Kohl, J. G. “Remarks on the Conversion of the Canadian Indians and some Stories of Conversion” Part 2 of 2

June 21, 2018

By Leo

Part 1|Part 2

This is part two of, Bemerkungen über die Bekehrung canadischer zum Christenthum und einige Bekehrungsgeschichten (1859) (Remarks on the Conversion of the Canadian Indians and some Stories of Conversion), by Johann Georg Kohl published in the Augsburg-based, German-language magazine, Das Ausland. For information on the translation process and significance of this article, see part one. For Chequamegon History’s concluding analysis, scroll to the bottom of this post.

Das Ausland: Eine Wochenschrift Fur Kunde des geistigen und sittlichen Lebens der Völker

[The Foreign Lands: A weekly for scholars of the moral and intellectual lives of foreign nations]

Nr. 3 15 January 1859

Remarks on the conversion of Canadian Indians to Christianity and some conversion stories

By J.G. Kohl

(conclusion)

Since pagan marriage ties are usually very loose, and can be dissolved under Indian laws and customs at the slightest opportunity, a baptism of a married man is at the same time a re-marriage and a firm Christian marriage. It is all the more necessary to state something about this, since the Indian nations all permit polygamy. Of course, most men have only one wife because they find it difficult to feed several. If this isn’t the case with a baptized man, he must renounce the majority of his wives. The missionaries leave him the choice. He can keep the one whom he most loves. Usually, these ungrateful husbands then have the cruelty to leave the loyal old ones. Women who have been with them the longest are told goodbye, and the man settles down with the last and youngest in the bosom of the church.

Even in the language of the Indians, some reforms must be made upon baptism. These are often the hardest changes to perform. The pagan language of the Indians has many peculiarities which cannot be used after baptism, and permitting their use in Christianity would violate the dignity of religion.

From Dr. Rand Valentine via email: “Many languages in the world have a special grammatical system called Evidentiality, by which one is essentially required to indicate the source of information that one is reporting. Lots of languages make grammatical distinctions between first hand (visually observed, and in some languages, auditorily heard), hearsay (you heard it from someone else, who might have been a first-hand observer), inference (Joe must be sick, he was not feeling well and didn’t come into work today), common knowledge (everyone knows that frogs can’t fly), etc. The Ojibwe definitely have an evidential system grammatically, so when they talked in the 19th century about things from the Bible, they would say, “the alleged Jesus,” meaning, “I didn’t personally see this, and no one I know did,” etc. This hugely annoyed Baraga, who wanted them to treat the Bible as truth.” (Image: Baraga, F. A Theoretical and Practical Grammar of the Otchipwe Language. (1850). pg. 95.

From Dr. Rand Valentine via email: “Many languages in the world have a special grammatical system called Evidentiality, by which one is essentially required to indicate the source of information that one is reporting. Lots of languages make grammatical distinctions between first hand (visually observed, and in some languages, auditorily heard), hearsay (you heard it from someone else, who might have been a first-hand observer), inference (Joe must be sick, he was not feeling well and didn’t come into work today), common knowledge (everyone knows that frogs can’t fly), etc. The Ojibwe definitely have an evidential system grammatically, so when they talked in the 19th century about things from the Bible, they would say, “the alleged Jesus,” meaning, “I didn’t personally see this, and no one I know did,” etc. This hugely annoyed Baraga, who wanted them to treat the Bible as truth.” (Image: Baraga, F. A Theoretical and Practical Grammar of the Otchipwe Language. (1850). pg. 95. For example, the language is full of expressions of vagueness and uncertainty. One finds in it expressions and final suffixes that designate the degree of knowledge which the speaker has acquired from a thing or a person. For example, the Indians have heard talk of Moses, the great lawgiver, but rumor has only given them a dark idea of him. They have not seen Moses, himself, and have not yet gotten to know him better through his writings or his particular life story. Since their whole conception of “Moses” still hovers in vague outlines like a cloud, they do not even say Moses, but instead attach a certain syllable to the name in order to indicate in the idea we would express by paraphrasing, as follows: “a certain Moses” or “Moses, of whom people speak of so much.” These final suffixes are highly-varied and express different nuances and levels of acquaintance or of the celebrity of the person. With one final suffix, they can express “the famous and universally-vaunted Moses,” with another, the person of which one just speaks is merely notorious. Again, with another, they can express that they themselves still very much doubt the actual existence of this Moses, where we might say, “the often-mentioned but still very doubtful Moses.”

As long as they are still pagans, Indians never call the saints and holy persons of our religion “Moses” or “Isaiah” or “Mary” or “Christ.” These names are always spoken so that doubt or mere rumor is expressed. Of “Christ,” for example, one would say “a certain Christ,” and they always bring these expressions to Christianity, where they are supposed to believe in the existence of these personalities. I was told that it was very difficult for them to get used to this fixed and definite way of speaking.

All of these external changes are comparatively easy, of course. But while the christianization and remoulding of the inner man may look successful in these conversions, the degree of these successes is always a more-difficult question.

It is a point that is so intimately-connected with so many other great questions about the often-discussed civilizability of the Indian tribes, it could only be adequately illuminated in a great and profound work. Of course, when I share my little experiences about the Indians, I can not engage in the discussion of this great subject; but I would like to say a lot about what I personally saw and heard myself. Many of these experiences may also confirm long-standing remarks.

One sad observation that comes to mind when you travel around Lake Superior is that there are so few of missions and churches among the local Indians. It has been more than 200 years since the first Christian missionaries came to this lake. They announced to the world, in their lettres édifiantes, their beautiful, rapid, and seemingly-great successes among the Indians. 200 years after Charlemagne had defeated the barbarian Saxons and converted them “to prayer,” there were already many flourishing bishoprics, many beautiful churches, and progressive communities in Saxony, fertilized with much martyrdom and heathen blood. Here on Lake Superior, however, one hardly finds any trace of those first chapels and churches which the fathers: Jogues, Raymbaut, Ménard, Allouez, Marquette, and others built here as early as the middle of the 17th century. Their Indian communities have dissolved in the course of time. They were probably restored, but then they are, again, scattered like chaff. Little or nothing of what those men founded held firm root, and nothing has grown.

Nor does it seem that the number of Protestant missions along the lake is any different. Protestant missionary work has only begun here in recent times, but one still encounters many traces of relapses, abandoned attempts, and ruins of redeemed communities.All of the Catholic churches, congregations, and missions that we saw, and which total no more than a dozen, are a completely new work. They are all the products of the devotional efforts of the venerable and noble Father Baraga, an Austrian, who is now elevated to the position of bishop of the tidy new church and bishopric erected around Lake Superior, and who may well be called the new apostle of that lake.

Yes, everywhere the Protestant work seems far-less laid in stone than the works of the Catholics.

In Greek myth, the Dainaides were punished for killing their husbands and condemned to fill a sieve with water until full for eternity–a task impossible to complete (Painting by John William Waterhouse Wikipedia).

In Greek myth, the Dainaides were punished for killing their husbands and condemned to fill a sieve with water until full for eternity–a task impossible to complete (Painting by John William Waterhouse Wikipedia).In short, missionary work among the Indians, if followed through the course of the centuries, looks almost like the labors of the Danaides. A lot of water was poured into the sieve, but it kept dribbling out. As in a garden with weeds, they always regained the upper hand without the gardener constantly present to manage and keep watch constantly.

The few successes among the Protestants can be attributed, in part, to the fragmentation of their powers through the disunity of their jealous sects, their lack of sacrificial zeal, and the tendencies of so many missionaries to have less a sense of gaining martyrdom than of gaining a livelihood. It is also very natural that the Protestant conception of Christianity appeals to the Indian less than the Catholic one. But the reason why the Catholics, even with their their vast church, which triumphs in so many wild nations and counts corps of zealous servants, has so often failed in this Indian endeavor and has created so-little independence, must have something to do with the Indians, themselves.

The wild nature-man is in us all. He lives and works away, even in the most civilized among us. He is a piece of, or rather the basis of, our nature. Civilization is, more or less, just something artificially-constructed and planted. Not only are human civilizations somewhat prone to relapse and recklessness, every individual is as well. Culture requires a constant struggle for renewal and rebirth in all of us. We are often terrified of ourselves as occasionally whole organs and systems of our soul are stunted. We do not see how recently our nature ossified, how recently we became relaxed, or how each day we either lose our susceptibility or regain it through work and specific attention to becoming cultured. Constantly, we dust ourselves off and pull the forever-proliferating weeds. That, after we leave the schoolmaster, we do not completely degenerate, is less to our individual credit than it is a happy consequence of the fact that everything around us struggles and strives for us. This whole river of influences surrounds us and holds us in suspense like drops of water.

Here, Kohl is clearly drawing on Jean-Jacques Rousseau and other 18th-Century Enlightenment philosophers.

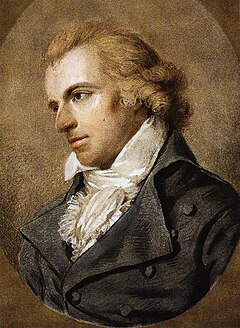

Here, Kohl is clearly drawing on Jean-Jacques Rousseau and other 18th-Century Enlightenment philosophers.  German Enlightment poet, Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) modified Rosseau’s famous quote, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” to “Man is created free, and is free, Though he be born in chains.” (Images: Wikipedia)

German Enlightment poet, Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) modified Rosseau’s famous quote, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” to “Man is created free, and is free, Though he be born in chains.” (Images: Wikipedia)How easy barbarism is for all men? Or rather, what magic enchants the wild, free, casual nature of this life? How do they easily renounce the artist’s civilization, seen in the lands of the Indians, throughout the entire period of conflict and contact?

Members of the “most civilized nation in the world,” the Frenchmen, quickly and easily become so fierce that one could scarcely distinguish them from the native savages. And it is not only the gruff French voyageurs who say that they prefer their laborious life to all the pleasures of a comfortable urban existence.

Even British officers, in the wilds of Hudson’s Bay, will tell you that they are very content in their wooden barracks. I spoke to one who seemed to talk dispassionately about his beautiful gardened island of England, which he had recently returned to on a visit. “I no longer have any desire,” he said. With a quick and eager step he rushes back to his Hudson’s Bay and will hardly ever return to Britain.

Likewise, I was told by a Protestant missionary on Lake Superior, who had recently seen Paris, Rome, and the other miraculous cities of the ancient world. He said that life there had disgusted him, and that he had now returned to Lake Superior to finish his career there. Even the Catholic missionaries are so absorbed in their work, the lake and in the Indians, that one should not even ask whether they prefer that semi-wild missionary life or a fat benefice in Lombardy. And yet, these same people later wonder why it is so hard to wean the Indian from his wild life.

“Man is free, but he would be been born in chains.” Beautiful words, they are, in the sense that our Schiller pronounced them; but in many other ways, the dear human child is born in chains and remains unfree. The civilized man is the servant of tradition and is a product of civilization. The wild forest child is a product of nature, and a slave to its overpowering elemental forces. “The Indians,” as stated by the excellent Heckewelder, “consider the whole living creation as one great society. People are indeed placed at the head of the creatures, but nevertheless exist, in intimate relation, among all the animals down to the toad. Humans are, in their opinion, in only the primus inter pares. All of living nature, in their eyes, is one great whole of which they have not dared to break away. Yes, they even go so far as to include the plants and trees, to a certain extent, in their society. Moreover they do not even exclude animals from the spirit world, their paradise, and they intend for them to go with them after death.”

(Google Books link: includes libraries it can be found in)

(Google Books link: includes libraries it can be found in) This is not just a philosophical system or theory, but a life-practice. Not only do they think of themselves as an intimate part of all living nature, but since they do think so, they are so, and because they are so, they think so. So, how can one wonder, and how can one still ask, why it is so difficult to civilize a man for whom the bear is “his brother,” the fox “his cousin,” the wolf his “forefather?” He calls the white stag his “prophet” and fears that the beaver, the rattlesnake, or the bullfrog may be angry with him if he betrays one of his religious secrets to a stranger.

Still more, they do not just see these creatures as relatives. No, they identify with them, too. “I have the soul of a buffalo in me,” they may say. But they are not merely content with that. “I am a buffalo,” or “I am a moose,” is often their decisive statement. They do not joke about this, and this is far more than a mere figure of speech, as can be shown by the thoughtful and foolishly-solemn air with which they bring these matters forward.

We have enough examples among ourselves in long-ago civilized Europe, though more-delicate and less-immediately visible, of these extremely strong bonds struck between nature and the human soul. We have the example of the half-wild gypsy tribe in mind. Cultivation conquers him only when it has completely assimilated and destroyed him. Individuals of this tribe are worked and taught by the culture and the school until the education seems to take hold. However, upon leaving and starting their employment, the overwhelming impressions of the youth, and the peculiarities of the tribes and the blood take supreme power in the fermentation process, and all these restraints are broken.

Yes, even if we want to refrain from using the example of these half-wild children of India, we need only to look around among our own people, and there is sufficient material for comparison to discover. There we find the son of the Scottish Highlands, whom no one can play the bagpipe around for fear he will forget all strict doctrines and all threats of military discipline,* and be swept away by his irresistible instinct for nature, to rush back to his beggars and his little islands. We continue with the child of the Alpine glaciers, well-educated and intelligent. He has become wealthy through speculation and industry. Suddenly, in the midst of the hustle and bustle of the city, like a tree snatched from its native stand to grow for a time before withering and dying in foreign soil, this seemingly fortunate man is seized with a terrible homesickness after hearing the ghost of a cow’s breath on the wind and he is taken with a mysterious longing pain.

(*The Highland regiments guard with bagpipe music, as we have seen. D.R.)

If something like this can happen with green wood, how surprising can it be that these people, who for millennia have grown twisted and knotty in the forest, also cannot bend into the yoke? With the above quote I gave from Heckewelder, one could consider the whole question answered and settled, C’est tout dire! one could say. If the Indian thinks of himself as part of a family that includes snakes, fishes, and fir trees, and if this belief is rooted in the whole tribe, is born in the children, and is incorrigibly in the blood, it seems incurable. Civilization seems difficult! Too difficult! –impossible?

I only say; “it seems.” For if psychological questions were all simple, if human nature were not capable of so many contrasts, then one could soon arrive at a simple “yes” or “no.” But this same man, that same “bear’s cousin” who has just quite earnestly assured you that he is descended from the wolf, or that the soul of a buffalo is in him, or that he is a moose, will soon talk to you like a philosopher. If you lead him to another field, he thinks and opines about the highest matters that you do. He rejects lies and evil with disgust. He recognizes a supreme being. He prays to him. He believes in the immortality of the soul, and in a paradise. He often practices works of unselfish hospitality, love and charity. You believe to recognize a beautiful spirit under the wild mask. You feel very friendly and connected in the soul. He is already a half Christian. He has only a few quibbles and stumbling blocks. He is like a madman, who has a “fixed idea,” but otherwise speaks like a wise man. You draw new courage and take him to your school, hoping to drive him out of this “obsession,” these “little mosquitoes and pitfalls”. To be completely safe, you take him when he is quite young–from the mother’s breast. You work on him until he grows up. But to your chagrin, even in this child of the mother’s breast, when he has come of age, those pitfalls, those wild elements and juices regain their upper hand, and destroy all your laborious work. With horror, you perceive how your adult pupil begins to suffer, to look melancholy and wistful as he goes out into the great outdoors and returns adorned with wild flowers, as he sits for hours in the garden watching the birds arrive in spring like a kitten that has been innocent up until now, but now that it has become a cat, the innate instincts show. The migratory birds pass above while the captured crane watches from the henhouse and calls to his brothers in the clouds.

One day, you are missing your foster child. He stays out into the evening and all night. Only the next day, he comes back with a concerned expression, and confesses to you that he made a journey in the forest–he could not resist–it’s so beautiful there. Of course, you become angry and admonish him severely. Your pupil is now closed-off. He loses trust and love for you, the wrathful one. He is now thinking of his complete liberation, and he obtains it on some pretext that you cannot evade–for example, by being reclaimed by his Indian father. He probably takes his right into his own hands, spreads his wings, and transformed back to bird, fish or animal– natura semper recurrit— he flies, floats or runs away from it into his native element and becomes, again, the wild hunter.

If you meet him again later, you will find him wrapped in furs, his face is painted, he is beating the drum, murmuring magic songs, worshiping the “great spirit”, and you do not know him again, since he has forgotten your hymnbook and your catechism, has completely forgotten your writing and computing tablets.

It was an English teacher who described to me a case of this kind that had come to him in his practice. I saw, myself, a few parts and pieces of this story, which are often repeated. For example, those suffering, melancholy, thoughtful, and quiet creatures are observed to have something pining in their expression (as the English often express themselves), when Indian captives grow up in the schools of Europeans, or their circumstances force them to live semi-educated among the Europeans.

I vividly recall a visit a friend and I made to an Indian woman in a big city of the American West, and the dim impression that this visit left me. This woman was estranged from the people of her earliest youth and educated in a European institution. She spoke excellent French and conversed with ease about the ordinary occurrences of life. She had been the wife of a French Canadian, who had left her a wealthy widow after his death. She lived in perfectly fortunate circumstances, and was physically well, yet she made me feel that she was a suffering person. She had something very timid in her nature. She spoke very quietly and very slowly. She did not complain, but nevertheless, everything that she said (even when we touched on completely innocuous things, as when she praised the beautiful weather we were enjoying at the time), seemed like a lament. When she talked about her half-grown daughters, the lamentation became clearer. She regretted that her children, who, as half-breeds, could never quite melt into the surrounding world and would never be fully of this world. She nearly had tears in her eyes when she talked about her children.

Those same eyes shone soft and bright as my companion mentioned her old mother, and reminded her that the summer time was already at her door, when she would see her mother out on the prairie. Her mother, an ancient Indian woman of the tribe of Ottowas*, had not decided to move with her daughter to the city, so the good daughter had bought her a piece of prairie, thirty miles from the city, and built her a log cabin. There, the mother lived by some Indian relatives, who had also found each other, and who also partly lived at the expense of the wealthy daughter, throughout the entire year in the Indian way. And in the summer, when her children’s education did not push her to the city, the daughter would go out to the prairie, exchange her pretty townhouse for the Indian bark lodge and turn into a cinderella taking care of the old mother’s domestic affairs.

(*The Ottowas live in the State of Michigan.)

Once we mentioned the mother and the prairies, there was no way around it. It remained the topic of discussion until the end of the conversation, which, as I mentioned, had felt up until that point like the reading of an elegy.

Another time, I received a similar impression during a visit to an institute for the education of Indians on Lake Superior. It was led by a Baptist preacher and his wonderful family. I just started talking to this family when a gentle song, with double-vocals, was heard in the house. “It’s Mani and Magit,” (Maria and Margarethe), I was told, “our two Indian schoolgirls singing their evening duet up in the classroom.”

“Could we not go up to them,” I begged, “and see and hear them from nearby?”

“Oh no, that will not work!” was the answer. “Our girls are as shy as deer. If they knew we were there, they would fall silent at the very least. At the most, we can stand on the stairs.”

The good old preacher and I went to the stairs and listened. The voices were exceedingly delicate and lovely, the notes round and velvety, the intonation extremely accurate, and the sound as of some soft metal. The character of the whole was of a soft, melancholy color.

As my old friend, the preacher, watched me attentively, his face became transfigured into a curious joy, as though he himself were hearing something new. So softly, softly, we crept up the stairs like the beat of a clock until, almost against our will, we stood in the classroom opposite the dark faces of the two girls.

But heavens! What had we done there!?! – Lala la la – like a torn harp string, the sound halted and the girls disappeared like a mist. They had rescued themselves by running into the next room.

“Mani! Magit! You fools! Come back. I have to introduce you to a stranger, a friend of music, who would like to hear you sing!” No answer came, no sound, just deathly silence! I think they had fainted on their sophas. The good daughters of the house went over to console them. After much convincing, they finally brought back the younger, Magit, so that we could give our apology and concern. But the older one, Mani, was unable to move. She could not recover. She disappeared, melted away like the mist, unable to regain her composure and form and did not come down to the tea afterwards, while the younger sister invited herself and later even performed a pretty solo song.

“Strange,” I thought to myself, “and these are the same bold, wild girls, the cousins of the bears, who, as long as they remain unaffected, they are not afraid to break into the camp of their enemies beside their brothers and lovers, and cut off the scalps from the dead?* Is it that they become twice ashamed and three times shy after having enjoyed the fruit of knowledge?”

(*It is not uncommon for girls to take scalps.)

“Yes,” said one of the daughters of the house, “Mani often makes me very worried. She already has that nature. Her shy manner only increases among men. In the wild she is more than normal. She has such an exaggerated romantic fondness for nature and the forest. She can sit outside for hours and look at the clouds and other things. Then, she’ll come rushing in at once, moved by an almost wild joy, to tell me she just heard the robin singing for the first time this spring, ‘I saw her red plumage shining clearly in the green foliage of the tree!’ But ‘Mani, Mani!’ I reply to her, ‘Calm yourself. It’s only a robin. What’s so special?’ ‘Oh, alas!’ she says, ‘I am so glad, so glad, to have seen the robin.’ Then she sits down at the piano and sings a melancholy song to me.”

This serious melancholy, this something pining, that the Indians adopt when transplanted from their wilderness into the so-called “garden of culture,” never comes out of them again. One notices it in their children and in their children’s children, when they are produced in the midst of whites or after marriage to whites. It stays in the blood and dies only with the blood.

Moreover, this does not only manifest itself in a suffering soul, but it also manifests itself in blood of the body itself, through peculiar diseases and ailments. I have been told many times that the habits and tendencies of civilization are incompatible with the habits and tendencies of the wild state of nature, so that the blood of the whites and the reds is hostile and far too different to amalgamate favorably. Usually, as I have been told, the first mixture still gives a tolerable product, but in the second or third mixture, degeneracy occurs, and the fruits of the tribe sicken. I mean the children become feeble and die prematurely, and in the end the whole mixed race completely loses itself by being unable to reproduce further. “It seems, then,” I replied, “that something quite different from what we see in Europe in mixtures of the related Caucasian tribes. For example, in the case of the English, the mingling of the Britons, the Normans, and the Anglo-Saxons, created such an overwhelmingly good and healthy race.”

“That’s the way it is!” they replied, “Nature, on the one hand, does not want to mix the too-closely related, as is shown in the races of many of your European countries, where through in and in breeding, the cohabitation of the cousins with cousins does not make a strong race. On the other hand, it does not want the distance to be too great. The red and the white race are set too far apart for mixing to complete. It is necessary to have certain contrasts but also certain affinities, and the latter are altogether wanting in this extremity. Therefore, very similar phenomena appears as with other extreme of close kinship: mental retardation, weakness of nerves, scrofulous diseases, and finally, lethargy and idiocy.”

I had several such or similar conversations, before I was able to observe a few cases and form my own opinion about them.

In the first stage, as it is said, everything seems to be quite beneficial, For example, with my good Canadian, Jean Picard,* he is a Canadian-born thoroughbred Frenchman. His forefathers came from Normandy. His Canadian ancestor left France as Lieutenant du Roi. He was of an old aristocratic race. Almost all of these Canadian voyageurs on Lake Superior have a head full of aristocratic ancestors, as unpretentious and miserly they must now be obliged to live. Picard’s father, mother, grandfather, grandmother, and so on, were all white, he claims, and his own snow-white complexion and all his being are a sufficient guarantor he is telling the truth.

(*It is a very common name in Canada, and I only use it here because it is convenient to have a name to use, and because his name does not matter. My man had another name.)

Despite his white blood, Picard decided to marry a dark red or brown Indian, and despite his aristocratic pretensions, he lives no better than an Indian. He has a log cabin in the interior, where he spends the winter hunting for the fur trade, and in summer, he builds a bark tent on the lake and catches fish. His wife is a genuine thoroughbred Indian; she is fat and round, not pretty, almost feisty, and looks much older than he, who is still in the prime of his manhood. But he is very pleased with her, for she is extremely patient and careful, and will spend the whole day diligently working for him in the hut, whether he is at home or not. She nurtures and educates the children with great care and indulgence, and often mends their constantly-torn clothes, sewing them for a long time, and making them so strong and good that the cloth subsequently holds far better where it has been mended than where it hasn’t been.* She cooks the fish very well for him, and from the venison he brings, she knows how to prepare a strong, nutritious soup. In addition, she has a great deal of home remedies, herbs, decoctions, and tinctures for illnesses–more than he needs, and many of them are the source of infallible relief and healing. Picard firmly believes in the Indian method of healing, and if his wife can not cure something, he turns even more confidently to an Indian doctor than to a French one.** To be sure, he does away with the hocus-pocus of the drum, the calabash, the breaking of the bones, and the necromancy of the spirits. There are Indian doctors who are sensible enough to rely on the power of their remedies and herbs. His wife is especially clever in curing the little wounds that occur daily in the rough pursuits of the husband. She knows how to treat him, excellently, and has all kinds of soothing ointments.*** In short, Mrs. Picard is a true example of an Indian housewife. And the strangest thing is that the American Indian housewives are almost all such examples. Everyone I saw said something similar to what I just described. They are all well-fed, fat, older, soft-spoken, demure, modest, industrious, busy, loyal to their husbands and patient as lambs. Even those whom I did not get to know had been described to me in this way, which is why it happens that the often impatient Frenchmen so gladly take them for their wives. They always find gentle and submissive companions in them.

(*I found out about this myself, for I once had one of these Indian women mend my skirt. Of course, she spent half a day doing this, and I, sitting next to her, smoked my whole tobacco pouch. But it was also good. The rock never tore me again in the same place, but it did elsewhere.)

(**I have seen more than one sick French-Canadian fisherman being treated by an Indian. Once I met one who had tried changing to a European doctor. He was not satisfied with him at all, so he sent him away, and returned to his Indian.)

(***How clever are the Indian women are in wound healing? I experienced it once myself. I had a sore foot. The ankle was cut, and I could not walk. It was an Indian woman, from whom I received my advice. She rubbed the wound with a fat ointment, so daintily and so cautiously, that I immediately felt relief from it. Then, out of the softest reindeer she possessed, she made me a velvet-like covering over the whole foot, especially over the wound. This quickly- improvised moccasin fit so tightly, I was able to easily slide it into my boot and walk as comfortably as if she had given me new skin).

Picard already has a half-dozen children with his wife. To me, the marriages of the French with Indian women always seemed quite blessed. The children are all cheerful, well-educated, and indeed petite! In spite of their Indian way of life, they all suggest something of the father rather than the mother. Though in their dark complexions and raven hair, they clearly show the traces of their mixed descent. The eldest Picard daughter, a girl of fourteen, has grown tall, slim and extremely proportionately built. Yes, she is gracious and moves in and out of the tent like a nimble little nymph. In her new straw cap, decorated with a red ribbon of silk, her tight flowered calico dress, and silk apron, she looks like a little Parisian middle-class girl. If you could move her directly from her hut on Lake Superior to the boulevards in Paris, so, as long as she did not betray herself of course, no discerning dandy would know that she was not born in Rue Ste. Geneviève or otherwise in the neighborhood, but that her maternal fores had been “cousins of bears.”

“Vous êtes si bonne, Mademoiselle, je vous remercie infiniment, Mademoiselle!” I said to her when, for the first time, I entered her hut and received a boiled piece of fish from her dainty hand for my breakfast. She stared at me with wide and questioning eyes, and then turned to her father to find out what I said, and whether I found something wrong with the fish. It was then that I learned that this grazie did not understand a word of French, and that she only spoke Anishinabemong (in Indian).

Of course, these “Metif ladies” have adopted a great deal of European dress. But because the mother, of course, has never been able to learn French, and because the father speaks Indian with the mother, conserving his French as much as possible for outside commerce, Indian is the language of the house, family, and children. This is what I found in all mixed French-Indian households. The little boys then start to go out and study the father’s French, and probably pick up some English as well, because once they are grown up, these Metif sons all speak French. This is their second native language. Most of the time, they also understand English, by the way. And since they have soaked up Indian with mother’s milk, they usually make the best interpreters between Europeans and Indians. In French or English alike, all the interpreters I met, including those of the American Government, were Metifs. As with the French Metis, the English or Scottish halfbreeds also mostly learn the French language and they speak it here better than most full-blood Anglo-Saxons.

I saw such dainty and pretty girls, like Picard’s daughter, quite often in the huts of the French married to Indians. They were no more like their brown, fat mothers than a duckling is to a hen. And even from their dad, they stood out clearly. The apple seemed to have fallen far away from both tribes. It was like a whole new product. For the Metif sons and young men, I did not notice it that much, but that depends more on their later lifestyle and employment. If this throws him more toward the European side, then the Frenchman starts to show more. But if they are driven back toward the Indians, the Indians seems to get the upper hand. If you watch them closely, both types always shine through.

Once, while I was on one of the elegant steamboats of Lake Huron, a young, elegant, very graceful lady, seemingly composed entirely of milk and rose-color, drew all eyes at the table upon herself and decisively won the beauty contest from all present. A friend told me he wanted to show me her birth mother, and I found an old, well-dressed, good-natured, brown, dark-clothed Indian woman. The daughter seemed to me like Preciosa, adopted by a gypsy mother. I am told that this woman has no less than 12 or 13 such lovely biological children, some of whom are more gifted than the daughter present. All are healthy, prosperous and strong. The wife is married to a very wealthy man–I no longer remember whether Scots or Frenchman.

As with Picard, I found it almost everywhere on the first level. Now I wish to show a case from the second stage where the parents both belong to a mixed race. I have known of several such cases, and if I now recall them all, it seems to me that all the children who have come out of such marriages have consistently had a decidedly-similar family resemblance whether they come from the Sioux, Ojibwe, or Iroquois.

I was visiting a Metif who will not mind if I give him the name Monsieur Favard, because he will never know in his thick woods that I have ever spoken of him anywhere. And since no one but myself knows who I mean when I say “Monsieur Favard,” there is nothing indelicate in it when, for the illumination of this subject, I speak of the domestic affairs, of this fictitious Mr. Favard.

“Favard,” though having sprung from two vivacious nationalities: the gay French and the childlike Indian, is himself neither sanguine nor childlike in character. On the contrary, I would call his bearing almost self-conscious. He seems to me like a man who has sat down between two chairs. Although he has inherited from his French father decidedly more intelligence than the Indians usually possess, and although he feels spiritually superior to the latter, he is far from entirely possessing the French mentality. A good piece of Indian indifferentism shimmers through. This expresses itself in his facial features, for they still present the bony stiffness of the Indian face, and only occasionally, like a piece of embroidery applied to a larger canvas, he shows the jovial French face more like a cruel twitch around his mouth. He speaks Canadian-French but it is mixed with some Indian expressions, and he often fell into his native tongue. He sometimes told me how much he regretted that I do not speak Indian because he explains things much better in Indian. I have been told that once, during a fairly long period of his life, he had been a hopeless and bottomless drinker, but that he had now been healed of this passion and had made a vow of renunciation. Of course, there is still much to be desired in this last relationship with the French Canadians, but it is generally said, and fairly so, that the Metifs very often degenerate into boundless indulgence, and that even if they have lived an exemplary life for a time, they could never be completely certain that the rampant Indian would not prevail in them and do away will all good intentions.

Favard’s wife, also a Metif, was probably petite and pretty as a girl. She has aged early, though, and now seemed almost more Indian than her husband. Presumably, the worries, hardships, and work of the household, which she has always done alone, have contributed to her condition. For though the family is in good circumstances, they live more or less by Indian. laws and customs, according to which, the woman gets the lion’s share of domestic labor. In her essence and nature, she has much of the something pining which, as I said, is inherent in the Indians themselves when one seeks to inculcate them with civilization. As for the rest, while the father and mother seemed physically strong and healthy, this was by no means the case with the children.

A few children (daughters) have died at a young age. Of the living three, who are almost grown, none are very healthy or strong. Two of them are girls. In general, as in this case, when I met a mixed marriage of Metifs, the female sex predominates. I would like to know if, as I suspect there is a natural law behind it. The children are all stunted, and none are very “smart” as the Americans express it. It is as if there is a hostile decomposition processes in their blood, for they all suffer from the scrofula, and have lean muscles and weak nerves. The girls are particularly shy and timid. They speak or should I say whimper, in a very squeaky, almost whiny voice. They do not talk much at all and avoided me everywhere. They only laugh at French, and are not much better at Indian. Their mental capacities are very limited. Their ideas, thoughts and manners are reminiscent of the nature of imbeciles. The poor parents, who so much want to make something of them, see with deep sorrow the sad fate of their children. The observation of this case astonished me greatly because I remember experiencing something quite similar in another mixed marriage near the Upper Mississippi.

Unfortunately, my own experiences do not go further, and as I well know, how varied nature, (despite its rules) always works and how many exceptions it makes and allows everywhere, I am far from declaring the characters and cases I described above as typical or generally-valid. It is well-known that there are many Metifs who show a superior and great spirit, and especially when they join the Indians, they become famous and imperious tribal chiefs. Conversely others, when they turn to the European side, have become very useful, honorable and even distinguished members of civil society. It may also be true that such a deterioration of the race, as I have described it, does not always appear so neatly, or perhaps even at all in the second stage.

But I am certain that all observers in the country are of the opinion that this atrophy will prove decisive over time, and that if the mixed-race wish to mingle with the mixed-race, very soon everything will come to a standstill, and end with infertility, sickness, disease, and death.

“If the half-breeds,” the American observers from different parts of the country told me, “do not return to the white or red stem, then it is over for them.” The two pure and unmixed tribes are their pillars, and their lifebloods have to straighten up and refresh.” It is well known that a very similar phenomenon has been observed in this land in cases of continued mixing between negroes and whites. Here, too, the vitality and fertility soon run out.

As I said, I give here only the contributions of a traveler; and I am well aware of how many interesting questions I leave untouched on this occasion. I have no experience of how the case will turn out if a Metif is married to an Indian or a white man, or if a Metif marries an Indian or a white woman, and whether there are particular psychological and physiological manifestations.

Selkirk’s Settlement, or the Red River Colony, was originally conceptualized in 1811 as a Scottish colony centered on what is now Manitoba, northeastern North Dakota, and northwestern Minnesota. By the time of the Red River Rebellion (1870), its population was primarily Metis of Ojibwe, Cree, Assiniboine, French and Scottish origins. Scottish Metis were pejoratively called “Bungees,” from the Ojibwe baangi (a little bit). Many of the Red River families were related to the mix-blood families of Lake Superior: Cadotte, Roy, Gurnoe, etc.

Selkirk’s Settlement, or the Red River Colony, was originally conceptualized in 1811 as a Scottish colony centered on what is now Manitoba, northeastern North Dakota, and northwestern Minnesota. By the time of the Red River Rebellion (1870), its population was primarily Metis of Ojibwe, Cree, Assiniboine, French and Scottish origins. Scottish Metis were pejoratively called “Bungees,” from the Ojibwe baangi (a little bit). Many of the Red River families were related to the mix-blood families of Lake Superior: Cadotte, Roy, Gurnoe, etc.How interesting would it be to judge the physiology of the various possible mixtures of the Red with the various European peoples? In this respect, I have only noticed how all people here agree that the marriage of a Highland Scot with an Indian gives the strongest and best Metifs. Nowhere else has this mix been stronger than in the well-known colony founded by Lord Selkirk at Pembina on the Red River. A formal mixed race of Indians and High Scots has almost formed. All the world seems to have a high regard for the substance of this mixed Scottish tribe. Everyone describes these people as vigorous, enterprising, and warlike. One told me that when a general war with the Sioux threatened: “O ho, just let the Scottish half-breeds of Pembina on them once. They are enough to keep all the Sioux in check and cut the tribe in two. They can bring 5000 men or more to arms. In the tribulations of life on the prairies where they roam and hunt buffalo as well as the Indians, they are well-accustomed to the Sioux. They have more intelligence and discipline than the Sioux, and they also have a great national hatred for them for they have each taken enough scalps off the other.”

Since, in the opinion of many, the Indians have the bony physiognomy of the Mongolian race and come from eastern Asia, and that since then, mass immigration has once-again taken place from eastern Asia. As the Chinese (who have the high-peaked bones and similar skin color as the Indian) have appeared in California, I was very eager to learn what impression these two related races make of one another. I asked about this to a gentleman from California, who had occupied himself much with the article. His answer was so strange and new to me that I cannot refrain from ending by giving it to the German reader, to whom probably seems so novel, “The Californian Indians,” my acquaintance told me, “seem to have immediately recognized the resemblance between themselves and the Eastern Asians who have appeared among them, for they generally call them: the foreign Indians.” However, they do not love them, and the Chinese have just as little sympathy for the Indians. Both are startled when they meet each other, like enemy brothers. Never does a Chinese marry an Indian, and no Indian woman ever indulges in a Chinese. The Indians harm the Chinese, they attack, they shoot them down wherever they can, which they do not do with the offspring of the other tribes of which we have in so many varieties in California. Even against the Indians of the South Sea Islands, who also come to us, they have no such antipathy. “I suppose,” my friend added, “old Indian traditions are behind it.”

In the first post in this series, I asked: “So, with most of what we know about Johann Kohl coming from Kitchi-Gami, questions remain. Do his progressive racial and religious attitudes show up in all his writings from that era? Was he truly as modern and unbiased in his thinking as we have widely been led to believe?”

So, how does he hold up?

Das Ausland billed itself as, “A weekly for scholars of the moral and intellectual lives of foreign nations.” From a cursory look at other parts of the journal (from a non-German speaker) it featured articles on Russia, Africa, East Asia, the Middle East, and the South Pacific, as well as on American Indians. Some of the articles are in support of missionary work, but that doesn’t seem to be the primary driving force behind the journal. More than anything, it feels like an 1850s version of National Geographic, designed to give information on the foreign and exotic. The word Ausland, itself would literally translate as “Outlands.” This may hold the key to understanding Kohl’s worldview.

By 1859, America still had to fight a great Civil War before it could reexamine its national character. European intellectuals, however, were already emerging from the beliefs that characterized the Romantic Period and the Second Great Awakening. Charles Darwin’s On the Origins of Species saw its first printing that year, and across the continent an emphasis on reason and science would become intellectual main-place again as it had been in 1700s.

For racists, however, that just meant that they had to use science, rather than the bible, to justify their racism.

Kohl often gets credit for being less racist than his contemporaries, but it may just be that he was just ahead of his time in his style of racism. He was not 150 years ahead of his time, but maybe he was 15 years ahead. I don’t know if Francis Galton or Herbert Spencer (who twisted Darwin’s theories into ideas of eugenics and social Darwinism) read Das Ausland as they formed the intellectual underpinnings of modern racism over the next few decades, but it’s easy to believe that they did.

Remember, it was the liberal and educated of their day who gave us Indian boarding schools, colonialism, and eugenics.

Historians are told to avoid presentism. That is, we should hold people accountable to the standards and ethics of their time and place, not ours. That is tricky for someone like Kohl, who is lauded for being an especially-modern thinker.

You don’t get to entertain ideas that, “…the blood of the whites and the reds is hostile and far too different to amalgamate favorably” and be considered a modern thinker. Kohl is gives this as second-hand information and gives disclaimers to the contrary, but he lingers on the subject at length and peppers it with other statements like, “Although he has inherited from his French father decidedly more intelligence than the Indians usually possess…” Even if Kohl was indeed less racist than his contemporaries, his work here could certainly fuel ideas of biological racism in his own time.

Kohl does not seem especially enlightened with regard to sex. Looks are clearly his way of defining women. He lusts after teenagers while deriding their mother’s physical appearance, and generally rates a woman’s competence by the quality of her domestic labor. In this, he also wasn’t forward-thinking or unusual for his times.

It is also somewhat shocking to the modern reader how Kohl uses convoluted explanations of “natural law” to explain what we in the 21st century would easily ascribe to psychological and family trauma. Mani’s shyness around men is explained as her need to be in the forest rather than by the simple fact that she had been ripped from her family to live with a strange older clergyman. Kohl makes no connection between the troubles of the “Favard” children and the depression and alcoholism of their parents. Msr. Favard has defective blood even though, as Kohl himself explains, “He seems to me like a man who has sat down between two chairs,” i.e. has been dislocated from the cultures and economies of his own ancestral communities.

So if Kohl’s worldview and understanding of the differences in people wasn’t especially modern, what is it that does separate Johann Georg Kohl from his contemporaries? Why does his work have such lasting popularity?

He was definitely a thorough and perceptive scholar. Some of his ideas are odd and outdated, but he never seems overly-wedded to them and always seeks out more information. His ego doesn’t seem so large that he would ever close himself off. More than that, however, my sense is that he was a kind, trustworthy person who took the time to listen to people. Let’s go back to line Bieder quoted from Kohl’s Travels in Canada:

“When I was in Europe, and I knew them [Indians] only from books, I must own I considered them rude, cold-blooded, rather uninteresting people, but when I had once shaken hands with them, I felt that they were ‘men and brothers,’ and had a good portion of warm blood and sound understanding, and I could feel as much sympathy for them as for any other human creatures.”

On one hand, this statement is haughty and patronizing. No modern writer would ever phrase anything this way, and I eagerly await critiques of Kohl from Native feminist authors. On the other hand, though, isn’t this all that really matters when meeting people from unfamiliar cultures: to listen to them and see their humanity? Kohl does this, and he does it over and over again in both Kitchi-Gami and Bemerkungen über die Bekehrung canadischer zum Christenthum und einige Bekehrungsgeschichten. He saw foreigners as fellow human beings: something that was all-too rare in 1855 and remains all-too rare in 2018. That is why it only took him a few months on Lake Superior to consistently able to earn people’s trust, enter their homes and hear their stories. He got some good ones. Lucky for us, he wrote them down.

Baraga, Frederic, and Albert Lacombe. A Theoretical and Practical Grammar of the Otchipwe Language: for the Use of Missionaries and Other Persons Living among the Indians. Beauchemin & Valois, 1878.

Ely, Edmund Franklin, and Theresa M. Schenck. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. Print.

Kohl, J. G. Kitchi-Gami: Wanderings round Lake Superior. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 1985. Print.

Valentine, J. Rand. “Re: J.G. Kohl on Ojibwe Suffixes and Obstacles to Christian Conversion.” Received by Leon T. Filipczak, Re: J.G. Kohl on Ojibwe Suffixes and Obstacles to Christian Conversion, 10 June 2018.

Part 1|Part 2