffalo” is undeniable.

However, if it is connected to the 1862-63 image of Chief Antoine Buffalo, it would support Hamilton Nelson Ross’s assertions on the Wisconsin Historical Society copy.

Clearly, multiple generations of the Buffalo family wore military jackets.

Inconclusive: uncertainty is no fun, but at this point Chequamegon History cannot determine which Chief Buffalo is in the ambrotype. However, the new evidence points more toward the grandfather (Great Buffalo) and grandson (Antoine) than it does to the son (Little Buffalo).

We will keep looking.