Among The Otchipwees: II

June 4, 2016

By Amorin Mello

… continued from Among The Otchipwees: I

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 3 January 1885

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 177-192.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

II.

In the fall of 1849, the Bad Water band were in excellent condition, and therefore very happy. Deer were then very abundant on the Menominee. They are nimble animals, able to leap gracefully over obstructions as high as a man’s head standing. But they do not like such efforts, unless there is a necessity for it. The Indians discovered this long ago, and built long brush fences across their trails to the water. When the unsuspecting animal has finished browsing, he goes for a drink with the regularity of an habitué of a saloon. Seeing the obstruction, he walks leisurely along it, expecting to find a low place, or the end of it. The dark eye of the Chippewa is fixed upon him from the top of a tree. This is much the best position, because the deer is not likely to look up, and the wind is less likely to bear his odor to the delicate nostrils of the game. At such close quarters every shot is fatal. Its throat is cut, its legs tied together, and thrown over the head and shoulders of the hunter, its body resting on his back, and he starts for the village. Here the squaws strip off the hide and prepare the carcass for the kettle. With a tin cup full of flour or a pound of pork, we often purchased a saddle of venison, and both parties were satisfied with the trade.

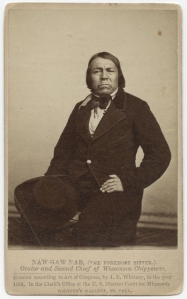

Naagaanab

~ Minnesota Historical Society

~ Executive Documents of the State of Minnesota for the Year 1886, Volume V.: Minnesota Geographical Names Derived from the Chippewa Language, by Reverend Joseph Alexander Gilfillan, 1887, page 457.

“Akwaakwaa” refers to “go a certain distance in the woods.”

~ General Geology: Miscellaneous Papers, Volume 1: A Report of Explorations in the Mineral Regions of Minnesota During the Years 1848, 1859 and 1864 by Colonel Charles Whittlesey, 1866, page 44.

Of course the man of the woods has a preference as to what he shall eat; but when he is suffering from hunger, as he is a large part of his days, he is not very particular. Fresh venison, bear meat, buffalo, moose, caribou, porcupine, wild geese, ducks, rabbits, pigeons, or fish, relish better than gulls, foxes, or skunks. The latter do very well while he is on the verge of starvation, and even owls, crows, dead horses and oxen. The lakes of the interior of Minnesota and Wisconsin produce wild rice spontaneously. When parched it is more palatable than southern rice, and more nutritious. Potatoes grow well everywhere in the north country; varieties of corn ripen as far north as Red Lake. Nothing but a disinclination to labor hinders the Chippewa from always having enough to eat. With the wild rice, sugar, and the fat of animals, well mixed, they make excellent rations, which will sustain life longer than any preparation known to white men. A packer will carry on his back enough to last him forty days. He needs only a tin cup in which to warm water, with which it makes a rich soup. Pemmican is less palatable, and sooner becomes rancid. This is made of smoke or jerked meat pulverized, saturated with fat and pressed into cakes or blocks. Sturgeon are numerous and large, and when well smoked and well pulverized they furnish palatable food even without salt, and keep indefinitely. Voyagers mix it with sugar and water in their cups. In the large lakes, white fish, siskowit, and lake trout are abundant. In the smaller lakes and rivers there are many varieties of fish. With so many resources supplied by nature, if the natives suffer from hunger it is solely caused by indolence. His implicit reliance upon the Great Spirit, which is his good Providence, no doubt encourages improvidence. Nanganob was apparently very desirous to have a garden at Ashkebwaka, for which I sent him a barrel of seed potatoes, corn, pumpkins, and a general assortment of seeds. Precisely what was done with the parcel I do not know, but none of it went into the ground. In most cases everything eatable went into their stomachs as soon as they were hungry. Even after potatoes had been planted, they have been dug out and eaten, and squashes when they were merely out of bloom. If the master of a lodge should be inclined to preserve the seed and a hungry brother came that way, their hospitality required that the garden should be sacrificed. Their motto is that the morrow will take care of itself. After being well fed, they are especially worthless. When corn has been issued to them to carry to their home, they have been known to throw it away and go off as happy as children.

Detail of the Saint Louis River with the Artichoke River (unlabeled) between the Knife Portage and East Savannah River from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

No footgear is more comfortable, especially in winter, than the moccasin. The Indian knows nothing of cold feet, though he has no shoes or even socks. His light loose moccasin is large enough to allow a wrap of one or more thickness of pieces of blankets, called “nepes.” In times of extreme cold, wisps of hay are put in around the “nepes.” In winter the snow is dry, and the rivers and swamps everywhere covered with ice, which is a thorough protection against wet feet. As they are never pinched by the devices of shoemakers, the blood circulates freely. The well tanned deer skin is soft and a good nonconductor, which cannot be said of the footgear of civilization. In summer the moccasin is light and easy to the foot, but is no protection against water. At night it is not dried at the camp-fire only wrung out to be put on wet in the morning. Like the bow and the arrow, these have nearly disappeared since Europeans have furnished bullets, powder and guns. Before that time the war club was a very important weapon. It was of wood, having a strong handle, with a ball or knot at the end. If the Chippewas used battleaxes of stone, they could not have been common. I have rarely seen a light war club with an iron spike well fastened in the knot or ball at the end. In ancient days, when their arrows and daggers were tipped with flint, their battles were like those of all rude people – personal encounters of the most desperate character. The sick are possessed of evil spirits which are driven out by incantations loud and prolonged enough to kill a well person. Their acquaintance with medical herbs is very complete.

One of the customs of the country is that of concubinage as well as polygamy, resembling in this respect the ancient Hebrews and other Eastern nations. The parents of a girl – on proper application and the payment of a blanket, some tobacco and other et ceteras, amounting to “ten pieces” – bestowing their daughter for such a period as her new master may choose. A further consideration is understood that she is to be clothed and fed, and when the parents visit the traders’ post they expect some pork and flour. To a maiden – who, as an Indian wife or in her father’s house is not only a drudge but a slave, compelled to row the canoe, to cut and bring wood, put up the lodge and take it down, and always to carry some burden – this situation is a very agreeable one. If she wishes to marry afterwards, her reputation does not suffer. While Mr. B. was conversing with the Hudson’s Bay man on the bank, some of the girls came coquettishly down to them frisking about in their rabbit skin blankets well saturated with grease. One of them managed to keep in view what she considered a special attraction – a fine pewter ring on her finger. These Chippewas damsels had in some way acquired the art of insinuation belonging to the sex without the aid of a boarding school.

The Indian agent at La Pointe killed a deer of about medium size, which he left in the woods. He engaged an Indian to bring it in. Night came and the next day before the man returned without the deer. “Where is my deer?” “Eat him, don’t suppose me to eat nothing.” Probably that meal lasted him a week. There is among them no regular time for meals or other occupations. If there are provisions in the lodge, each one helps himself; and if a visitor comes, he is offered what he can eat as long as it lasts. This is their view of hospitality. The lazy and worthless are never refused. To do this to the meanest professional dead beat would be the ruin of the character of the host.

Detail of portage between Lake Vermillion and the Saint Louis River headwaters from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

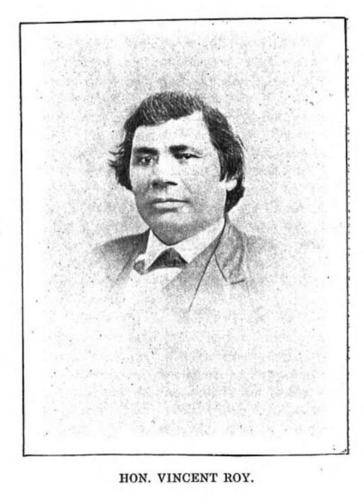

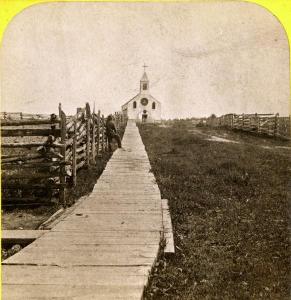

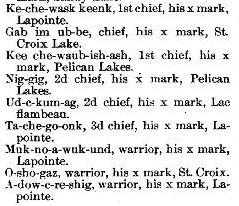

“Vincent Roy Sr. was born at Leech Lake Minn. in the year 1779 1797, and died at Superior, Wis. Feb. 18th 1872. He was a son of a Canadian Frenchman by the same name as his son bears. When V. Roy, Sr was about 17 or 18 years old, they emigrated to Fort Frances, Dominion of Canada, where he was engaged by the North-West Fur Co. as a trader until the two Companies (the North-West and the Hudson Bay Co joined together) he still worked for the consolidated Company for 12 or 15 years. When the American Traders came out at the Vermillion Lake country in Minnesota Three or four years afterwards he joined the American Traders. For several years he went to Mackinaw, buying goods and supplies for the Bois Fortes bands of Chippeways on Rainy and Vermillion Lake Country. About the year 1839 he came out to the Lake Superior Country and located his family at La Pointe. In winters he went out to Leech Lake Minn., trading for the American Fur Co. For several years until in the year of 1847 when the Hon. H. M. Rice, now of St. Paul, came to this country representing the Pierre Choteau Co. as a fur trading company. V. Roy, Sr. engaged to Pierre Choteau & Co. to trade with his former Indians at Vermillion Lake Country for two years, and then went for the American Fur Company again for one year. After a few years he engaged as a trader again for Peter E. Bradshaw & Co. and went to Red Lake, Minn. for several years. In 1861 he went to Nipigon (on Canadian side) trading for the same company. In a few years, he again went back to his old post at Vermillion Lake, Minn., where he contracted a very severe sickness, in two years afterwards he died at Superior among his Children as stated before &c.”

~ Minnesota Historical Society: Henry M. Rice and Family Papers, 1824-1966; Box 4; Sketches folder; Item “Roy, Vincent, 1797-1872”

Among the Chippewas we hear of man eaters, from the earliest travelers down to this day. Mr. Bushnell, formerly Indian agent at La Pointe, described one whom he saw who belonged on the St. Louis River and Vermillion Lake. The Indians have a superstitious dread of them, and will flee when one enters the lodge. They are hated, but it is supposed they cannot be killed, and no one ventures to make the experiment. it is only by a bullet such as the man eater himself shall designate that his body can be pierced. He is frequently a lunatic, spending days and nights alone in the woods in mid winter without food, traveling long spaces to present himself unexpectedly among distant bands. Whatever he chooses to eat is left for him, and right glad are the inmates of a lodge to get rid of him on such easy terms. The practice is not acquired from choice, but from the terrible necessities of hunger which happen every winter among the northern Indians. Like shipwrecked parties at sea, the weaker first falls a prey to the stronger, and their flesh goes to sustain life a little longer among the remainder. The Chippewas think that after one has tasted human food he has an uncontrollable longing for it, and that it is not safe to leave children alone with them. They say a man eater has red eyes and he looks upon the fat papoose with a demonical glance, and says: “How tender he would be.” One miserable object on the St. Louis River eat off his own lips, and finally became such a source of consternation that one Indian more courageous than the rest buried a tomahawk in his head. Another one who had the reputation of having killed all of his own family, came to the winter fishing ground on Rainy Lake, where Mr. Roy was trading with the Indians. He stayed on the ice trying to take some fish, but without success. Not one of the band dared go out to fish, although they were suffering from hunger. Mr. Roy and all the Indians requested him to go away, but he would not unless he had something to eat. no one but the trader could give him anything, and he was not inclined to do so. Things remained thus during three days, no squaw daring to go on the ice to fish for fear of the man eater. Mr. Roy urged them to kill him, but they said it would be of no use to shoot at him. The man eater dared them to fire. The trader at length lost patience with the cannibal and the terrified Bois Forts. He took his gun and warned the fellow that he would be shot if he remained on the ice. The faith of the savage appears to have been strong in the charm that surrounded his person, for he only replied by a laugh of derision. On the other side Mr. Roy had great faith in his rifle, and discharging it at the body of the man, he fell dead, as might have been expected. The Indians were at once relieved of a dreadful load, and sallied out to fish. No one, however, dared to touch the corpse.

No one of either party can go into the country of the other, and not be discovered. Their moccasins differ and their mode of walking. Their canoes and paddles are not alike, and their camp-fires as well as their lodges differ. The Chippewa lodge or wigwam is made by a circular or oblong row of small poles set in the ground, bending the tops over and fastening them with bark. They carry everywhere rolls of birch bark, which unroll like a carpet. These are wound on the poles next the ground course, and overlapping this a second and third, so as to shed rain. On one side is a low opening covered by a blanket, and at the top a circular place for the smoke to escape. The fire is on the ground at the centre. The work of putting up the lodge is done by the squaws, who gather wood for the fire, spread the mats, and proceed to cook their meals, provided there is anything to cook.

Stereograph of “Chippewa Indians and Wigwams” by Martin’s Art Gallery, circa 1862-1875, shows that they used more than one type of wigwam.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

A Sioux lodge is the model of the Sibley tent, with a pole at the centre and others set around in a circle, leaning against the central one at the top, forming a cone. This they cover with skins of the buffalo, deer, elk or moose, wound around like the Chippewa rolls of bark, leaving a space at the top for the smoke to escape, and an entrance at the side. This is stronger and more compact than the Chippewa wigwam, and withstands the fiercest storms of the prairies. In winter, earth is occasionally piled around the base, which makes it firmer and warmer.

We were coming down the Rum River, late in the fall of 1848, when one of our voyageurs discovered the track of a Sioux in the sand. It was at least three weeks old, but nothing could induce him to stay with us, not even an hour. He was not sure but a mortal enemy was then tracking us for the purpose of killing him.

Detail of Red Lake from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

Earlier in the season we were at Red Lake. A cloud of smoke came up from the west, which caused a commotion in the village and mission at the south end of the lake. A war party was then out on a Sioux raid. The chief had lost a son, killed by them. He had managed to get the hand of a Sioux, which he had planted at the head of his son’s grave. But this did not satisfy his revenge nor appease the spirit of his son. He organized a war party to get more scalps, which was then out. A warrior chief or medicine man gains his principal control of the warriors by means of a prophecy, which he must make in detail. If the first of his predictions should fail, the party may desert him entirely. In this case, on a certain day they would meet a bear. When they met the enemy, if they were to be victorious, a cloud of smoke would obscure the sun. It was this darkening of the sky that excited the hopes of the Red Lake band. They were sure there had been a battle and that the Sioux were defeated.

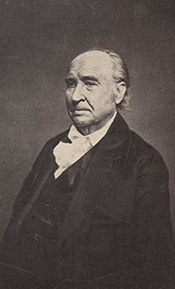

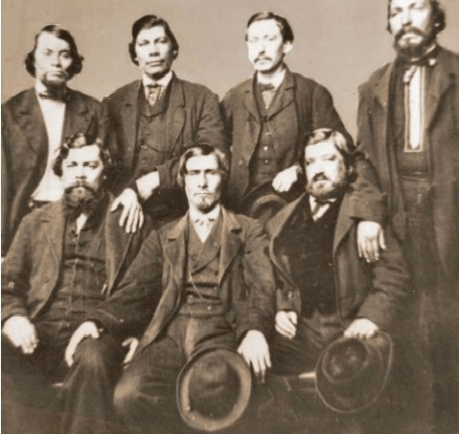

Judge Samuel Ashmun

~ Chippewa County Historical Society

The late Judge Ashmun, of Sault Ste. Marie, while he was a minor, wandered off from his nativity in Vermont to Lake Superior, through it to Fond du Lac, and thence by way of the St. Louis River to Sandy Lake on the Mississippi. Somewhere in that region he was put in charge of one of Astor’s trading posts. In the early winter of 1818 he went on a hunt with a party of seventeen indiscreet young braves, against the advice of the sachems, apparently in a southwesterly direction on the Sioux border, or neutral land. Far from being neutral, it was very bloody ground. At the end of the third day they were about fifty miles from the post. On the morning of each day a rendezvous was fixed upon for the next camp. Each one then commenced the hunt for the day, taking what route pleased himself. The ice on the lakes and marshes was strong and the snow not uncomfortably deep. The principal game was deer, with some pheasants, prairie hens, rabbits and porcupines. What a hunter could not carry he hung upon trees to be carried home upon their return. Their last camp was on the border of a lake in thick woods, with tall dry grass on the margin of the lake. Having killed all the deer they could carry, it was determined to begin the return march the next day. It was not a war party, but they were prepared for their Sioux enemies, of whom no signs had been discerned. There was no whiskey in the camp, but when the stomach of an Indian is filled to its enormous capacity with fresh venison he is always jolly. It was too numerous a party to shelter themselves by a roof of boughs over the fire, but they had made a screen against the wind of branches of pine, hemlock or balsam. Around the fire was a circle of boughs on which they sat, ate and slept. Some were mending their moccasins, other smoking tobacco and kinnikinic, playing practical jokes, telling stories, singing songs and gambling. Mr. Ashmun could get so little sleep that he took Wa-ne-jo, who had a boy of thirteen years, and they made a separate camp. This man going to the lake to drink, was certain that he heard the tramp and felt the vibrations of a party going over the ice, who could be no other than the Sioux. He returned, and after some hesitation Mr. Ashmun reported the news to the main camp. “Oh, Wa-ne-jo is a liar, nobody believes him,” was the universal response. Mr. Ashmun, however, gave credit to the repot. They immediately put out the fire at his bivouac. Even war parties do not place sentinels, because attacks are never made until break of day. In the isolated camp they waited impatiently for the first glimpse of morning. Most of the other party fell asleep with a feeling of security, for which they took no steps to verify. One of them lay down without his moccasins. Mr. Ashmun and his man were just ready to jump for the tall grass when a volley was poured into the other camp, accompanied by the usual savage yell. The darkness and stillness of a faint morning twilight made this burst of war still more terrific. Taking the boy between them, they commenced the race for life under the guidance of Wa-ne-jo, in a direction directly opposite to their home. He well knew the Sioux all night long had been creeping stealthily over the snow and through the thicket, and had formed a line behind the main camp. The Chippewas made a brave defence, giving back their howls of defiance and fighting as they dispersed through the woods. Eight were killed near the camp and a wounded one at some distance, where he had secreted himself. Two fo the wounded were helped away according to custom, and also the barefooted man, whose feet were soon frozen. All clung to their guns, and the frightened boy to his hatchet. They estimated the Sioux party to have been one hundred and thirty, of whom they killed four and wounded seven, but brought in no scalps.

Indians Canoeing in the Rapids painting by Cornelius Krieghoff, 1856.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

In his way, the Chippewa is quite religious. He believes in a future world where there is a happy place for good Indians. If he is paddling his canoe against a head wind and can afford it, he throws overboard a piece of tobacco, the most precious thing he has. With this offering there is a short invocation to the good manitou for a fair breeze, when he can raise a blanket for a sail, stop rowing and take a smoke. At the head of many a rapid which it is dangerous to run, are seen pieces of tobacco on the rocks, which were laid there with a brief prayer that they may go safely through. Some of them, which are frightful to white men, they pass habitually. These offerings are never disturbed, for they are sacred. He endeavors also to appease the evil spirit Nonibojan. Fire, rocks, waterfalls, mountains and animals are alive with spirits good and bad. The medicine man, who is prophet, physician, priest and warrior, is an object of reverence and admiration. His prayers are for success in the hunt, accompanied by incantations.

George Bonga

~ Wikipedia.org

Among the stories of a thousand camp-fires, was one by Charlie, a stalwart, half-breed Indian and negro, whose father was an escaped slave. On the shores of Sandy Lake, a party of Chippewas had crossed on the ice in midwinter, and encamped in the woods not far from the north shore. One of them went to the Lake with a kettle of water, and a hatchet to cut the ice. After he filled his kettle, he lay down to drink. The water was not entirely quiet, which attracted his attention at once. His suspicions were aroused, and placing his ear to the ice, he discerned regular pulsations, which his wits, sharpened by close attention to every sight and every sound, interpreted to be the tramp of men. They could be no other than Sioux, and there must be a party larger than their own. Their fire was instantly put out, and they separated to meet at daylight at a place several miles distant. All their conclusions were right. One band of savages outwitted another, having instincts of danger that civilized men would have allowed to pass unnoticed. The Sioux found only the embers of a deserted camp, and saw the tracks of their enemies diverge in so many directions that it was useless to pursue.

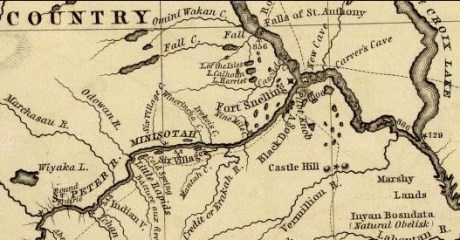

In 1839 the Chippewas on the upper Mississippi were required to come to Fort Snelling to receive their payments. That post was in Sioux territory, and the order gave offense to both nations. It required the presence of the United States troops to prevent murders even on the reservation. On the way home at Sunrise River, the Chippewas were surprised by a large force of Sioux, and one hundred and thirty-six were killed.

At the mouth of Crow Wing River, on the east bank of the Mississippi, is a ridge of gravel, on which there were shallow pits. The Indians said that, about fifteen years before, a war party of Sioux was above there on the river to attack the Sandy Lake band. A party of Chippewas concealed themselves in these pits, awaiting the descent of their enemies. The affair was so well managed that the surprise was complete. When the uncautious Sioux floated along within close range of their guns, the Chippewa warriors rose and delivered their fire into the canoes. Some got ashore and escaped through the woods to the westward, but a large portion were killed.

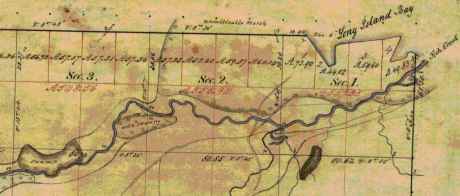

Detail of Crow Wing River from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843.

~ David Rumsey Map Collection

While crossing the Elk River, between the falls of St. Anthony and those of St. Cloud, a squaw ran into the water, screaming furiously, followed by a man with a club. This was her lord and master, bent on giving her a taste of discipline very common in Indian life. She succeeded in escaping this time by going into deep water. Her nose had been disfigured by cutting away most of the fleshy portions, as a punishment for unfaithfulness to a husband, who was probably worse than herself.

At the mouth of Crow Wing River was an Indian skipping about with the skin of a skunk tied to one of his ankles. There was also in a camp near the post another Chippewa, who had murdered a brother of the lively man. There is no criminal law among them but that of retaliation. Any member of the family may execute this law at such time and manner as he shall decide. This badge of skunk’s skin was a notice to the murderer that the avenger was about, and that his mission was not fulfilled. Once the guilty man had been shot through the thigh, as a foretaste of what was to follow. The avenger seemed to enjoy badgering his enemy, whom he informed that although he might be occasionally wounded, it was not the intention at present to kill him outright. If the victim should kill his persecutor, he well knew that some other relative would have executed full retaliation.

~ The Assassination of Hole In The Day [the Younger] by Anton Treuer, 2010.

Hole In The Day the Younger

aka Kue-wee-sas (Gwiiwizens [Boy or Lad])

(1825-1868)

Bagone-giizhig the Younger

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

This Chippewa brave, Bug-on-a-ke-dit, lived on a knoll overlooking the Mississippi River, four miles above Little Rock, where he had a garden. He appeared at the payment at La Pointe, in 1848, with a breech cloth and scanty leggings. This was partially for showing off a very perfect figure, tall, round and lithe, the Apollo of the woods. His scanty dress enabled him to exhibit his trophies in war. The dried ears of his foes, a part of whom were women, were suspended at his neck. Around his tawny arms were bright brass bands, but there was nothing of which he was more proud than a bullet hole just below the right breast. The place of the wound was painted black, and around it circles of red, yellow and purple; other marks on the chest, arms and face told of the numbers he had slain and scalped, in characters well understood by all Chippewas. The numbers of eagle feathers in his hair informed the savage crowd how many battles he had fought. He was not, like Grizzly Bear, a great orator, but resembled him in getting drunk at every opportunity. He managed to procure a barrel of whiskey, which he carried to his lodge. While it was being unloaded it fell upon and crushed him to death. Looking up a grass clad hill, a dingy flag was seen (1848) fluttering on a pole where he was buried. He often repeated with great zest the mode by which the owners of two of the desecrated ears were killed. His party of four braves discovered some Sioux lodges on the St. Peters, from which all the men were absent. The squaws lodged their hereditary enemies over night with their accustomed hospitality. Bug-on-a-ke-dit and his party concealed themselves during the day, and at dark each one attacked a lodge. Seven women and children were slaughtered. His son Kue-wee-sas, or Po-go-noy-ke-schik, was a much more respectable and influential chief.

An hundred years since, the Sioux had an extensive burial ground, on the outlet of Sandy Lake, a few miles east of the Mississippi River. Their dead were encased in bark coffins and placed on scaffolds supported by four cedar posts, five or six feet high. This was done to prevent wolves from destroying the bodies. Thirty years since some of these coffins were standing in a perfect condition, but most of them were broken or wholly fallen, only the posts standing well whitened by age. The Chippewas wrap the corpse in a blanket and a roll of birch bark, and dig a shallow grave in which the dead are laid. A warrior is entitled to have his bow and arrow, sometimes a gun and and a kettle, laid beside him with his trinkets. Over the mound a roof of cedar bark is firmly set up, and the whole fenced with logs or protected in some way against wolves and other wild animals. There is a hole at one or both ends of the bark shelter, in which is friends place various kinds of food. Their belief in a spirit world hereafter is universal. If it is a hunter or warrior, he will need his arms to kill game or to slay his enemies. Their theory is that the dog may go to the spiritual country, as a spirit, also his weapons, and the food which is provided for the journey. To him every thing has its spiritual as well as its material existence. Over all is the great spirit or kitchi-manitou, looking after the happiness of his children here and hereafter.

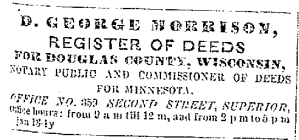

Stephen Bonga

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Winter travelling in those northern regions is by no means so uncomfortable as white men imagine. By means of snow shoes the Indian can move in a straight course towards his village, without regard to the trail. In the short days of winter he starts at day break and travels util dark. Stephen said he made fifty miles a day in that way, which is more than he could have done in summer.

At night they endeavor to find a thicket where there is a screen against the wind and plenty of wood. They scoop away the snow with their shoes and start a fire at the bottom of the pit. Around this they spread branches of pine, balsam or cedar, and over head make a shelter of brush to keep off the falling snow. Probably they have a team or more of dogs harnessed to sledges, who take their places around the fire. Here they cook and eat an enormous meal, when they wrap themselves in blankets for a profound sleep. Long before day another heavy meal is eaten. Everything is put in its proper package ready to start as soon as there is light enough to keep their course.

– Freelang Ojibwe-English by Weshki-ayaad, Charles Lippert and Guy T. Gambill

– Ojibwe People’s Dictionary by the Department of American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota

Many Indian words have originated since the white people came among them. A large proportion of their proper names are very apt expressions of something connected with the person, lake, river, or mountain to which they are applied. This people, in their primitive state, knew nothing of alcohol, coffee, tea, fire-arms, money, iron, and hundreds of other things to which they gave names, generally very appropriate ones. A negro is black meat; coffee is black medicine drink; tea, red medicine drink; iron, black metal; gold, yellow metal. I was taking the altitude of the sun at noon near Red Lake Mission with a crowd of Chippewas standing around greatly interested. They had not seen the liquid metal mercury, used for an artificial horizon in such observations, which excited their especial astonishment, and they had no name for it. One of them said something which caused a general expression of delight, for which I enquired the reason. He had coined a word for mercury on the spot, which means silver water.

Detail of Minnesota Point during George Stuntz’s survey contract during August-October of 1852.

~ Barber Papers (prologue): Stuntz Surveys Superior City 1852-1854

This family’s sugar bush was located at or near Silver Creek (T53N-R10W).

~ General Land Office Records

Indian trail to Rockland townsite overlooking English/Mineral Lake and Gogebic Iron Range.

~ Penokee Survey Incidents: Number V

Coasting along the beach northward from the mouth of the St. Louis River, on Minnesota Point, I saw a remarkable mark in the sand and went ashore to examine it. The heel and after part was clearly human. At the toes there was a cleft like the letter V and on each side some had one, others two human toes. Not far distant were Indians picking berries under the pine trees, which then covered the point in its entire length. We asked the berrypickers what made those tracks. They smiled and offered to sell us berries, of which they had several bushels, some in mokoks of birch bark, others in their greasy blankets. An old man had taken off his shirt, tied the neck and arms, and filled it half full of huckleberries. By purchasing some, (not from the shirt or blanket) we obtained an explanation of the nondescript tracks. There was a large family, all girls, whose feet were deformed in that manner. It was as though their feet had been split open when young halfway to the instep, and some of the toes lost. They had that spring met with a great loss by the remorseless bear. On the north shore, thirty miles east of Duluth, they had a fine sugar orchard, and had made an unusual quantity of sugar. A part was brought away, and a part was stored high up in trees in mokoks. There is nothing more tempting than sugar and whiskey to a bear. When this hard working family returned for their sugar and dried apples, moistened with whiskey, to lure bruin on to his ruin. A trap fixed with a heavy log is set up across a pen of logs, in the back end of which this bait is left, very firmly tied between two pieces of wood. This is fastened to a wooden deadfall, supporting one end of a long piece of round timber that has another piece under it. The bear smells the bait from afar, goes recklessly into the pen, and commences to gnaw the pieces of wood; before he gets much of the bait the upper log falls across his back, crushing him upon the lower one, where, if he is not killed, his hind legs are paralyzed. These deadly pens are found everywhere in the western forests. Two bears ranging along the south shore of English Lake, in Ashland County, Wisconsin, discovered some kegs of whiskey which contraband dealers had concealed there. With blows from their heavy paws they broke in the heads of the kegs and licked up the contents. They were soon in a very maudlin state, rolling about on the ground, embracing each other in an affectionate manner and vainly trying to go up the trees. Before the debauch was ended they were easily captured by a party of half-breeds. There are Indians who acknowledge the bear to be a relation, and profess a dislike to kill them. When they do they apologize, and say they do it because they are “buckoda,” or because it is necessary.

Detail of the Porcupine Mountains between the Montreal River and Ontonagon River from Map of the Mineral Lands Upon Lake Superior Ceded to the United States by the Treaty of 1842 With the Chippeway Indians.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

At Ontonagon, a very sorry looking young Indian came out of a lodge on the west side of the river and expressed a desire to take passage in our boat. There had been a great drunk in that lodge the day before. The squaws were making soup of the heads of white fish thrown away by the white fishermen. Some of the men were up, others oblivious to everything. Our passenger did not become thoroughly sober until towards evening. We passed the Lone Rock and encamped abreast of the Porcupine Mountains. Here he recovered his appetite. The next day, near the Montreal River, a squaw was seen launching her canoe and steering for us. She accosted the young fellow, demanding a keg of whiskey. He said nothing. She had given him furs enough to purchase a couple of gallons and he had made the purchase, but between himself and his friends it had completely disappeared. The old hag was also fond of whiskey. The fraud and disappointment put her into a rage that was absolutely fiendish. Her haggard face, long, coarse, greasy, black hair, voluble tongue and shrill voice perfected that character.

Turning into the mouth of the river we found a party from Lake Flambeau fishing in the pool at the foot of the Great Fall. Their success had not been good, and of course they were hungry. One of our men spilled some flour on the sand, of which he could save but little. The Flambeaus were delighted, and, gathering up sand and flour together, put the mixture in their kettle. The sand settled at the bottom, and the flour formed an excellent porridge for hungry aboriginees.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Mushinnewa and Waubannika, Chippewas, lived at Bad River, near Odana. Mushinnewa had a very bad reputation among his tribe. He was not only quarrelsome when drunk, but was not peaceable when sober. He broke Waubannika’s canoe into fragments, which was resented by the wife of the latter on the spot. She made use of the awl with which she was sewing the bark on another canoe, as a weapon, and stabbed old Mushinnewa in several places so severely that it was thought he would die. He threatened to kill her, and she fled with her husband to Lake Flambeau. But Mushinnewa did not die. He had a son as little liked by the Odana band as himself. In a drunken affray at Ontonagon another Indian killed him. The murderer then took the body in his canoe, brought it to Bad River and delivered it to old Mushinnewa. According to custom the Indian handed the enraged father the knife with which his son was killed, and baring his breast told him to strike. The villagers were happy to be rid of the young villain, and took the knife from the hand of his legal avenger. A barrel of flour covered the body, and before night Mushinnewa adopted the Indian as his son.

Two varieties of willow, the red and the yellow, grow on the low land, at the margin of swamps and streams, which have the name of kinnekinic. During the day’s journey, a few sticks are cut and carried to the camp. The outer bark is scraped away from the inner bark, which curls in a fringe around the stick, which is forced in the ground before a hot fire, and occasionally turned. In the morning it is easily crumpled in the hands, and put into the tobacco pouch. If they are rich enough to mix a little tobacco with the kinnekinic, it is a much greater luxury. As they spend a large part of their leisure time in smoking, they are compelled to be content with common willow bark, which is a very weak narcotic. Tobacco is not grown as far north as the country of the Chippewas, but it is probable they had it through traffic with the tribes of Virginia, North Carolina and the Gulf States, in times very remote. Pipes are found in the works of the mounds builders that are very ancient, showing that they had something to smoke, which must have been a vegetable.

Detail of where the “Lake Long” [Lake Owen] and St. Croix foot paths start along Fish Creek.

~ Barber Papers: “Barbers Camp” Fall of 1855

~ History of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, by Western Historical Co., 1883, page 276

Staggering around in a drunken crowd at La Pointe was a handsome Chippewa buck, as happy as whiskey can make any one. The tomahawk pipe is not an instrument of war, though it has that form. Its external aspect is that of a real tomahawk, intended to let out the brains of the foe. It is made of cast iron, with a round hollow poll, about the size of a pipe. The helm or handle is the stem, frequently decorated in the height of savage art, with ribbons, porcupine quills, paint and feathers. One thoroughly adorned in this manner has aperatures through the handle cross wise, so large and numerous that it is a mechanical wonder how the smoke can be drawn through it to the mouthpiece. No Indian is without a pipe of some kind, very likely one that is an heirloom from his ancestors. It is only in a passion that his knife or tomahawk pipe becomes dangerous. This genial buck had been struck with the poll of such a pipe when all hands were fighting drunk. It had cut a clear round hole in his head, hear the top, sinking a piece of skull with the skin and hair well into his brains. A surgeon with his instrument could not have made a more perfect incision. Inflammation had not set in and he was too busy with his boon companions to think of the wound. It was about twenty-four hours after it occurred when he stepped into his canoe and departed. When Mr. Beasley went up the Fish River, a few days afterwards a funeral was going on at the intersection of the Lake Long and the St. Croix trails, and the corpse had a cut in the head made by the pole of a tomahawk. From this event, no doubt, a family quarrel commenced that may continue till the race is extinct. The injured spirit of the fallen Indian demands revenge. In the exercise of retaliation it may be carried by his relations a little beyond retaliating justice, which will call on the other side for a victim, and so on to other generations.

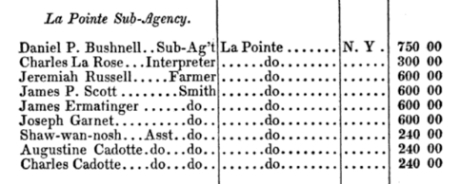

In a lodge between the agency and the mission there was a young girl very sick. Probably it is my duty to say that she was not only young but beautiful, but at this time she was only wretched. Whether in her best health and estate the term beauty could be applied I very much doubt, as such cases are extremely rare among Indians, compared by our standard. A “grand medicine” had been got up expressly for the purpose of curing her. The medicine lodge was about thirty feet in length, made of green boughs. The feast, without which no evil spirit would budge one inch, had been swallowed, and the dance was at its height, in which some women were mingled with the men. Their shrieks, yelling and gesticulations should have frightened away all the matchi-manitous at La Pointe. The mother of the girl seemed to be full of joy, the bad spirit which afflicted her child was so near being expelled. As they made the circuit of the dance they thrust a large knife into the air towards the northwest, by which they gave the departing demon a stab as he made his escape from the lodge. This powow raged around the poor girl all the afternoon and till midnight, when the medicine man pronounced her safe. Before sundown the next day we saw them law her in a shallow grave, covered with cedar bark.

Father Nicolas Perrot

~ Wikipedia.org

Father Perret, who was among the Natches as far back as 1730, gives a portrait of a medicine man of that tribe at that time. It answers so well for those I have seen among the Chippewas that I give his description at length. For the Chippewa juggler I must except, however, the practice of abstinence and also the danger of losing his head. A feast is the first thing and the most essential.

“This nation, like all others, has its medicine man. They are generally old men, who, without study or science, undertake to cure all complaints. All their art consists in different jugglings, that is to say, they sing and dance night and day about the sick man, and smoke without ceasing, swallowing the smoke of the tobacco. These jugglers eat scarcely anything while engaged with the sick, but their chants and dances are accompanied by contortions so violent that, although they are entirely naked and should suffer from cold, they are always foaming at the mouth. They have a little basket in which they keep what they call their spirits, that is to say, roots of different kinds, heads of owls, parcels of the hair of deer, teeth of animals, pebbles and other trifles. To restore health to the sick they invoke without ceasing something they have in their basket. Sometimes they cut with a flint the part afflicted, suck out the blood, and in returning it immediately to the disk they spit out a piece of wood, straw or leather, which they have concealed under their tongue. Drawing the attention of the sick man, ‘there,’ they say, ‘is the cause of his sickness.’ These medicine men are always paid in advance. If the sick man recovers their gain is considerable, but if he dies they are sure to have their heads cut off by his relations.”

“Osawgee Beach. Superior, Wis.” postcard, circa 1920:

“Ojibwe chief Joseph Osawgee was born in Michigan in 1802 and came to Wisconsin Point as a young boy. There he established Superior’s first shipyard—a canoe-making outfit along the Nemadji River near Wisconsin Point. His birch bark canoes supplied transportation for both Ojibwe trappers and French Voyageurs. Chief Osawgee signed the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe on behalf of the Fond du Lac Ojibwe—and subsequently lost his land. He died in Solon Springs, Wisconsin, in 1876.”

~ Zenith City Online

Joseph Ozaagii

~ Geni.com

~ Indian Country Today Media Network

“Chief O-sau-gie Built First ‘Ships’ in City of Superior (He Was Head of Small Chippewa Band when Superior was Tiny Spot)”

As a rare example of the industry and probity among northern Indians, I take pleasure in recording the name of Osagi. His hunting ground and sugar camp lay to the west of La Pointe, on Cranberry River, where he had a cabin. In traversing that region I had as a guide a rude map and sketch of the streams made by him on a sheet of post office paper with a red pencil. Osagi was never idle and never drunk. Dr. Livermore was at this time the agent for the tribes at the west end of Lake Superior, and related the following instance of attention and generosity which is worthy of being reported. Osagi frequently made the agency presents, and Dr. Livermore, of course, did the same to his Otchipwee friends. Late in the fall, as the fishing season was about to close, he sent a barrel of delicious trout and white fish to the agency, which, by being hung up separately, would in this cool climate remain good all winter. The interpreter left a message from the donor with the fish, that he did not want any present in return, because in such a case there would be on his part no gifts, and he wished to make a gift. Dr. Livermore assented, but replied that if Osagi should ever be in need the agent expected to be informed of it. During the next winter a message came to Dr. Livermore stating that his friend wanted nothing, but that a young man, his cousin, was just in from Vermillion Lake, where he lived. The young man’s father and family could no longer take fish at Vermillion, and had started for Fonddulac. The old man was soon attacked by rheumatism, and for many days the whole party had been without provisions. Would the agent make his uncle a present of some flour? Of course this was done, and the young messenger started with a horse load of eatables for the solitary lodge of his father, on the St. Louis River, two hundred miles distant. This exemplary Indian, by saving his annuities, and by his economy, had accumulated money enough to buy a piece of land, and placed it in the hands of the agent. when the surveyors had subdivided the township opposite La Pointe, on the mainland, he bought a fraction and removed his family to it as a permanent home. In a few months the small pox swept off every member of that family but the mother.

[CHARLES WHITTLESEY.]

To be continued in Among The Otchipwees: III…

Among The Otchipwees: I

May 28, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Magazine of Western History Illustrated

No. 2 December 1884

as republished in

Magazine of Western History: Volume I, pages 86-91.

AMONG THE OTCHIPWEES.

Like all the northern tribes, the Chippewas are known by a variety of names. The early French called them Sauteus, meaning people of the Sault. Later missionaries and historians speak of them as Ojibways, or Odjibwes. By a corruption of this comes the Chippewa of the English.

“No-tin” copied from 1824 Charles Bird King original by Henry Inman in 1832-33. Noodin (Wind) was a prominent Chippewa chief from the St. Croix country.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

On the south of the Chippewas, in 1832, across the Straits of Mackinaw, were the Ottawas. Some of this nation were found by Champlain on the Ottawa River of Canada, whom he called Ottawawas. In later years there were some of them on Lake Superior, of whom it is probable the Lake Court Oreille band, in northwestern Wisconsin, is a remainder. The French call them “Court Oreillés,”, or short ears. All combined, it is not a powerful nation. Many of them pluck the hair from a large part of the scalp, leaving only a scalp lock. This custom they explain as a concession to their enemies, in order to make a more neat and rapid job of the scalping process. A thick head of coarse hair, they say, is a great impediment. Probably the true reason is a notion of theirs that a scalp lock is ornamental. The practice is not universal among Ottawas, and is not common with the neighboring tribes. These were the people who committed the massacre of the English garrison at Old Mackinaw, in 1763.

![Mah-kée-mee-teuv, Grizzly Bear, Chief of the [Menominee] Tribe by George Catlin, 1831. ~ Smithsonian Institute](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/1831-mah-kee-mee-teuv-grizzly-bear-by-george-catlin.jpg?w=230&h=300)

“Mah-kée-mee-teuv, Grizzly Bear, Chief of the [Menominee] Tribe” by George Catlin, 1831.

~ Smithsonian Institute

The Oneidas, a small remnant of that nation, from New York, were located on Duck River, near Fort Howard, and the Tuscaroras on the south shore of Lake Winnebago.

Detail from “Among The Winnebago [Ho-Chunk] Indians. Wah-con-ja-z-gah (Yellow Thunder) Warrior chief 120 y’s old” stereograph by Henry Hamilton Bennett, circa 1870s.

~ J. Paul Getty Museum

Plaster life cast of Sac leader Black Hawk (Makatai Meshe Kiakiak) reproduced by Bill Whittaker (original was made circa 1830) on display at Black Hawk State Historic Site.

~ Wikipedia.org

Next to the Menominees on the west were the Winnebagoes, a barbarous, warlike and treacherous people, even for Indians. Their northern border joined the Chippewas. Yellow Thunder’s village, in 1832, was on the trail from Lake Winnebago to Fort Winnebago, south of the Fox River about half way. He was more of a prophet, medicine man or priest, than warrior. In the Black Hawk war man of the Winnebago bucks joined the Sacs and the Foxes. Only four years before the United States was obliged to send an expedition against them, and to build a stockade at the portage. Their chiefs, old men, and medicine men, professed to be very friendly to us, but kept up constant communications with Black Hawk. When he was beaten at the Bad Ax River, and his warriors dispersed, they followed the old chief into the northern forest, captured him, and delivered him to the United States forces.

One of the causes of the Black Hawk War in 1832 was the murder of a party of Menominees near Fort Crawford, by the Sacs and Foxes. There was an ancient feud between those tribes which implies a series of scalping parties from generation to generation.

Sac leader “Ke-o-kuk or the Watchful Fox” by Thomas M. Easterly, 1847.

~ Missouri History Museum

As the Menominees were at peace with the United States, and their camps were near the garrison, they were considered to have been under Federal protection, and their murder as an insult to its authority. The return of Keokuk’s band to the Rock River country brought on a crisis in the month of May. The Menominees were anxious to avenge themselves, but were quieted by the promise of the government that the Sacs and Foxes should be punished. They offered to accompany our troops as scouts or spies, which was not accepted until the month of July, when Black Hawk had returned to the Four Lakes, where is now the city of Madison.

On a bright afternoon, about the middle of the month, a company of Menominee warriors emerged in single file from the woods in rear of Fort Howard at the head of Green Bay. They numbered about seventy-five, each one with a gun in his right hand, a blanket over his right shoulder, held across the breast by the naked left arm, and a tomahawk. Around the waist was a belt, on which was a pouch and a sheath, with a scalping knife. Their step was high and elastic, according to the custom of the men of the woods. On their faces was an excess of black paint, made more hideous by streaks of red. Their coarse black hair was decorated with all the ribbons and feathers at their command. Some wore moccasins and leggings of deer skin, but a majority were barefooted and barelegged. They passed across the common to the ferry, where they were crossed to Navarino, and marched to the Indian Agency at Shantytown. Here they made booths of the branches of trees. Captain or Colonel Hamilton, a son of Alexander Hamilton, was their commander. As they had an abundance to eat and were filled with martial prowess, they were exceedingly jubilant.

“A view of the Butte des Morts treaty ground with the arrival of the commissioners Gov. Lewis Cass and Col. McKenney in 1827” by James Otto Lewis, 1835.

~ Library of Congress

Their march was up the valley of the river, recrossing above Des Peres, passing the great Kakolin, and the Big Butte des Morts to the present site of Oshkosh. Thence crossing again they followed the trail to the Winnebago villages, past the Apukwa or Rice lakes to Fort Winnebago, making about twenty miles a day. On the route they were inclined to straggle, presenting nothing of military aspect except a uniform of dirty blankets. Colonel Hamilton was not able to make them stand guard, or to send out regular pickets. They were expert scouts in the day time, but at night lay down to sleep in security, trusting to their dogs, their keen sense of hearing and the great spirit. On the approach of day they were on the alert. It is a rule in Indian tactics to operate by surprises, and to attack at the first show of light in the morning.

From Fort Winnebago they moved to the Four Lakes, where Madison now is. Black Hawk had retired across the Wisconsin River, where there was a skirmish on the 21st of July, and the battle of the Bad Ax was being fought.

Photograph of Pierre Jean Édouard Desor (Swiss geologist and professor at Neuchâtel academy) from Wisconsin Historical Society. Desor and others were employed to survey for Report on the geology and topography of a portion of the Lake Superior Land District in the state of Michigan: Part I, Copper Lands; Part II, The Iron Region.

A few miles southwesterly of Waukedah, on the branch railroad to the iron mines of the upper Menominee, is a lake called by the Indians “Shope,” or Shoulder Lake, which I visited in the fall of 1850, in company with the late Edward Desor, a scientist of reputation in Switzerland. It discharges into the Sturgeon River, one of the eastern branches of the Menominee. There was a collection of half a dozen lodges, or wigwams, covered with bark, with a small field of corn, and the usual filth of an Indian village. The patriarch, or “chief” of that clan, came out to meet us, attended by about thirty men, women and children. By the traders he was called “Governor.” His nose was prominently Roman. He stood evenly on both feet, with his limbs bare below the knees. The right arm was also bare, and over the left shoulder was thrown a dirty blanket, covering the chest and the hips. A mass of coarse black hair covered the head, but was pushed away from the face. The usual dark, steady, snakelike, black eye of the race examined us with a piercing gaze. His face, with its large, well proportioned features, was almost grand. his pose was easy, unstudied and dignified, like one’s ideal of the Roman patrician of the time of Cicero, such as sculptors would select as a model.

This band were the Chippewas, but the coast of Green Bay was occupied by Menominees or Menomins, known to the French as “Folle Avoines,” or “Wild Rice” Indians, for which Menomin is the native name. Above the Twin Falls of the Menominee was an ancient village of Chippewas, called the “Bad Water” band, which is their name for a series of charming lakes not far distant, on the west of the river. They said their squaws, a long time since, were on the lakes in a bark canoe. Those on the land saw the canoe stand up on end, and disappear beneath the surface with all who were in it. “Very bad water.” From that time they were called the “Bad Water” lakes.

The Bad Water Band of Lake Superior Chippewa was first documented by Captain Thomas Jefferson Cram in his 1840 report to Congress.

~ Dickinson County Library

Cavalier was a half-breed French and Menominee. He was a handsome young man, and was well aware of it. Though he was married, the squaws received his attentions without much reserve. Half-breeds dress like the whites of the trading post, and not as Indians. Their hair is cut, and instead of a blanket they have coarse overcoats, and wear hats. Many of them are traders, a class mid-way between the whites and Indians.

No Princess Zone: Hanging Cloud, the Ogichidaakwe is a popular feature here on Chequamegon History.

Polygamy is the most fixed of savage institutions, and one that the half-breed and trader does not despise. Chippewa maidens, and even wives, have many reasons for looking kindly upon men who wear citizens’ clothes and trade in finery. Moccasins they can make very beautifully, but shawls and strouds of broadcloth, silk ribbons, pewter broaches, brass rings, and glass beads they cannot. These are the work of the white man. But none of that race, man or maid, has a more powerful passion for the ornamental than the children of the forest, male or female. Let us not judge the latter too harshly – poor, ignorant, suffering slave, with none of the protection which the African slave could sometimes invoke against barbarian cruelty. Their children are as happy and playful as those of the white race. Before they become men and women they are frequently beautiful, the deep brunette of their complexion having, on the cheek, a faint tinge of a lighter color, especially among those from the far north, like the “Bois Forts” of Rainy Lake. Young lads and girls have well formed limbs and straight figures, with agile and graceful movements. At this age the burdens and hardships of the squaws have not deformed them. The smoke of the lodge has not tanned their skin to Arab-like blackness nor inflamed their eyes. In about ten years of drudgery, rowing the canoe, putting up lodges, bearing children, and not infrequent beatings by her lord, the squaw is an old woman. Her features become rough and angular, the melodious voice of childhood is changed to one that is sharp, shrill, piercing and disagreeable. At forty she is a decrepit old woman, and before that time, if her master has not put her away, he may have installed number two as an additional tyrant.

A Menominee village in “Village of Folle-Avoines” by Francis de Laporte de Castelnau, 1842.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Well up the Peshtigo, on a rainy, foggy afternoon, we made an early camp near a dismal swamp on the low ground. On the other side of the river, at a considerable distance, was heard the moans of a person evidently in great distress. Cavalier was sent over to investigate. He found a wigwam with a Menominee and two women, both wives. The youngest was on a bridal tour. The old wife had broken her thigh about a month before, which had not been set. She was suffering intensely, the limb very much swollen, and the bridal party wholly neglecting her. It was evident that death was her only relief. A strong dose of morphine gradually moderated her groans, which were more pathetic than anything that ever reached my ears. Before morning she was quiet.

As the water was very low I went through the gorge of the Menominee above the Great Bekuennesec, or Smoky Falls. Near the lower end, and in hearing of the cataract, I saw through the rocky chasm a mountain in the distance to the northeast. My half-breed said the Indians called it Thunder Mountain. They say that thunder is caused by an immense bird which goes there, when it is enveloped by clouds and flaps its wings furiously.

Turning away from the mists of the cataract and its never ceasing roar, we went southwesterly among the pines, over rocks and through swamps, to a time worm trail leading from the Bad Water village to the Pemenee Falls. This had been for many years the land route from Kewenaw Bay to the waters of Green Bay at the mouth of the Menominee River. When the copper mines on Point Kewenaw were opened, in 1844 and 1845, the winter mail was carried over this route on dog trains, or on the backs of men. Deer were very plenty in the Menominee valley. Bands of Pottawatomies scoured the woods, killing them by hundreds for their skins. We did not kill them until near the close of the day, when about to encamp. Cavalier went forward along the trail to make camp and shoot a deer. I heard the report of his gun, and expected the usual feast of fresh venison. “Where is your deer?” “Don’t know; some one has put a spell on my gun, and I believe I know who did it.”

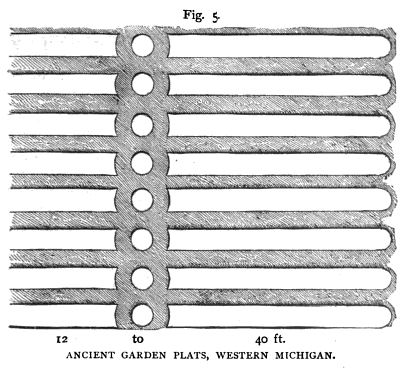

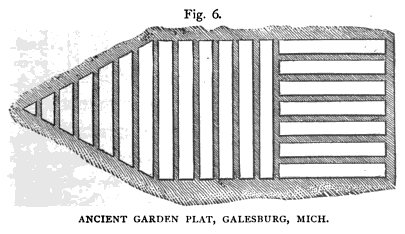

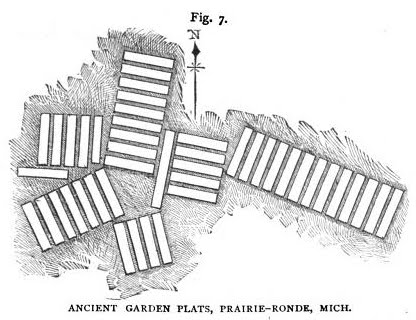

Map of Lac Vieux Desert with “Catakitekon” [Gete-gitigaan (old gardens)] from Thomas Jefferson Cram’s 1840 fieldbook.

~ School District of Marshfield: Digital Time Travelers

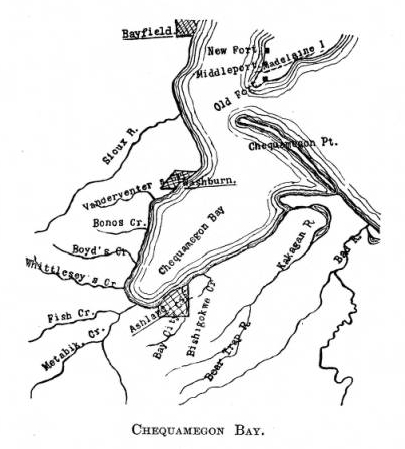

The Chippewas are spread over the shores and the rivers of Lake Superior, Lake Nipigon, the heads of the Mississippi, the waters of Red Lake, Rainy Lake and the tributaries of the Lake of the Woods. When Du Lhut and Hennepin first became acquainted with the tribes in that region, the Sioux, Dacotas, or Nadowessioux, and the Chippewas were at war, as they have been ever since. The Sioux of the woods were located on the Rum, or Spirit River, and their warriors had defeated the Chippewas at the west end of Lake Superior. Hennepin was a prisoner with a band of Sioux on Mille Lac, in 1680, at the head of Rum River, called Isatis. When Johnathan Carver was on the upper Mississippi, in 1769, the Chippewas had nearly cleared the country between there and Lake Superior of their enemies. In 1848 their war parties were still making raids on the Sioux and the Sioux upon them.

CHARLES WHITTLESEY.

To be continued in Among The Otchipwees: II…

Colonel Charles Whittlesey

May 27, 2016

By Amorin Mello

C.C. Baldwin was a friend, colleague, and biographer of Charles Whittlesey.

~ Memorial of Charles Candee Baldwin, LL. D.: Late President of the Western Reserve Historical Society, 1896, page iii.

This is a reproduction of Colonel Charles Whittlesey’s biography from the Magazine of Western History, Volume V, pages 534-548, as published by his successor Charles Candee Baldwin from the Western Reserve Historical Society. This biography provides extensive and intimate details about the life and profession of Whittlesey not available in other accounts about this legendary man.

Whittlesey came to Lake Superior in 1845 while working for the Algonquin Mining Company along the Keweenaw Peninsula’s copper region. His first trip to Chequamegon Bay appears to have been in 1849 while doing do a geological survey of the Penokee Mountains for David Dale Owen. Whittlesey played a dramatic role in American settlement of the Chequamegon Bay region. Whittlesey convinced his brother, Asaph Whittlesey Jr., to move from the Western Reserve in 1854 establish what became the City of Ashland at the head of Chequamegon Bay as a future port town for extracting and shipping minerals from the Penokee Mountains. Whittlesey’s influence can still be witnessed to this day through local landmarks named in his honor:

Whittlesey published more than two hundred books, pamphlets, and articles. For additional research resources, the extensive Charles Whittlesey Papers are available through the Western Reserve Historical Society in two series:

Magazine of Western History, Volume V, pages 534-548.

COLONEL CHARLES WHITTLESEY.

Map of the Connecticut Western Reserve in Ohio by William Sumner, September 1826.

~ Cleveland Public Library

![Asaph Whittlesey [Sr], Late of Tallmadge, Summit Co., Ohio by Vesta Hart Whittlesey and Susan Everett Whittlesey, né Fitch, 1872.](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/asaph-whittlesey-vesta-hart.jpg?w=186&h=300)

[Father] Asaph Whittlesey [Sr], Late of Tallmadge, Summit Co., Ohio by [mother] Vesta Hart Whittlesey [posthumously] and [stepmother] Susan Everett Whittlesey, né Fitch, 1872.

~ Archive.org

War was then in the west, and his neighbors feared they might be the victims of the scalping knife. But the danger was different. In passing the Narrows, between Pittsburgh and Beaver, the wagon ran off a bank and turned completely over on the wife and children. They were rescued and revived, but the accident permanently impaired the health of Mr. Whittlesey.

Mr. Whittlesey was in Tallmadge, justice of the peace from soon after his arrival till near the close of his life, and postmaster from 1814, when the office was first established, to his death. He was again severely injured, but a strong constitution and unflinching will enabled him to accomplish much. He had a store, buying goods in Pittsburgh and bringing them in wagons to Tallmadge; and an ashery; and in 1818 he commenced the manufacture of iron on the Little Cuyahoga, below Middlebury.

The times were hard, tariff reduced, and in 1828 he returned to his farm prematurely old. He died in 1842. Says General Bierce,

“His intellect was naturally of a high order, his religious convictions were strong and never yielded to policy or expediency. He was plain in speech, sometimes abrupt. Those who respected him were more numerous than those who loved him. But for his friends, no one had a stronger attachment. His dislikes were not very well concealed or easily removed. In short, he was a man of strong mind, strong feelings, strong prejudices, strong affections and strong attachments, yet the whole was tempered with a strong sense of justice and strong religious feelings.”

[Uncle] Elisha Whittlesey

~ Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

Portrait of Reverend David Bacon from ConnecticutHistory.org:

“David Bacon (1771 – August 27, 1817) was an American missionary in Michigan Territory. He was born in Woodstock, Connecticut. He worked primarily with the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes, although they were not particularly receptive to his Christian teachings. He founded the town of Tallmadge, Ohio, which later became the center of the Congregationalist faith in Ohio.”

~ Wikipedia.org

Tallmadge was settled in 1808 as a religious colony of New England Congregationalists, by a colony led by Rev. David Bacon, a missionary to the Indians. This affected the society in which the boy lived, and exercised much influence on the morality of the town and the future of its children, one of whom was the Rev. Leonard Bacon. Rev. Timlow’s History of Southington says, “Mr. Whittlesey moved to Tallmadge, having become interested in settling a portion of Portage county with Christian families.” And that he was a man “of surpassing excellence of character.”

If it should seem that I have dwelt upon the parents of Colonel Whittlesey, it is because his own character and career were strongly affected by their characters and history. Charles, the son, combined the traits of the two. He commenced school at four years old in Southington; the next year he attended the log school house at Tallmadge until 1819, when the frame academy was finished and he attended it in winter, working on the farm in summer until he was nineteen.

The boy, too, saw early life on foot, horseback and with ox-teams. He found the Indians still on the Reserve, and in person witnessed the change from savage life and new settlements, to a state of three millions of people, and a large city around him. One of Colonel Whittlesey’s happiest speeches is a sketch of log cabin times in Tallmadge, delivered at the semi-centennial there in 1857.

~ Annual Report on the Geological Survey of the State of Ohio: 1837 by Ohio Geologist William Williams Mather, 1838, page 22.

In 1827 the youngster became a cadet at West Point. Here he displayed industry, and in some unusual incidents there, coolness and courage. He graduated in 1831, and became brevet second lieutenant in the Fifth United States infantry, and in November started to join his regiment at Mackinaw. He did duty through the winter with the garrison at Fort Gratiot. In the spring he was assigned at Green Bay to the company of Captain Martin Scott, so famous as a shot. At the close of the Black Hawk War he resigned from the army. Though recognizing the claim of the country to the services of the graduates of West Point, he tendered his services to the government during the Seminole Mexican war. By a varied experience his life thereafter was given to wide and general uses. He at first opened a law office in Cleveland, Ohio, and was fully occupied in his profession, and as part owner and co-editor of the Whig and Herald until the year 1837. He was that year appointed assistant geologist of the state of Ohio. Through very uneconomical economy, the survey was discontinued at the end of two years, when the work was partly done and no final reports had been made. Of course most of the work and its results were lost. Great and permanent good indeed resulted to the material wealth of the state, in disclosing the rich coal and iron deposit of southeastern Ohio, thus laying the foundation for the vast manufacturing industries which have made that portion of the state populous and prosperous. The other gentlemen associated with him were Professor William Mather as principal; Dr. Kirtland was entrusted with natural history. Others were Dr. S. P. Hildreth, Dr. Caleb Briggs, Jr., Professor John Locke and Dr. J. W. Foster. It was an able corps, and the final results would have been very valuable and accurate. In 1884, Colonel Whittlesey was sole survivor and said in this Magazine:

“Fifty years since, geology had barely obtained a standing among the sciences even in Europe. In Ohio it was scarcely recognized. The state at that time was more of a wilderness than a cultivated country, and the survey was in progress little more than two years. It was unexpectedly brought to a close without a final report. No provision was made for the preservation of papers, field notes and maps.”

Report of Progress in 1869, by J. S. Newberry, Chief Geologist, by the Geological Survey of Ohio, 1870.

Professor Newbury, in a brief resume of the work of the first survey (report of 1869), says the benefits derived “conclusively demonstrate that the geological survey was a producer and not a consumer, that it added far more than it took from the public treasury and deserved special encouragement and support as a wealth producing agency in our darkest financial hour.” The publication of the first board, “did much,” says Professor Newberry, “to arrest useless expenditure of money in the search for coal outside of the coal fields and in other mining enterprises equally fallacious, by which, through ignorance of the teachings of geology, parties were constantly led to squander their means.” “It is scarcely less important to let our people know what we have not, than what we have, among our mineral resources.”

“Descriptions of Ancient Works in Ohio. By Charles Whittlesey, of the late Geological Corps of Ohio.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume III., Article 7, 1852.

The topographical and mathematical parts of the survey were committed to Colonel Whittlesey. He made partial reports, to be found in the ‘State Documents’ of 1838 and 1839, but his knowledge acquired in the survey was of vastly greater service in many subsequent writings, and, as a foundation for learning, made useful in many business enterprises of Ohio. He had, during this survey, examined and surveyed many ancient works in the state, and, at its close, Mr. Joseph Sullivant, a wealthy gentleman interested in archaeology, residing in Columbus, proposed that, he bearing the actual expense, Whittlesey should continue the survey of the works of the Mound Builders, with a view to joint publication. During the years 1839 and 1840, and under the arrangement, he made examination of nearly all the remaining works then discovered, but nothing was done toward their publication. Many of his plans and notes were used by Messrs. Squier & Davis, in 1845 and 1846, in their great work, which was the first volume of the Smithsonian Contributions, and in that work these gentlemen said:

“Among the most zealous investigators in the field of American antiquarian research is Charles Whittlesey, esq., of Cleveland, formerly topographical engineer of Ohio. His surveys and observations, carried on for many years and over a wide field, have been both numerous and accurate, and are among the most valuable in all respects of any hitherto made. Although Mr. Whittlesey, in conjunction with Joseph Sullivant, esq., of Columbus, originally contemplated a joint work, in which the results of his investigations should be embodied, he has, nevertheless, with a liberality which will be not less appreciated by the public than by the authors, contributed to this memoir about twenty plans of ancient works, which, with the accompanying explanations and general observations, will be found embodied in the following pages.

“It is to be hoped the public may be put in possession of the entire results of Mr. Whittlesey’s labor, which could not fail of adding greatly to our stock of knowledge on this interesting subject.”

“Marietta Works, Ohio. Charles Whittlesey, Surveyor 1837.”

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume I., Plate XXVI.

It will be seen that Mr. Whittlesey was now fairly started, interested and intelligent, in the several fields which he was to make his own. And his very numerous writings may be fairly divided into geology, archaeology, history, religion, with an occasional study of topographical geology. A part of Colonel Whittlesey’s surveys were published in 1850, as one of the Smithsonian contributions; portions of the plans and minutes were unfortunately lost. Fortunately the finest and largest works surveyed by him were published. Among those in the work of Squier & Davis, were the wonderful extensive works at Newark, and those at Marietta. No one again could see those works extending over areas of twelve and fifteen miles, as he did. Farmers cannot raise crops without plows, and the geography of the works at Newark must still be learned from the work of Colonel Whittlesey.

~ Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Volume XIII., Article IV., page 2 of “Ancient Mining on the Shores of Lake Superior” by Charles Whittlesey.

He made an agricultural survey of Hamilton county in 1844. That year the copper mines of Michigan began to excite enthusiasm. The next year a company was organized in Detroit, of which Colonel Whittlesey was the geologist. In August they launched their boat above the rapids of the Sault St. Marie and coasted along the shore to where is now Marquette. Iron ore was beneath notice, and in truth was no then transportable, and they pulled away for Copper Harbor, and then to the region between Portage lake and Ontonagon, where the Algonquin and Douglas Houghton mines were opened. The party narrowly escaped drowning the night they landed. Dr. Houghton was drowned the same night not far from them. A very interesting and life-like account of their adventures was published by Colonel Whittlesey in the National Magazine of New York City, entitled “Two Months in the Copper Regions.” From 1847 to 1851 inclusive, he was employed by the United States in the survey of the country around Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi, in reference to mines and minerals. After that he spent much time in exploring and surveying the mineral district of the Lake Superior basin. The wild life of the woods with a guide and voyageurs threading the streams had great attractions for him and he spent in all fifteen seasons upon Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi, becoming thoroughly familiar with the topography and geological character of that part of the country.

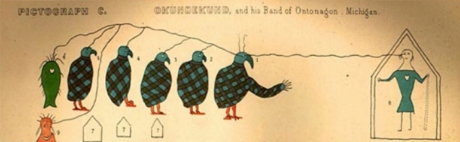

“Pictograph C. Okundekund [Okandikan] and his Band of Ontonagon – Michigan,” as reproduced from birch bark by Seth Eastman, and published as Plate 62 in Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, Volume I., by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, 1851. This was one of several pictograph petitions from the 1849 Martell delegation:

“By this scroll, the chief Kun-de-kund of the Eagle totem of the river Ontonagon, of Lake Superior, and certain individuals of his band, are represented as uniting in the object of their visit of Oshcabewis. He is depicted by the figure of an eagle, Number 1. The two small lines ascending from the head of the bird denote authority or power generally. The human arm extended from the breast of the bird, with the open hand, are symbolic of friendship. By the light lines connecting the eye of each person with the chief, and that of the chief with the President, (Number 8,) unity of views or purpose, the same as in pictography Number 1, is symbolized. Number 2, 3, 4, and 5, are warriors of his own totem and kindred. Their names, in their order, are On-gwai-sug, Was-sa-ge-zhig, or The Sky that lightens, Kwe-we-ziash-ish, or the Bad-boy, and Gitch-ee-man-tau-gum-ee, or the great sounding water. Number 6. Na-boab-ains, or Little Soup, is a warrior of his band of the Catfish totem. Figure Number 7, repeated, represents dwelling-houses, and this device is employed to deonte that the persons, beneath whose symbolic totem it is respectively drawn, are inclined to live in houses and become civilized, in other words, to abandon the chase. Number 8 depicts the President of the United States standing in his official residence at Washington. The open hand extended is employed as a symbol of friendship, corresponding exactly, in this respect, with the same feature in Number 1. The chief whose name is withheld at the left hand of the inferior figures of the scroll, is represented by the rays on his head, (Figure 9,) as, apparently, possessing a higher power than Number 1, but is still concurring, by the eye-line, with Kundekund in the purport of pictograph Number 1.”

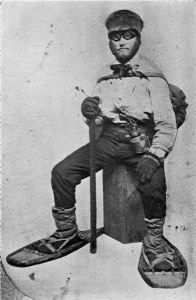

“Studio portrait of geologist Charles Whittlesey dressed for a field trip.” Circa 1858.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society