Martin Beaser

August 9, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

November 1888

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume IX, No.1, pages 24-27.

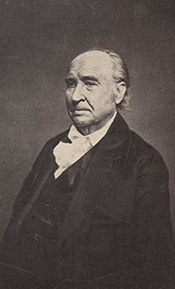

Martin Beaser.

Portrait of Martin Beaser on page 24.

On the fifth day of July 1854, Asaph Whittlesey and George Kilborn left La Pointe, in a row-boat, with the design of finding a “town site” on some available point near the “head of the bay.” At five o’clock P.M. of the same day they landed at the westerly limit of the present town site of Ashland. As Mr. Whittlesey stepped ashore, Mr. Kilborn exclaimed, “Here is the place for a big city!” and handing his companion an axe, he added, “I want you to have the honor of cutting the first tree in a way of a settlement upon the town site.” And the tree thus felled formed one of the foundation logs in the first building in the place. Such is the statement which has found its way into print as to the beginning of Ashland. But the same account adds: “Many new-comers arrived during the first few years after the settlement; among them Martin Beaser, who located permanently in Ashland in 1856, and was one of its founders.”1 How this was will soon be explained.

The father of the subject of this sketch, John Baptiste Beaser, was a native of Switzerland, educated as a priest, but never took orders. He came to America, reaching Philadelphia about the year 1812, where he married Margaret McLeod. They then moved to Buffalo, in one of the suburbs of which, called Williamsville, their son Martin was born, on the twenty-seventh of October, 1822. The boy received his early education in the common schools of the place, when, at the age of fourteen, he went on a whaling voyage, sailing from New Bedford, Massachusetts. His voyage lasted four years; his second voyage, three years; the last of which was made in the whaleship Rosseau, which is still afloat, the oldest of its class in America.

The young man went out as boat-steerer on his second voyage, returning as third mate. During his leisure time on shipboard and the interval between the two voyages, he spent in studying the science of navigation, which he successfully mastered. On his return from his fourth years’ cruise in the Pacific and Indian oceans, he was offered the position of second mate on a new ship then nearing completion and which would be ready to sail in about sixty days. He accepted the offer. They would notify him when the ship was ready, and he would in the meantime visit his mother, then a widow, residing in Buffalo. Accordingly, after an absence of seven years, he returned to his native city, spending the time in renewing old acquaintances and relating the varied experience of a whaler’s life. He had rare conversational powers, holding his listeners spell-bound at the recital of some thrilling adventure. A journal kept by him during his voyages and now in the possession of his family, abounds in hair-breadth escapes from savages on the shores of some of the South sea islands and the perils of whale-fishing, of which he had many narrow escapes. The time passed quickly, and he anxiously awaited the summons to join his ship. Leaving the city for a day the expected letter came, but was carefully concealed by his mother until after the ship had sailed, thus entirely changing the future of his life.

“… Martin, a sailor just from the whaling grounds of the Northwest Coast …”

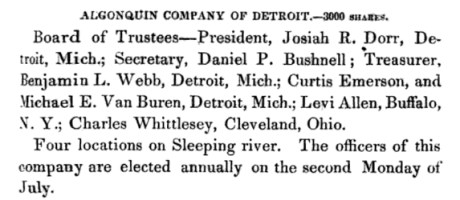

Disappointed in his aspirations to command a ship in the near future, as he had reasons to hope from the rapid promotions he had already received – from a boy before the mast to mate of a ship in two voyages – and yielding to his mother’s wish not to leave home again, he engaged in sailing on Lake Erie from Buffalo to Detroit until 1847, when he went in the interest of a company in the latter city to Lake Superior for the purpose of exploring the copper ranges in the northern peninsula of Michigan. He coasted from Sault Ste. Marie to Ontonagon in a bateau. Remaining in the employ of the company about a year, he then engaged in a general forwarding and commission business for himself.

“Algonquin Company of Detroit.”

~ Reports of Wm. A. Burt and Bela Hubbard, by T. W. Bristol, 1846, page 97.

~ A History of the Northern Peninsula of Michigan and Its People: Volume 1, by Alvah Littlefield Sawyer, 1911, page 222.

Mr. Beaser was largely identified with the early mining interests of Ontonagon county, being instrumental in opening up and developing some of the best mines in that district.

In 1848 he was married in Cattaraugus county, New York, in the town of Perrysburgh, to Laura Antionette Bebee. The husband and wife the next spring went west, going to Ontonagon by way of Detroit. The trip from buffalo lasted from the first day of May to the sixth of June, they being detained at the “Soo” two weeks on account of the changing of the schooner Napoleon into a propeller, in which vessel, after a voyage of six days, they reached Ontonagon.

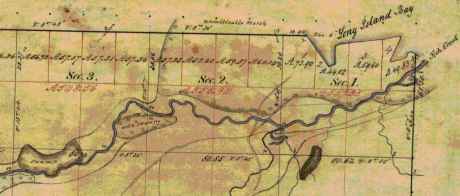

Here Mr. Beaser resided for seven years in the same business of forwarding and commission, furnishing frequently powder and candles to the miners by the ton. He was a portion of the this time associated with Thomas B. Hanna, formerly of Ohio. They then sold out their interest – Mr. Beaser going in company with Augustus Coburn and Edward Sayles to Superior, at the head of the lake, taking a small boat with them and Indian guides. Thus equipped they explored the region of Duluth, going up the Brule and St. Louis rivers. They then returned to La Pointe, going up Chaquamegon bay; and having their attention called to the site of what is now Ashland, on account of what seemed to be its favorable geographical position. As there had been some talk of the feasibility of connecting the Mississippi river and Lake Superior by a ship canal, it was suggested to them that this point would be a good one for its eastern terminus. Another circumstance which struck them was the contiguity of the Penokee iron range. This was in 1853. The company then returned to Ontonagon.

Closing up his business at the latter place, Mr. Beaser decided to return to the bay of Chaquamegon to look up and locate the town site on its southern shore. In the summer of 1854, on arriving there, he found Mr. Whittlesey and Mr. Kilborn on the ground. He then made arrangement with them by which he (Mr. Beaser) was to enter the land, which he did at Superior, where the land office was then located for that section. The contract between the three was, that Mr. Whittlesey and Mr. Kilborn were to receive each an eighth interest in the land, while the residue was to go to Mr. Beaser. The patent for the land was issued to Schuyler Goff, as county Judge of La Pointe county, Wisconsin, who was the trustee for the three men, under the law then governing the location of town sites.

La Pointe County Judge Schuyler Goff was issued this patent for 280.53 acres on June 23rd, 1862, on behalf of Martin Beaser, Asaph Whittlesey, and George Kilburn.

~ General Land Office Records

Mr. Beaser afterwards got his deed from the judge to his three-quarters’ interest in the site.

Beaser named Ashland in honor of the Henry Clay Estate in Kentucky.

~ National Park Service

In January, 1854, Mr. Beaser having previously engaged a topographical engineer, G.L. Brunschweiler, the two, with a dog train and two Indians, made the journey from Ontonagon to the proposed town site, where Mr. Brunschweiler surveyed and platted2 a town on the land of the men before spoken of as parties in interest, to which town Mr. Beaser gave the name of Ashland. These three men, therefore, were the founders of Ashland, although afterwards various additions were made to it.

Mr. Beaser did not bring his family to Ashland until the eighth of September, 1856. He engaged in the mercantile business there until the war broke out, and was drowned in the bay while attempting to come from Bayfield to Ashland in an open boat, during a storm, on the fourth of November, 1866. He was buried on Madeline island at La Pointe. He was “closely identified with enterprises tending to open up the country; was wealthy and expended freely; was a man of fine discretion and good, common sense.” He was never discouraged as to Ashland’s future prosperity.

The children of Mr. Beaser, three in number, are all living: Margaret Elizabeth, wife of James A. Croser of Menominee, Michigan; Percy McLeod, now of Ashland; and Harry Hamlin, also of Ashland, residing with his mother, now Mrs. Wilson, an intelligent and very estimable lady.

1 See ‘History of Northern Wisconsin,’ p. 67.

2 The date of the platting of Ashland by Brunschweiler is taken from the original plat in the possession of the recorder of Ashland county, Wisconsin.

Samuel Stuart Vaughn

August 8, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

November 1888

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume IX, No. 1, pages 17-21.

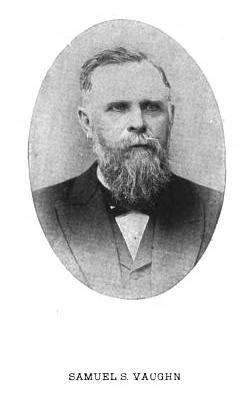

Samuel Stuart Vaughn.

Of the pioneers upon the southern shores of Lake Superior, none stand higher in the memory of those now living there than Samuel Stuart Vaughn. He was born at Berea, Cuyahoga county, Ohio, on the second of September, 1830. His parents were Ephraim Vaughn and Eunice Stewart Vaughn. Samuel was the youngest in a family of five children – two daughters and three sons. Although at a very early age possessed of a great desire for an education, he was, to a large extent, denied the advantages of schools, owing to the fact that his father was in straitened circumstances financially. It is related of the boy Samuel that he picked up chestnuts at one time, and took them into Cleveland, where he disposed of them to purchase a geography [book?] he wanted. Three months was the whole extent of his time passed in the common schools of his native place – surely a brief period, and one sorely regretted for its brevity by a boy who, even then, hungered and thirsted for knowledge.

~ FindAGrave.com

In 1849 the young man came to Eagle River, Michigan, where he engaged himself to his brother as clerk. He remained there until 1852, when the brothers removed to La Pointe, Wisconsin, reaching that place on the fourth of August. He now opened a store, and engaged in trading with the Indians and fishermen of the island and surrounding country. La Pointe was then the county seat of a county of the same name in Wisconsin, and a place of considerable importance, though its glory has since departed.

Vaughn advertisement from the August 22nd, 1857, issue of the Bayfield Mercury newspaper.

~ NewspaperArchive.com

Young Vaughn spoke the French and Chippewa languages fluently. This accomplishment was absolutely necessary, in the early days of this region of country to make a man successful as a trader. He was very fond of reading, particularly works of history, and through all his pioneer life his books were his loved companions. His taste was not for worthless books, but for those of an improving character; hence he received a large amount of benefit from his silent teachers.

In his relation with the Indians, which, owing to the nature of his business, were quite intimate, Mr. Vaughn commanded their fullest confidence. It is related that when at one time there were rumors of trouble between the white people and the Chippewas, and many of the settlers became frightened and feared they would be murdered by the natives, a delegation of chiefs came to him and said they wanted to have a talk. They said they had heard of the fears of the whites, but assured him there was nothing to be afraid of; the Indians would do no harm, “for,” said they, “we know that the soldiers of the white man are like the sands of the sea in numbers, and if we make any trouble they will come and overpower us.” Mr. Vaughn was abundantly satisfied of their sincerity as well as of their peaceful disposition, and he soon quieted the fears of the settlers.

“Being impressed,” says a writer who knew him well,

“with the future possibilities of this country and ambitious, to use a favorite expression of his own, to become ‘a man among men,’ he recognized the disadvantage under which he labored from the limited educational advantages he had enjoyed in his youth, and his first earnings were devoted to remedying his deficiency in this respect. Closing his business at La Pointe, he returned to his native state, where a year was spent in preparatory studies, which were pursued with a full realization of their importance to his future career. He spent several months in Cleveland acquiring a ‘business education.’ He became a systematic bookkeeper, careful in his transactions and persevering in his plans. Having devoted as much time to the special course of instruction marked out by him as his limited means would afford, he returned to La Pointe, at that time the only white settlement in all this region, where he remained until 1856.” 1

Mr. Vaughn, during the year just named, removed to Bayfield, the town site having been previously surveyed and platted. It was opposite La Pointe on the mainland, and is now the county-seat of Bayfield county, Wisconsin. There he erected the first stone building,2 built also a saw-mill, and engaged in the sale of general merchandise and in the manufacture of lumber. “In his characteristic manner,” says the writer just quoted,

“of doing with all his might whatever his hands found to do, he at once took a leading position in all matters of private and public interest which go to the building up of a prosperous community.”

Mr. Vaughn built what is known as Vaughn’s dock in Bayfield, and remained in that town until 1872. Meanwhile, he was married in Solon, Ohio, to Emeline Eliza Patrick. This event took place on the twenty-second of December, 1864. After spending a few months among friends in Ohio, he brought his wife west to share his frontier life. The wedding journey was made in February, 1865, the two going first to St. Paul; thence they journeyed to Bayfield by sleigh, “partly over logging roads, and partly over no road.” It was a novel experience to the bride, but one which she had no desire to shrink from. She was not the wife to be made unhappy by ordinary difficulties.

As early as the twenty-fifth of October, 1856, Mr. Vaughn had preëmpted one hundred and sixty acres of land, afterwards known as “Vaughn’s division of Ashland.” He was one of the leading spirits in the projection of the old St. Croix & Lake Superior railroad, and contributed liberally of his time and money in making the preliminary organizations and surveys. Being convinced, from the natural location of Ashland, that it would become in the future a place of importance, was the reason which induced him to preëmpt the land there, of which mention has just been made.

Vaughn was issued his patent to 40 acres in Ashland on June 1st, 1859. The other 120 acres of his preemption are not accounted for in these records.

~ General Land Office Records

As may be presumed, Mr. Vaughn omitted no opportunity of calling the attention of capitalists to the necessity of railroad facilities for northern Wisconsin. He became identified with the early enterprises organized for the purpose of building a trunk line from the southern and central portions of the state to Lake Superior, and was for many years a director in the old “Winnebago & Lake Superior” and “Portage & Lake Superior” Railroad companies, which, after many trials and tribulations, were consolidated, resulting in the building of the pioneer road – the Wisconsin Central.

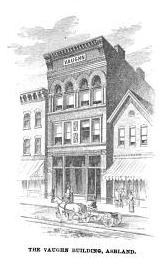

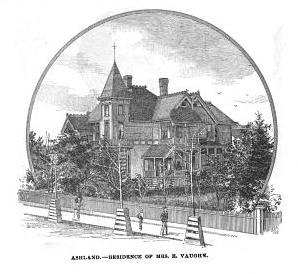

In 1871, upon the completion of the survey of the Wisconsin Central railroad, he proceeded to lay out his portion of the town of Ashland, and made arrangements for the transfer of his business thither from Bayfield. During the next year he made extensive improvements to his new home; these included the building of a residence, the erection of a store, also (in company with Mr. Charles Fisher) of a commercial dock. The Wisconsin Central railroad had begun work at the bay (Chaquamegon); and, at this time, many settlers were coming in. In the fall he moved into his new house, becoming, with his wife, a permanent resident of Ashland.

Mr. Vaughn and his partner just named received at their dock large quantities of merchandise by lake, and they took heavy contracts to furnish supplies to the railroad before mentioned. In the fall of 1872 they established branch stores at Silver creek and White river to furnish railroad men with supplies. They also had contracts to get out all the ties used by the railroad between Ashland and Penokee. In 1875 the firm was dissolved, and Mr. Vaughn continued in business until 1881, when he sold out, but continued to handle coal and other merchandise at his dock. In the winter previous he put in 10,000,000 feet of logs.

Mr. Vaughn represented the counties of Ashland, Barren, Bayfield, Burnett, Douglas and Polk in the thirty-fourth regular session of the Wisconsin legislature, being a member of the assembly for the year 1871. These counties, according to the Federal census of the year previous, contained a population of 6,365. His majority in the district over Issac I. Moore, Democrat, was 398. Mr. Vaughn was in politics a Republican. Previous to this time he had been postmaster for four years at Bayfield. He was several times called to the charge of town and county affairs as chairman of the board of supervisors, and in every station was faithful, as well as equal, to his trust; but he was never ambitious for political honors. He died at his home in Ashland of pneumonia, on the twenty-ninth day of January, 1886.

Mr. Vaughn was one of the most prominent men in northern Wisconsin, and one of the wealthiest citizens of Ashland at the time of his decease. He had accumulated a large amount of real estate in Ashland and Bayfield, and held heavy iron interests in the Gogebic district; but, at the same time, he was a man of charitable nature, being a member of several charitable orders and societies. He was a member of Ashland Lodge, I.O.O.F., and one of its foremost promoters and supporters. Mr. Vaughn was also a Mason, being a member of Wisconsin Consistory, Chippewa Commandery, K.T., Ashland Chapter, R.A.M., and Ancient Landmark Lodge, F. and A.M.

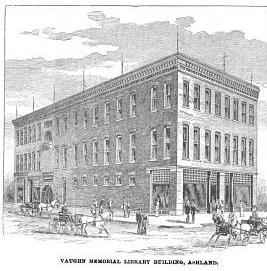

Although an unostentatious man, Mr. Vaughn was possessed of much public spirit, and the remark had been common in Ashland since his death, by those who knew him best, that the city had lost its best man. Certain it is that he was possessed of great enterprise, and was always ready with his means to help forward any scheme that he saw would benefit the community in which he lived. It had long been one of his settled determinations to appropriate part of his wealth to the establishment of a free library in Ashland. So it was that before his death the site had been chosen by him for the building, and a plan of the institution formulated in his mind, intending soon to make a reality of his day-dreams concerning this undertaking; but death cut short his plans.

It is needless to say to those who know to whom was confided the whole subject of the “Vaughn Library,” that it has not been allowed to die out. In his will Mr. Vaughn left hall his property to his wife, and she nobly came forward to make his known desires with regard to the institution a fixed fact. The corner-stone of the building for the library was laid, with imposing ceremonies, on the fourteenth of July, 1887, and a large number of books will soon be purchased to fill the shelves now nearly ready for them. It will be, in the broadest sense, a public library – free to all; and will surely become a lasting and proud monument to its generous founder, Samuel Stewart Vaughn. She who was left to carry out the noble schemes planned by the subject of this sketch, now the wife of the Rev. Angus Mackinnon, deserves particular mention in this connection. She is a lady of marked characteristics, all of which go to her praise. Soon after reaching her home in the west she taught some of the Bayfield Indians to read and write; and from that time to the present, has proved herself in many ways of sterling worth to northern Wisconsin.

“Years ago, when Ashland consisted of a few log houses and a half dozen stores – before there was even a rail through the woods that lead to civilization many miles away – this lady was a member of ‘Literary,’ organized by a half-dozen progressive young people; and in a paper which she then read on ‘The Future of Ashland,’ she predicted nearly everything about the growth of the place that has taken place during the past few years – the development of the iron mines, railroads, iron furnaces, water-works, paved streets, and, to a dot, the present limits of its thoroughfares. She is a representative Ashland lady.”

1 Samuel S. Fifield in the Ashland Press of February 6, 1886.

2 This was the second house in the place.

Another biographical sketch and this portrait of Samuel Stuart Vaughn are available on pages 80-81 of Commemorative Biographical Record of the Upper Lake Region by J.H. Beers & Co., 1905.

Among The Otchipwees: III

July 20, 2016

By Amorin Mello

… continued from Among The Otchipwees: II

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 4 February 1885

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 335-342.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

III.

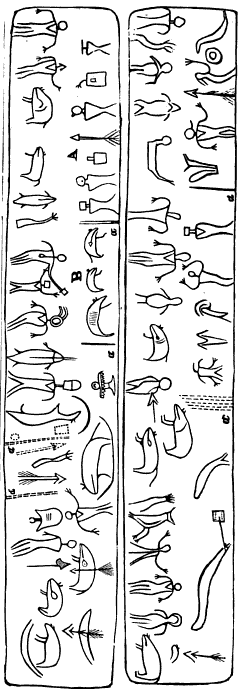

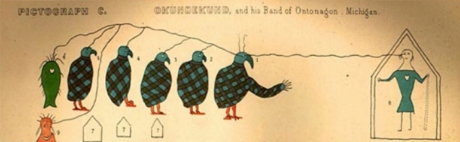

The Northern tribes have nothing deserving the name of historical records. Their hieroglyphics or pictorial writings on trees, bark, rocks and sheltered banks of clay relate to personal or transient events. Such representations by symbols are very numerous but do not attain to a system.

Their history prior to their contact with the white man has been transmitted verbally from generation to generation with more accuracy than a civilized people would do. Story-telling constitutes their literature. In their lodges they are anything but a silent people. When their villages are approached unawares, the noise of voices is much the same as in the camps of parties on pic-nic excursions. As a voyageur the pure blood is seldom a success, and one of the objections to him is a disposition to set around the camp-fire and relate his tales of war or of the hunt, late into the night. This he does with great spirit, “suiting the action to the word” with a varied intonation and with excellent powers of description. Such tales have come down orally from old to young many generations, but are more mystical than historical. The faculty is cultivated in the wigwam during long winter nights, where the same story is repeated by the patriarchs to impress it on the memory of the coming generation. With the wild man memory is sharp, and therefore tradition has in some cases a semblance to history. In substance, however, their stories lack dates, the subjects are frivolous or merely romantic, and the narrator is generally given to embellishment. He sees spirits everywhere, the reality of which is accepted by the child, who listens with wonder to a well-told tale, in which he not only believes, but is preparing to be a professional story-teller himself.

Indian picture-writings and inscriptions, in their hieroglyphics, are seen everywhere on trees, rocks and pieces of bark, blankets and flat pieces of wood. Above Odanah, on Bad River, is a vertical bank of clay, shielded from storms by a dense group of evergreens. On this smooth surface are the records of many generations, over and across each other, regardless of the rights of previous parties. Like most of their writings, they relate to trifling events of the present, such as the route which is being traveled; the game killed; or the results of a fight. To each message the totem or dodem of the writer is attached, by which he is at once recognized. But there are records of some consequence, though not strictly historical.

Charles Whittlesey also reproduced Okandikan’s autobiography in Western Reserve Historical Society Tract 41.

Before a young man can be considered a warrior, he must undergo an ordeal of exposure and starvation. He retires to a mountain, a swamp, or a rock, and there remains day and night without food, fire or blankets, as long as his constitution is able to endure the exposure. Three or four days is not unusual, but a strong Indian, destined to be a great warrior, should fast at least a week. One of the figures on this clay bank is a tree with nine branches and a hand pointing upward. This represents the vision of an Indian known to one of my voyagers, which he saw during his seclusion. He had fasted nine days, which naturally gave him an insight of the future, and constituted his motto, or chart of life. In tract No. 41 (1877), of the Western Reserve Historical Society, I have represented some of the effigies in this group; and also the personal history of Kundickan, a Chippewa, whom I saw in 1845, at Ontonagon. This record was made by himself with a knife, on a flat piece of wood, and is in the form of an autobiography. In hundreds of places in the United States such inscriptions are seen, of the meaning of which very little is known. Schoolcraft reproduced several of them from widely separated localities, such as the Dighton Boulder, Rhode Island; a rock on Kelley’s Island, Lake Erie, and from pieces of birch bark, conveying messages or memoranda to aid an orator in his speeches.

~ New Sources of Indian History, 1850-1891: The Ghost Dance and the Prairie Sioux, A Miscellany by Stanley Vestal, 2015, page 269.

The “Indian rock” in the Susquehanna River, near Columbia, Pennsylvania; the God Rock, on the Allegheny, near Brady’s Bend; inscriptions on the Ohio River Rocks, near Wellsville, Ohio, and near the mouth of the Guyandotte, have a common style, but the particular characters are not the same. Three miles west of Barnsville, in Belmont County, Ohio, is a remarkable group of sculptured figures, principally of human feet of various dimensions and uncouth proportions. Sitting Bull gave a history of his exploits on sheets of paper, which he explained to Dr. Kimball, a surgeon in the army, published in fascimile in Harper’s Weekly, July 1876. Such hieroglyphics have been found on rocky faces in Arizona, and on boulders in Georgia.

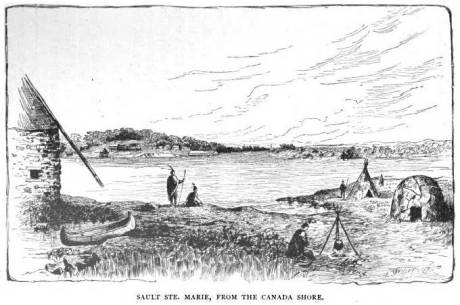

Pointe De Froid is the northwestern extremity of La Pointe on Madeline Island. Map detail from 1852 PLSS survey.

~ Report of a geological survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota: and incidentally of a portion of Nebraska Territory, by David Dale Owen, 1852, page 420.

~ Geology of Wisconsin: Paleontology by R. P. Whitfield, 1880, page 58.

While pandemonium was let loose at La Pointe towards the close of the payment we made a bivouac on the beach, between the dock and the mission house. The voyageurs were all at the great finale which constitutes the paradise of a Chippewa. One of my local assistants was playing the part of a detective on the watch for whisky dealers. We had seen one of them on the head waters of Brunscilus River, who came through the woods up the Chippewa River. Beyond the village of La Pointe, on a sandy promontory called Pointe au Froid, abbreviated to Pointe au Fret or Cold Point, were about twenty-five lodges, and probably one hundred and fifty Indians excited by liquor. For this, diluted with more than half water, they paid a dollar for each pint, and the measure was none too large – neither pressed down nor running over. Their savage yells rose on the quiet moon-lit atmosphere like a thousand demons. A very little weak whisky is sufficient to work wonders in the stomach of a backwoods Indian, to whom it is a comparative stranger. About midnight the detective perceived our traveler from the Chippewa River quietly approaching the dock, to which he tied his canoe and went among the lodges. To the stern there were several kegs of fire-water attached, but weighted down below the surface of the water. It required but a few minutes to haul them in and stave the heads of all of them. Before morning there appeared to be more than a thousand savage throats giving full play to their powerful lungs. Two of them were staggering along the beach toward where I lay, with one man by my side. he said we had better be quiet, which, undoubtedly, was good advice. They were nearly naked, locked arm in arm, their long hair spread out in every direction, and as they swayed to and fro between the water line and the bushes, no imagination could paint a more complete representation of the demon. There was a yell to every step – apparently a bacchanalian song. They were within two yards before they saw us, and by one leap cleared everything, as though they were as much surprised as we were. The song, or howl, did not cease. It was kept up until they turned away from the beach into the mission road, and went on howling over the hill toward the old fort. It required three days for half-breed and full-blood alike to recover from the general debauch sufficiently to resume the oar and pack. As we were about to return to the Penoka Mountains, a Chippewa buck, with a new calico shirt and a clean blanket, wished to know if the Chemokoman would take him to the south shore. He would work a paddle or an oar. Before reaching the head of the Chegoimegon Bay there was a storm of rain. He pulled off his shirt, folded it and sat down upon it, to keep it dry. The falling rain on his bare back he did not notice.

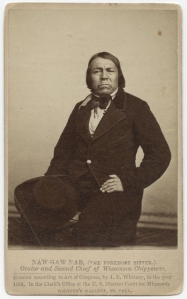

Portrait of Stephen Bonga

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

We had made the grand portage of nine miles from the foot of the cataract of the St. Louis, above Fond du Lac, and encamped on the river where the trail came to it below the knife portage. In the evening Stephen Bungo, a brother of Charles Bungo, the half-breed negro and Chippewa, came into our tent. He said he had a message from Naugaunup, second chief of the Fond du Lac band, whose home as at Ash-ke-bwau-ka, on the river above. His chief wished to know by what authority we came through the country without consulting him. After much diplomatic parley Stephen was given some pequashigon and went to his bivouac.

Joseph Granville Norwood

~ Wikipedia.org

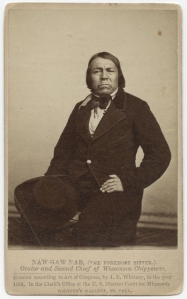

Portrait of Naagaanab

~ Minnesota Historical Society

The next morning he intimated that we must call at Naugaunup’s lodge on the way up, where probably permission might be had, by paying a reasonable sum, to proceed. We found him in a neat wigwam with two wives, on a pleasant rise of the river bluff, clear of timber, where there had been a village of the same name. His countenance was a pleasant one, very closely resembling that of Governor Corwin, of Ohio, but his features were smaller and also his stature. Dr. Norwood informed him that we had orders from the Great Father to go up the St. Louis to its source, thence to the waters running the other way to the Canada line. Nothing but force would prevent us from doing this, and if he was displeased he should make a complaint to the Indian agent at La Pointe, and he would forward it to Washington. We heard no more of the invasion of his territory, and he proceeded to do what very few Chippewas will do, offered to show us valuable minerals. In the stream was a pinnacle of black sale, about sixty feet high. Naugaunup soon appeared from behind it, near the top, in a position that appeared to be inaccessible, a very picturesque object pointing triumphantly to some veins of white quartz, which are very common in metamorphic slate.

Those who have heard him, say that he was a fine orator, having influence over his band, a respectable Indian, and a good negotiator. If he imagined there was value in those seams of quartz it is quite remarkable and contrary to universal practice among Chippewas that he should show them to white men. They claim that all minerals belong to the tribe. An Indian who received a price for showing them, and did not give every one his share, would be in danger of his life. They had also a superstitious dread of some great evil if they disclosed anything of the kind. Some times they promise to do so, but when they arrive at the spot, with some verdant white man, expecting to become suddenly rich, the Great Spirit or the Bad Manitou has carried it away. I have known more than one such instance, where persons have been sustained by hopeful expectation after many days of weary travel into the depths of the forest. The editor of the Ontonagon Miner gives one of the instances in his experience:

“Many years ago when Iron River was one of the fur stations, of John Jacob Astor and the American Fur Company, the Indians were known to have silver in its native state in considerable quantities.”

Men are now living who have seen them with chunks of the size of a man’s fist, but no one ever succeeded in inducing them to tell or show where the hidden treasure lay. A mortal dread clung to them, that if they showed white men a deposit of mineral the Great Manitou would punish them with death.

Several years since a half-breed brought in very fine specimens of vein rock, carrying considerable quantities of native silver. His report was that his wife had found it on the South Range, where they were trapping. To test his story he was sent back for more. In a few days he returned bringing with him quite a chunk from which was obtained eleven and one-half ounces of native silver. He returned home, went among the Flambeaux Indians and was killed. His wife refused to listen to any proposals or temptation from friend or foe to show the location of this vein, clinging with religious tenacity to the superstitious fears of her tribe.

When the British had a fort on St. Joseph’s Island in the St. Mary’s River, in the War of 1812, an Indian brought in a rich piece of copper pyrites. The usual mode of getting on good terms with him, by means of whisky, failed to get from him the location of the mineral. Goods were offered him; first a bundle, then a pile, afterwards a canoe-load, and finally enough to load a Mackinaw boat. No promise to disclose the place, no description or hint could be extorted. It was probably a specimen from the veins on the Bruce or Wellington mining property, only about twenty miles distant on the Canadian shore.

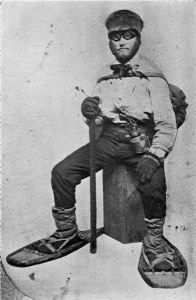

Detail of John Beargrease the Younger from stereograph “Lake Superior winter mail line” by B. F. Childs, circa 1870s-1880s.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

Crossing over the portage from the St. Louis River to Vermillion River, one of the voyageurs heard the report of a distant shot. They had expected to meet Bear’s Grease, with his large family, and fired a gun as a signal to them. The ashes of their fire were still warm. After much shouting and firing, it was evident that we should have no Indian society at that time. That evening, around an ample camp fire, we heard the history of the old patriarch. His former wives had borne him twenty-four children; more boys than girls. Our half-breed guide had often been importuned to take one of the girls. The old father recommended her as a good worker, and if she did not work he must whip her. Even a moderate beating always brought her to a sense of her duties. All he expected was a blanket and a gun as an offset. He would give a great feast on the occasion of the nuptials. Over the summit to Vermillion, through Vermillion Lake, passing down the outlet among many cataracts to the Crane Lake portage, there were encamped a few families, most of them too drunk to stand alone. There were two traders, from the Canada side, with plenty of rum. We wanted a guide through the intricacies of Rainy Lake. A very good-looking savage presented himself with a very unsteady gait, his countenance expressing the maudlin good nature of Tam O’Shanter as he mounted Meg. Withal, he appeared to be honest. “Yes, I know that way, but, you see, I’m drunk; can’t you wait till to-morrow.” A young squaw who apparently had not imbibed fire-water, had succeeded in acquiring a pewter ring. Her dress was a blanket of rabbit skins, made of strips woven like a rag carpet. It was bound around her waist with a girdle of deer’s hide, answering the purpose of stroud and blanket. No city belle could exhibit a ring of diamonds more conspicuously and with more self-satisfaction than this young squaw did her ring of pewter.

As we were all silently sitting in the canoes, dripping with rain, a sudden halloo announced the approach of living men. It was no other than Wau-nun-nee, the chief of the Grand Fourche bands, who was hunting for ducks among the rice. More delicious morsels never gladdened the palate than these plump, fat, rice-fed ducks. Old Wau-nun-nee is a gentleman among Indian chiefs. His band had never consented to sell their land, and consequently had no annuities. He even refused to receive a present from the Government as one of the head men of the tribe, preferring to remain wholly independent. We soon came to his village on Ash-ab-ash-kaw Lake. No band of Indians in our travels appeared as comfortable or behaved as well as this. Their country is well supplied with rice and tolerably good hunting ground. The American fur dealers (I mean the licensed ones) do not sell liquor to the Indians, and use their influence to aid Government in keeping it from them. Wau-nun-nee’s baliwick was seldom disturbed by drunken brawls. His Indians had more pleasant countenances than any we had seen, with less of the wild and haggard look than the annuity Indians. It was seldom they left their grounds, for they seldom suffered from hunger. They were comfortably clothed, made no importunities for kokoosh or pequashigon, and in gratifying their savage curiosity about our equipments they were respectful and pleasant. In his lodge the chief had teacups and saucers, with tea and sugar for his white guests, which he pressed us to enjoy. But we had no time for ceremonials, and had tea and sugar of our own. Our men recognized numerous acquaintances among the women, and as we encamped near a second village at Round Lake they came to make a draft on our provision chest. We here laid in a supply of wild rice in exchange for flour. Among this band we saw bows and arrows used to kill game. They have so little trade with the whites, and are so remote from the depots of Indian goods, that powder and lead are scarce, and guns also. For ducks and geese the bow and arrow is about as effectual as powder and shot. In truth, the community of which Wau-nun-nee was the patriarch came nearer to the pictures of Indians which poets are fond of drawing than any we saw. The squaws were more neatly clad, and their hair more often combed and braided and tied with a piece of ribbon or red flannel, with which their pappooses delighted to sport. There were among them fewer of those distinguished smoke-dried, sore-eyed creatures who present themselves at other villages.

By my estimate the channel, as we followed it to the head of the Round Lake branch, is two hundred and two mile in length, and the rise of the stream one hundred and eight feet. The portage to a stream leading into the Mississippi is one mile.

At Round Lake we engaged two young Indians to help over the portage in Jack’s place. Both of them were decided dandies, and one, who did not overtake us till late the next morning, gave an excuse that he had spent the night in courting an Indian damsel. This business is managed with them a little differently than with us. They deal largely in charms, which the medicine men furnish. This fellow had some pieces of mica, which he pulverized, and was managing to cause his inamorata to swallow. If this was effected his cause was sure to succeed. He had also some ochery, iron ore and an herb to mix with the mica. Another charm, and one very effectual, is composed of a hair from the damsel’s head placed between two wooden images. Our Lothario had prepared himself externally so as to produce a most killing effect. His hair was adorned with broad yellow ribbons, and also soaked in grease. On his cheeks were some broad jet black stripes that pointed, on both sides, toward his mouth; in his ears and nose, some beads four inches long. For a pouch and medicine bag he had the skin of a swan suspended from his girdle by the neck. His blanket was clean, and his leggings wrought with great care, so that he exhibited a most striking collection of colors.

At Round Lake we overtook the Cass Lake band on their return from the rice lakes. This meeting produced a great clatter of tongues between our men and the squaws, who came waddling down a slippery bank where they were encamped. There was a marked difference between these people and those at Ash-ab-ash-kaw. They were more ragged, more greasy, and more intrusive.

CHARLES WHITTLSEY.

Among The Otchipwees: II

June 4, 2016

By Amorin Mello

… continued from Among The Otchipwees: I

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 3 January 1885

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 177-192.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

II.

In the fall of 1849, the Bad Water band were in excellent condition, and therefore very happy. Deer were then very abundant on the Menominee. They are nimble animals, able to leap gracefully over obstructions as high as a man’s head standing. But they do not like such efforts, unless there is a necessity for it. The Indians discovered this long ago, and built long brush fences across their trails to the water. When the unsuspecting animal has finished browsing, he goes for a drink with the regularity of an habitué of a saloon. Seeing the obstruction, he walks leisurely along it, expecting to find a low place, or the end of it. The dark eye of the Chippewa is fixed upon him from the top of a tree. This is much the best position, because the deer is not likely to look up, and the wind is less likely to bear his odor to the delicate nostrils of the game. At such close quarters every shot is fatal. Its throat is cut, its legs tied together, and thrown over the head and shoulders of the hunter, its body resting on his back, and he starts for the village. Here the squaws strip off the hide and prepare the carcass for the kettle. With a tin cup full of flour or a pound of pork, we often purchased a saddle of venison, and both parties were satisfied with the trade.

Naagaanab

~ Minnesota Historical Society

~ Executive Documents of the State of Minnesota for the Year 1886, Volume V.: Minnesota Geographical Names Derived from the Chippewa Language, by Reverend Joseph Alexander Gilfillan, 1887, page 457.

“Akwaakwaa” refers to “go a certain distance in the woods.”

~ General Geology: Miscellaneous Papers, Volume 1: A Report of Explorations in the Mineral Regions of Minnesota During the Years 1848, 1859 and 1864 by Colonel Charles Whittlesey, 1866, page 44.

Of course the man of the woods has a preference as to what he shall eat; but when he is suffering from hunger, as he is a large part of his days, he is not very particular. Fresh venison, bear meat, buffalo, moose, caribou, porcupine, wild geese, ducks, rabbits, pigeons, or fish, relish better than gulls, foxes, or skunks. The latter do very well while he is on the verge of starvation, and even owls, crows, dead horses and oxen. The lakes of the interior of Minnesota and Wisconsin produce wild rice spontaneously. When parched it is more palatable than southern rice, and more nutritious. Potatoes grow well everywhere in the north country; varieties of corn ripen as far north as Red Lake. Nothing but a disinclination to labor hinders the Chippewa from always having enough to eat. With the wild rice, sugar, and the fat of animals, well mixed, they make excellent rations, which will sustain life longer than any preparation known to white men. A packer will carry on his back enough to last him forty days. He needs only a tin cup in which to warm water, with which it makes a rich soup. Pemmican is less palatable, and sooner becomes rancid. This is made of smoke or jerked meat pulverized, saturated with fat and pressed into cakes or blocks. Sturgeon are numerous and large, and when well smoked and well pulverized they furnish palatable food even without salt, and keep indefinitely. Voyagers mix it with sugar and water in their cups. In the large lakes, white fish, siskowit, and lake trout are abundant. In the smaller lakes and rivers there are many varieties of fish. With so many resources supplied by nature, if the natives suffer from hunger it is solely caused by indolence. His implicit reliance upon the Great Spirit, which is his good Providence, no doubt encourages improvidence. Nanganob was apparently very desirous to have a garden at Ashkebwaka, for which I sent him a barrel of seed potatoes, corn, pumpkins, and a general assortment of seeds. Precisely what was done with the parcel I do not know, but none of it went into the ground. In most cases everything eatable went into their stomachs as soon as they were hungry. Even after potatoes had been planted, they have been dug out and eaten, and squashes when they were merely out of bloom. If the master of a lodge should be inclined to preserve the seed and a hungry brother came that way, their hospitality required that the garden should be sacrificed. Their motto is that the morrow will take care of itself. After being well fed, they are especially worthless. When corn has been issued to them to carry to their home, they have been known to throw it away and go off as happy as children.

Detail of the Saint Louis River with the Artichoke River (unlabeled) between the Knife Portage and East Savannah River from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

No footgear is more comfortable, especially in winter, than the moccasin. The Indian knows nothing of cold feet, though he has no shoes or even socks. His light loose moccasin is large enough to allow a wrap of one or more thickness of pieces of blankets, called “nepes.” In times of extreme cold, wisps of hay are put in around the “nepes.” In winter the snow is dry, and the rivers and swamps everywhere covered with ice, which is a thorough protection against wet feet. As they are never pinched by the devices of shoemakers, the blood circulates freely. The well tanned deer skin is soft and a good nonconductor, which cannot be said of the footgear of civilization. In summer the moccasin is light and easy to the foot, but is no protection against water. At night it is not dried at the camp-fire only wrung out to be put on wet in the morning. Like the bow and the arrow, these have nearly disappeared since Europeans have furnished bullets, powder and guns. Before that time the war club was a very important weapon. It was of wood, having a strong handle, with a ball or knot at the end. If the Chippewas used battleaxes of stone, they could not have been common. I have rarely seen a light war club with an iron spike well fastened in the knot or ball at the end. In ancient days, when their arrows and daggers were tipped with flint, their battles were like those of all rude people – personal encounters of the most desperate character. The sick are possessed of evil spirits which are driven out by incantations loud and prolonged enough to kill a well person. Their acquaintance with medical herbs is very complete.

One of the customs of the country is that of concubinage as well as polygamy, resembling in this respect the ancient Hebrews and other Eastern nations. The parents of a girl – on proper application and the payment of a blanket, some tobacco and other et ceteras, amounting to “ten pieces” – bestowing their daughter for such a period as her new master may choose. A further consideration is understood that she is to be clothed and fed, and when the parents visit the traders’ post they expect some pork and flour. To a maiden – who, as an Indian wife or in her father’s house is not only a drudge but a slave, compelled to row the canoe, to cut and bring wood, put up the lodge and take it down, and always to carry some burden – this situation is a very agreeable one. If she wishes to marry afterwards, her reputation does not suffer. While Mr. B. was conversing with the Hudson’s Bay man on the bank, some of the girls came coquettishly down to them frisking about in their rabbit skin blankets well saturated with grease. One of them managed to keep in view what she considered a special attraction – a fine pewter ring on her finger. These Chippewas damsels had in some way acquired the art of insinuation belonging to the sex without the aid of a boarding school.

The Indian agent at La Pointe killed a deer of about medium size, which he left in the woods. He engaged an Indian to bring it in. Night came and the next day before the man returned without the deer. “Where is my deer?” “Eat him, don’t suppose me to eat nothing.” Probably that meal lasted him a week. There is among them no regular time for meals or other occupations. If there are provisions in the lodge, each one helps himself; and if a visitor comes, he is offered what he can eat as long as it lasts. This is their view of hospitality. The lazy and worthless are never refused. To do this to the meanest professional dead beat would be the ruin of the character of the host.

Detail of portage between Lake Vermillion and the Saint Louis River headwaters from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

“Vincent Roy Sr. was born at Leech Lake Minn. in the year 1779 1797, and died at Superior, Wis. Feb. 18th 1872. He was a son of a Canadian Frenchman by the same name as his son bears. When V. Roy, Sr was about 17 or 18 years old, they emigrated to Fort Frances, Dominion of Canada, where he was engaged by the North-West Fur Co. as a trader until the two Companies (the North-West and the Hudson Bay Co joined together) he still worked for the consolidated Company for 12 or 15 years. When the American Traders came out at the Vermillion Lake country in Minnesota Three or four years afterwards he joined the American Traders. For several years he went to Mackinaw, buying goods and supplies for the Bois Fortes bands of Chippeways on Rainy and Vermillion Lake Country. About the year 1839 he came out to the Lake Superior Country and located his family at La Pointe. In winters he went out to Leech Lake Minn., trading for the American Fur Co. For several years until in the year of 1847 when the Hon. H. M. Rice, now of St. Paul, came to this country representing the Pierre Choteau Co. as a fur trading company. V. Roy, Sr. engaged to Pierre Choteau & Co. to trade with his former Indians at Vermillion Lake Country for two years, and then went for the American Fur Company again for one year. After a few years he engaged as a trader again for Peter E. Bradshaw & Co. and went to Red Lake, Minn. for several years. In 1861 he went to Nipigon (on Canadian side) trading for the same company. In a few years, he again went back to his old post at Vermillion Lake, Minn., where he contracted a very severe sickness, in two years afterwards he died at Superior among his Children as stated before &c.”

~ Minnesota Historical Society: Henry M. Rice and Family Papers, 1824-1966; Box 4; Sketches folder; Item “Roy, Vincent, 1797-1872”

Among the Chippewas we hear of man eaters, from the earliest travelers down to this day. Mr. Bushnell, formerly Indian agent at La Pointe, described one whom he saw who belonged on the St. Louis River and Vermillion Lake. The Indians have a superstitious dread of them, and will flee when one enters the lodge. They are hated, but it is supposed they cannot be killed, and no one ventures to make the experiment. it is only by a bullet such as the man eater himself shall designate that his body can be pierced. He is frequently a lunatic, spending days and nights alone in the woods in mid winter without food, traveling long spaces to present himself unexpectedly among distant bands. Whatever he chooses to eat is left for him, and right glad are the inmates of a lodge to get rid of him on such easy terms. The practice is not acquired from choice, but from the terrible necessities of hunger which happen every winter among the northern Indians. Like shipwrecked parties at sea, the weaker first falls a prey to the stronger, and their flesh goes to sustain life a little longer among the remainder. The Chippewas think that after one has tasted human food he has an uncontrollable longing for it, and that it is not safe to leave children alone with them. They say a man eater has red eyes and he looks upon the fat papoose with a demonical glance, and says: “How tender he would be.” One miserable object on the St. Louis River eat off his own lips, and finally became such a source of consternation that one Indian more courageous than the rest buried a tomahawk in his head. Another one who had the reputation of having killed all of his own family, came to the winter fishing ground on Rainy Lake, where Mr. Roy was trading with the Indians. He stayed on the ice trying to take some fish, but without success. Not one of the band dared go out to fish, although they were suffering from hunger. Mr. Roy and all the Indians requested him to go away, but he would not unless he had something to eat. no one but the trader could give him anything, and he was not inclined to do so. Things remained thus during three days, no squaw daring to go on the ice to fish for fear of the man eater. Mr. Roy urged them to kill him, but they said it would be of no use to shoot at him. The man eater dared them to fire. The trader at length lost patience with the cannibal and the terrified Bois Forts. He took his gun and warned the fellow that he would be shot if he remained on the ice. The faith of the savage appears to have been strong in the charm that surrounded his person, for he only replied by a laugh of derision. On the other side Mr. Roy had great faith in his rifle, and discharging it at the body of the man, he fell dead, as might have been expected. The Indians were at once relieved of a dreadful load, and sallied out to fish. No one, however, dared to touch the corpse.

No one of either party can go into the country of the other, and not be discovered. Their moccasins differ and their mode of walking. Their canoes and paddles are not alike, and their camp-fires as well as their lodges differ. The Chippewa lodge or wigwam is made by a circular or oblong row of small poles set in the ground, bending the tops over and fastening them with bark. They carry everywhere rolls of birch bark, which unroll like a carpet. These are wound on the poles next the ground course, and overlapping this a second and third, so as to shed rain. On one side is a low opening covered by a blanket, and at the top a circular place for the smoke to escape. The fire is on the ground at the centre. The work of putting up the lodge is done by the squaws, who gather wood for the fire, spread the mats, and proceed to cook their meals, provided there is anything to cook.

Stereograph of “Chippewa Indians and Wigwams” by Martin’s Art Gallery, circa 1862-1875, shows that they used more than one type of wigwam.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

A Sioux lodge is the model of the Sibley tent, with a pole at the centre and others set around in a circle, leaning against the central one at the top, forming a cone. This they cover with skins of the buffalo, deer, elk or moose, wound around like the Chippewa rolls of bark, leaving a space at the top for the smoke to escape, and an entrance at the side. This is stronger and more compact than the Chippewa wigwam, and withstands the fiercest storms of the prairies. In winter, earth is occasionally piled around the base, which makes it firmer and warmer.

We were coming down the Rum River, late in the fall of 1848, when one of our voyageurs discovered the track of a Sioux in the sand. It was at least three weeks old, but nothing could induce him to stay with us, not even an hour. He was not sure but a mortal enemy was then tracking us for the purpose of killing him.

Detail of Red Lake from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

Earlier in the season we were at Red Lake. A cloud of smoke came up from the west, which caused a commotion in the village and mission at the south end of the lake. A war party was then out on a Sioux raid. The chief had lost a son, killed by them. He had managed to get the hand of a Sioux, which he had planted at the head of his son’s grave. But this did not satisfy his revenge nor appease the spirit of his son. He organized a war party to get more scalps, which was then out. A warrior chief or medicine man gains his principal control of the warriors by means of a prophecy, which he must make in detail. If the first of his predictions should fail, the party may desert him entirely. In this case, on a certain day they would meet a bear. When they met the enemy, if they were to be victorious, a cloud of smoke would obscure the sun. It was this darkening of the sky that excited the hopes of the Red Lake band. They were sure there had been a battle and that the Sioux were defeated.

Judge Samuel Ashmun

~ Chippewa County Historical Society

The late Judge Ashmun, of Sault Ste. Marie, while he was a minor, wandered off from his nativity in Vermont to Lake Superior, through it to Fond du Lac, and thence by way of the St. Louis River to Sandy Lake on the Mississippi. Somewhere in that region he was put in charge of one of Astor’s trading posts. In the early winter of 1818 he went on a hunt with a party of seventeen indiscreet young braves, against the advice of the sachems, apparently in a southwesterly direction on the Sioux border, or neutral land. Far from being neutral, it was very bloody ground. At the end of the third day they were about fifty miles from the post. On the morning of each day a rendezvous was fixed upon for the next camp. Each one then commenced the hunt for the day, taking what route pleased himself. The ice on the lakes and marshes was strong and the snow not uncomfortably deep. The principal game was deer, with some pheasants, prairie hens, rabbits and porcupines. What a hunter could not carry he hung upon trees to be carried home upon their return. Their last camp was on the border of a lake in thick woods, with tall dry grass on the margin of the lake. Having killed all the deer they could carry, it was determined to begin the return march the next day. It was not a war party, but they were prepared for their Sioux enemies, of whom no signs had been discerned. There was no whiskey in the camp, but when the stomach of an Indian is filled to its enormous capacity with fresh venison he is always jolly. It was too numerous a party to shelter themselves by a roof of boughs over the fire, but they had made a screen against the wind of branches of pine, hemlock or balsam. Around the fire was a circle of boughs on which they sat, ate and slept. Some were mending their moccasins, other smoking tobacco and kinnikinic, playing practical jokes, telling stories, singing songs and gambling. Mr. Ashmun could get so little sleep that he took Wa-ne-jo, who had a boy of thirteen years, and they made a separate camp. This man going to the lake to drink, was certain that he heard the tramp and felt the vibrations of a party going over the ice, who could be no other than the Sioux. He returned, and after some hesitation Mr. Ashmun reported the news to the main camp. “Oh, Wa-ne-jo is a liar, nobody believes him,” was the universal response. Mr. Ashmun, however, gave credit to the repot. They immediately put out the fire at his bivouac. Even war parties do not place sentinels, because attacks are never made until break of day. In the isolated camp they waited impatiently for the first glimpse of morning. Most of the other party fell asleep with a feeling of security, for which they took no steps to verify. One of them lay down without his moccasins. Mr. Ashmun and his man were just ready to jump for the tall grass when a volley was poured into the other camp, accompanied by the usual savage yell. The darkness and stillness of a faint morning twilight made this burst of war still more terrific. Taking the boy between them, they commenced the race for life under the guidance of Wa-ne-jo, in a direction directly opposite to their home. He well knew the Sioux all night long had been creeping stealthily over the snow and through the thicket, and had formed a line behind the main camp. The Chippewas made a brave defence, giving back their howls of defiance and fighting as they dispersed through the woods. Eight were killed near the camp and a wounded one at some distance, where he had secreted himself. Two fo the wounded were helped away according to custom, and also the barefooted man, whose feet were soon frozen. All clung to their guns, and the frightened boy to his hatchet. They estimated the Sioux party to have been one hundred and thirty, of whom they killed four and wounded seven, but brought in no scalps.

Indians Canoeing in the Rapids painting by Cornelius Krieghoff, 1856.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

In his way, the Chippewa is quite religious. He believes in a future world where there is a happy place for good Indians. If he is paddling his canoe against a head wind and can afford it, he throws overboard a piece of tobacco, the most precious thing he has. With this offering there is a short invocation to the good manitou for a fair breeze, when he can raise a blanket for a sail, stop rowing and take a smoke. At the head of many a rapid which it is dangerous to run, are seen pieces of tobacco on the rocks, which were laid there with a brief prayer that they may go safely through. Some of them, which are frightful to white men, they pass habitually. These offerings are never disturbed, for they are sacred. He endeavors also to appease the evil spirit Nonibojan. Fire, rocks, waterfalls, mountains and animals are alive with spirits good and bad. The medicine man, who is prophet, physician, priest and warrior, is an object of reverence and admiration. His prayers are for success in the hunt, accompanied by incantations.

George Bonga

~ Wikipedia.org

Among the stories of a thousand camp-fires, was one by Charlie, a stalwart, half-breed Indian and negro, whose father was an escaped slave. On the shores of Sandy Lake, a party of Chippewas had crossed on the ice in midwinter, and encamped in the woods not far from the north shore. One of them went to the Lake with a kettle of water, and a hatchet to cut the ice. After he filled his kettle, he lay down to drink. The water was not entirely quiet, which attracted his attention at once. His suspicions were aroused, and placing his ear to the ice, he discerned regular pulsations, which his wits, sharpened by close attention to every sight and every sound, interpreted to be the tramp of men. They could be no other than Sioux, and there must be a party larger than their own. Their fire was instantly put out, and they separated to meet at daylight at a place several miles distant. All their conclusions were right. One band of savages outwitted another, having instincts of danger that civilized men would have allowed to pass unnoticed. The Sioux found only the embers of a deserted camp, and saw the tracks of their enemies diverge in so many directions that it was useless to pursue.

In 1839 the Chippewas on the upper Mississippi were required to come to Fort Snelling to receive their payments. That post was in Sioux territory, and the order gave offense to both nations. It required the presence of the United States troops to prevent murders even on the reservation. On the way home at Sunrise River, the Chippewas were surprised by a large force of Sioux, and one hundred and thirty-six were killed.

At the mouth of Crow Wing River, on the east bank of the Mississippi, is a ridge of gravel, on which there were shallow pits. The Indians said that, about fifteen years before, a war party of Sioux was above there on the river to attack the Sandy Lake band. A party of Chippewas concealed themselves in these pits, awaiting the descent of their enemies. The affair was so well managed that the surprise was complete. When the uncautious Sioux floated along within close range of their guns, the Chippewa warriors rose and delivered their fire into the canoes. Some got ashore and escaped through the woods to the westward, but a large portion were killed.

Detail of Crow Wing River from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

While crossing the Elk River, between the falls of St. Anthony and those of St. Cloud, a squaw ran into the water, screaming furiously, followed by a man with a club. This was her lord and master, bent on giving her a taste of discipline very common in Indian life. She succeeded in escaping this time by going into deep water. Her nose had been disfigured by cutting away most of the fleshy portions, as a punishment for unfaithfulness to a husband, who was probably worse than herself.

At the mouth of Crow Wing River was an Indian skipping about with the skin of a skunk tied to one of his ankles. There was also in a camp near the post another Chippewa, who had murdered a brother of the lively man. There is no criminal law among them but that of retaliation. Any member of the family may execute this law at such time and manner as he shall decide. This badge of skunk’s skin was a notice to the murderer that the avenger was about, and that his mission was not fulfilled. Once the guilty man had been shot through the thigh, as a foretaste of what was to follow. The avenger seemed to enjoy badgering his enemy, whom he informed that although he might be occasionally wounded, it was not the intention at present to kill him outright. If the victim should kill his persecutor, he well knew that some other relative would have executed full retaliation.

~ The Assassination of Hole In The Day [the Younger] by Anton Treuer, 2010.

Hole In The Day the Younger

aka Kue-wee-sas (Gwiiwizens [Boy or Lad])

(1825-1868)

Bagone-giizhig the Younger

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

This Chippewa brave, Bug-on-a-ke-dit, lived on a knoll overlooking the Mississippi River, four miles above Little Rock, where he had a garden. He appeared at the payment at La Pointe, in 1848, with a breech cloth and scanty leggings. This was partially for showing off a very perfect figure, tall, round and lithe, the Apollo of the woods. His scanty dress enabled him to exhibit his trophies in war. The dried ears of his foes, a part of whom were women, were suspended at his neck. Around his tawny arms were bright brass bands, but there was nothing of which he was more proud than a bullet hole just below the right breast. The place of the wound was painted black, and around it circles of red, yellow and purple; other marks on the chest, arms and face told of the numbers he had slain and scalped, in characters well understood by all Chippewas. The numbers of eagle feathers in his hair informed the savage crowd how many battles he had fought. He was not, like Grizzly Bear, a great orator, but resembled him in getting drunk at every opportunity. He managed to procure a barrel of whiskey, which he carried to his lodge. While it was being unloaded it fell upon and crushed him to death. Looking up a grass clad hill, a dingy flag was seen (1848) fluttering on a pole where he was buried. He often repeated with great zest the mode by which the owners of two of the desecrated ears were killed. His party of four braves discovered some Sioux lodges on the St. Peters, from which all the men were absent. The squaws lodged their hereditary enemies over night with their accustomed hospitality. Bug-on-a-ke-dit and his party concealed themselves during the day, and at dark each one attacked a lodge. Seven women and children were slaughtered. His son Kue-wee-sas, or Po-go-noy-ke-schik, was a much more respectable and influential chief.

An hundred years since, the Sioux had an extensive burial ground, on the outlet of Sandy Lake, a few miles east of the Mississippi River. Their dead were encased in bark coffins and placed on scaffolds supported by four cedar posts, five or six feet high. This was done to prevent wolves from destroying the bodies. Thirty years since some of these coffins were standing in a perfect condition, but most of them were broken or wholly fallen, only the posts standing well whitened by age. The Chippewas wrap the corpse in a blanket and a roll of birch bark, and dig a shallow grave in which the dead are laid. A warrior is entitled to have his bow and arrow, sometimes a gun and and a kettle, laid beside him with his trinkets. Over the mound a roof of cedar bark is firmly set up, and the whole fenced with logs or protected in some way against wolves and other wild animals. There is a hole at one or both ends of the bark shelter, in which is friends place various kinds of food. Their belief in a spirit world hereafter is universal. If it is a hunter or warrior, he will need his arms to kill game or to slay his enemies. Their theory is that the dog may go to the spiritual country, as a spirit, also his weapons, and the food which is provided for the journey. To him every thing has its spiritual as well as its material existence. Over all is the great spirit or kitchi-manitou, looking after the happiness of his children here and hereafter.

Stephen Bonga

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Winter travelling in those northern regions is by no means so uncomfortable as white men imagine. By means of snow shoes the Indian can move in a straight course towards his village, without regard to the trail. In the short days of winter he starts at day break and travels util dark. Stephen said he made fifty miles a day in that way, which is more than he could have done in summer.

At night they endeavor to find a thicket where there is a screen against the wind and plenty of wood. They scoop away the snow with their shoes and start a fire at the bottom of the pit. Around this they spread branches of pine, balsam or cedar, and over head make a shelter of brush to keep off the falling snow. Probably they have a team or more of dogs harnessed to sledges, who take their places around the fire. Here they cook and eat an enormous meal, when they wrap themselves in blankets for a profound sleep. Long before day another heavy meal is eaten. Everything is put in its proper package ready to start as soon as there is light enough to keep their course.

– Freelang Ojibwe-English by Weshki-ayaad, Charles Lippert and Guy T. Gambill

– Ojibwe People’s Dictionary by the Department of American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota

Many Indian words have originated since the white people came among them. A large proportion of their proper names are very apt expressions of something connected with the person, lake, river, or mountain to which they are applied. This people, in their primitive state, knew nothing of alcohol, coffee, tea, fire-arms, money, iron, and hundreds of other things to which they gave names, generally very appropriate ones. A negro is black meat; coffee is black medicine drink; tea, red medicine drink; iron, black metal; gold, yellow metal. I was taking the altitude of the sun at noon near Red Lake Mission with a crowd of Chippewas standing around greatly interested. They had not seen the liquid metal mercury, used for an artificial horizon in such observations, which excited their especial astonishment, and they had no name for it. One of them said something which caused a general expression of delight, for which I enquired the reason. He had coined a word for mercury on the spot, which means silver water.

Detail of Minnesota Point during George Stuntz’s survey contract during August-October of 1852.

~ Barber Papers (prologue): Stuntz Surveys Superior City 1852-1854

This family’s sugar bush was located at or near Silver Creek (T53N-R10W).

~ General Land Office Records

Indian trail to Rockland townsite overlooking English/Mineral Lake and Gogebic Iron Range.

~ Penokee Survey Incidents: Number V

Coasting along the beach northward from the mouth of the St. Louis River, on Minnesota Point, I saw a remarkable mark in the sand and went ashore to examine it. The heel and after part was clearly human. At the toes there was a cleft like the letter V and on each side some had one, others two human toes. Not far distant were Indians picking berries under the pine trees, which then covered the point in its entire length. We asked the berrypickers what made those tracks. They smiled and offered to sell us berries, of which they had several bushels, some in mokoks of birch bark, others in their greasy blankets. An old man had taken off his shirt, tied the neck and arms, and filled it half full of huckleberries. By purchasing some, (not from the shirt or blanket) we obtained an explanation of the nondescript tracks. There was a large family, all girls, whose feet were deformed in that manner. It was as though their feet had been split open when young halfway to the instep, and some of the toes lost. They had that spring met with a great loss by the remorseless bear. On the north shore, thirty miles east of Duluth, they had a fine sugar orchard, and had made an unusual quantity of sugar. A part was brought away, and a part was stored high up in trees in mokoks. There is nothing more tempting than sugar and whiskey to a bear. When this hard working family returned for their sugar and dried apples, moistened with whiskey, to lure bruin on to his ruin. A trap fixed with a heavy log is set up across a pen of logs, in the back end of which this bait is left, very firmly tied between two pieces of wood. This is fastened to a wooden deadfall, supporting one end of a long piece of round timber that has another piece under it. The bear smells the bait from afar, goes recklessly into the pen, and commences to gnaw the pieces of wood; before he gets much of the bait the upper log falls across his back, crushing him upon the lower one, where, if he is not killed, his hind legs are paralyzed. These deadly pens are found everywhere in the western forests. Two bears ranging along the south shore of English Lake, in Ashland County, Wisconsin, discovered some kegs of whiskey which contraband dealers had concealed there. With blows from their heavy paws they broke in the heads of the kegs and licked up the contents. They were soon in a very maudlin state, rolling about on the ground, embracing each other in an affectionate manner and vainly trying to go up the trees. Before the debauch was ended they were easily captured by a party of half-breeds. There are Indians who acknowledge the bear to be a relation, and profess a dislike to kill them. When they do they apologize, and say they do it because they are “buckoda,” or because it is necessary.

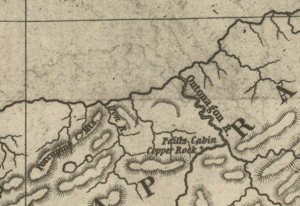

Detail of the Porcupine Mountains between the Montreal River and Ontonagon River from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

At Ontonagon, a very sorry looking young Indian came out of a lodge on the west side of the river and expressed a desire to take passage in our boat. There had been a great drunk in that lodge the day before. The squaws were making soup of the heads of white fish thrown away by the white fishermen. Some of the men were up, others oblivious to everything. Our passenger did not become thoroughly sober until towards evening. We passed the Lone Rock and encamped abreast of the Porcupine Mountains. Here he recovered his appetite. The next day, near the Montreal River, a squaw was seen launching her canoe and steering for us. She accosted the young fellow, demanding a keg of whiskey. He said nothing. She had given him furs enough to purchase a couple of gallons and he had made the purchase, but between himself and his friends it had completely disappeared. The old hag was also fond of whiskey. The fraud and disappointment put her into a rage that was absolutely fiendish. Her haggard face, long, coarse, greasy, black hair, voluble tongue and shrill voice perfected that character.

Turning into the mouth of the river we found a party from Lake Flambeau fishing in the pool at the foot of the Great Fall. Their success had not been good, and of course they were hungry. One of our men spilled some flour on the sand, of which he could save but little. The Flambeaus were delighted, and, gathering up sand and flour together, put the mixture in their kettle. The sand settled at the bottom, and the flour formed an excellent porridge for hungry aboriginees.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

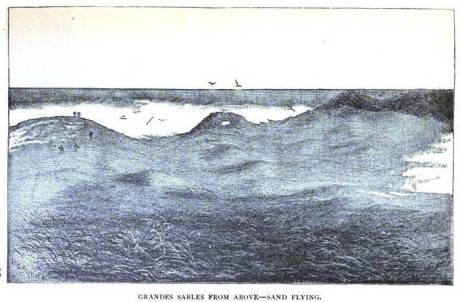

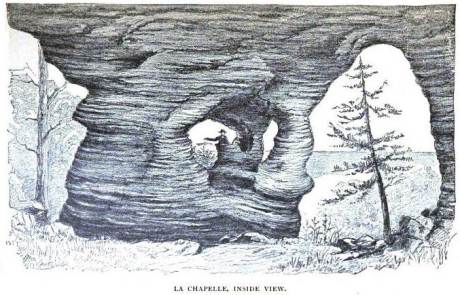

Mushinnewa and Waubannika, Chippewas, lived at Bad River, near Odana. Mushinnewa had a very bad reputation among his tribe. He was not only quarrelsome when drunk, but was not peaceable when sober. He broke Waubannika’s canoe into fragments, which was resented by the wife of the latter on the spot. She made use of the awl with which she was sewing the bark on another canoe, as a weapon, and stabbed old Mushinnewa in several places so severely that it was thought he would die. He threatened to kill her, and she fled with her husband to Lake Flambeau. But Mushinnewa did not die. He had a son as little liked by the Odana band as himself. In a drunken affray at Ontonagon another Indian killed him. The murderer then took the body in his canoe, brought it to Bad River and delivered it to old Mushinnewa. According to custom the Indian handed the enraged father the knife with which his son was killed, and baring his breast told him to strike. The villagers were happy to be rid of the young villain, and took the knife from the hand of his legal avenger. A barrel of flour covered the body, and before night Mushinnewa adopted the Indian as his son.