Penokee Survey Incidents: Number IV

February 22, 2015

By Amorin Mello

Increase Allen Lapham surveyed the Penokee Iron Range in September of 1858 for the Wisconsin & Lake Superior Mining and Smelting Company. Years later, Lapham’s experience was published as “Mountain of Iron Ore: The buried wealth of Northern Wisconsin“ in the Milwaukee Evening Wisconsin newspaper on February 21, 1887. (Image courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Geography Department)

~ 1978 Marsden Report for US Steel.

~ Railroad History, Issues 54-58, pg. 26

The Penoka Iron Range consists, as is well known, of a sharp ridge, some fifteen miles in length, by from one to one and one half in breadth, with a mean elevation of 700 feet above Lake Superior, from which is a distance about twenty-two miles, as the crow flies, its general trend being nearly east and west, it is densely covered with timber consisting of sugar maple, (of which nearly every tree is birdseye or curly) elm, red cedar, black, or yellow birch, some of which are of an enormous girth, among which are intermixed a few white pine and balsams, for it is traversed from north to south at three different points, by running streams, upon each of which the company had a station, the western being known in the vernacular of the company, as Palmer’s, (now Penoka); the center, as Lockwood’s, in honor of John Lockwood, who was at the time a prominent member of the Company, and upon its executive board; and the eastern, as Sidebotham’s, or “The Gorge.” These were the principal stations or centers, where supplies and men were always kept, and as which, as before stated, more or less work had been done the previous year. Penoka, as which the most work had been done, being considered by far the most valuable. This post was, at the time of my first visit, by charge of S.R. Marston, of whom mention was made in my last, and two young boys from Portsmouth, N.H., who had come west on exhibition, I should say, from the way they acted. They soon left, however, too many mosquitoes for them. “Lockwood’s,” as previously stated, was garrisoned by one man, whose name I have forgotten, and although a great amount of work had been done here as yet, it was nevertheless considered a very valuable claim, on account of the feasibility with which it could be reached by the rail Mr. Herbert had in contemplation to build from Ironton, and which would, in passing along the north side of the Range, come in close proximity to this station; besides, it had the additional advantages of a fine water power. At the east end were two half-breeds employed by the company, and George Chase, a young man from Derby, Vermont, a nephew of ex-Mayor Horace, and Dr. Enoch Chase, of Milwaukee, an employee of Stuntz, who, with James Stephenson, was awaiting the return of Gen. Cutler with reinforcements, in order to continue the survey. Chase subsequently made a claim which he was successful in securing – selling it finally to the Mr. Cogswell, of Milwaukee.

It is also proper to state in addition to what has been already mentioned, that at, or about this time, a road was opened by Mr. Herbert’s order, from the Hay Marsh, six miles out from Ironton, to which point one had been previously opened, to the Range, which it struck about midway between Sidebotham’s and Lockwood’s Stations, over which, I suppose, the 50,000 tons as previously mentioned, was to find its way to Ironton, (in a horn). For this work, however, the Company refused to pay, as they had not authorized it; neither had Mr. Herbert, at that time, any authority to contract for it, except at his own risk; his appointment as agent having already been revoked; although his accounts had not, as yet, been fully settled. This work, which was without doubt, intended to commit the company still further in favor of Ironton as an outlet for the iron, was done by Samuel Champner, a then resident of Ashland and who if living is probably that much out of pocket today. No use was ever made of this road by the Company, not one of their employees, to my knowledge, ever passing over it.

This description will, I think, give your readers a very good understanding of the condition as well as the true inwardness of the affairs of the Wisconsin & Lake Superior Mining and Smelting Co., in the month of June, 1857.

At length, after remaining on the Range nearly three weeks, awaiting, Micawber like, for something to turn up, a change came with the arrival of Gen. Cutler from Milwaukee with the expected reinforcements. Mr. Herbert at once left the Range, went to Milwaukee and settled up with the Company, after which, to use a scriptural expression, “he walked no more with us.”

“A special defense in contract law to allow a person to avoid having to respect a contract that she or he signed because of certain reasons such as a mistake as to the kind of contract.”

~ Duhaime.org

Wheelock, Smith, and McClellan were at once placed upon claims – McClellan in the interest of John Cummings, (whose name by an oversight was also omitted from the list of stockholders, given in my first paper), and Wheelock and Smith for the Company generally. Subsequently, A.S. Stacy, of Canada, was also employed to hold a claim. How well he performed this duty, will be seen further on. This done, the improvements necessary to be made in order to entitle us to the benefits of the preemption law were at once commenced. These improvements consisted of log cabins, principally, of which some twenty in all were erected upon the different claims. These cabins would have been a study for Michel Angelo, or Sir Christopher Wren. They had more angles than the Forty-seventh Problem of Euclid, with an average inclination of fifteen degrees to the Ecliptic. O, but they were “fearfully and wonderfully made,” were these cabins. Their construction embodied all the principle points of architecture in the Ancient as well as Modern–Milesian-Greek, mixed with the “hoop skirt” and Heathen Chimee. Probably ten dollars a month would have been considered a high rent for any of them. No such cabins as those were in exhibition at the Centennial, no sir. Rome was not built in a day, but most of these cabins were. I built four myself near the Gorge, in a day, with the assistance of two halfbreeds, but was not able to find them a week afterwards. This is not only a mystery but a conundrum. I think some traveling showman must have stolen them; but although they were non est we could swear that we had built them, and did.

Springdale townsite plan at Sidebotham’s station by The Gorge of Tyler’s Fork in close proximity to the Ironton Trail and Iron Range. (Detail of Stuntz’s survey during August of 1857.)

Three were accordingly platted — one at Penoka, one at Lockwood‘s and one at the Gorge. And in order that it might be done without interfering with the regular survey, Gen. Cutler decided to place S.R. Marston who, in addition to his other accomplishments, claimed to be a full-fledged surveyor, in charge of the work, assisted by Wheelock, Smith and myself. He commenced at the Gorge, run three lines and quit, fully satisfied that he had greatly overestimated his abilities. We were certainly satisfied that he had. A drunken man could have reeled it off in the dark and come nearer the corner than he did. He was a complete failure in every thing he undertook. He left in the fall after the failure of the Sioux Scrip plot. Where he went I never knew. George E. Stuntz was subsequently put upon the work, which he was not long in doing, after which he rejoined Albert on the main work. This main work, however, for the completion of which we were all so anxious, was very much delayed, the cause for which we did not at the time fully understand, but we did afterwards. J.S.B.

Penokee Survey Incidents: Number II

February 12, 2015

By Amorin Mello

The Survey of the Penoka Range and Incidents Connected with its Early History

—

Number II.

Friend Fifield:– Notwithstanding the work upon the Range was delayed very much on account of the unwoodsman like conduct of the Milwaukee boys, referred to in my first communication, yet it did not cease,- the company having a few white men, previous employed, as well as a large number who were “to the Mannor born” that did not show the “white feather” on account of the mosquitos, gnats, gad flies and other vermin with which the woods were filled,– most of whom remained with us to the end.

Prominent among these last named was Joseph Houle, or “Big Joe” as he was usually called,– a giant halfbreed, (now dead), who was invaluable as a woodsman and packer. Some idea of Joe’s immense strength and power of endurance may be formed from the fact that he carried upon one occasion the entire contents, (200 lbs.) of a barrel of pork from Ironton to the Range without seeming to think it much of a feat. Among the party along on this trip was a young man taking his first lesson in woodcraft, whose animal spirits cropped out to such a degree that the leader caused to be placed upon his back a bushel of dried apples (33 lbs.), simply to keep him from climbing the trees, but before he reached the Range, his load, light as it was, proved too much for him, when Joe, in charity, relieved him of it, adding it to his own pack – making it 233 lbs. This was, without doubt the largest pack ever carried to the Range by any one man. There was an Indian, however, in the employ of the company, as a packer, (“Old Batteese“), who left Sidebotham‘s claim one morning at 7 A.M., went to Ironton and was back again to camp at 7 P.M. with 126 lbs. of pork, having traveled forty-two miles in ten hours. This was in July ’57, and was what I considered the biggest day’s work ever done for the company. The usual load, however, for a packer, was from sixty to eighty pounds.

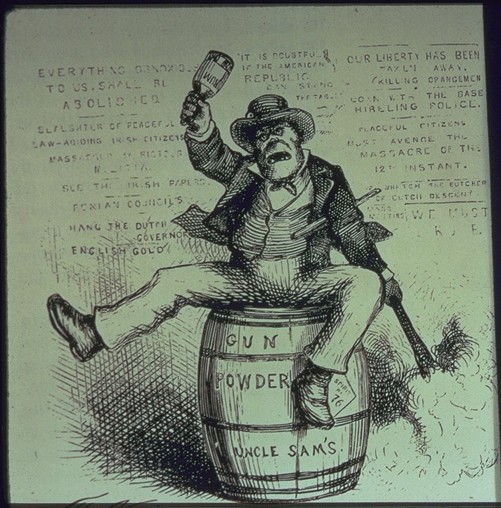

Ironton townsite claim at Saxon Harbor with trails to Odanah and the Penoka Iron Range. (Detail from Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records)

The halfbreeds were sulky and mutinous at times, giving us some trouble, until Gen. Cutler, who was a strict disciplinarian, gave them a lesson that they did not soon forget and which occurred at follows:

The General and myself left Ironton just before the removal of our supplies to Ashland, with four of these boys, with provisions for the Range, to be delivered at Lockwood’s Station. But upon reaching Sidebotham’s, two of them refused to proceed any further, threw down their packs, and started on their return to Ironton. The General’s blood was up in a moment, and directing me to remain with the others until he returned, at once started after them. Reaching Ironton at 11 A.M., about an hour after their arrival, they were quite surprised at seeing him, but said nothing. The General at once directed Duncan Sinclair, who had charge of the supplies at that time, to make up two packs of one hundred pounds each, with ropes in place of the usual leathern strap, which was quickly done, the “rebels” looking sullenly on all the while. When all was ready he drew his revolver and ordered them to pick them up and start. They did not wait for a second order, but took them and started, he followed immediately behind. Nor did he let them lay them down again until they reached Lockwood’s at sunset, a distance of twenty-six miles. – That evening they were the most completely used up men I ever saw on the Range, and from that time forward were as submissive and obedient as could be desired. After that we never had any trouble. It was a lesson they never forgot.

Among the whites referred to in this article, was James Stephenson, a young man from Virginia, who came up with Stuntz as a surveyor. He was of light build, wiry and muscular – full of fun – very excitable and nervous, – but a good man for the woods. He had some knowledge of the compass, but not sufficient education to make a good surveyor. “Jim” got lost once and was out three days before he came into camp, which he did just as the party was starting out to find him. “Jim” would not have made a good rope walker. He was no Blondin. On the ground he was all right, but let him attempt to cross a stream of water, be it ever so small, upon a log, no matter if the log was six feet in diameter, and he would fall in sure. He fell in twice while lost and came near perishing with wet and cold in consequence of it. He left the company in the fall of ’57.

But the best man we had on the range that summer, as a surveyor, (except Albert Stuntz, and I very much doubt if he could beat him), was George E. Stuntz, a nephew of Albert’s, known among the boys as “Lazarus.” He was tall and slim, with a long thin face, blue eyes, long dark brown hair, stooped slightly when walking; walked with a swinging motion, spoke slow and loud – was fond of the woods, prided himself on his skill with the compass, and was, I think, the laziest man at that time in the county, except “Sibly,” who could discount him fifty and then beat him. But notwithstanding all this Albert could not have completed his survey that season without him. His lines never required any corrections. George was a singer – or thought he was, which is all the same. The recollections of some of his attempts in this line almost brings tears to my eyes from laughter, even now. Nearly every night in camp, the boys, after getting into a position where they could laugh without his seeing them, would coax him to sing. His favorite piece was a song called “The Frozen Limb.” What it meant I have no idea, and do not think he had. One verse of this only can I recall to mind, which ran as follows:

“One cold, frosty evening as Mary was sleeping –

Alone in her chamber, all snugly in bed. – She woke with a noise that did sorely affright her.

‘Who’s that at my window?’ she fearfully said.”

You can easily imagine how this would sound when sung through the nose in the hard shell style – each syllable ending with a jerk, something like this:

“Who’s-that-at-my-win-dow-she-fear-ful-ly-said-ud.”

George had a suit of clothes for the woods made of bed ticking, cap and all complete – all but the cap in one piece. The cap was after the “Dunce” pattern, ie, it ran to a point. The stripes instead of running up and down as they should have done, ran diagonally around him, giving him the appearance of a walking barber’s pole. He was a nice looking boy – he was.

Shortly after donning this beautiful suit, while crossing the Range, he suddenly found himself face to face with a full grown bear. It was no doubt a surprise to both parties,– it certainly was to the bear. For he took one square look and left for distant lands at a speed which, if kept up, would have carried him to Mexico in two days. “Not any of that in mine” was probably what was passing through his massive brain, but he made no sign. The boys who were surveying some fifteen miles south of the Range claimed to have met him that day, still on the jump. J.S.B.

Penokee Survey Incidents: Number I

February 8, 2015

By Amorin Mello

The Ashland Weekly Press is now the Ashland Daily Press.

November 10, 1877

For the Ashland Press

The Survey of the Penoka Iron Range and Incidents Connected With Its Early History.

—

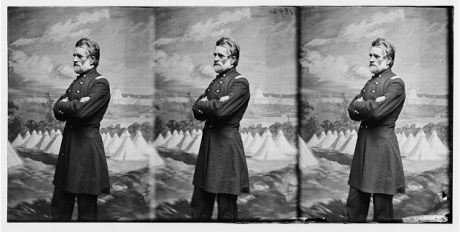

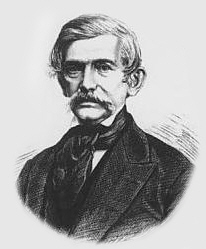

James Smith Buck (1812-92) “For 19 years, Buck was a building contractor, erecting many of the city’s earliest structures. He is best known for his writings on early Milwaukee history. From 1876 to 1886, he published a four-volume History of Milwaukee, filled with pioneer biographies and reminiscences.” (Forest Home Cemetery)

Friend Fifield:- Being one of the patrons and readers of your valuable paper, and having within the past year noticed several very interesting and well written articles entitled “Early Recollections of Ashland” in its columns, and more particularly one from a Milwaukee correspondent, in a recent number, in which my name, with others, was mentioned as having done some pioneer work in connection with your young city, I thought that a few lines in the way of a “Reminiscence” from me as to how and by whom the Penoka Range was first surveyed and located, might be interesting to some of your readers,- if you think so, please give this a place in your paper and oblige.

Truly Yours,

J.S. Buck.

I first visited Lake Superior in the month of May, 1857, in the interest of the Wisconsin and Lake Superior Mining and Smelting Co., a charter for the organization of which had been procured the previous winter.– This company was composed of the following gentlemen: Edwin Palmer, Gen. Lysander Cutler, Horatio Hill, Jas. F. Hill, Dr. J.P. Greves, John Lockwood, John L. Harris, John Sidebotham, Franklin J. Ripley and myself. Edwin Palmer, President, J. F. Hill, Secretary – with a capital of (I think) $60,000. Our first agent was Mr. Milliam Herbert, with headquarters at Ironton, where some five thousand dollars of the company’s money was invested in the erection of a block-house and a couple of cribs intended as a nucleus for a pier – and in other ways – all of which was subsequently abandoned and lost – the place having no natural advantages, or unnatural either, for that matter.– But so it is ever with the first and often with the second installments that such greenies as we were, invest in a new country; for so little did we know of the way work was done in that country that we actually supposed the whole thing would be completed in three months and the lands in our possession. But what we lacked in wisdom, we made up in pluck — neither did we “lay down the shubble and de hoe,” until the goal was reached and the Penoka Iron Range secured – costing us over two years time and $25,000 in money.

The company not being satisfied with Mr. Herbert as agent, he was removed and Gen. Cutler appointed in his place, who quickly selected Ashland as headquarters, to which place all the personal property, consisting of merchandise principally, was removed during the summer by myself upon Gen. C.’s order – and Ironton abandoned to its fate.

~ Captain Robinson Derling Pike (Bayfield 50th anniversary celebrations)

The company at this time having become not only aware of the magnitude of the work they had undertaken, but were also satisfied that Ashland was the most feasible point from which to reach the Range, as well as the place where the future Metropolis of the Lake Superior country must surely be — notwithstanding the “and to Bayfield“ clause in that wonderful charter of H.M. Rice.

The cost of getting provisions to the Range was enormous – it being for the first season all carried by packers – every pound transported from Ashland to the Range costing from five to eight cents as freight.

This was my first experience at surveying as well as Mr. Sidebotham’s, and although I took to it easily and enjoyed it, he never could. He was no woodsman; could not travel easily, while on the other hand I could outwalk any white man except S.S. Vaughn in the country. He was then in his prime and one of the most vigorous and muscular men I ever met; but I think he will tell you that in me he found his match.

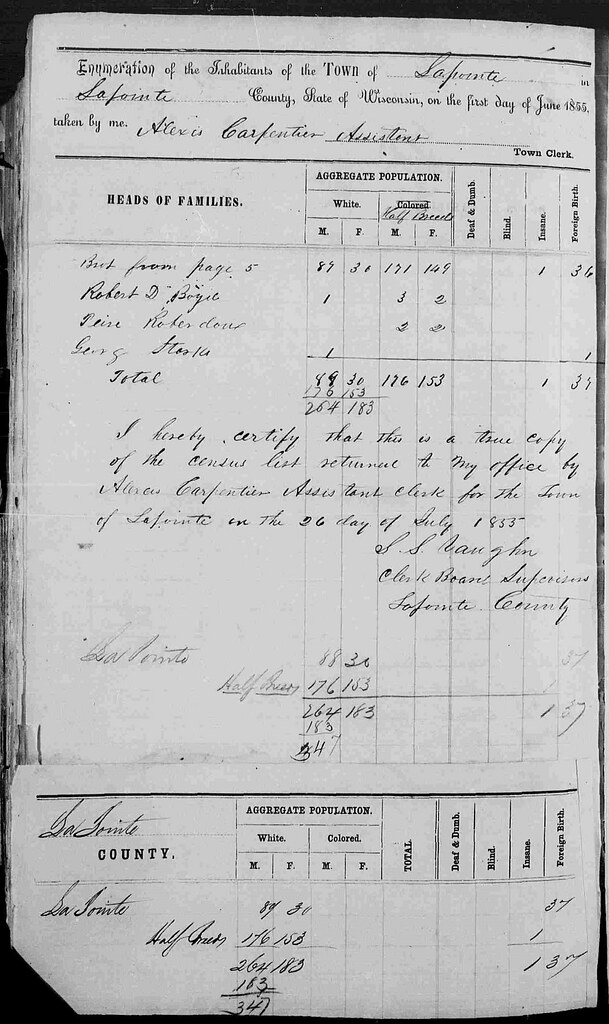

By our contract with Albert Stuntz we were not only to pay him a bonus equal to what he received per mile from Government, but we were also to furnish men for the work and see him through. In accordance with this agreement some eighteen men and boys, to be used as axemen and chainmen, were brought up from Milwaukee who were as “green as gaugers” and as the sequel proved, about as honest. A nice looking lot they were, when landed upon the dock at La Pointe, out of which to make woodsmen. I think I see them now, shining boots,– plug hats, with plug ugly heads in them, (at least some of them had), the notorious Frank Gale, Mat. Ward and one or two other noted characters being of the number. Their pranks astonished the good people of La Pointe not a little, but they astonished Stuntz more. One half day in the woods satisfied them – they were afraid of getting lost. In less than two weeks they had nearly all deserted and the work had to be delayed until a new squad could be obtained from below.

But I must close. In my next I will give you an account of my life on the Range. J.S.B.

An Interesting Family History

February 2, 2015

By Amorin Mello

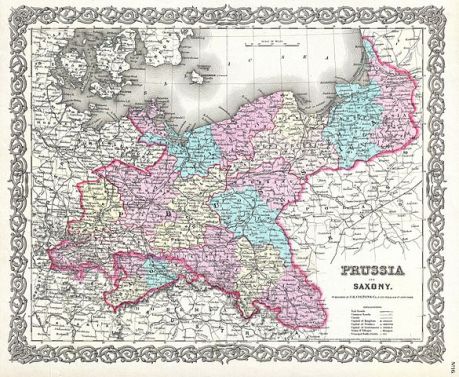

1856 Colton Map of Prussia and Saxony, Germany (WikiMedia.org).

This is a reproduction of “An Interesting Family History” from The Jews of Illinois : their religious and civic life, their charity and industry, their patriotism and loyalty to American institutions, from their earliest settlement in the State unto the present time, by Herman Eliassof, Lawrence J. Gutter Collection of Chicagoana (University of Illinois at Chicago), 1901, pages 383-386:

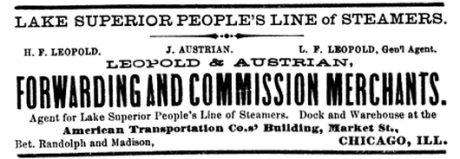

The goal of this post is to provide genealogical information about the illustrious Austrian and Leopold families as a companion to the Joseph Austrian Memoir and as a reference for future stories. In this post, we will explore events within and outside of the Chequamegon region for context about this family’s history. We recommend reading this Opinion by Andrew Muchin, director for the Wisconsin Small Jewish Communities History Project, for more information about Jewish immigration to Wisconsin in general. Coming soon to Chequamegon History, we will explore some of Julius Austrian’s adventures and his impact upon the Village of La Pointe, the La Pointe Iron Company of the Penokee Mountains, and the Lake Superior Chippewa.

——-

AN INTERESTING FAMILY HISTORY.

——-

The two families of Austrian and Leopold have been prominent in Chicago for many years. They came to Chicago from the Lake Superior region and formed the Lake Michigan and Lake Superior Transportation Co., engaging in freight and passenger transportation on Lake Michigan and Lake Superior, to Mackinac, Sault Ste. Marie and Duluth and did an extensive business. For a number of years, until recently, their luxuriously furnished passenger boat, Manitou, has been extensively patronized by summer pleasure seekers, who wished to enjoy the cool and delightful climate of the Lake Superior region. The boat was then sold to a company, in which Mr. Nathan F. Leopold still holds the largest interest. Mr. N. F. Leopold is the son of one of the Leopold brothers who settled in Mackinac in the early forties, and were the first Jews in that region. He married a daughter of the late Mr. Gerhard Foreman, who is related to the Greenebaum family, and who was a prominent banker of Chicago, the founder of the Foreman Bros. Banking Co., a. very popular financial institution of today.

The history of this old Jewish family, favorably known as successful merchants in the Lake Superior region and in Chicago, appeared in 1866, in the Portage, Mich., Gazette, and was copied in the American Israelite under date of April 13th, 1866. We believe that the history of this popular and highly respected family will be read with interest by their many relatives and friends, and we therefore publish it here. They were brave, honest and upright business men, and the story of their pioneer life in a sparsely settled region, of their struggles, hardships and ultimate success will serve as an encouraging example for many a young beginner.

Following is their history as we find it in the American Israelite:

A BAND OF BROTHERS.

Dissolution of the Oldest Merchant Firm on Lake Superior – The Leopold Brothers – Sketch of their Operations – A Pioneer History.

Abraham Isaac Oestreicher &

Malka Heule

Falk Austrian

Julius Austrian

Marx Austrian

Babette Austrian

Joseph Austrian

Ida Austrian

Fanny Austrian

Samuel Solomon Austrian

Bernard Austrian

Mina Austrian

Jette H.S.H Freudenthaler

Louis F. Leopold

Aaron F. Leopold

Henry F. Leopold

Samuel F. Leopold

Hannah Leopold

Karolina Freudenthaler

Ascher Freudenthaler

In our last issue we made a brief notice of the dissolution of the well known firm of Leopold & Brothers, doing business in Hancock, Chicago and Eagle River, the oldest business firm on Lake Superior after a successful existence of over twenty years. The firm has been composed of Louis F., Henry F., Aaron F., and Samuel F. Leopold and Joseph, Julius and Samuel Austrian, the latter being the last admitted partner, and not so intimately connected with the history of the firm. From the very inception of business transactions within the wilds of Lake Superior down to the present day, the firm of the brothers has been identified with the struggles, hardships, successes, and all the varying interests of the country, have participated with its good and ill fortunes, many times carrying burdens that less confident competitors shrank from bearing; never once fearing that all would be well in the end, and after gathering a rich reward retired from the field, leaving an untarnished history, and brilliant record as an incentive to their successors.

~ Joseph Austrian Memoir

Louis Leopold + Babette Austrian

Hannah Leopold + Julius Austrian

Henry Leopold + Ida Austrian

Samuel Leopold + Babette Guttman

Joseph Austrian + Mary Mann

Solomon Austrian + Julia Mann

The Messrs. Leopold are natives of the little town of Richen, in the Great Duchy of Baden, Germany, and there received the elementary education which fitted them to become the shrewd and successful merchants they have proven to be. They first began business life as clerks in an ordinary country store, as it may not be inaptly termed, as Richen was but a small place, having a less population than either Hancock or Houghton, here on Portage Lake.

Early in the year 1842, Louis, the elder brother, who has since become the “father” of the firm, left his home to try his fortunes in the New World, with a stout heart, and but a very moderate amount of means whereon to build up a fortune, upon arriving in this country he very shrewdly foresaw that the great West, then but just attracting attention, was the most promising field for men of enterprise and limited capital, and instead of joining in the precarious struggle for position and existence, even so peculiar to the crowded cities of the Eastern states, he at once wended his way to Michigan, then considered one of the Western states.

~ Joseph Austrian Memoir, pg. 9

Early in the year 1843 he opened a small depot for fishermen’s supplies on the island of Mackinac, providing for them provisions, salt, barrels, etc., and purchasing the fish caught, and forwarding them by vessels to better markets. The business could not have been a very extensive one, for when joined by his brothers three years afterward, their united capital is stated as being but little more than $3,000, but which has since been increased by their energy, prudence and foresight, at least one hundred fold.

In the year 1844, Louis was joined by his brother Henry (Aaron and Samuel serving their time in the store of Richen), who for a short time became his assistant at Mackinac. At that time there was but one steamboat plying on the headwaters of Lake Huron and Michigan, the old General Scott, which made regular trips between Mackinac and Sault Ste. Marie.

By the 1850’s the Leopolds, Samuel, Henry, and Aaron, and their brother-in-law Julius Austrian had moved westward from Mackinac into Lake Superior and had settled in the Wisconsin island town of La Pointe, not too far from present-day Duluth. They helped also to found the nearby mainland town of Bayfield. Nevertheless the Leopolds and Austrians were not Wisconsin’s Jewish pioneers; Jacob Franks of Montreal had bought peltries and traded with the Indians since the early 1790’s using Green Bay as his base. The town, the oldest in that part of the country, was strategically located on the water highways linking the Mississippi to the Great Lakes and the eastern tidewater. At first Franks was an agent for a Canadian firm; by 1797 he was on his own. He enjoyed several years of prosperity before the game, the furs, and the Indians began to fade away and before he had to cope with the competition of John Jacob Astor’s formidable American Fur Company. Franks was an innovative entrepreneur. Around the turn of the century he built a blacksmith shop, a dam for water power, a saw and grist mill, ran a farm and began a family of Indian children, before he finally went back to Mackinac and then to Montreal where he rejoined his Jewish wife.”

~ United States Jewry, 1776-1985, Volumes 1-2 by Jacob Rader Marcus, pg. 94

Shortly after his arrival at Mackinac, Henry conceived the idea of going to La Pointe with a small stock of goods, and attending the Indian payment, an enterprise never before undertaken by a trader from below the Sault. At that time Lapointe was a much larger place than it is now, was the principal station of Lake Superior, of the American Fur Company and the leading business point above the Sault. Every fall, the government disbursed among the Indians some $40,000 to $50,000, which before the arrival of the Leopold Brothers found its way almost entirely into the coffers of the Fur Company.

In the latter part of the spring the brothers left Mackinac on the old General Scott, and went to the Sault with their goods, and after much difficulty succeeded in chartering the schooner Chippewa, Captain Clark, to take them to Lapointe for $300. There were but four small schooners on Lake Superior that season, the Chippewa, Uncle Sam, Allegonquin and Swallow. The trip from the Sault to Lapointe occupied some three weeks, but one stop being made at Copper Harbor, which was then beginning its existence. The building of Ft. Wilkins was then going on. Little or no thought of mining then occurred to the inhabitants, and did not until two or three years subsequently.

Arrived safely at Lapointe, they at once opened a store in opposition to that of the Fur Company, and were, much to the surprise of the latter, the first white traders who undertook an opposition trade with the Indians. They sold their goods for furs, fish, etc., and prospered well. In the fall they were joined by Julius Austrian (now at Eagle River) and Louis leaving him with Henry, returned to Mackinac.

Before Minnesota became a territory in 1849 it was for a time part of Wisconsin and Iowa territories. In Minnesota as in most states there was a wave of Jewish pioneers who came early, often a decade or more before some form of Jewish institutional life made its appearance. Jewish fur traders roamed in the territory from the 1840’s on, bartering with the Indians on the rivers and on the reservations. They were among the first white settlers in Minnesota. Julius Austrian had a trading post in Minnesota in the 1840’s and he may once have owned the land on which Duluth now stands. In 1851 in the dead of winter he drove a dog sled team loaded with hundreds of pounds of supplies into St. Paul; his arrival created a sensation.”

~ United States Jewry, 1776-1985, Volumes 1-2 by Jacob Rader Marcus, pg. 100-1

In the summer of 1845 Henry also returned to Mackinac, leaving Julius to attend to the business at Lapointe. He remained in Mackinac until the year 1846, when Aaron and Samuel came out from Germany and joined them at that place. The four brothers at once united their fortunes; in fact in all their business career they do not appear to have thought of dividing them. Everything they had was, from the outset, common property, and each labored for the general welfare. They appeared to have fully understood the truthfulness of the adage, that, in “Unity there is strength,” and however varied and scattered may have been their operations, the profits went into the general fund.

In the season of 1846 Henry and Samuel went to Green Bay, and opened a store in Follett’s block, remained there until early in 1848, but did not succeed as well as they anticipated. Green Bay was then a miserable place in comparison with what it is now, and its growth very much retarded by the grasping policy of the site owners, John Jacob Astor and Mr. Whitney, a brother of the present postmaster. They would not sell lots at anything near what was considered a reasonable figure, and the result was that after many vain endeavors to secure property very many business men left for other places, holding out better inducements for settlement. While at Green Bay, Samuel began the study of the English language, under the tutelage of a young Methodist minister who considered himself liberally rewarded by return instruction in the German language.

“This represents the home of Julius and Hannah Austrian, after their marriage in the spring of 1848. Premises located at La Pointe, Madeline Island, Lake Superior. Resided there 19 years, happy and contented among Indians, Half-breeds and two Missionaries who represented the inhabitants of the island. Photograph taken summer of 1850.”

~ Julius Austrian Papers (Madeline Island Museum)

Solomon Austrian“also went up to La Pointe by advice of brother Julius where he stayed but a short time…”

~ Joseph Austrian Memoir, pg. 76

Early in 1847, Joseph Austrian, the subsequent brother-in-law of the Leopolds, came out from Germany, and joined his brother, Julius, at Lapointe, where he remained until the next spring, when he joined Henry Leopold at Eagle River, who had opened a small store in an old stable, the habitation of one cow. A partition was put up, and about two-thirds of her ladyship’s parlor fitted up for the sale of dry goods, groceries, etc. The shanty stood on the lot now owned by John Hocking, the second from the corner in the turn of the road down to the old bridge across Eagle River.

Was Simon Mandelbaum of Eagle River related to M.H. Mandelbaum of Bayfield?

There was then but one opposition store in Eagle River, that of Messrs. Senter and Mandlebaum, with whom Henry and Joe entered into lively competition for the trade of the place.

The same season Samuel joined Aaron and Louis at Mackinac, where their business had materially increased, and remained there until the season of 1855, when they left and returned to Lake Superior. Louis had previously left and established himself at Cleveland, where he remained until he went to Chicago in the fall of 1862. During this period he acted as the purchasing agent of the brothers on the lake.

Stories about the early days of the Keweenaw copper mining industry are told in the Memoirs of Doodooshaboo (Joseph Austrian).

In the fall of 1855 Samuel started a branch store at Eagle Harbor in a small shanty not more than twenty feet square, situated on the lot now owned by Hoffenbecker, and the shanty now forms a part of his building. At the time there were five mines working in that vicinity, as follows: Copper Falls, S. W. Hill, agent; Northwestern (Pennsylvania), M. Hopkins, agent; Summit (Madison), Jonathan Cox, agent; Connecticut (Amygdaloid), C. B. Petrie, agent.

The Copper Falls and Northwest were the two great mines of the District, the others doing but little beyond exploration at that time.

In 1856 Samuel bought out Upson and Hoopes, who had been doing a good business in the building now occupied by Messrs. Raley, Shapley & Co., and was that season joined by Aaron, who, since leaving Mackinac, had been spending his time with Louis, in Cleveland. Samuel was appointed postmaster at Eagle Harbor, and acceptably filled the office till his departure in 1859.

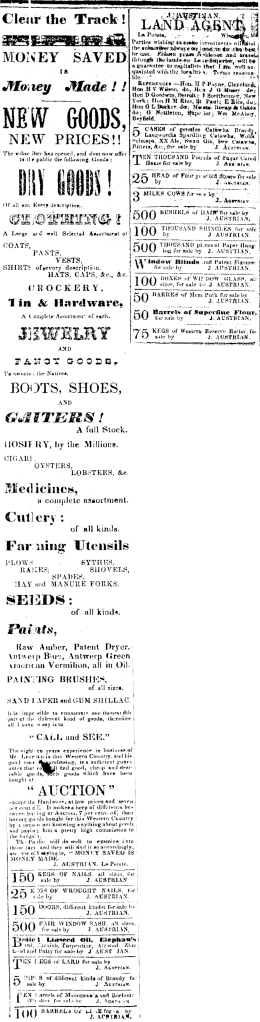

Julius Austrian advertisements

(Bayfield Mercury, August 22nd, 1857)

The three brothers, Henry, Samuel and Aaron, and their brother-in-law, Jos. Austrian, might now be said to be operating in the same field with the elder brother, Louis, at Cleveland, as their ever wide-awake purchasing agent. For a year or two they prospered as well as they could desire, but the hard times of 1857-8 tried them pretty severely, but by the most adroit management they came through safely. At Eagle River, in 1857, there were four mines at work, the Garden City, Phoenix, Bay State and Cliff. This was after the great silver excitement at the Phoenix, and when the reaction had fully set in. The assessments were grudgingly paid, if at all, and the workmen at the mine that winter were paid in orders on Leopold Brothers, who paid them in goods and currency. To enable the company to get along as easily as possible they took thirty day drafts on the treasurer in Boston, which were paid when due and presented. As the winter passed, the time of the drafts were extended from thirty to sixty, ninety, and finally to one hundred and twenty days, and in the spring, the firm was astonished by a notification that the drafts had gone to protest. The mine then owed them about $20,000, a large sum, especially when it is considered that they were also carrying nearly $10,000 for the Garden City Mine, which was also struggling along like the Phoenix.

The first news received by the public of the protesting of the drafts was communicated by the clerk of one of the steamboats, and created no small amount of excitement, especially among the employees of the mine, who naturally became fearful and clamorous for their back pay. The Leopold Brothers told them to go on and work, and they would be responsible for their pay. This quieted them, and the work of the mine continued as before.

Upon receiving information of the protesting of the Phoenix drafts, Samuel was at once dispatched to Boston to consult with the company about their payment. To secure themselves they could have attached the mining property, improvements and machinery, but such was their confidence in the integrity of the agent, Mr. Farwell, President, Mr. Jackson, and Secretary, and Treasurer, Mr. Coffin, that this was not done. Upon his arrival in Boston, Samuel found that Mr. Farwell had held a consultation with the Directors, and in his most emphatic manner demanded that Messrs. Leopold should be reimbursed the money they had advanced for the mine.

~ The Mining Magazine: Devoted to Mines, Mining Operations, Metallurgy, &c., &c., Volume 2, 1854, pg. 404.

Another meeting was called and Samuel presented a statement of the amount due his firm, and inquired what they intended to do. It was difficult for them to say, and after many long consultations no definite course of action was decided upon. Believing that delays were dangerous Samuel proposed that he and his brothers would take the property in satisfaction of their demand, pay off the Company’s indebtedness, amounting to nearly $10,000, and perhaps pay them a few thousand dollars on the head of the bargain.

Another consultation followed this offer, and it was finally concluded that if a merchant firm considered the property sufficiently valuable to pay therefor nearly $40,000, it must be worth at least that much to the company. Some three thousand shares of Phoenix stock had been forfeited for the non-payment of an assessment of $1.50 per share, and these shares were offered Mr. Leopold in satisfaction of his claim. He, of course, declined, saying he would take the whole property, or nothing. Another consultation was held and a meeting of stockholders was called, an assessment was levied and In a few days enough paid in to liquidate his demands, and he started for home mentally determining that in future the Phoenix should give sight drafts for all. future orders, and that they would no longer assume, or be identified with its obligations. It required no small amount of finesse to make the discouraged stockholders of the Phoenix believe that there was a sufficiently valuable property to further advance $2 or $3 per share on its stock, but the cool offer to take its property for its indebtedness, completely assured them and saved the Messrs. Leopold their $20,000.

But it is said ill fortune never comes singly; and this was true of the affairs of Leopold & Brothers. Samuel had scarcely arrived in Cleveland when Louis informed him that their Garden City drafts had been protested and the same night he hurried on to Chicago to provide security for the indebtedness. Arriving there he did not find the Company as tractable as the Phoenix, and after much parleying found the best they were willing to do was to give him a mortgage on their stamp mill, as security for the $10,000. Very correctly deeming this insufficient, he returned home, and got out an attachment for the whole property of the Company. This had the desired effect, and the claim was secured by a mortgage and the attachment withdrawn. Shortly afterward the mine passed into the hands of a new party of men, with Judge Canton at their head, and in a short time the claim was satisfactorily adjusted.

In 1858, the firm had much difficulty in collecting their orders on the mines in the vicinity of Eagle Harbor, and it was finally determined to sell out their store and build up a business elsewhere. S. W. Hill, Esq., had then left the Copper Falls and assumed the direction of the Quincy Mine here at this place. He foresaw that Portage Lake, possessing as it did so many natural advantages, would eventually become the grand business point or the copper region, and with his accustomed energy began the laying out of the town site now occupied by the village of Hancock. Soon after this was done he wrote to the Messrs. Leopold, urging them to come over and open a store there, but they did not give the offer much consideration that year, as nearly everybody in Keweenaw County ridiculed the idea of Portage Lake ever becoming anything of a place.

That year, however, they sold out their business at Eagle Harbor, and removed to Eagle River, where Samuel was for the second time appointed Postmaster, and their business conducted by him and Jos. Austrian. Their present store site at Eagle River had been previously purchased, and additions annually made to their main building, as their business demanded, until they were of a much greater extent than the original frame.

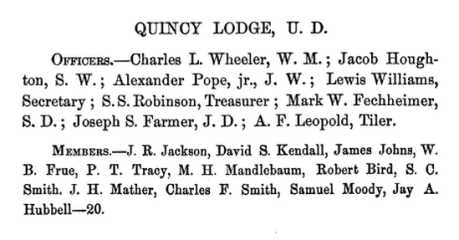

Aaron Leopold was the first Tyler of the Quincy Lodge No. 135 in Hancock. M.H. Mandelbaum was a member.

In the summer of 1859, Jos. Austrian, who was the building man of the firm, came over from Eagle River to Hancock with Geo. D. Emerson, C. E., and selected a site for their new store, and chose the lots on which now stands the Mason House and the Congregational Church, and the dock front now owned by Little, Heyn & Eytenbenz, but Louis, who came up about that time, changed to the present site, deeming the other too remote from what would be the business center of the town. This was judged from the line of the road coming down from the mine, and the location of the Stamp Mill, around which he naturally concluded the workmen’s dwellings would cluster. In this he was slightly mistaken, though the real difference was unimportant; we give it merely to show how easily the most careful and calculating men may make a mistake.

Transactions of the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons, of the State of Michigan, at Its Annual Communication, 1861, pg. 71.

After the site was determined upon, building was commenced, but as their faith in the future growth of the place was small, they did not propose to erect a large store, or even construct a substantial cellar underneath. Mr. Hill, hearing of their intention, at once paid them a visit and strongly protested against it. “This is going to be a leading town,” he said, “and I want a good large store, and a stone cellar underneath it.” He carried the day, and a larger building was completed, which two years afterward was too small for the business, even with the addition of a large warehouse for storing additional supplies.

As soon as the building was commenced, Louis began to send up goods from Cleveland, and Aaron came over from Eagle River to take charge of the new business. He scarcely reached here before the goods arrived, and were stored in the building before it was closed in, and he for several weeks had to make his bed on the goods virtually in the open air. As this was in the fall of the year, it was not pleasant, as may be at first supposed. Since then their principal business has been done at Hancock, the old head concern at Eagle River having been a branch.

Additional sources about this festive celebration for the Freudenthaler family in Richen have not been located yet.

In the fall of 1861, Aaron concluded to visit his home in Germany, to attend the golden wedding anniversary of his parents, and Samuel came over from Eagle River to take his place in the store. The celebration of the golden wedding was the grandest event which had happened in the little town of Richen for fully one hundred years, and, probably, will not be equaled in the present century. It would be impossible within the limits of this article to give a full description of the proceedings on that festival occasion, suffice it to say, that all the inhabitants of Richen and the neighboring towns, to the number of full five thousand assembled, and under the guidance of the mayor and municipal officers, for three days kept up a continuous round of merry-making and rejoicing. On the anniversary wedding day a procession over a mile in length waited upon the “happy couple,” and escorted them to the church, where appropriate and imposing services were performed. In the name of his brothers Aaron presented the church with a copy of the Sacred Writings, beautifully engrossed on parchment, which, with its ornamented silver case, cost over $600. All the halls and hotels were opened to the public, where for three days and nights they feasted, drank and danced without intermission and free of expense. The celebration of this golden wedding cost the brothers over $5,000, but which they rightfully considered the grandest event in their history.

In the fall of 1862, Joseph Austrian joined the firm at Hancock, and Louis removed from Cleveland to Chicago, which point they had concluded would soon monopolize the trade of Lake Superior. In the spring of 1864 he commenced a shipping business in that city, and early in the following winter was joined by Jos. Austrian, and the purchase of the propeller Ontonagon effected, and a forwarding and commission business regularly organized. Lately they have purchased the light-draft propeller Norman, intending it to run in connection with the Ontonagon.

While this was the end of Julius Austrian’s presence at La Pointe, he was still attached to the region for the remainder of this life by social ties and legal affairs. Julius eventually moved to St. Paul and became President of the Mount Zion Temple.“The Austrians retained their generous spirit even after moving to St. Paul for it was on a mission to the poor with a cutter full of good things to eat that Mr. Austrian was run over by a beer wagon (we don’t have them nowadays) and killed.”

~ The Lake Superior Country in History and in Story by Guy M. Burnham, 1996, pg. 288As aforementioned, Moses Hanauer was son to Moritz Hanauer, elementary educator of the Leopold brothers in their hometown of Richen. Moses’ brother-in-law was Henry Smitz of La Pointe.

In 1862 their branch house at Lapointe was given up, and Julius Austrian returned to Eagle River, and, in connection with Solomon, conducted the branch at that place. The firm now is composed of Solomon and Julius Austrian and Moses G. Hanauer, who for several years has acted as bookkeeper for the firm, under the firm name of S. Austrian & Co. The Hancock firm is composed of H. F. Leopold, Joseph and Solomon Austrian, under the title of Leopold, Austrian & Bro. The Chicago firm is composed of L. F. Leopold and Joseph Austrian, under the name of Leopold & Austrian. Mr. S. F. Leopold will return to Germany, upon the opening of navigation, and spend a year in pleasure and relaxation, which he certainly merits after twenty years constant labor. Aaron will remain here during the coming summer, and in the fall will go below and establish a wholesale business in Detroit, where it is probable he will be joined by Samuel after his return from Europe.

“CHICAGO AND LAKE SUPERIOR LINE.

This line is owned in Chicago, but is included in our list with other lines plying between Michigan ports. Those enterprising and well known gentlemen, Leopold & Austrian, for many years proprietors of this line, have consolidated their navigation interests with those of the Spencer, Lake Michigan and Lake Superior Transportation Co., their boats running between Chicago and Duluth, touching at all intermediate ports in Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin. The steamers are the Peerless, J. L. Hurd, City of Duluth, City of Fremont and barge Whiting.”

~ Tackabury’s atlas of the State of Michigan : including statistics and descriptions of its topography, hydrography, climate, natural and civil history, railway and steam boat history, educational institutions, material resources, etc. (1884), pg. 23Louis F. Leopold and his sons, Asa F. and Henry F. Jr, started the first mercantile house in Duluth in 1869. Asa and Henry were the first Jewish residents in Duluth and enjoyed success as prominent businessmen.

That the Messrs. Leopold have been more than ordinarily successful in their mercantile career of over twenty years is made evident from the extent and variety of their business transactions within the past five years, and the very large amount of capital required to carry it on successfully and properly. We feel confident that the joint capital of $3,000, with which they commenced business in 1843, had been increased one hundred times by the close of the past year, and we should not be surprised if it had augmented even more than that. It has been the result of no particularly good fortune, but of persistent application in one direction, and the only exception to the ordinary course of operation which can be said to have contributed to their success, has been the remarkable unity which has pervaded all their business transactions, whether located at Mackinac, Green Bay, Lapointe, Eagle River, Cleveland, Eagle Harbor, Portage Lake or Chicago, each member of the firm has labored, not for his benefit alone, but that of the whole brotherhood.

“S. Solomon Austrian, a merchant from the copper country of Upper Michigan married Julia R. Mann, ten years his junior and not yet out of school, of Natchez, Mississippi, about 1866. Their first home was in Hancock, Michigan. In writing of her mother at a later time, Delia describes the young wife’s inexperience as she entered this strange new country, and the difficulties she had learning homemaking from her pioneer neighbors, along with her fear of Indians. Here, their first child, Bertha, was born. After two years of residence, they moved to Cleveland. In 1870, a son, Alfred S., was born in Chicago, but there is no evidence to show they were residents of that city at the time. However, they were still living in Cleveland in 1874 when twin daughters, Celia and Delia, were born.”

~ Guide to the Celia and Delia Austrian Papers 1921-1932, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

And at this partial termination of their active associations, it is with a pride which but few firms experience after so long connection, they can say that in all their twenty years’ relation with each other there has never been a disagreement to mar the harmony and unity of their operations. Whatever has been done by one, even though it did not result as anticipated, has met with the immediate sanction of the others, who had unlimited confidence in the integrity of his intentions to benefit them all. Until now there has been no division of the accumulated profits; all has been placed in one general fund, from which each has drawn as the wants or exigencies of their business demanded. Neither of them have indulged in any private outside investments or speculations, the profits of which has resulted to his own pecuniary benefit. Profit and loss has been shared alike by them all. Such unanimity of action is very rarely to be met with, especially In these modern days of “every man for himself and the devil take the hindmost,” and is, therefore, the more commendable. Although nominally dissolved, at present, we are of the opinion that after S. F. Leopold has returned from his vacation in Europe the old order of things will again prevail, for, after such a lengthy and intimate association, it will be difficult for either of them to operate independent of the rest, after such a practical verification of the truthfulness of the adage on which they founded their business existence, that “In union there is strength.”

We also copy the following letter, which, in our estimation, forms a part of and belongs to the history of the Leopold family. We understand that the son of whose birth the writer of the letter to the “Israelite” speaks, was the first Jewish child born in the northern region of Michigan:

Chicago, July 18, 1863.

Editor of The Israelite:

I have just now returned from Lake Superior, where I have found all my brothers and friends and the readers of The Israelite and Deborah in perfect good health. I cannot refrain from giving you a little history of a very noble act, the fruit of which in hereby enclosed, being a draft for $30, which you will please to appropriate to the purpose for which it has been destined, namely at a Berith which took place on a child of my brother at his house in Hancock, Lake Superior. After about forty participants had done justice to a very luxurious dinner, with the permission of Mr. Hoffman of Cleveland, the operator, a motion was made that the saying of grace should be sold, and the proceeds appropriated to some charitable purpose, whereupon Brother Samuel made an amendment that the proceeds should be sent to Dr. Wise of Cincinnati, to be appropriated by him for the monument to be erected for Dr. Rothenhelm; the sheriff, Mr. Fechheimer, seconded the motion, and the same was unanimously carried. Brother A. F. was the last bidder with $30, consequently he was the lucky purchaser, and bestowed the honor on your humble correspondent.

The act is worth imitating, and if you think it worth mentioning you may give it publicity in The Israelite and Deborah.

Yours truly,

L. F. Leopold.

They called him “Gray Devil”

January 21, 2015

By Amorin Mello

(Lewiston Saturday Journal, April 27, 1895, page 11)

(Lewiston Saturday Journal, April 27, 1895, page 11)

Transcript from the

History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin:

From Prehistoric Times to the Present Date

as published in 1881 by the Milwaukee Genealogical Society:

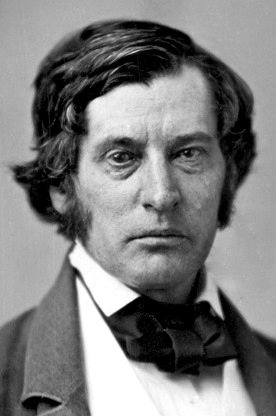

MAJOR-GENERAL LYSANDER CUTLER was born in Royalston, Worcester County, Mass., February 16, 1807. His father, Tarrant Cutler, was one of the most independent and sturdy farmers of the county, and cultivated, with the help of six boys, as they grew up, one of the largest and most rocky farms in all that stony region of hills that lies at the foot of Mount Monadnock. Here Lysander received his early education. He worked on the farm during the Summers, and attended the district school each Winter till he was 16 years old. At that age he had acquired all that could be gotten from the town schools and all other sources within his reach, and in the opinion of his father was in a dangerous state of forwardness, calculated to unfit him for the high and noble career he had marked out for him — on the farm, and he accordingly determined that his education was complete, and set him down for the coming five years as a steady hand on the farm. The young man broke out in open rebellion against this paternal edict and announced his intention to leave the homestead forever, unless his father would at least assist him to acquire an academic education. After many stormy discussions, the matter was settled by a sort of treaty, whereby, although still under parental rule, he had a roving commission to forage for himself within limits set by his father. Under this arrangement he did very little farm work except in haying, when all the boys were called home to assist. During these five years he managed to clothe himself, learn the clothier’s trade, get a fair academic education, had learnt the art of land surveying, and had acquired a very enviable reputation in the county as a successful schoolmaster, as he had fought into submission several turbulent and unmanageable schools that had heretofore made it a practice to “pitch out” such teachers as were undesirable to them. With such acquisitions, at the age of 21, he emigrated to Maine and settled in the town of Dexter, Penobscot County, in 1828. His worldly goods on his arrival consisted of a silver watch and two dollars in money. He arrived in the Winter, just as the settlement was in an uproar over a rebellion in the school that had thus far proved unmanageable and had resulted in the flogging and summary ejectment of several masters who had attempted to maintain discipline by the ferule and switch, the only means then in vogue. He immediately volunteered to keep the school out for the sum of sixteen dollars per month — no school, no pay. The school committee accepted his proposition. The first day was devoted to an examination on the part of the big boys, as to the qualification of the new master. The examination was searching, and resulted in the thorough flogging of every bully in the school and a quiet orderly session thereafter to the end of the term. Thus early established in favor at the settlement, he began the business of his life. He surveyed the land up and down the stream which flowed from a small lake having an outlet at the village, and discovered the value of the water-power which had hitherto only been roughly put to use to run a saw-mill. In 1834 he entered into a co-partnership with Jonathan Farrar, a wealthy proprietor of the township, and built a woolen mill, then the largest east of Massachusetts, which under his successful management brought him what was then deemed an independent fortune in ten years. In 1843 the mill was burned to the ground, leaving him as poor as when he started. His partner, however, drew upon his private credit and the works were speedily rebuilt and added to from time to time till 1856. At that time the village had grown to a smart manufacturing town numbering 2,000 inhabitants, nearly half of whom were dependent on him for support. The firm owned three woolen factories, a foundry, a grist-mill, a saw-mill, a large store and many tenements. The panic of that year found his business widely extended. The mills stopped, the immense accumulation of their unsold goods were sold, in some instances, at less than half their cost, the property went into other hands and the firm was ruined. Turning his back on the scenes of his active life, he came to Milwaukee in 1856.

During his New England life he took an active part in the affairs of his State. He was almost uninterruptedly a member of the Board of Selectmen of his town, served in the State Senate one term — 1839-40 — as a Whig. He commanded a regiment of troops on the border, pending the settlement of the northeastern boundary, in 1838-9. He was also active in educational matters. He was for several years one of the Trustees of Westbrook Seminary, and served on the Board of Trustees of Tufis College, during the years when it was struggling into life. He also gave his time and means to the development of the railroad system of the State, and was one of the Board of Directors of the Maine Central (then the Androscoggin and Penobscot Railroad Company) until it was built as far east as Bangor. He was generous to a fault, and for the thirty years he lived in Maine he carried an open hand and purse to all who needed. It was certainly no small thing or such a man at such a time of life to commence anew, in a strange country the strife for business success among the crowds of younger men who were thronging every avenue that opened to even a chance of good fortune.

(Pioneer History of Milwaukee: 1847 by James Smith Buck)

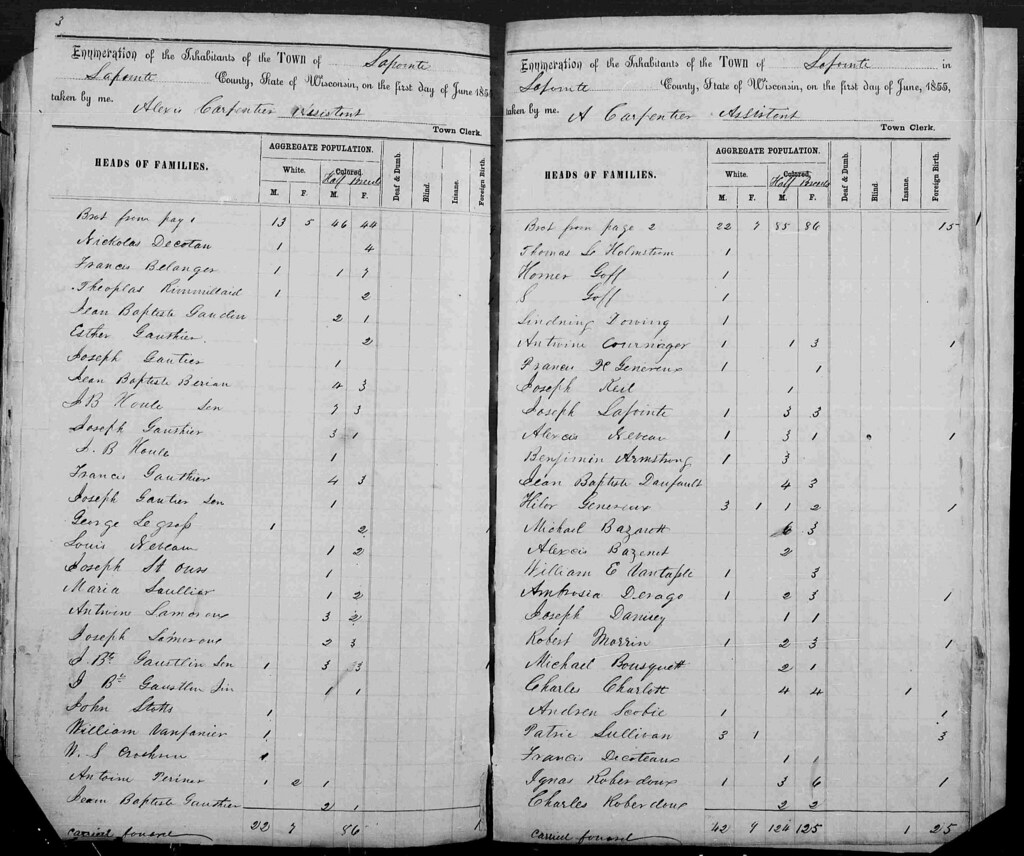

“…the population of Ashland increased quite rapidly… Of these a few remained only a short time, coming merely for temporary purposes. 1855 brought a still larger increase of inhabitants, among them M. H. Mandlebaum (now a resident of Hancock, Mich.), Augustus Barber (who was drowned at Montreal River in 1867), Benj. Hoppenyan, Chas. Day, Geo R. Stuntz, George E. Stuntz, Dr. Edwin Ellis, Martin Roehm, Col. Lysander Cutler, J. S. Buck, Ingraham Fletcher, Hon. J. R. Nelson, Hon. D. A. J. Baker, Mrs. Conrad Goeltz, Henry Drixler (father of Mrs. Conrad Goeltz, who died in 1857, his being the first death in town), and Henry Palmer.” ~ Ashland Press, January 4, 1893 (Wisconsin Historical Society)

He came to Milwaukee in answer to a letter from an old Maine friend, Horatio Hill, then one of the most active business men and public-spirited citizens of Milwaukee. He with Palmer, the Pbrothers Hercules and Talbot Dousman, Dr. Greaves and others had organized the Penokee Mining Company. The company had a sort of undefined and undefinable title to some parts of the celebrated iron deposits in the Penokee Range lying some thirty miles inland from Lake Superior, at the extreme northern point where what is now Bayfield County, juts out into the lake. The title was held by virtue of some Indian script which had been bought from the Sioux Indians, then inhabiting that region, and was by no means a perfect one, except the land was surveyed and occupied by the company and direct warrants thereby secured from the Government Land Office. Most brilliant reports had been made of the extent of the deposits and the purity of the ore. There could be no doubt that the development of these immense mineral resources would bring to the owners untold wealth. Mr. Cutler was appointed the managing agent of this prospective Wisconsin bonanza, at a fair salary, to which was added a liberal amount of the stock of the company. His first task was to perfect the title to the property, and the first step toward it was to take a personal view of the situation and the property. It was a somewhat arduous undertaking, not unfraught with danger. Excepting two or three traders and surveyors, who had stock in the company, the population, which consisted mostly of Indians and half-breeds, viewed this incursion of wealth-hunters from the lower lakes with suspicion and distrust. To add to the difficulties of the situation, other parties owning Sioux script were endeavoring to acquire a title to the mineral range. One man working in the interest of the company the year before, had been discovered, after being missed for some weeks, dead in the forest, near the range. Bruises and other indications of violence on the body gave strong ground for the belief that he had been murdered. Altogether it was a position, the applications for which were not numerous. His first trip was made in the Summer of 1857. He spent several months on the range and at LaPointe, Ashland, Bayfield and on to the Indian Reservation, acquainted himself thoroughly with the status of the company’s claims, and returned to Milwaukee. He had ascertained that the immense value of the claim had not been overestimated, and had made a further discovery, less desirable, that the company had no valid title to it, except they occupied it as actual settlers. It was determined to organize a colony sufficiently large to cover every section of the territory desired, and squat it out a sufficient time to entitle them to settlers’ warrants. The colony consisted of picked men, some from the State of Maine, who entered the employ of the company, and built their cabins as fast as the surveyor’s stakes were driven. The main cabin, which was a depot of supplies, was of importance as it was the center of the town, and as it complied with all the requirements of the law, being organized as a store and a school, it gave the company a claim to a “town plat” of a square mile. Here Colonel Cutler spent two Winters, during which he and his trusty employs endured all the hardships and dangers of a pioneer life. The nearest point where supplies could be obtained was thirty miles distant through a trackless and dense forest. All supplies were packed in on the backs of the squatters or half-breed packers who sometimes in a surly mood would lay down their burdens and return to the settlement. Nothing but the fearless pluck and dauntless courage of Colonel Cutler kept these men in wholesome awe, and insured the safety of the settlers while they remained.

Lysander Cutler’s town plat ruins at the “Moore Location” of the Lac Courte Oreilles Harvest Education Learning Project (Paul DeMain © 2013).

Lysander Cutler and the Ironton Trail (Pioneer History of Milwaukee: 1847 by James Smith Buck)

The following story is told by James S. Buck, of this city, who was one of the colony, as illustrating his mode of discipline: Late one week it was discovered that there were not sufficient supplies to last over Sunday. Colonel Cutler dispatched one of his men to the lake, with instructions to load two half-breeds and send them forward to camp the next day, he agreeing to meet them at the half-way camp and pay them for their services. They arrived before him, in a surly mood, and without waiting except to get breath took up their loads and trudged back to Bayfield. Soon after Colonel Cutler arrived and having been informed of their return set out after them. He did not overtake them on the road, but entered Bayfield a few minutes behind them, and found them at the store sitting by the fire, with their packs, which they had just thrown off, by their sides. On entering he drew up his rifle and said: “Boys, you can have just half a minute to shoulder those packs and start for the range.” In less time than was allowed they were again on the return tramp, supported in the rear by the Colonel and his rifle. At the half-way camp they begged for rest, but the only reply from their implacable guard was: “March!” with an expletive which showed undoubtedly that he was in earnest. They reached the range late at night. It was the last attempt at breach of contract on the part of the half-breeds while he remained in that region.

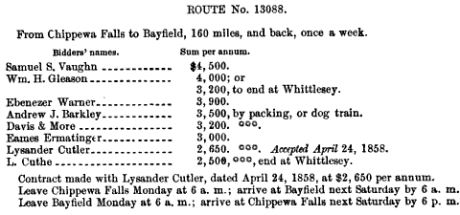

Cutler was contracted for carrying the mails in 1858 (United States Congressional serial set, Volume 1013).

In the Winter all the communication with the rest of the world was cut off, except by a weekly mail which was brought through from St. Paul by an Indian mail-carrier. Once during each Winter he made the trip on snow shoes, to St. Paul, a distance of over two hundred miles. The claim was at last secured, and a valid title to the land vested in the company. He left the region, at the end of two years, successful in this mission, and attained, while there, the general respect of all, both white and red, although his pet name among the Indians did not evince a love unmingled with fear; they called him “Gray Devil.” The dull times that followed put a long quietus on Western schemes of speculation, and Colonel Cutler’s company was laid on the shelf with many others of less merit, till more propitious times.

Cutler’s contract was not successful for long. (United States Congressional serial set, Issue 1041, Part 2).

In 1859 he engaged in the grains and commission business, in which he continued with indifferent success till the breaking out of the war.

The first gun fired on the flag seemed to rouse the full energies of his naturally pugnacious nature. It seemed as though the burdens of twenty years had fallen from his shoulders, and he showed the war-like enthusiasm of a young man of thirty instead of the more quiet demonstrations of a man who had already done the arduous work of a common lifetime. It was only in deference to the earnest protests of his friends that he did not enlist as a common soldier when the first call was made for ninety-day troops.

Colonel Cutler was commissioned as Colonel of the Sixth Wisconsin Regiment June 25, 1861. His regiment left the State July 28, and joined the forces around Washington August 7. August 29 it was attached to King’s Brigade, of which it remained a part during the war and shares in its imperishable renown as “The Iron Brigade.” During its first year of service Colonel Cutler was much of the time in command of the Brigade, and did much in perfecting it in discipline and tactics. His active service in the field commenced with the campaign of 1862. McDowell’s Division, to which the “Iron Brigade” was attached, did not participate in the peninsular battles of the campaign, being held as a reserve force to repel any overland demonstrations on the Capital, similar to that of the year before, which culminated in the first battle of Bull Run. During the earlier months of the campaign Colonel Cutler commanded the Brigade, till the assignment of Brigadier-General John Gibbons, May 2, when he again returned to his regiment. The Brigade was almost constantly on the march from point to point to avert threatened danger or mislead the enemy, till the beginning of August. On the fifth of that month the withdrawal of a part of the rebel forces from McClellan’s front, and a movement up the Shenandoah as well as toward Pope, commenced the active campaign. August 6, Colonel Cutler with his regiment and a New Hampshire regiment of cavalry penetrated into the enemy’s country as far as Frederick’s Hall Station, twenty-three miles from the junction of the Virginia Central with the Richmond & Potomac Railroad, and there tore up the track for a mile in each direction, thus cutting off the rebel communication between Richmond and Gordonsville. They also burned the depot, warehouse and telegraph office and destroyed a large amount of Confederate supplies. The expedition was entirely successful. During three days and one half the regiment had marched ninety miles, and were, when they struck the railroad, thirty miles from any support. It returned without the loss of aman. General Gibbon in his official report commended the regiment and Colonel Cutler as follows: “Colonel Cutler’s part in the expedition was completely successful. I can not refer in too high terms to the conduct of Colonel Cutler; to his energy and good judgment, seconded as he was by his fine regiment, the success of the expedition is entirely due.” On the 19th of August General Pope commenced his retreat. The “Iron Brigade” was for nearly ten days within sight of the enemy as they slowly worked their way up towards Washington, avoiding as much as possible any collision with the troops during its maneuvers to outflank Pope and if possible intercept him in his march to the defense of the threatened Capital. On the twenty-eighth having so far out-maneuvered him as to have separated the divisions of the army too far for support, the division of Longstreet fell upon the “Iron Brigade” which was marching toward Centerville on the Gainesville road. The Federal troops were outnumbered three to one, but they held the enemy in check till night put an end to the carnage which marked it as one of the most severe engagements of the war. How Colonel Cutler and Colonel Hamilton of Milwaukee bore themselves on that bloody field has been detailed in a previous chapter. They were severely wounded. Colonel Cutler had his horse shot under him, and was wounded by a minnie bail which passed entirely through his thigh, His wound was dangerous and kept him from active service till November 5, when he returned to the front and took command of the Brigade which he retained till the twenty-second, when General Sol. Merideth, who had been appointed Brigadier-General, assumed the command and he again returned to his regiment. At the battle of Fredericksburg he again led the “Iron Brigade,” being put in command during the action, after the Brigade had crossed the Rappahannock, and taken position in line of battle. Soon after he was appointed Brigadier-General, to date from November 29, I862, and assigned to the Second Brigade, First Division, First Army Corps. His Brigade with the “Iron Brigade” comprised the division commanded by Wadsworth. The corps was commanded by Major-General Reynolds. He fought through the Chancellorsville campaign, his Brigade covering the retreat after the three days’ slaughter was finished. At Gettysburg his brigade was in the advance, opened the battle and, with the “Iron Brigade,” sustained the brunt of the fighting on the memorable 1st of July 1863. During that day. his old regiment, the Sixth, was attached to his brigade. Major-General Newton, in his report, details the part taken in this action as follows:

“General Cutler was in the advance and opened the battle of Gettsyburg. In this severe and obstinate engagement he held the right for four hours, changing front without confusion, three times, under a galling fire, and lost, in killed and wounded, three-fourths of his officers and men, having three of his staff wounded and all the horses killed. When the order was given to retire, he marched the remnant of his brigade off the field in perfect order and checked the advance of Ewell’s corps, which gave the artillery time to retire. In effecting this he lost heavily. His brigade was engaged on the night of the second and the morning of the third in repulsing the assaults of the Rebels on the right of our line.”

During Grant’s campaign of 1864, General Wadsworth was killed in the second day’s battle in the Wilderness. On his death the command of the division devolved on General Cutler, which he held thereafter all through the series of battles that followed, and during the siege of Petersburg, until August 21, when he was wounded in the face while repulsing an assault on the Weldon Railroad. On the 15th of September, wounded and in broken health, from his long and arduous service, he was, at his own request relieved from field duty, and ordered to New York, to take charge of the forwarding of troops from that State. Subsequently he was ordered to the command of the draft camp of rendezvous at Jackson, Mich., where he remained till the close of the Rebellion. He was appointed Brevet Major-General. the commission to date from his last fight on the Weldon Railroad, August 21. 1864, He resigned July 1, 1865,and returned to Milwaukee. With the excitement of active duty gone, his recuperative powers failed to restore his impaired health, and his earthly career ended July 30, 1866. The following orders were issued at Madison on the occasion of his death, by Gov. Fairchild, one of his companions in arms, and by the G.A.R.

State of Wisconsin, Executive Department,

Madison. July 31, 1866.Executive Order No. 7.

The people of Wisconsin will hear with deep regret the announcement of the death of Brevet Major-General Lysander Cutler. at Milwaukee, on Monday the 30th inst.General Cutler was among the most efficient and best beloved soldiers from this State. Distinguished for his services, covered with honorable scars, filled with years and glory, he goes to his grave deeply mourned by the entire people of a sorrowing State.

As a testimony of respect, the flag upon the State Capitol will be displayed at half mast, on Tuesday, 31st of July, inst.

By the Governor,

Charles Fairchild, Military Secretary.LUCIUS FAIRCHILD

Headquarters Post No. 1. G.A.R;

Madison, July 31, 1866.Special Order No. 1.

It is my painful duty to announce the death of one of Wisconsin’s most devoted and prominent general officers during the late war, Major-General Lysander Cutler, of Milwaukee.

It is ordered that as a mark of respect to the deceased, the members oi’ this post wear the badge of mourning prescribed by army regulations, for the period or ten days from this date.

By command of

Henry Sanford, P.A.J.W. TOLFORD, P.C.

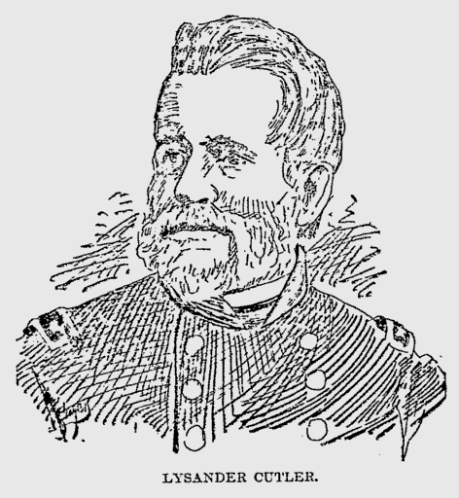

General Cutler was married in 1830, to Catherine W. Bassett. He had five children, two sons and three daughters, all of whom are still living. His widow still survives. In stature he was six feet tall and spare. His eyes were iron gray, deep set. and overhung by heavy eyebrows. He was prematurely gray, and during the later years of life both his hair and beard were white. His indomitable will and strict devotion to duty rendered him stern and uncompromising in his general bearing and appearance; but underneath his rough exterior beat a heart, as tender as a woman’s, that won the lasting love of all who came to know him well. To the toils, dangers and sufferings of his campaigns he never yielded, but on receiving the tidings of the death of his little grandson, who died while he was in the service, he took to his tent and bed, completely bowed and broken by the great grief that had smote his heart. The child and the grim old warrior now sleep side by side at Forest Home.

Gen. Lysander Cutler (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

“A real bona fide, unmitigated Irishman”

December 7, 2014

By Leo

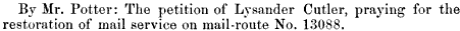

“The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things”, by Thomas Nast Published 2 September 1871 in Harper’s Weekly. Nast, who battled Tammany Hall and designed the modern image of Santa Claus, is one of the most famous American political cartoonists. However, he frequently depicted Irish-Americans as drunken, monkey-like monsters (Wikimedia Images).

It has been a while since I’ve posted anything new. My personal life has made it impossible to meet my former quota of three new posts a month. Now, it seems like I’ll be lucky to get one every three months. I haven’t forgotten about this site, however, and there is certainly no shortage of new topics. Unfortunately, most of them require more effort than I am able to give right now. Today, however, I have a short one.

Regular readers will know that the 1855 La Pointe annuity payment to the Lake Superior Chippewa bands is a frequent subject on Chequamegon History. To fully understand the context of this post, I recommend reading some of the earlier posts on that topic. The 1855 payment produced dozens of interesting stories and anecdotes: some funny, some tragic, some heroic, some bizarre, and many complicated. We’ve covered everything from Chief Buffalo’s death, to Hanging Cloud the female warrior, to Chief Blackbird’s great speech, to the random arrival of several politicians, celebrities, and dignitaries on Madeline Island.

Racism is an unavoidable subject in nearly all of these stories. The decisive implementation of American power on the Chequamegon Region in the 1850s cannot be understood without harshly examining the new racial order that it brought.

The earlier racial order (Native, Mix-blood, European) allowed Michel Cadotte Jr., being only of one-eighth European ancestry to be French while Antoine Gendron, of full French ancestry, was seen as fully Ojibwe. The new American order, however, increasingly defined ones race according to the shade of his or her skin.

But there are never any easy narratives in the history of this area, and much can be missed if the story of American domination is only understood as strictly an Indian/White conflict. There are always misfits, and this area was full of them.