Oshogay

August 12, 2013

At the most recent count, Chief Buffalo is mentioned in over two-thirds of the posts here on Chequamegon History. That’s the most of anyone listed so far in the People Index. While there are more Buffalo posts on the way, I also want to draw attention to some of the lesser known leaders of the La Pointe Band. So, look for upcoming posts about Dagwagaane (Tagwagane), Mizay, Blackbird, Waabojiig, Andeg-wiiyas, and others. I want to start, however, with Oshogay, the young speaker who traveled to Washington with Buffalo in 1852 only to die the next year before the treaty he was seeking could be negotiated.

I debated whether to do this post, since I don’t know a lot about Oshogay. I don’t know for sure what his name means, so I don’t know how to spell or pronounce it correctly (in the sources you see Oshogay, O-sho-ga, Osh-a-ga, Oshaga, Ozhoge, etc.). In fact, I don’t even know how many people he is. There were at least four men with that name among the Lake Superior Ojibwe between 1800 and 1860, so much like with the Great Chief Buffalo Picture Search, the key to getting Oshogay’s history right is dependent on separating his story from those who share his name.

In the end, I felt that challenge was worth a post in its own right, so here it is.

Getting Started

According to his gravestone, Oshogay was 51 when he died at La Pointe in 1853. That would put his birth around 1802. However, the Ojibwe did not track their birthdays in those days, so that should not be considered absolutely precise. He was considered a young man of the La Pointe Band at the time of his death. In my mind, the easiest way to sort out the information is going to be to lay it out chronologically. Here it goes:

1) Henry Schoolcraft, United States Indian Agent at Sault Ste. Marie, recorded the following on July 19, 1828:

Oshogay (the Osprey), solicited provisions to return home. This young man had been sent down to deliver a speech from his father, Kabamappa, of the river St. Croix, in which he regretted his inability to come in person. The father had first attracted my notice at the treaty of Prairie du Chien, and afterwards received a small medal, by my recommendation, from the Commissioners at Fond du Lac. He appeared to consider himself under obligations to renew the assurance of his friendship, and this, with the hope of receiving some presents, appeared to constitute the object of his son’s mission, who conducted himself with more modesty and timidity before me than prudence afterwards; for, by extending his visit to Drummond Island, where both he and his father were unknown, he got nothing, and forfeited the right to claim anything for himself on his return here.

I sent, however, in his charge, a present of goods of small amount, to be delivered to his father, who has not countenanced his foreign visit.

Oshogay is a “young man.” A birth year of 1802 would make him 26. He is part of Gaa-bimabi’s (Kabamappa’s) village in the upper St. Croix country.

2) In June of 1834, Edmund Ely and W. T. Boutwell, two missionaries, traveled from Fond du Lac (today’s Fond du Lac Reservation near Cloquet) down the St. Croix to Yellow Lake (near today’s Webster, WI) to meet with other missionaries. As they left Gaa-bimabi’s (Kabamappa’s) village near the head of the St. Croix and reached the Namekagon River on June 28th, they were looking for someone to guide them the rest of the way. An old Ojibwe man, who Boutwell had met before at La Pointe, and his son offered to help. The man fed the missionaries fish and hunted for them while they camped a full day at the mouth of the Namekagon since the 29th was a Sunday and they refused to travel on the Sabbath. On Monday the 30th, the reembarked, and Ely recorded in his journal:

The man, whose name is “Ozhoge,” and his son embarked with us about 1/2 past 9 °clk a.m. The old man in the bow and myself steering. We run the rapids safely. At half past one P. M. arrived at the mouth of Yellow River…

Ozhoge is an “old man” in 1834, so he couldn’t have been born in 1802. He is staying on the Namekagon River in the upper St. Croix country between Gaa-bimabi and the Yellow Lake Band. He had recently spent time at La Pointe.

3) Ely’s stay on the St. Croix that summer was brief. He was stationed at Fond du Lac until he eventually wore out his welcome there. In the 1840s, he would be stationed at Pokegama, lower on the St. Croix. During these years, he makes multiple references to a man named Ozhogens (a diminutive of Ozhoge). Ozhogens is always found above Yellow River on the upper St. Croix.

Ozhogens has a name that may imply someone older (possibly a father or other relative) lives nearby with the name Ozhoge. He seems to live in the upper St. Croix country. A birth year of 1802 would put him in his forties, which is plausible.

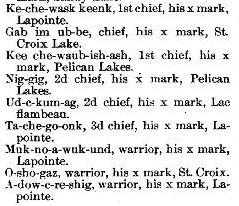

Ke-che-wask keenk (Gichi-weshki) is Chief Buffalo. Gab-im-ub-be (Gaa-bimabi) was the chief Schoolcraft identified as the father of Oshogay. Ja-che-go-onk was a son of Chief Buffalo.

4) On August 2, 1847, the United States and the Mississippi and Lake Superior Ojibwe concluded a treaty at Fond du Lac. The US Government wanted Ojibwe land along the nation’s border with the Dakota Sioux, so it could remove the Ho-Chunk people from Wisconsin to Minnesota.

Among the signatures, we find O-sho-gaz, a warrior from St. Croix. This would seem to be the Ozhogens we meet in Ely.

Here O-sho-gaz is clearly identified as being from St. Croix. His identification as a warrior would probably indicate that he is a relatively young man. The fact that his signature is squeezed in the middle of the names of members of the La Pointe Band may or may not be significant. The signatures on the 1847 Treaty are not officially grouped by band, but they tend to cluster as such.

5) In 1848 and 1849 George P. Warren operated the fur post at Chippewa Falls and kept a log that has been transcribed and digitized by the University of Wisconsin Eau Claire. He makes several transactions with a man named Oshogay, and at one point seems to have him employed in his business. His age isn’t indicated, but the amount of furs he brings in suggests that he is the head of a small band or large family. There were multiple Ojibwe villages on the Chippewa River at that time, including at Rice Lake and Lake Shatac (Chetek). The United States Government treated with them as satellite villages of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band.

Based on where he lives, this Oshogay might not be the same person as the one described above.

6) In December 1850, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in the case Oshoga vs. The State of Wisconsin, that there were a number of irregularities in the trial that convicted “Oshoga, an Indian of the Chippewa Nation” of murder. The court reversed the decision of the St. Croix County circuit court. I’ve found surprisingly little about this case, though that part of Wisconsin was growing very violent in the 1840s as white lumbermen and liquor salesmen were flooding the country.

Pg 56 of Containing cases decided from the December term, 1850, until the organization of the separate Supreme Court in 1853: Volume 3 of Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Wisconsin: With Tables of the Cases and Principal Matters, and the Rules of the Several Courts in Force Since 1838, Wisconsin. Supreme Court Authors: Wisconsin. Supreme Court, Silas Uriah Pinney (Google Books).

The man killed, Alexander Livingston, was a liquor dealer himself.

Alexander Livingston, a man who in youth had had excellent advantages, became himself a dealer in whisky, at the mouth of Wolf creek, in a drunken melee in his own store was shot and killed by Robido, a half-breed. Robido was arrested but managed to escape justice.

~From Fifty Years in the Northwest by W.H.C Folsom

Several pages later, Folsom writes:

At the mouth of Wolf creek, in the extreme northwestern section of this town, J. R. Brown had a trading house in the ’30s, and Louis Roberts in the ’40s. At this place Alex. Livingston, another trader, was killed by Indians in 1849. Livingston had built him a comfortable home, which he made a stopping place for the weary traveler, whom he fed on wild rice, maple sugar, venison, bear meat, muskrats, wild fowl and flour bread, all decently prepared by his Indian wife. Mr. Livingston was killed by an Indian in 1849.

Folsom makes no mention of Oshoga, and I haven’t found anything else on what happened to him or Robido (Robideaux?).

It’s hard to say if this Oshoga is the Ozhogen’s of Ely’s journals or the Oshogay of Warren’s. Wolf Creek is on the St. Croix, but it’s not far from the Chippewa River country either, and the Oshogay of Warren seems to have covered a lot of ground in the fur trade. Warren’s journal, linked in #4, contains a similar story of a killing and “frontier justice” leading to lynch mobs against the Ojibwe. To escape the violence and overcrowding, many Ojibwe from that part of the country started to relocate to Fond du Lac, Lac Courte Oreilles, or La Pointe/Bad River. La Pointe is also where we find the next mention of Oshogay.

7) From 1851 to 1853, a new voice emerged loudly from the La Pointe Band in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy. It was that of Buffalo’s speaker Oshogay (or O-sho-ga), and he spoke out strongly against Indian Agent John Watrous’ handling of the Sandy Lake payments (see this post) and against Watrous’ continued demands for removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. There are a number of documents with Oshogay’s name on them, and I won’t mention all of them, but I recommend Theresa Schenck’s William W. Warren and Howard Paap’s Red Cliff, Wisconsin as two places to get started.

Chief Buffalo was known as a great speaker, but he was nearing the end of his life, and it was the younger chief who was speaking on behalf of the band more and more. Oshogay represented Buffalo in St. Paul, co-wrote a number of letters with him, and most famously, did most of the talking when the two chiefs went to Washington D.C. in the spring of 1852 (at least according to Benjamin Armstrong’s memoir). A number of secondary sources suggest that Oshogay was Buffalo’s son or son-in-law, but I’ve yet to see these claims backed up with an original document. However, all the documents that identify by band, say this Oshogay was from La Pointe.

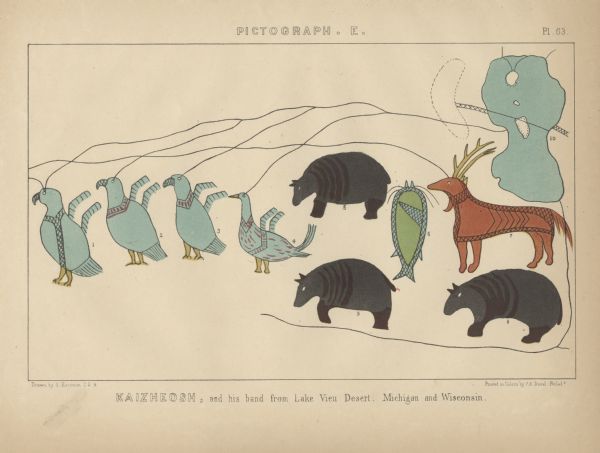

The Wisconsin Historical Society has digitized four petitions drafted in the fall of 1851 and winter of 1852. The petitions are from several chiefs, mostly of the La Pointe and Lac Courte Oreilles/Chippewa River bands, calling for the removal of John Watrous as Indian Agent. The content of the petitions deserves its own post, so for now we’ll only look at the signatures.

November 6, 1851 Letter from 30 chiefs and headmen to Luke Lea, Commissioner of Indian Affairs: Multiple villages are represented here, roughly grouped by band. Kijiueshki (Buffalo), Jejigwaig (Buffalo’s son), Kishhitauag (“Cut Ear” also associated with the Ontonagon Band), Misai (“Lawyerfish”), Oshkinaue (“Youth”), Aitauigizhik (“Each Side of the Sky”), Medueguon, and Makudeuakuat (“Black Cloud”) are all known members of the La Pointe Band. Before the 1850s, Kabemabe (Gaa-bimabi) and Ozhoge were associated with the villages of the Upper St. Croix.

November 8, 1851, Letter from the Chiefs and Headmen of Chippeway River, Lac Coutereille, Puk-wa-none, Long Lake, and Lac Shatac to Alexander Ramsey, Superintendent of Indian Affairs: This letter was written from Sandy Lake two days after the one above it was written from La Pointe. O-sho-gay the warrior from Lac Shatac (Lake Chetek) can’t be the same person as Ozhoge the chief unless he had some kind of airplane or helicopter back in 1851.

Undated (Jan. 1852?) petition to “Our Great Father”: This Oshoga is clearly the one from Lake Chetek (Chippewa River).

Undated (Jan. 1852?) petition: These men are all associated with the La Pointe Band. Osho-gay is their Speaker.

In the early 1850s, we clearly have two different men named Oshogay involved in the politics of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. One is a young warrior from the Chippewa River country, and the other is a rising leader among the La Pointe Band.

Washington Delegation July 22, 1852 This engraving of the 1852 delegation led by Buffalo and Oshogay appeared in Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians. Look for an upcoming post dedicated to this image.

8) In the winter of 1853-1854, a smallpox epidemic ripped through La Pointe and claimed the lives of a number of its residents including that of Oshogay. It had appeared that Buffalo was grooming him to take over leadership of the La Pointe Band, but his tragic death left a leadership vacuum after the establishment of reservations and the death of Buffalo in 1855.

Oshogay’s death is marked in a number of sources including the gravestone at the top of this post. The following account comes from Richard E. Morse, an observer of the 1855 annuity payments at La Pointe:

The Chippewas, during the past few years, have suffered extensively, and many of them died, with the small pox. Chief O-SHO-GA died of this disease in 1854. The Agent caused a suitable tomb-stone to be erected at his grave, in La Pointe. He was a young chief, of rare promise and merit; he also stood high in the affections of his people.

Later, Morse records a speech by Ja-be-ge-zhick or “Hole in the Sky,” a young Ojibwe man from the Bad River Mission who had converted to Christianity and dressed in “American style.” Jabegezhick speaks out strongly to the American officials against the assembled chiefs:

…I am glad you have seen us, and have seen the folly of our chiefs; it may give you a general idea of their transactions. By the papers you have made out for the chiefs to sign, you can judge of their ability to do business for us. We had but one man among us, capable of doing business for the Chippewa nation; that man was O-SHO-GA, now dead and our nation now mourns. (O-SHO-GA was a young chief of great merit and much promise; he died of small-pox, February 1854). Since his death, we have lost all our faith in the balance of our chiefs…

This O-sho-ga is the young chief, associated with the La Pointe Band, who went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852.

9) In 1878, “Old Oshaga” received three dollars for a lynx bounty in Chippewa County.

Report of the Wisconsin Office of the Secretary of State, 1878; pg. 94 (Google Books)

It seems quite possible that Old Oshaga is the young man that worked with George Warren in the 1840s and the warrior from Lake Chetek who signed the petitions against Agent Watrous in the 1850s.

10) In 1880, a delegation of Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, and Lac du Flambeau chiefs visited Washington D.C. I will get into their purpose in a future post, but for now, I will mention that the chiefs were older men who would have been around in the 1840s and ’50s. One of them is named Oshogay. The challenge is figuring out which one.

Ojibwe Delegation c. 1880 by Charles M. Bell. [Identifying information from the Smithsonian] Studio portrait of Anishinaabe Delegation posed in front of a backdrop. Sitting, left to right: Edawigijig; Kis-ki-ta-wag; Wadwaiasoug (on floor); Akewainzee (center); Oshawashkogijig; Nijogijig; Oshoga. Back row (order unknown); Wasigwanabi; Ogimagijig; and four unidentified men (possibly Frank Briggs, top center, and Benjamin Green Armstrong, top right). The men wear European-style suit jackets and pants; one man wears a peace medal, some wear beaded sashes or bags or hold pipes and other props.(Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian).

- Upper row reading from the left.

- 1. Vincent Conyer- Interpreter 1,2,4,5 ?, includes Wasigwanabi and Ogimagijig

- 2. Vincent Roy Jr.

- 3. Dr. I. L. Mahan, Indian Agent Frank Briggs

- 4. No Name Given

- 5. Geo P. Warren (Born at LaPointe- civil war vet.

- 6. Thad Thayer Benjamin Armstrong

- Lower row

- 1. Messenger Edawigijig

- 2. Na-ga-nab (head chief of all Chippewas) Kis-ki-ta-wag

- 3. Moses White, father of Jim White Waswaisoug

- 4. No Name Given Akewainzee

- 5. Osho’gay- head speaker Oshawashkogijig or Oshoga

- 6. Bay’-qua-as’ (head chief of La Corrd Oreilles, 7 ft. tall) Nijogijig or Oshawashkogijig

- 7. No name given Oshoga or Nijogijig

The Smithsonian lists Oshoga last, so that would mean he is the man sitting in the chair at the far right. However, it doesn’t specify who the man seated on the right on the floor is, so it’s also possible that he’s their Oshoga. If the latter is true, that’s also who the unknown writer of the library caption identified as Osho’gay. Whoever he is in the picture, it seems very possible that this is the same man as “Old Oshaga” from number 9.

11) There is one more document I’d like to include, although it doesn’t mention any of the people we’ve discussed so far, it may be of interest to someone reading this post. It mentions a man named Oshogay who was born before 1860 (albeit not long before).

For decades after 1854, many of the Lake Superior Ojibwe continued to live off of the reservations created in the Treaty of La Pointe. This was especially true in the St. Croix region where no reservation was created at all. In the 1910s, the Government set out to document where various Ojibwe families were living and what tribal rights they had. This process led to the creation of the St. Croix and Mole Lake reservations. In 1915, we find 64-year-old Oshogay and his family living in Randall, Wisconsin which may suggest a connection to the St. Croix Oshogays. As with number 6 above, this creates some ambiguity because he is listed as enrolled at Lac Courte Oreilles, which implies a connection to the Chippewa River Oshogay. For now, I leave this investigation up to someone else, but I’ll leave it here for interest.

United States. Congress. House. Committee on Indian Affairs. Indian Appropriation Bill: Supplemental Hearings Before a Subcommittee. 1919 (Google Books).

This is not any of the Oshogays discussed so far, but it could be a relative of any or all of them.

In the final analysis

These eleven documents mention at least four men named Oshogay living in northern Wisconsin between 1800 and 1860. Edmund Ely met an old man named Oshogay in 1834. He is one. A 64-year old man, a child in the 1850s, was listed on the roster of “St. Croix Indians.” He is another. I believe the warrior from Lake Chetek who traded with George Warren in the 1840s could be one of the chiefs who went to Washington in 1880. He may also be the one who was falsely accused of killing Alexander Livingston. Of these three men, none are the Oshogay who went to Washington with Buffalo in 1852.

That leaves us with the last mystery. Is Ozhogens, the young son of the St. Croix chief Gaa-bimabi, the orator from La Pointe who played such a prominent role in the politics of the early 1850s? I don’t have a smoking gun, but I feel the circumstantial evidence strongly suggests he is. If that’s the case, it explains why those who’ve looked for his early history in the La Pointe Band have come up empty.

However, important questions remain unanswered. What was his connection to Buffalo? If he was from St. Croix, how was he able to gain such a prominent role in the La Pointe Band, and why did he relocate to La Pointe anyway? I have my suspicions for each of these questions, but no solid evidence. If you do, please let me know, and we’ll continue to shed light on this underappreciated Ojibwe leader.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benj G., and Thomas P. Wentworth. Early Life among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong : Treaties of 1835, 1837, 1842 and 1854 : Habits and Customs of the Red Men of the Forest : Incidents, Biographical Sketches, Battles, &c. Ashland, WI: Press of A.W. Bowron, 1892. Print.

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Folsom, William H. C., and E. E. Edwards. Fifty Years in the Northwest. St. Paul: Pioneer, 1888. Print.

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 12 August 2013. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1995. Print.

Paap, Howard D. Red Cliff, Wisconsin: A History of an Ojibwe Community. St. Cloud, MN: North Star, 2013. Print.

Redix, Erik M. “The Murder of Joe White: Ojibwe Leadership and Colonialism in Wisconsin.” Diss. University of Minnesota, 2012. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. The Voice of the Crane Echoes Afar: The Sociopolitical Organization of the Lake Superior Ojibwa, 1640-1855. New York: Garland Pub., 1997. Print.

———–William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers: With Brief Notices of Passing Events, Facts, and Opinions, A.D. 1812 to A.D. 1842. Philadelphia, [Pa.: Lippincott, Grambo and, 1851. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Who doesn’t love a good mystery?

In my continuing goal to actually add original archival research to this site, rather than always mooching off the labors of others, I present to you another document from the Wheeler Family Papers. Last week, I popped over to the Wisconsin Historical Society collections at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center in Ashland, and brought back some great stuff. Unlike the somber Sandy Lake letters I published July 11th, this first new document is a mysterious (and often hilarious) journal from 1843 and 1844.

It was in the Wheeler papers, but it was neither written by nor for one of the Wheelers. There is no name on it to indicate an author, and despite a year of entries, very little to indicate his occupation (unless he was a weatherman). He starts in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, bound for Fond du Lac, Minnesota–though neither was a state yet. Our guy reaches Lake Superior at a time of great change. The Ojibwe have just ceded the land in the Treaty of 1842, commercial traffic is beginning to start on Lake Superior, and the old fur-trade economy is dying out.

Our guy doesn’t seem to be a native of this area. He’s not married. He doesn’t seem to be strongly connected to the fur trade. If he works for the government, he isn’t very powerful. He is definitely not a missionary. He doesn’t seem to be a land speculator or anything like that.

Who is he, and why did he come here? I have some hunches, but nothing solid. Read it and let me know what you think.

1843

Aug. 24th 1843. left Taycheedah for Milwaukie on my route to Lake Superior, drove to Cases[?] in Fond du Lac

25th Drove to Cases on Milwaukie road, commenced rowing before we arrived, and we put up for the night.

26th Started in the rain, drove to Vinydans[?], rain all the time. wet my carpet bag and clothes—we put out 12 O’clock m. took clothes out of my traveling bag and dried them.

27th sunday Left early in the morning. arrived at Milwaukie at 12 O clock M. stayed at the Fountain house, had good fun.

Arch Rock, Mackinac Island (Jeffness upload to Wikimedia Commons CC)

28th Purchased provisions and other articles of outfit and embarked aboard the Steamboat Chesapeake for Mackinac 9 O’clock P. M. had a pleasant time.

30th Arrived at Mackinac 6 O’clock A.M. put up at Mr. Wescott’s had excellent fare and good company, charges reasonable. four Thousand Indian men encamped on the Island for Payment—very warm weather—Slept with windows raised, and uncomfortably warm. There are a few white families, but the mass of the people are a motley crowd “from snowy white to sooty[?],” I visited the curiosities, the old fort Holmes, the sugar loaf rock the arched rock—heard some good stories well told by Mr. Wescott and a gentleman from Philadelphia.

Sept 4th Left Mackinac on board the Steamer Gen. Scott 8 O’clock A. M. arrived at Sault St, Marie same night 6 O’clock—very pleasant weather. gardens look well. Put up at Johnsons. had good fare fish eggs fowls and garden vegetables.

7th Embarked on board the Brig John Jacob Astor for La Pointe. Sailed fifty miles. at midnight the wind shifted suddenly into the N.W. and blew a hurricane and we were obliged to run back into the St. Marie’s river, and lay there at Pine Point until Sunday.

10th when we best[?] out of the river, and proceeding on

1843

Sept 11th Monday heading against hard wind all day—

makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Photo: Smithsonian Institution; Definition: Ojibwe People’s Dictionary).

makak: a semi-rigid or rigid container: a basket (especially one of birch bark), a box (Photo: Smithsonian Institution; Definition: Ojibwe People’s Dictionary).12th Warm cloudless brilliant morning, a perfect calm—10 O’clock fair wind, and with every sail our vessel plows the deep, with majesty.

13th cloudy—fair wind, we arrive at La Pointe 9 O’clock P.M. when a cannon fired from on board the vessel announced our arrival.

Mr. Wheeler of the Presbyterian Mission was very kind in receiving me to room with him, and I am indebted to him and family for many acts of kindness during my stay at La Pointe, and I fell under [?] for about 15 lbs boiled beef and a small Mokuk of sugar, which they insisted on my taking on my departure for Fond du Lac, and which men[?] very p[?]able while wind on my way upon the shore of Lake Superior.

27th Left La Pointe about 4 O clock P. M. in small boat in company with the farmer & Blacksmith stationed at Fond du Lac. we rowed to Raspberry river and encamped.

28th Head wind—rowed to Siscowet Bay and encamped.

29th Rain and fair wind, we embarked about 8 O clock in the rain—in doubling Bark Point we got an Ocean more, but our little boat rides it nobly. the wind and rain increase, and we run into Pukwaekah river, the wind blowing directly on shore and the waves dashing to an enormous height, it was by miracle, our men chose, that struck the mouth of that small river, and entered in safety, After we had pitched our tent, we saw eight canoes with sails making directly for the river. they could not strike the entrance at the mouth of the river, and were driven on shore upon the beach and filled. We assisted in hauling our some of the first that came, and they assisted the rest.

1843

Sept 30th High wind and rain. We remained at this place until wednesday.

Oct 4th At 1 O clock A. M. the wind having abated we again embarked and rowed into the mouth of the St. Louis at 1 O clock P. M. I threw myself upon the bank, completely exhausted, and thankful to be once more on Terra firma, and determined to stay there until my strength should be reignited, however having taken dinner upon the bank and a cup of tea, the wind sprang up favorably and we sailed up the river ten miles and encamped upon an island.

5th Arrived at the A.M.F.’s Trading Post the place of our destination, at 10 O’clock A.M. (mild and pleasant from this time to the 24th weather has been remarkably.

24th Cold—snow and some ice in the river

26th The river froze over at this place.

27th Colder the ice makes fast in the river

Nov 1st Crossed the river on the ice—winter weather—

2nd Moderate

5th Sunday warm the ice is failing in the river dangerous crossing on foot

7th and 8th Warm and pleasant—the ice is melting

9th Warm and misty—thawing fort

20th Warm—rains a little—the river is nearly clean of ice—

Dec. 3rd The weather up to this date has been very mild. No snow, the ice on the river scarcely sufficient to bear a horse and train—

Jan 1st 1844 Warm and misty—more like April fool than New years day

1844

Jan 1st On this day I must record the honor of being visited by some half dozen pretty squaws expecting a New Years present and a kiss, not being aware of the etiquette of the place, we were rather taken by surprise, in not having presents prepared—however a few articles were mustered, an I must here acknowledge that although, out presents were not very valuable, we were entitled to the reward of a kiss, which I was ungallant enough not to claim, but they’ll never slip through my fingers in that way again.

March 2nd New sugar, weather pleasant

3rd Cloudy chilly wind

Bebiizigindibe (Curly Head) signed the Treaty of 1842 as 2nd Chief from Gull Lake. According to William Warren, he was known as “Little Curly Head.” “Big Curly Head” was a famous Gull Lake war chief who died in 1825 while returning home from the Treaty of Prairie du Chien. The younger chief was the son of Niigaani-giizhig (also killed by the Dakota), and the half-brother of Gwiiwizhenzhish or Bad Boy (pictured). According to Warren, this incident broke a truce between the two nations (Photo by Whitney’s of St. Paul, Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society).

17th Pleasant, two Indians arrive and bring the news that the chief of the Gull Lake band of Chippeways has been killed by the Sioux—there appears to be not much excitement among the Indians here upon the subject. The name of the chief that is killed is Babezegondeba (Curly Head)

The winter has been remarkably mild and pleasant—but little snow—no tedious storms and but two or three cold days.

31st A cloudy brilliant day—The frogs are singing

April 1st A lovely spring morning—warm—the Ducks are flying

Afternoon a little cloudy but warm

Evening, moonlight—beautiful and bright

2nd Warm morning. afternoon high wind rain

A pleasant moonlight evening—warm

3rd Briliant morning—warm afternoon appearance of rain. the ice is moving out of the river Ducks & Geese are flying and we have fresh fish

4th Clean cold morning wind N.E. afternoon high wind chilly. The clear of ice at this place.

5th Cold cloudy morning. Wind NE. After noon wind and rain from the N.E.

1844

April

6th Wind N.E. continues to rain moderately again—thunder and rain during the past night.

7th Sunday. warm rainy day—attended church

8th Cloudy morning and warm, afternoon very fair.

9th Fair frosty morning, afternoon very warm.

10th Cloudy and warm—thunder lightning and rain during the past night, afternoon fair and warm.

11th Rainy warm morning, with thunder and lightning afternoon fair and very warm.

12th Fair warm morning, after noon, cloudy with a little rain thunder and lightning—Musketoes appear

13th Most beautiful spring morning—fair warm day, wind S.W.

14th Cool cloudy day—Wind N.E. (Sunday)

15th Rainy, warm day

16th Fair cool morning—after noon warmer

17th Fair and warm day (Striker started for La Pointe Bellanger with the Blacksmith)

18th Another beautiful day.

19th Warm rainy day

20th Rainy day

21st Sunday fair and cool—high wind from N.E.

22nd Cool morning—some cloudy—P.M. high wind and rain

23rd High wind and rain from the N.E.—tremendous storm;

24th Fair morning moderately warm—afternoon fair. Musketoes

25th Rainy day

26th Cool cloudy morning

27th} fair & warm

28th

29th Beautiful April day

30th Rainy day

May 1st Warm with high wind

2nd Do. a little rain

3rd Warm—sunshine and showers

4th} Beautiful warm day

5th

6th Most beautiful brilliant day

the woods have already a shade of green

1844

May 7th Warm rainy day

June 21st Since the last date the weather has been good for the season—during the month of may occasionally a frosty night with sufficient variety of sunshine and shower. On this day I started for La Pointe in company with the farmer, the Blacksmith & Striker, and Indian, named Red Bird, in a small boat. we rowed to the River Aminicon and encamped.

22nd Three O’clock A.M. Struck our tent and embarked—took the oars, (about 6 O’clock met a large batteau from La Pointe Bound for Fond du Lac with seed Potatoes for the Indians, it also had letters for Fond du Lac, among which was one for my self—The farmer returned to Fond du Lac to attend to the distribution of the Potatoes. We breakfasted at Burnt wood River. about 7 O’clock The wind sprang up favorably and blew a steady strong blast all day, and we arrived at La Pointe about sun set.

23rd Sunday, attended church

24th Did nothing in particular—weather very warm

28th Was taken suddenly with crick in the back which laid me up for a week

July 4th Independence day—Just able to get about The batteaus were fitted out by Dr. Borup for a pleasure ride, by way of celebrating the birth day of American Independence—These boats were propelled by eight sturdy Canadian voyagers each, nearly all the inhabitants of La Pointe were on board, and I was among the number, we were conveyed , amidst the firing of pocket pistols, rifles, shot guns & the music and mirth of the half-breeds and the mild cadence of the Canadian Boat songs, to one of the Islands of the Apostles about ten miles distant from La Pointe. Here we disembarked and partook of a sumptuous dinner which had been prepared and brought on board the boats.

The brig John Jacob Astor, named for the fur baron pictured above, was one of the earliest commercial vessels on Lake Superior. It sank near Copper Harbor about two months after the La Pointe Independence Day celebration (Painting by Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Images).

Just as we had finished the repast, having done ample justice to the viands which were placed before us, Some one, by means of a large spy glass discovered the Brig Astor supposed to be about 10 or 15 miles distant beating for La Pointe in thirty minutes we were all on board our boats and bound to meet the Astor. The Canadians were all commotion, and rowed and sung with all their might for about eight miles when finding that we yet a long distance from the vessel, she making little head way, and it being past middle of the afternoon, the question arose whether we should go forward or return to La Pointe. a vote was taken, but as the chairman was unable to decide which party carried the point, he said he should be under the necessity of dividing the boat. this was accordingly done, and all those who were desirous to go a head, took one boat, and those who wished to return the other. I was anxious to go and meet the vessel, but being unwell was advised to return, and did so, and arrived at La Pointe at dusk.

July 11th Started from La Pointe for Fond du Lac with Mr. Johnson & Lady missionaries at Leech Lake. Mr. Hunter the Blacksmith, and two Indians, in our small boat. sailed about three miles a squall came up suddenly and drove us back to La Pointe—Started again after noon and rowed to Sandy River and encamped next

12th day rowed to Burnt wood (Iron) river.

13th Arrived at Fond du Lac 9 O’clock P.M.

Aug 6th Since I arrived the weather has been intensely warm Yesterday Mr. Hunter started for La Pointe to attend the Payment. I am alone

Erethizon dorsatum, North American Porcupine: I’m going to assume our author devoured one of these guys. Hedgehogs are exclusively an Old World animal (J. Glover, Wikimedia Images, CC)

Aug 27th The weather fair, the nights begin to be cooler. Musketoes and gnats have given up the contest and left us in full and peaceable possession of the country. Since Mr. hunter left for the payment I have been unwell, no appetite, foul stomac, after trying various remedies, in order to settle my stomac, I succeeded in effecting it at last by devouring a large portion of roast Hedge hog But was immediately taken down with a rheumatism in my back, which has held me to the present time and from which I am just recovering.

An Indian has just arrived from Leech Lake bringing news that the Sioux have killed a chippeway and that the Chippeways in retaliation have killed eight Sioux.

29th Johnson arrived from La Pointe—Rainy day.

31st The farmer and Blacksmith arrived from La Pointe

The weather is very warm—

Sept 5 Weather continues warm. Mr. Wright Mr Coe and wife start for Red Lake (they are Missionaries)

10 Frosty night

11 Do. “

12 Cloudy and warm

13 Do. Do. “

14 Do. Do. Do. Batteau arrived from La Pointe

15 Sunday foggy morning—very warm fair day

16 Warm

22 Do.

29 fair

Oct 3rd Warm and fair

Sunday 13th fair days & frosty nights, this month, thus far

14-15 Rainy days

19th cold

20 Snow covers the ground—the river is nightly frozen over at some places—

21 fine day

22&23 fair & warm thunder & lightning at night

24th Do. Do. (Agent arrived from La Pointe 28th)

28th Cold—snow in the afternoon and night

—————————————————————————————————————–

END OF 1843-44 JOURNAL

The last two pages of the document are written in the same handwriting, a few years later in 1847, and take the form of a cash ledger.

________________________________________________________________

| 1847 | Madam Defoe [?][?] 1847 | ||||

| Dec 3rd | [?] | [?] | |||

| p/o 4 lbs Butter | 1 | 00 | |||

| “ | “ 3 Gallons Soap | 1 | 00 | ||

| 15th | By Making 2 pr Moccasins | 50 | |||

| “ | [Washing 2 Down pieces ?] | 1 | 00 | ||

| “ | Mending pants [?] | 25 | |||

| Joseph Defoe Jr | |||||

| p/o 50 lbs Candles | 1 | 50 | |||

| “ 10 “ Pork | 1 | 50 | |||

| “ 20 “ flour | 1 | 25 | |||

| By three days work by self and son | 3 | 75 | |||

| p/o Pork 4 lbs | 50 | ||||

____________________________________________________________________________

| 1847 | Memorandum | ||||

| Aug | Went to La Pointe with Carleton | ||||

| Staid four days | |||||

| Oct 9th | Went to La Pointe (Monday) | ||||

| 12 | Returned 4 O’clock P.M. | ||||

| 16 | Went to La Pointe. returned same night | ||||

| 24th | Do. Do. | ||||

| 25th | Returned | ||||

| Nov. 28th | Lent Mr. Wood 10 lbs nails– | ||||

| 5 lbs 4[?] 5 lbs 10[?] previous to this time 12 lbs | |||||

| 4[?] Total= 22 lbs | |||||

| By three days work by self and son | |||||

| p/o Pork 4 lbs | |||||

| Nov | T.A. Warren Due to Cash | 2 | 00 | ||

Truman A. Warren, son of Lyman Warren and Marie Cadotte Warren, brother of Willam W. (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: 28289)

Truman A. Warren, son of Lyman Warren and Marie Cadotte Warren, brother of Willam W. (Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID: 28289)____________________________________________________________________________

While not overly significant historically, I enjoyed typing up this anonymous journal. The New Years, Independence Day, and “Hedge Hog” stories made me laugh out loud. You just don’t get that kind of stuff from an uptight missionary, greedy trader, or boring government official. It really makes me want to know who this guy was. If you can identify him, please let me know.

Sources:

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES. Ed. Charles J. Kappler. Oklahoma State University Library, n.d. Web. 21 June 2012. <http:// digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/>.

Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1995. Print.

Schenck, Theresa M. William W. Warren: The Life, Letters, and times of an Ojibwe Leader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007. Print.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1853. Print.

Warren, William W., and Edward D. Neill. History of the Ojibway Nation. Minneapolis: Ross & Haines, 1957. Print.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009. Print.

Fun With Maps

June 28, 2013

I’m someone who loves a good historical map, so one of my favorite websites is memory.loc.gov, the digital collections of the Library of Congress. You can spend hours zooming in on neat vintage maps. This post has snippets from eleven of them, stretching from 1674 to 1843. They are full of cool old inaccuracies, but they also highlight important historical trends and eras in our history. This should not be considered an exhaustive survey of the best maps out there, nor is it representative of all the LOC maps. Really, it’s just 11 semi-random maps with my observations on what I found interesting. Click on any map to go to the Library of Congress site where you can browse more of it. Enjoy:

French 1674

Nouvelle decouverte de plusieurs nations dans la Nouvelle France en l’année 1673 et 1674 by Louis Joliet. Joliet famously traveled from the Great Lakes down the Mississippi with the Jesuit Jacques Marquette in 1673.

- Cool trees.

- Baye des Puans: The French called the Ho-Chunk Puans, “Stinky People.” That was a translation of the Ojibwe word Wiinibiigoo (Winnebago), which means “stinky water people.” Green Bay is “green” in summer because of the stinky green algae that covers it. It’s not surprising that the Ho-Chunk no longer wish to be called the Winnebago or Puans.

- 8tagami: The French used 8 in Indian words for the English sound “W.” 8tagami (Odagami) is the Ojibwe/Odawa/Potawatomi word for the Meskwaki (Fox) People.

- Nations du Nord: To the French, the country between Lake Superior and Hudson Bay was the home of “an infinity of nations,” (check out this book by that title) small bands speaking dialects of Ojibwe, Cree, and Assiniboine Sioux.

- The Keweenaw is pretty small, but Lake Superior has generally the right shape.

French 1688

Carte de l’Amerique Septentrionnale by Jean Baptiste Louis Franquelin: Franquelin created dozens of maps as the royal cartographer and hydrographer of New France.

- Lake Superior is remarkably accurate for this time period.

- Nations sous le nom d’Outouacs: “Nations under the name of Ottawas”–the French had a tendency to lump all Anishinaabe peoples in the west (Ojibwe, Ottawa, Potawatomi, etc.) under the name Outouais or Outouacs.

- River names, some are the same and some have changed. Bois Brule (Brule River) in French is “burnt wood” a translation of the Ojibwe wiisakode. I see ouatsicoto inside the name of the Brule on this map (Neouatsicoton), but I’m not 100% sure that’s wiisakode. Piouabic (biwaabik is Ojibwe word for Iron) for the Iron River is still around. Mosquesisipi (Mashkiziibi) or Swampy River is the Ojibwe for the Bad River.

- Madeline Island is Ile. St. Michel, showing that it was known at “Michael’s Island” a century before Michel Cadotte established his fur post.

- Ance Chagoüamigon: Point Chequamegon

French 1703

Carte de la riviere Longue : et de quelques autres, qui se dechargent dans le grand fleuve de Missisipi [sic] … by Louis Armand the Baron de Lahontan. Baron Lahontan was a military officer of New France who explored the Mississippi and Missouri River valleys.

- Lake Superior looks quite strange.

- “Sauteurs” and Jesuits at Sault Ste. Marie: the French called the Anishinaabe people at Sault Ste. Marie (mostly Crane Clan) the Sauteurs or Saulteaux, meaning “people of the falls.” This term came to encompass most of the people who would now be called Ojibwe.

- Fort Dulhut: This is not Duluth, Minnesota, but rather Kaministiquia (modern-day Thunder Bay). It is named for the same person–Daniel Greysolon, the Sieur du Lhut (Duluth).

- Riviere Du Tombeau: “The River of Tombs” at the west end of the Lake is the St. Croix River, which does not actually flow into Lake Superior but connects it to the Mississippi over a short portage from the Brule River.

- Chagouamigon (Chequamegon) is placed much too far to the east.

- The Fox River is gigantic flowing due east rather than north into Green Bay. We see the “Savage friends of the French:” Outagamis (Meskwaki/Fox), Malumins (Menominee), and Kikapous (Kickapoo).

French 1742

Carte des lacs du Canada by Jacques N. Bellin 1742. Bellin was a famous European mapmaker who compiled various maps together. The top map is a detail from the Carte de Lacs. The bottom one is from a slightly later map.

- Of the maps shown so far, this has the best depiction of Chequamegon, but Lake Superior as a whole is much less accurate than on Franquelin’s map from fifty years earlier.

- The mysterious “Isle Phillipeaux,” a second large island southeast of Isle Royale shows prominently on this map. Isle Phillipeaux is one of those cartographic oddities that pops up on maps for decades after it first appears even though it doesn’t exist.

- Cool river names not shown on Franquelin’s map: Atokas (Cranberry River) and Fond Plat “Flat-bottom” (Sand River)

- The region west of today’s Herbster, Wisconsin is lablled “Papoishika.” I did an extensive post about an area called Ka-puk-wi-e-kah in that same location.

- Ici etoit une Bourgade Considerable: “Here there was a large village.” This in reference to when Chequamegon was a center for the Huron, Ottawa (Odawa) and other refugee nations of the Iroquois Wars in the mid-1600s.

- “La Petite Fille”: Little Girl’s Point.

- Chequamegon Bay is Baye St. Charles

- Catagane: Kakagon, Maxisipi: Mashkizibi

- The islands are “The 12 Apostles.”

British 1778

A new map of North America, from the latest discoveries 1778. Engrav’d for Carver’s Travels. In 1766 Jonathan Carver became one of the first Englishmen to pass through this region. His narrative is a key source for the time period directly following the conquest of New France, when the British claimed dominion over the Great Lakes.

- Lake Superior still has two giant islands in the middle of it.

- The Chipeway (Ojibwe), Ottaway (Odawa), and Ottagamie (Meskwaki/Fox) seem to have neatly delineated nations. The reality was much more complex. By 1778, the Ojibwe had moved inland from Lake Superior and were firmly in control of areas like Lac du Flambeau and Lac Courte Oreilles, which had formerly been contested by the Meskwaki.

Dutch 1805

Charte von den Vereinigten Staaten von Nord-America nebst Louisiana by F.L. Gussefeld: Published in Europe.

- The Dutch never had a claim to this region. In fact, this is a copy of a German map. However, it was too cool-looking to pass up.

- Over 100 years after Franquelin’s fairly-accurate outline of Lake Superior, much of Europe was still looking at this junk.

- “Ober See” and Tschippeweer” are funny to me.

- Isle Phillipeau is hanging on strong into the nineteenth century.

American 1805

A map of Lewis and Clark’s track across the western portion of North America, from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean : by order of the executive of the United States in 1804, 5 & 6 / copied by Samuel Lewis from the original drawing of Wm. Clark. This map was compiled from the manuscript maps of Lewis and Clark.

- The Chequamegon Region supposedly became American territory with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. The reality on the ground, however, was that the Ojibwe held sovereignty over their lands. The fur companies operating in the area were British-Canadian, and they employed mostly French-Ojibwe mix-bloods in the industry.

- This is a lovely-looking map, but it shows just how little the Americans knew about this area. Ironically, British Canada is very well-detailed, as is the route of Lewis and Clark and parts of the Mississippi that had just been visited by the American, Lt. Zebulon Pike.

- “Point Cheganega” is a crude islandless depiction of what we would call Point Detour.

- The Montreal River is huge and sprawling, but the Brule, Bad, and Ontonagon Rivers do not exist.

- To this map’s credit, there is only one Isle Royale. Goodbye Isle Phillipeaux. It was fun knowing you.

- It is striking how the American’s had access to decent maps of the British-Canadian areas of Lake Superior, but not of what was supposedly their own territory.

English 1811

A new map of North America from the latest authorities By John Cary of London. This map was published just before the outbreak of war between Britain and the United States.

- These maps are starting to look modern. The rivers are getting more accurate and the shape of Lake Superior is much better–though the shoreline isn’t done very well.

- Burntwood=Brule, Donagan=Ontonagon

- The big red line across Lake Superior is the US-British border. This map shows Isle Royale in Canada. The line stops at Rainy Lake because the fate of the parts of Minnesota and North Dakota in the Hudson Bay Watershed (claimed by the Hudson Bay Company) was not yet settled.

- “About this place a settlement of the North West Company”: This is Michel Cadotte’s trading post at La Pointe on Madeline Island. Cadotte was the son of a French trader and an Anishinaabe woman, and he traded for the British North West Company.

- It is striking that a London-made map created for mass consumption would so blatantly show a British company operating on the American side of the line. This was one of the issues that sparked the War of 1812. The Indian nations of the Great Lakes weren’t party to the Treaty of Paris and certainly did not recognize American sovereignty over their lands. They maintained the right to have British traders. America didn’t see it that way.

American 1820

Map of the United States of America : with the contiguous British and Spanish possessions / compiled from the latest & best authorities by John Melish

- Lake Superior shape and shoreline are looking much better.

- Bad River is “Red River.” I’ve never seen that as an alternate name for the Bad. I’m wondering if it’s a typo from a misreading of “bad”

- Copper mines are shown on the Donagon (Ontonagon) River. Serious copper mining in that region was still over a decade away. This probably references the ancient Indian copper-mining culture of Lake Superior or the handful of exploratory attempts by the French and British.

- The Brule-St. Croix portage is marked “Carrying Place.”

- No mention of Chequamegon or any of the Apostle Islands–just Sand Point.

- Isle Phillipeaux lives! All the way into the 1820s! But, it’s starting to settle into being what it probably was all along–the end of the Keweenaw mistakenly viewed from Isle Royale as an island rather than a peninsula.

American 1839

From the Map of Michigan and part of Wisconsin Territory, part of the American Atlas produced under the direction of U.S. Postmaster General David H. Burr.

- Three years before the Ojibwe cede the Lake Superior shoreline of Wisconsin, we see how rapidly American knowledge of this area is growing in the 1830s.

- The shoreline is looking much better, but the islands are odd. Stockton (Presque Isle) and Outer Island have merged into a huge dinosaur foot while Madeline Island has lost its north end.

- Weird river names: Flagg River is Spencer’s, Siskiwit River is Heron, and Sand River is Santeaux. Fish Creek is the gigantic Talking Fish River, and “Raspberry” appears to be labeling the Sioux River rather than the farther-north Raspberry River.

- Points: Bark Point is Birch Bark, Detour is Detour, and Houghton is Cold Point. Chequamegon Point is Chegoimegon Point, but the bay is just “The Bay.”

- The “Factory” at Madeline Island and the other on Long Island refers to a fur post. This usage is common in Canada: Moose Factory, York Factory, etc. At this time period, the only Factory would have been on Madeline.

- The Indian Village is shown at Odanah six years before Protestant missionaries supposedly founded Odanah. A commonly-heard misconception is that the La Pointe Band split into Island and Bad River factions in the 1840s. In reality, the Ojibwe didn’t have fixed villages. They moved throughout the region based on the seasonal availability of food. The traders were on the island, and it provided access to good fishing, but the gardens, wild rice, and other food sources were more abundant near the Kakagon sloughs. Yes, those Ojibwe married into the trading families clustered more often on the Island, and those who got sick of the missionaries stayed more often at Bad River (at least until the missionaries followed them there), but there was no hard and fast split of the La Pointe Band until long after Bad River and Red Cliff were established as separate reservations.

American 1843

Hydrographical basin of the upper Mississippi River from astronomical and barometrical observations, surveys, and information by Joseph Nicollet. Nicollet is considered the first to accurately map the basin of the Upper Mississippi. His Chequamegon Region is pretty good also.

- You may notice this map decorating the sides of the Chequamegon History website.

- This post mentions this map and the usage of Apakwa for the Bark River.

- As with the 1839 map, this map’s Raspberry River appears to be the Sioux rather than the Miskomin (Raspberry) River.

- Madeline Island has a little tail, but the Islands have their familiar shapes.

- Shagwamigon, another variant spelling

- Mashkeg River: in Ojibwe the Bad River is Mashkizibi (Swamp River). Mashkiig is the Ojibwe word for swamp. In the boreal forests of North America, this word had migrated into English as muskeg. It’s interesting how Nicollet labels the forks, with the White River fork being the most prominent.

That’s all for now folks. Thanks for covering 200 years of history with me through these maps. If you have any questions, or have any cool observations of your own, go ahead and post them in the comments.

…a donation of twenty-four sections of land covering the graves of our fathers, our sugar orchards, and our rice lakes and rivers…

March 29, 2013

Symbolic Petition of Chippewa Chiefs: Original birch bark petition of Oshkaabewis copied by Seth Eastman and printed in “Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States” by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (1851). Digitized by University of Wisconsin Libraries Wisconsin Electronic Reader project (1998).

For the first post on Chequamegon History, I thought I’d share my research into an image that has been circulating around the area for several years now. The image shows seven Ojibwe chiefs by their doodemag (clan symbols), connected by heart and mind to Lake Superior and to some smaller lakes. The clans shown are the Crane, Marten, Bear, Merman, and Bullhead.

All the interpretations I’ve heard agree that this image is a copy of a birch bark pictograph, and that it represents a unity among the several chiefs and their clans against Government efforts to remove the Lake Superior bands to Minnesota.

While there is this agreement on the why question of this petition’s creation, the who and when have been a source of confusion. Much of this confusion stems from efforts to connect this image to the famous La Pointe chief, Buffalo (Bizhiki/Gichi-weshkii).

In 2007, the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) released the short documentary Mikwendaagoziwag: They Are Remembered. While otherwise a very good overview of the Lake Superior Ojibwe in this era, it incorrectly uses this image to describe Buffalo going to Washington D.C. in 1849. Buffalo is famous for a trip to Washington in 1852, but he was not part of the 1849 group.

At the time the GLIFWC film was released, the Wisconsin Historical Society website referred to this pictograph as, “Chief Buffaloʼs Petition to the President,” and identified the crane as Buffalo. Citing oral history from Lac Courte Oreilles, the Society dated the petition after the botched 1850-51 removal to Sandy Lake, Minnesota that resulted in hundreds of Ojibwe deaths from disease and starvation due to negligence, greed, and institutional racism on the part of government officials. The Historical Society has since revised its description to re-date the pictograph at 1848-49, but it still incorrectly lists Buffalo, a member of the Loon Clan, as being depicted by the crane. The Sandy Lake Tragedy, has deservedly gained coverage by historians in recent years, but the pictographic petition came earlier and was not part of it.

If the Historical Society had contacted Chief Buffaloʼs descendants in Red Cliff, they would have known that Buffalo was from the Loon Clan. The relationship between the Loons and the Cranes, as far as which clan can claim the hereditary chieftainship of the La Pointe Band, is very interesting and covered extensively in Warrenʼs History of the Ojibwe People. It would make a good subject for a future post.

After looking into the history of this image, I can confidently say that Buffalo is not one of the chiefs represented. It was created before Sandy Lake and Buffalo’s journey, but it is related to those events. Here is the story:

In late 1848, a group of Ojibwe chiefs went to Washington. They wanted to meet directly with President James K. Polk to ask for a permanent reservations in Wisconsin and Michigan. At that time the Ojibwe did not hold title to any part of the newly-created state of Wisconsin or Upper Michigan, having ceded these lands in the treaties in 1837 and 1842. In signing the treaties, they had received guarantees that they could stay in their traditional villages and hunt, fish, and gather throughout the ceded territory. However, by 1848, rumors were flying of removal of all Ojibwe to unceded lands on the Mississippi River in Minnesota Territory. These chiefs were trying to stop that from happening.

John Baptist Martell, a mix-blood, acted as their guide and interpreter. The government officials and Indian agents in the west were the ones actively promoting removal, so they did not grant permission (or travel money) for the trip. The chiefs had to pay their way as they went by putting themselves on display and dancing as they went from town to town.

Martell was accused by government officials of acting out of self interest, but the written petition presented to congress asked for, “a donation of twenty-four sections of land covering the graves of our fathers, our sugar orchards, and our rice lakes and rivers, at seven different places now occupied by us at villages…” The chiefs claimed to be acting on behalf of the chiefs of all the Lake Superior bands, and there is reason to believe them given that their request is precisely what Chief Buffalo and other leaders continued to ask for up until the Treaty of 1854.

This written petition accompanied the pictographic petitions. It clearly states the goal of the the chiefs was to secure permanent reservations around the traditional villages east of the Mississippi.

The visiting Ojibwes made a big impression on the nationʼs capital and positive accounts of the chiefs, their families, and their interpreter appeared in the magazines of the day. Congress granted them $6000 for their expenses, which according to their critics was a scheme by Martell. However, it is likely they were vilified by government officials for working outside the colonial structure and for trying to stop the removal rather than for any ill-intentions of the part of their interpreter. A full scholarly study of the 1848-49 trip remains to be done, however.

Amid articles on the end of the slave trade, the California Gold Rush, and the benefits of the “passing away of the Celt” during the Great Irish Famine, two articles appeared in Littell’s Living Age magazine about the 1849 delegation. The first is tragic, and the second is comical.

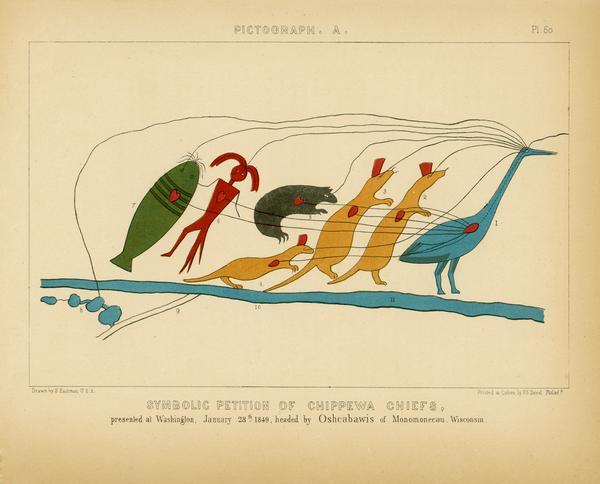

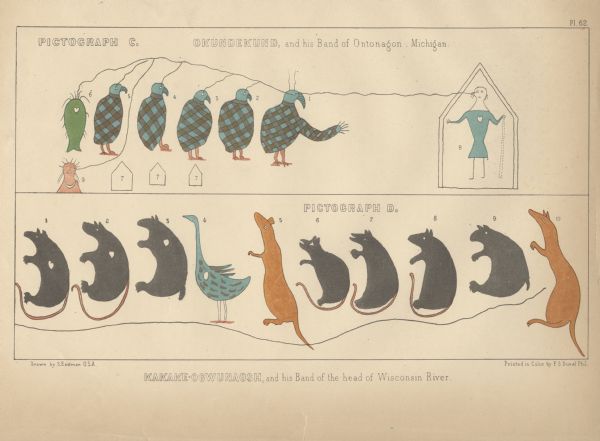

Along with written letters and petitions supporting the Ojibwe cause, the chiefs carried not only the one, but several birchbark pictographs. The pictographs show the clan animals of several chiefs and leading men from several small villages from the mouth of the Ontonagon River to Lac Vieux Desert in Upper Michigan and smaller satellite communities in Wisconsin. After seeing these petitions, the artist Seth Eastman copied them on paper and gave them to Henry Schoolcraft who printed and explained them alongside his criticism of the trip. They appear in his 1851 Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the United States.

Kenisteno, and his Band of Trout Lake, Wisconsin

Okundekund, and his Band of Ontonagon, Michigan (Upper) Kakake-ogwunaosh, and his Band of the head of Wisconsin River (Lower)

According to Schoolcraft, the crane in the most famous pictograph is Oshkaabewis, a Crane-clan chief from Lac Vieux Desert, and the leader of the 1848-49 expedition. In the Treaty of 1854, he is listed as a first chief from Lac du Flambeau in nearby Wisconsin. It makes sense that someone named Oshkaabewis would lead a delegation since the word oshkaabewis is used to describe someone who carries messages and pipes for a civil chief.

Kaizheosh [Gezhiiyaash], and his band from Lake Vieu Desert, Michigan and Wisconsin (University of Nebraska Libraries)

Long Story Short…

This is not Chief Buffalo or anyone from the La Pointe Band, and it was created before the Sandy Lake Tragedy. However it is totally appropriate to use the image in connection with those topics because it was all part of the efforts of the Lake Superior Ojibwe to resist removal in the late 1840s and early 1850s. However, when you do, please remember to credit the Lac Vieux Desert/Ontonagon chiefs who created these remarkable documents.