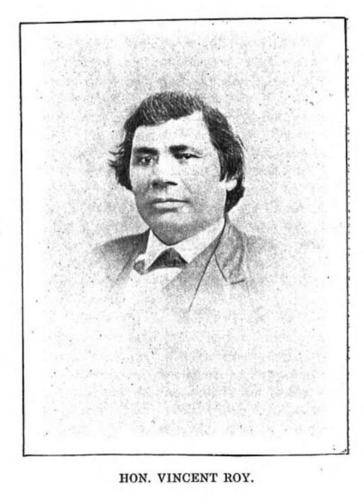

Biographical Sketch of Vincent Roy, Jr.

March 3, 2016

By Amorin Mello

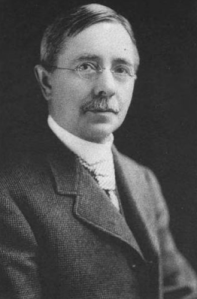

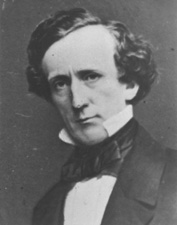

Portrait of Vincent Roy, Jr., from “Short biographical sketch of Vincent Roy,” in Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, by Chrysostom Verwyst, 1900, pages 472-476.

Miscellaneous materials related to Vincent Roy,

1861-1862, 1892, 1921

Wisconsin Historical Society

“Miscellaneous items related to Roy, a fur trader in Wisconsin of French and Chippewa Indian descent including a sketch of his early years by Reverend T. Valentine, 1896; a letter to Roy concerning the first boats to go over the Sault Ste. Marie, 1892; a letter to Valentine regarding an article on Roy; an abstract and sketch on Roy’s life; a typewritten copy of a biographical sketch from the Franciscan Herald, March 1921; and a diary by Roy describing a fur trading journey, 1860-1861, with an untitled document in the Ojibwe language (p. 19 of diary).”

Reuben Gold Thwaites was the author of “The Story of Chequamegon Bay”.

St. Agnes’ Church

205 E. Front St.

Ashland, Wis., June 27 1903

Reuben G. Thwaites

Sec. Wisc. Hist Soc. Madison Wis.

Dear Sir,

I herewith send you personal memories of Hon. Vincent Roy, lately deceased, as put together by Rev. Father Valentine O.F.M. Should your society find them of sufficient historical interest to warrant their publication, you will please correct them properly before getting them printed.

Yours very respectfully,

Fr. Chrysostom Verwyst O.F.M.

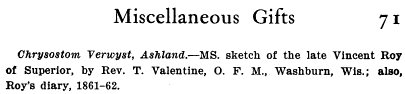

~ Proceedings of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Issue 51, 1904, page 71.

~ Biographical Sketch – Vincent Roy. ~

~ J. Apr. 2. 1896 – Superior, Wis. ~

I.

Vincent Roy was born August 29, 1825, the third child of a family of eleven children. His father Vincent Roy Sen. was a halfblood Chippewa, so or nearly so was his mother, Elisabeth Pacombe.1

Three Generations:

I. Vincent Roy

(1764-1845)

II. Vincent Roy, Sr.

(1795-1872)

III. Vincent Roy, Jr.

(1825-1896)

His grandfather was a french-canadian who located as a trader for the American Fur Company first at Cass Lake Minn, and removed in 1810 to the bank of Rainy River at its junction with Little Fork, which is now in Itasca Co. Minn.2 At this place Vincent saw at first the light of the world and there his youth passed by. He had reached his twentieth year, when his grandfather died, who had been to him and all the children an unmistakable good fortune.

‘I remember him well,’ such are Vincent’s own words when himself in his last sickness.3 ‘I remember him well, my grandfather, he was a well-meaning, God-fearing frenchman. He taught me and all of us to say our prayers and to do right. He prayed a great deal. Who knows what might have become of us, had he not been.’

The general situation of the family at the time is given by Peter Roy thus:4

“My grandfather must have had about fifty acres of land under cultivation. About the time I left the place (1839) he used to raise quite a lot of wheat, barley, potatoes and tobacco – and had quite a lot of stock, such as horses, cattle, hogs and chickens. One winter about twenty horses were lost; they strayed away and started to go back to Cass Lake, where my grandfather first commenced a farm. The horses came across a band of Indians and were all killed for food. – When I got to be old enough to see what was going on my father was trading with the Bois Forte bands of Chippewa Indians. he used to go to Mackinaw annually to make his returns and buy goods for a year’s supply.”

This trading of the Roys with the Indians was done in commission from the American Fur Company; that is they were conducting one of the many trading posts of this Company. What is peculiar is that they were evidently set up to defeat the hostile Hudson Bay Company, which had a post at Fort St. Francis, which was across the river, otherwise within sight. Yet, the Roys appear to have managed things peaceably, going at pleasure to the Fort at which they sold the farm-products that were of no use to themselves.

II.

LaPointe – School – Marriage

Grandfather Roy died and was buried on the farm in 1845. Soon after, the family broke away from the old homestead and removed to LaPointe, where a boy had been placed at school already 6 or 7 years before.5

“About the year 1838 or 1839,” says Peter Roy,6 “my father took me down to LaPointe, it then being the headquarters of the American Fur Company. He left me with my uncle Charles LaRose. (Mr. LaRose was married to his mother’s sister.) At that time my uncle was United States interpreter for Daniel P. Bushnell, U.S. Indian Agent. I went to the missionary school (presbyterian), which was under the charge of Rev. Sherman Hall. Grenville T. Sprout was the teacher.”

Officers | Where employed | Where born | Compensation

~ “War Department – Indian Agencies,” Official Register of the United States, 1839

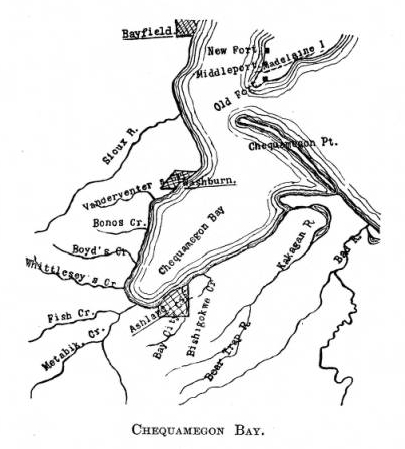

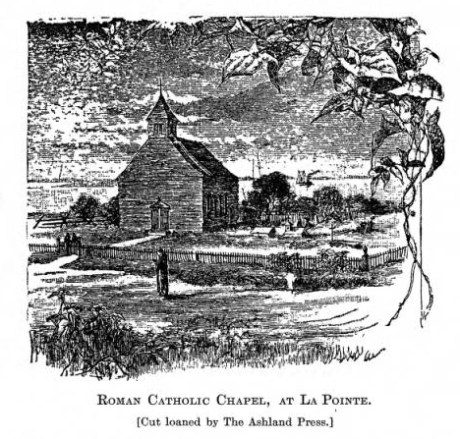

The family was acting on wise principles. Where they lived church and school were things unknown and would remain such for yet an indefinite future. The children were fast growing from under the care of their parents; yet, they were to be preserved to the faith and to civilization. It was intended to come more in touch with either. LaPointe was then a frontier-town situated on Madaline Island; opposite to what is now Bayfield Wis. Here Father Baraga had from upwards ten years attended the spiritual wants of the place.

“View of La Pointe,” circa 1842.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Our Vincent came, of course, along etc. etc. with the rest. Here for the first time in his life, he came within reach of a school which he might have attended. He was however pretty well past school age. The fact is he did not get to see the inside of a school a ten months and may be, much less, as there is an opinion he became an employ for salary in 1845, which was the year of his arrival.7 But with his energy of will made up for lack of opportunity. More than likely his grandfather taught him the first rudiments, upon which he kept on building up his store of knowledge by self-instruction.

‘At any spare moment,’ it is said,8 ‘he was sure to be at some place where he was least disturbed working at some problem or master some language lesson. He acquired a good control of the English language; his native languages – French and Ojibway – were not neglected, & he nibbled even a little at Latin, applying the knowledge he acquired of that language in translating a few church hymns into his native Ojibway. Studying turned into a habit of life with him. When later on he had a store of his own, he drew the trade of the Scandinavians of that locality just because he had picked up quite a few words of their language. Having heard a word he kept repeating it half loud to himself until he had it well fixed on his memory and the stock laid up in this manner he made use of in a jovial spirit as soon as often as an opportunity was open for it.’

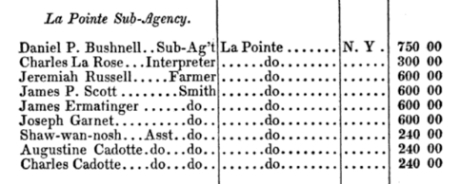

“Boardwalk leading to St. Joseph’s Catholic Church in La Pointe.” Photograph by Whitney and Zimmerman, circa 1870.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

About three years after his coming to LaPointe, Vincent chose for his life’s companion Elisabeth Cournoyer. The holy bond of matrimony between them was blessed by Reverend Otto Skolla in the LaPoint catholic church, August 13th, 1848. They did not obtain the happiness to see children born to them. Yet, they lived with each other nearly 48 years and looking back over those years there appears nothing which could not permit their marriage to be called a happy one. Their home had a good ordinary measure of home sunshine in which, in a way, children came yet to do their share and have their part.

III.

His occupation.

Vincent was employed in the interest of the fur trade with little intermission up to the forty third year of his life and thereafter until he retired from business he was engaged in keeping a general store.

“Lapointe was a quiet town in the early days and many Indians lived there. The government pay station was there and the Indians received certain monies from the government.”

“The Austrians, a fine Jewish family, established a store and maintained a good Indian trade.”

“Knowing the Indians lack of providing for the future, the Austrians always laid in extra supplies for the winter and these were doled out when necessary.”

~ Tales of Bayfield Pioneers by Eleanor Knight, 2008.

“Mr. and Mrs. Julius Austrian were among the first settlers. Splendid people they were and especially kind to the Indians. It was their custom to lay in extra supplies of flour and corn meal for they knew the Indians would be begging for them before the winter was over. On this particular occassion the winter had been extra cold and long. Food supplies were running low. The Indians were begging for food every day and it was hard to refuse them. The flour was used up and the corn meal nearly so. Still Mrs. Austrian would deal it out in small quantities. Finally they were down to the last sack, and then to the last panful. She gave the children half of this for their supper, but went to bed without tasting any herself. About midnight she was awakened by the cry of ‘Steamboat! Steamboat!’ And looking out the window she saw the lights of the North Star approaching the dock. She said that now she felt justified in going downstairs and eating the other half of the corn bread that was left.”

~ The Lake Superior Country in History and in Story by Guy M. Burnham, 1930, pg. 288.

It was but natural that Vincent turned to the occupation of his father and grandfather. There was no other it may have appeared to him to choose. He picked up what was lying in his way and did well with it. From an early age he was his father’s right hand and business manager.9 No doubt, intelligent and clever, as he was, his father could find no more efficient help, who, at the same time, was always willing and ready to do his part. Thus he grew up. By the time the family migrated south, he was conversant with the drift of the indian trade knowing all its hooks and crooks; he spoke the language of the indians and had their confidence; he was swift a foot and enduring against the tear and wear in frontier life; and there was no question but that he would continue to be useful in frontier business.

Leopold and Austrian (Jews) doing a general merchandize and fur-trading business at LaPointe were not slow in recognizing ‘their man.’ Having given employment to Peter Roy, who by this time quit going to school, they also, within the first year of his arrival at this place, employed Vincent to serve as handy-man for all kind of things, but especially, to be near when indians from the woods were coming to trade, which was no infrequent occurrence. After serving in that capacity about two years, and having married, he managed (from 1848 to 1852) a trading post for the same Leopold and Austrian;10 at first a season at Fond du Lac, Minn., then at Vermillion Lake, and finally again at Fond du Lac.11 Set up for the sole purpose to facilitate the exchange trade carried on with the indians, those trading-posts, nothing but log houses of rather limited pretensions, were nailed up for the spring and summer to be reopened in the fall. Vincent regularly returned with his wife to LaPointe. A part of the meantime was then devoted to fishing.12

A Dictionary of the Otchipwe Language, Explained in English was published by Bishop Frederic Baraga in 1853.

It was also in these years that Vincent spent a great deal of the time, which was at his disposal, with Father Frederic Baraga assisting him in getting up the books of the Ojibway language, which that zealous man has left.13

In the years which then followed Vincent passed through a variety of experience.

IV.

His first Visit to Washington, D.C. – The Treaty of LaPointe.

Read Chief Buffalo Really Did Meet The President on Chequamegon History for more context about this trip.

At the insistence of Chief Buffalo and in his company Vincent made his first trip to Washington D.C. It was in the spring of the year 1852. – Buffalo (Kechewaishke), head chief of the Lake Superior Ojibways had seen the day, when his people, according to indian estimation, was wealthy and powerful, but now he was old and his people sickly and starving poor. Vincent referring once to the incidents of that time spoke about in this way:14

“He (Buffalo) and the other old men of the tribe, his advisors, saw quite well that things could not go on much longer in the way they had done. The whites were crowding in upon them from all sides and the U.S. government said and did nothing. It appeared to these indians their land might be taken from them without they ever getting anything for it. They were scant of food and clothing and the annuities resulting from a sale of their land might keep them alive yet for a while. The sire became loud that it might be tried to push the matter at Washington admitting that they had to give up the land but insisting they be paid for it. Buffalo was willing to go but there was no one to go with him. He asked me to go with him. As I had no other business just then on hand I went along.”

Ashland, Wisconsin, is named in honor of Henry Clay’s Estate.

They went by way of the lakes. Arriving at Washington, they found the City and the capitol in a barb of morning and business suspended.15 Henry Clay, the great statesman and orator, had died (June 29) and his body was lying in state. Vincent said:

“we shook hands and spoke with the President (Fillmore) and with some of the headmen of the government. They told us that they could not do anything at the moment, but that our petition should be attended to as soon as possible. Unable to obtain any more, we looked around a few days and returned home”.

The trip had entailed a considerable drain on their private purses and the result towards the point at issue for them, the selling of the land of the indians, was not very apparent.

Henry C. Gilbert

~ Branch County Photographs

After repeated urging and an interval of over two years, during which Franklin Pierce had become President of the United States, the affairs of these Indians were at last taken up and dealt with at LaPointe by Henry C. Gilbert and David B. Herriman, commissioners on the part of the United States. A treaty was concluded, September 30th, 1854. The Lake Superior Ojibways thereby relinquished their last claims to the soil of northwest Michigan, north east Wisconsin and an adjoining part of Minnesota, and, whilst it was understood that the reserves, at L’Anse Michigan, Odanah, and Courte Oreille Wisconsin and Fond du Lac Minnesota, were set apart for them, they received in consideration of the rest the aggregate sum of about four hundred and seventy five thousand dollars, which, specified as to money and material, ran into twenty years rations.

Chief Buffalo, in consideration of services rendered, was allowed his choice of a section of land anywhere in the ceded terrain.

‘The choice he made,’ it is said,16 ‘were the heights of the city of Duluth; but never complying with the incident law formalities, it matters little that the land became the site of a city, his heirs never got the benefit of it. Of Vincent who had been also of service to the indians from the first to the last of the deal, it can only be said that he remained not just without all benefit from it.’

Julius Austrian‘s capitalization of the Mixed Blood clause from the 1854 Chippewa Treaty will be published on Chequamegon History.

A clause was inserted in the treaty (art. 2. n. 7.) 17 by which heads of families and single persons over twenty one years of age of mixed blood were each entitled to take and hold free of further charge eighty acres of the ceded lands.; – this overruled in a simple and direct way the difficulties Vincent had met with of late in trying to make good his claim to such a property. The advantage here gained was however common to others with him. For the sacrifices he made of time and money in going with Chief Buffalo to Washington he was not reimbursed, so it is believed, and it is very likely time, judging from what was the case when later on he made the same trip a second time.

V.

The small-pox.

During the two years the Lake Superior indians waited for the United States to settle their claims, important events transpired in which Vincent took part. In the fall of 1853 those indians were visited by the smallpox which took an epidemic run among them during the following winter. The first case of that disease appeared in the Roy family and it is made a circumstance somewhat interesting in the way it is given.18 Vincent and his oldest brother John B. were on some business to Madison, Wisconsin. Returning they went around by way of St. Paul Minnesota to see their brother Peter Roy who was at the time acting representative of a northern district, at the Minnesota territorial legislation which had then, as it seems, convened in extra session. On the evening previous to their departure from St. Paul, John B. paid a short visit to a family he knew from Madaline Island. In the house in which that family lived a girl had died about a year before of small-pox, but no one was sick there now at the time of the visit. If John B.’s subsequent sickness should have to be attributed to infection, it was certainly a peculiar case. The two brothers started home going by way of Taylor’s Falls, up the St. Croix river on the Wisconsin side, till Yellow Lake river, then through the woods to what is now Bayfield where they crossed over to Madaline Island. John B. began feeling sick the second day of the journey. Vincent remembered ever after the anxiety which he experienced on that homeward journey.19 It costed him every effort to keep the energies of his brother aroused. Had the same been allowed to rest as he desired he had inevitably perished in the woods. All strengths was however spent and the sick man lay helpless when the boat which carried them from the mainland touched Madaline Island. Willing hands lifted him from the boat and carried him to his house. His sickness developed into a severe case of small-pox of which he finally recovered. The indians of whom the settlement was chiefly made up did not as yet understand the character of that disease which was all the more dangerous with them for their exposed way of living. Before they were aware of it they were infected. General sickness soon prevailed. Deaths followed. Some fled in dismay from the settlement, but it may be said only to carry the angel of death to other habitations and to die after all.

Several members of the Roy family were laid up with the sickness, none of them died though.20 Vincent had been in close contact with his brother while yet on the road and had been more than any attending his brother and other members of the family in their sickness, yet he passed through the ordeal unscathed. The visitation cased with the return of spring.

VI.

Superior.

Vincent had barely emerged from the trouble just described when it was necessary for him to exert himself in another direction. A year or so previously he had taken up a claim of land at the headwaters of Lake Superior and there was improvement now on foot for that part of the country, and danger for his interests.21

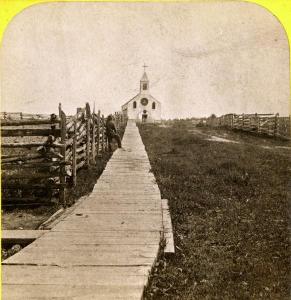

Vincent Roy Jr. storage building, circa 1933.

The following is a statement by John A. Bardon of Superior accompanying the photography, “Small storehouse building erected by the late Vincent Roy [Jr] at Old Superior. The timbers are 4′ x 8′. After the one mile dike across Superior Bay had served its purpose, it was allowed to gradually go to pieces. The timbers floating in the Bay for a while were a menace to navigation. You would find them drifting when least expected. The U.S. War Department caused the building of this dike from the end of Rice’s Point, straight across to Minnesota Point to prevent the waters of the St. Louis River being diverted from the natural entry at Superior, to the newly dug canal, across Minnesota Point in Duluth. The contention was that, if the waters of the St. Louis were diverted, the natural entrance at Superior would become shoaled from lack of the rivers scouring current. However, when the piers were extended into 18 feet of water at both the old entrance and the Duluth Canal, it was found that the currents of the river had no serious effect. The dike was never popular and was always in the way of the traffic between Superior and Duluth. Several openings were made in it to allow the passage of smaller boats. It was finally condemned by the Government Engineers as a menace to navigation. This all happened in the early 70’s. This building is now the only authentic evidence of the dike. It is owned by the Superior and Douglas County Historical Society. The writer is the man in the picture.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Read more about Vincent Roy, Jr.’s town-site at Superior City here on Chequamegon History.

The ship canal at Sault St Marie was in course of construction and it was evidently but a question of days that boats afloat on Lakes Huron and Michigan would be able to run up and unload their cargo for regions further inland somewhere on the shore at the further end of Lake Superior, at which a place, no doubt, a city would be built. The place now occupied by the city of Superior was suitable for the purposes in view but to set it in order and to own the greatest possible part of it, had become all at the same time the cherished idea of too many different elements as that developments could go on smoothly. Three independent crews were struggling to establish themselves at the lower or east end of the bay when a fourth crew approached at the upper or west end, with which Vincent, his brother Frank, and others of LaPointe had joined in.22 As this crew went directly to and began operations at the place where Vincent had his property it seems to have been guided by him, though it was in reality under the leadership of Wm. Nettleton who was backed by Hon. Henry M. Rice of St. Paul.23 Without delay the party set to work surveying the land and “improving” each claim, as soon as it was marked off, by building some kind of a log-house upon it. The hewing of timber may have attracted the attention of the other crews at the lower end about two or three miles off, as they came up about noon to see what was going on. The parties met about halfway down the bay at a place where a small creek winds its way through a rugged ravine and falls into the bay. Prospects were anything but pleasant at first at the meeting; for a time it seemed that a battle was to be fought, which however did not take place but the parceling out of ‘claims’ was for the time being suspended. This was in March or April 1854. Hereafter some transacting went on back the curtain, and before long it came out that the interests of the town-site of Superior, as far as necessary for efficient action, were united into a land company of which public and prominent view of New York, Washington, D.C. and other places east of the Mississippi river were the stockholders. Such interests as were not represented in the company were satisfied which meant for some of them that they were set aside for deficiency of right or title to a consideration. The townsite of the Superior of those days was laid out on both sides of the Nemadji river about two or three miles into the country with a base along the water edge about half way up Superior bay, so that Vincent with his property at the upper end of the bay, was pretty well out of the way of the land company, but there were an way such as thought his land a desirable thing and they contested his title in spite of his holding it already for a considerable time. An argument on hand in those days was, that persons of mixed blood were incapable of making a legal claim of land. The assertion looks more like a bugaboo invented for the purpose to get rid of persons in the way than something founded upon law and reason, yet at that time some effect was obtained with it. Vincent managed, however, to ward off all intrusion upon his property, holding it under every possible title, ‘preemption’ etc., until the treaty of LaPointe in the following September, when it was settled upon his name by title of United States scrip so called, that is by reason of the clause,as said above, entered into the second article of that treaty.

The subsequent fate of the piece of land here in question was that Vincent held it through the varying fortune of the ‘head of the lake’ for a period of about thirty six years until it had greatly risen in value, and when the west end was getting pretty much the more important complex of Superior, an English syndicate paid the sum of twenty five thousand dollars, of which was then embodied in a tract afterwards known as “Roy’s Addition”.

VII.

– On his farm – in a bivonac – on the ice.

Superior was now the place of Vincent’s home and continued to be it for the remaining time of his life. The original ‘claim’ shanty made room for a better kind of cover to which of course the circumstances of time, place, and means had still prescribed the outlines.24 Yet Vincent is credited with the talent of making a snug home with little. His own and his wife’s parents came to live with him. One day the three families being all seated around a well filled holy-day table, the sense of comfort called forth a remark of Vincent’s mother to her husband:25

“Do you remember, man,” she said, “how you made our Vincent frequently eat his meals on the ground apart from the family-table; now see the way he repays you; there is none of the rest of the children that could offer us as much and would do it in the way he does.”

It was during this time of his farming that Vincent spent his first outdoor night all alone and he never forgot it.26 It was about June. Spring had just clothed the trees with their full new foliage. Vincent was taking a run down to Hudson, Wisconsin, walking along the military wagon road which lead from Superior to St. Paul. Night was lowering when he came to Kettle river. Just above the slope he perceived a big bushy cedar tree with its dense branches like an inscrutable pyramid set off before the evening light and he was quickly resolved to have his night’s quarters underneath it. Branches and dry leaves being gathered for a bed, his frugal meal taken he rolled up in the blanket carried along for such purposes, and invited sleep to come and refresh his fatigued mortality. Little birds in the underbrush along the bank had twittered lower and lower until they slept, the frogs were bringing their concert to a close, the pines and cedars and sparse hardwood of the forest around were quiet, the night air was barely moving a twig; Vincent was just beginning to forget the world about him, when his awakening was brought on upon a sudden. An unearthly din was filling the air about him. As quick as he could extricate himself from his blanket, he jumped to his feet. If ever his hair stood up on end, it did it now; he trembled from head to foot. His first thoughts as he afterwards said, were, that a band of blood-thirsty savages had discovered his whereabouts and were on the point to dispatch him. In a few moments, everything around was again dead silence. He waited, but he heard nothing save the beating of his own heart. He had no other weapon than a muzzle-loaded pistol which he held ready for his defense. Nothing coming in upon him, he walked cautiously from under his shelter, watching everything which might reveal a danger. He observed nothing extraordinary. Facing about he viewed the tree under which he had tried to sleep. There! – from near the top of that same tree now, as if it had waited to take in the effect of its freak and to ridicule all his excitement, a screeching owl lazily took wing and disappeared in the night. The screeching of this bird with its echo in the dead of night multiplied a hundred times by an imagination yet confused from sleep had been the sole cause of disturbance. Vincent used to say that never in his life he had been so upset as on this night and though all had cleared up as a false alarm, he had had but little sleep when at daybreak he resumed his journey.

Another adventure Vincent had in one of these years on the ice of Lake Superior.27 All the family young and old had been on Bass Island near Bayfield for the purpose of making maple-sugar. That meant, they had been some three weeks in March-April at work gathering day and night the sap tapped from maple-trees and boiling down to a mass which they stored in birch bark boxed of fifty to hundred and fifty pounds each. At the end of the season Vincent got his horse and sleigh and put aboard the product of his work, himself, his wife and two young persons, relatives of his wife, followed; they were going home to Superior on the ice of the lake along the shore. When they came however towards Siskowit bay, instead of following the circuit of the shore, they made directly for Bark Point, which they saw standing out before them. This brought them out on a pretty big field of ice and the ice was not to be trusted so late in spring as it was now. Being almost coming in upon the point they all at once noticed the ice to be moving from shore – a split was just crossing through ahead of them. No time was to be lost. With a providential presence of mind, Vincent whipped his horse, which seemed to understand the peril of the situation; with all the speed it could gather up in a few paces it jumped across the gap. The sleigh shooting over the open water struck the further ice edge with a thump yet without harm – they were safe.

By pressure of other ice wedging in at a distance or from the hold which wind and wave get upon it, a considerable area of ice may, sometimes in spring, break loose with a report as that of a cannon and glide apart some ten feet right out upon the start. That it happened different this time and that our travelers did not drift out into the lake with a cake of ice however large yet, any thawing away or breaking up under them, was their very good fortune.

VIII.

– Superior’s short-lived prosperity – V. at his old profession – a memorable tour.

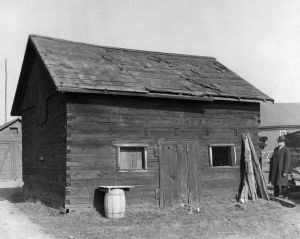

Built circa 1857, photographed circa 1930.

“The trading post was owned by Vincent Roy [Jr]. The Roy family was prominent in the early history of the Superior area.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Vincent was too near Superior as not to feel the pulsation of her life and to enter into the joys and sorrows of already her infant days.28 The place had fast donned the appearance of a city; streets were graded, lines of buildings were standing, trades were at work. Indeed, a printing office was putting out at convenient intervals printed matter for the benefit of the commonwealth at home and abroad; then was a transfer of real-estate going on averaging some thousand dollars a week, town lots selling at two to three hundred dollars each; and several stores of general merchandise were doing business.

The scarcity of provision the first winter was but an incident, the last boat which was to complete the supply being lost in a gale. It did not come to severe suffering and great was the joy, when a boat turned up in spring especially early.

In short, the general outlook had great hopes on the wing for the place, but its misgivings came. Its life blood ceased to flow in the financial crisis of September 1857, as the capital which had pushed it was no more forthcoming. It was a regular nor’easter that blew down the young plant, not killing it outright but stunting its growth for many, many years to come. The place settled down to a mere village of some hundred inhabitants, doing duty of course as county seat but that was not saying much as the whites stood in that part of the country all the way to pretty well up in the eighties.

~ The Superior Chronicle, July 7th, 1860.

About 1856 Vincent embarked again in the profession of his youth, the fur trade. Alexander Paul who did business in “The Superior Outfit” on Second Street, engaged his services. After a few years the business passed into the hands of Peter E. Bradshaw; which however did not interfere with Vincent. He was required to give all his attention to fur and peltry; first to getting them in, then to sorting them and tending to them until they were set off in the east. His employers had trading posts along the north shore at Grand Marais and Grant Portage, about the border line at the Lakes Basswood, Vermillion and Rainy, then at Lower Red Lake, at Mud Lake east of Leech Lake and at Cross Lake about thirty miles north of Crow Wing Minnesota. A tour of inspection of these posts was necessary on the average in the fall to see what was needed to be sent out, and in the spring to get home the peltries which had been obtained.29 One tour in which Vincent, Mr. P Bradshaw, Francis Blair, and one or two others, made up the party, was regarded especially memorable. It was undertaken early in spring, perhaps in February since the calculation was to find brook and lake yet passable on the ice. The party set out with the usual train of three dogs harnessed to a toboggan which carried as long as the dogs did not give out, the most necessary luggage; to wit, a blanket for each the men to roll up in at night and the supply of food consisting in a packet of cornmeal with a proportionate amount of tallow for the dogs and bacon for the men to add, the Canadian snowshoes being carried in hand any way as long and wherever they would be but an incumbrance to the feet. Their way led them along the wagon road to Kettle river, then across the country passing Mille lac Lake to Crow Wing, then northward to touch their posts of Cross and Mud Lake, moving nearly always on the ice in that region of lakes in which the Mississippi has its beginning. After leaving the Mud Lake post a swamp of more than a day in crossing was to be traversed to reach the Red Lake post. They were taking the usual trail but this time they were meeting more than usual inconvenience. They had been having a few days soft weather and here where the water would not run off they found themselves walking knee-deep in the slush, to increase their annoyance it set in drizzling. Still they trudged along till about mid-afternoon when they halted. The heavens scowling down in a gray threatening way, all around snow, from which looked forth, an occasional tuft of swamp grass, otherwise shrubby browse with only at places dwarfed pine and tamarack, were sticks of an arm’s thickness and but thinly scattered, they were in dread of the night and what it might bring them in such dismal surrounding. They were to have a fire and to make sure of it, they now began to gather sticks at a place when they were to be had, until they had a heap which they thought would enable them to keep up a fire till morning. The next thing and not an easy one was to build a fire. They could not proceed on their usual plan of scraping away the snow and set it up around as a fortification against the cold air, it would have been opening here a pit of clear water. So they began throwing down layers of sticks across each other until the pile stood in pierform above water and snow and furnished a fire-place. Around the fire they built a platform of browse-wood and grass for themselves to lie upon. But the fire would not burn well and the men lay too much exposed. Luckily the heavens remained clouded, which kept up the temperature. A severe cold night easily have had serious results in those circumstances. The party passed a very miserable night, but it took an end, and no one carried any immediate harm from it.

Next morning, the party pushed forward on its way and without further adventure reached the Red Lake post. Thence they worked their way upwards to the Lake of the Woods, then down the Rainy Lake River and along Rainy Lake, up Crane Lake, to Pelican Lake, and finally across Vermillion Lake to the Vermillion post, about the spot where Tower, Minn. now stands. Thence back to Superior, following the water courses, chiefly the St. Louis river. The distance traveled, if it is taken in a somewhat straight line, is from five to six hundred miles, but for the party it must have been more judging from the meandering way it went from lake to lake and along the course of streams. That tour Messrs. Bradshaw required for their business, twice a year; once in the winter, to gather in the crops of furs of the year and again in the fall to furnish the posts with provision and stock in trade and the managing there lay chiefly upon Mr. Roy. As to the hardships on these tours, dint of habit went far to help them endure them. Thus Mr. Bradshaw remarked yet in 1897 – he did not remember that he or any of his employees out on a trip, in the winter, in the open air, day and night, ever they had to be careful or they get a cold then.

“As any who have tried snowshoes will know, there is a trick to using them. The novice will spread his legs to keep the snowshoes from scraping each other, but this awkward position, like attempting too great a distance before conditioning oneself to the strain, will cause lameness. Such invalids, the old voyageur type would say, suffer from ‘Mal de raquette.’“

~ Forest & Outdoors, Volume 42, by the Canadian Forestry Assocation, 1946, page 380.

Not infrequently a man’s ingenuity came into action and helped to overcome a difficulty. An instance in case happened on the above or a similar tour. Somewhere back of Fond du Lac, Minn, notwithstanding the fact that they were approaching home, one of the men declared himself incapable of traveling any longer, being afflicted most severely with what the “courreurs du bois” called “mal de la raquette.” This was a trouble consequent to long walks on snow shoes. The weight and continual friction of the snow-shoe on the forefoot would wear this so much that blood oozed from it and cramps in foot and leg set in. In this unpleasant predicament, the man was undismayed, he advised his companions to proceed and leave him to his fate, as he would still find means to take care of himself. So he was left. After about a week some anxiety was felt about the man and a search-party set out to hunt him up. Arriving at his whereabouts, they found their man in somewhat comfortable circumstances, he had built for himself a hut of the boughs of trees and dry grass and have lived on rabbits which he managed to get without a gun. So far from being in need of assistance, he was now in a condition to bestow such for it being about noon and a rabbit on the fire being about ready to be served he invited his would-be-rescuers to dinner and after he had regaled them in the best manner circumstances permitted, he returned home with them all in good spirits.

The following incidents shows how Mr. Roy met an exigency. Once at night-fall he and the men had pitched for a night’s stay and made preparations for supper. No game or fish was at hand. A brook flowed near by but there was nothing in the possession of the crew to catch a fish with. But Roy was bent upon making the anyway scant fare more savory with a supply of fish, if it could be. Whilst the rest made a fire, he absented himself and in a very short time he returned with a couple of fish fresh from the water and sufficiently large to furnish a dish for all. He had managed to get them out from the brook with no other contrivance than the forked twig of a tree.

The following trip of Mr. Roy is remembered for the humorous incidents to which it gave occasion. One summer day probably in August and in the sixties, a tourist party turned up at Superior. It consisted of two gentlemen with wives and daughters, some six or seven persons. They were from the east, probably New York and it was fairly understood that it was the ambition of the ladies to pose as heroines, that had made a tour through the wild west and had seen the wild indian in his own country. The Bradshaws being under some obligation to these strangers detailed Roy and a few oarsmen to take them by boat along the north shore to Fort William, where they could take passage on a steamer for the continuation of their journey.

Now the story goes that Roy sent word ahead to some family at Grand Marais, Minn. or thereabouts that his crew would make a stop at their house. The unusual news, however, spread and long before Roy’s boat came in sight, not only the family, which was to furnish hospitality, was getting ready, but also their friends; men, women and children, in quite a number, had come gathering in from the woods, each ready for something, if no more, at least to show their wild indian faces.

Maple sugar in a birch bark container.

~ Minnesota Historical Society

When Roy and the gentlemen and ladies in his custody had arrived and were seated at table, the women and girls busied themselves in some way or another in order to make sure not to miss seeing, what was going on, above all how the strange ladies would behave at table. The Indian woman, who had set the table, had put salt on it – simply enough it is said for the boiled eggs served; – but what was peculiar, was that the salt was not put in salt-dishes, but in a coffee cup or bowl. If sugar was on the table, it was maple-sugar, which any Indian of the country could distinguish from salt, but the ladies at the table were not so versed in the customs of the country through which they were travelling, they mistaking the salt for sugar, reached for it and put a tea-spoonful of it into their tea or coffee. A ripple of surprise ran over the numerous spectators, the features of the older ones relaxing somewhat from their habitual rigor and a half-suppressed titter of the younger being heard – possibly in their judgement, the strange ladies of the city in the east were the less civilized there. In fact, the occurrence was never forgotten by those who witnessed it.

Proceeding on their journey, one night Roy and those in his custody had not been able to take their night’s rest at a human habitation and had chanced to pitch their tents on a high embankment of the lake. During the night the wind arose and blew a gale from the lake, so strong that the pegs of the tents, in which the ladies were lodged, pulled up and the canvass blew away. When the ladies were thus on a sudden aroused from sleep and without a tent out in the storm they screamed for their life for Roy to come to their aid. The men helped along with Roy to set up the tent again. Roy often afterwards amusingly referred to this that the ladies had not screamed for their husbands or fathers, but for Roy. The ladies gave later on their reasons for acting thus. Not knowing the real cause of what was transpiring, they in their freight thought the wild Indians were now indeed upon them that they were on the point of being carried off into the woods. In such a peril they of course thought of Roy as the only one who could rescue them. After the excitement things were soon explained and set aright and the ladies with their husbands and fathers arrived safely at Fort William and took passage in due season on an east-bound steamer.

A Friend of Roy.

Sources of Inform:tion

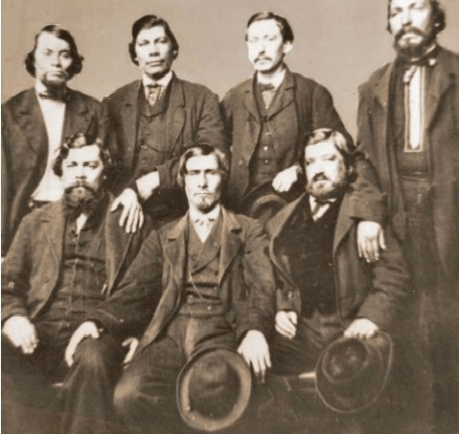

“Top: Frank Roy, Vincent Roy, E. Roussin, Old Frank D.o., Bottom: Peter Roy, Jos. Gourneau (Gurnoe), D. Geo. Morrison.” The photo is labelled Chippewa Treaty in Washington 1845 by the St. Louis Hist. Lib and Douglas County Museum, but if it is in fact in Washington, it was probably the Bois Forte Treaty of 1866, where these men acted as conductors and interpreters (Digitized by Mary E. Carlson for The Sawmill Community at Roy’s Point).

1 His journal and folks.

2 Pet. Roy’s sketch.

3 Mr. Roy to V.

4 P. R.’s sketch

5 Mr. Geo. Morrison says, the place was in those days always called Madelaine Island.

~ The Superior Chronicle, July 7, 1860.

6 P. Roy’s sketch.

7 His wife.

8 His folks.

9 Cournoyer.

10 Mrs. Roy.

11 See foot-note.

12 Mrs. Roy.

13 Fr. Eustachius said smthng to this effect.

14 Mr. Roy to V.

15 Cournoyer or Mr. Roy to V.

16 Cournoyer.

18 by Geo. Morrison & others.

19 Mr. Roy to V.

20 The family.

21 Mr. Roy to V.

22 Mr. Roy to V.

23 History of Superior as to the substce.

Vincent Cournoyer was Vincent Roy Jr’s brother-in-law. The Roy brothers, Cournoyer, Morrison, and La Fave were all Mixed-Blood members of the Lake Superior Chippewa, and elected officials in Douglas County, Wisconsin.

24 The family.

25 Cournoyer.

26 Mr Roy to V. – His family also.

27 Mr. Roy to V. – His family also.

28 History aS subst.e

29 Mr. J. Bradshaw and J. La Fave.

Father Valentine wishes his name to be suppressed in this communication and hence signs himself as above: “A Friend of Roy.”

Fr. Chrysostom Verwyst O.F.M.

Reverend Chrysostome Verwyst, circa 1918. ~ Wisconsin Historical Society

1848 La Pointe Annuity Payments

March 2, 2016

By Amorin Mello

American Fur Company Papers: “Map of La Pointe”

drawn by Lyman Marcus Warren, 1834.

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

Hercules Louis Dousman

“In 1827, the American Fur Company (AFC) achieved a monopoly on the fur trade in what is now Minnesota. The Company suddenly increased its prices by 300 percent; American Indians, returning from the hunt with expectations of trading for their yearly supplies, found themselves cast into a debt cycle that would increase in the decades ahead. American Indians would receive virtually unlimited credit as long as they maintained the most precious collateral: land.

As game was overhunted and demands for furs changed, the system collapsed under a burden of debt. In 1834, AFC departments were sold to partners who included the Chouteaus, Henry Sibley, and Hercules Dousman. The business strategy of the reorganized companies changed from fur trading to treaty making. In 1837, economically stressed Dakota and Ojibwe people began selling land in what became Minnesota. Fur traders, through their political connections, were able to divert government payments for American Indian land into their own pockets. In effect, land cession treaties became a vast government bailout of fur trade corporations.”

~ Relations: Dakota & Ojibwe Treaties

Henry Hastings Sibley Papers 1826-1848

Henry Hastings Sibley

~ Minnesota Historical Society

Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center

History Center & Archives

“Papers of Minnesota’s first governor during his years as a fur trader, consisting primarily of correspondence among the various American Fur Company agents located in the Wisconsin Territory. Correspondence concerns internal company business; business with Hudson Bay Fur Company; company agreements with the Dakota Indians; company interest in United States government treaties with the Dakota, Ojibwa, and Winnebago Indians; attempts by the company to prevent war between the Dakota and the Sauk and Fox Indians; relations with missionaries to the Indians of the region; and company disputes with Indian agents Henry R. Schoolcraft and Lawrence Taliaferro.

Correspondents prominent in the early history of Minnesota and Wisconsin include William Aitken, Frederick Ayer, Alexis Bailly, Bernard Brisbois, Ramsay Crooks, Henry Dodge, James Doty, Hercules Dousman, Jean Faribault, Alexander Faribault, Joseph Nicollet, Henry Rice, Joseph Rolette, Henry Schoolcraft, Lawrence Taliaferro, and Lyman Warren.”

New York April 17, 1848

To Geo Ebninger Esq.

Assignee Am. Fur Co.

Dear Sir,

Pierre Chouteau, Jr.; son of French Creole fur trader, merchant, politician, and slaveholder Jean-Pierre Chouteau.

~ Wikipedia.org

We hasten to reply to you, of this date offering to sell “The American Fur Co Establishments at Lapointe” all the Northern Outfit Posts: – “The whole for twenty five hundred dollars ($2500)” provided we will take the goods remaining on hand there after this spring’s trade at New York cash for sound Merchantable goods everything else as its fair actual value & say that we regret you waited until the moment our senior was leaving for the west before making the above proposition & also some days after the departure of Mr. Rice. It is probable, if your letter had been received during his stay here, that we would have accepted it or made other propositions which would have been agreeable. We thought if you were desirous of selling the Establishments & goods that you would have apprised us earlier of your intentions & given us time to consult or reflect upon it. And we expect, and hope that you will give us time to communicate your proposition to the persons interested with us in Upper Mississippi & particularly with Mr. Rice who alone has visited the posts & has a correct idea of their value.

Believing that the delay we ask will not or cannot be prejudicial to your interests we will wait your answer.

Very respectfully

yr obd svt

P Chouteau Junr

New York 28th June, 1848

Mister P Chouteau Jr & Co

New York

Gentlemen,

Agreeably to what I had the pleasure to address you on the 14th April last, copy of which letter is annex I will sell you the late American Fur Company’s Establishment at La Pointe & as the terms and conditions as before named, delivery to be made to you or your agent on a date to be hereafter agreed upon between the First day of September and Fifteenth day of October next and ending Payments for the same to be made in New York to me in October or November next.

Please let me have your written reply to this proposition.

I am gentlemen bestly

Your Obedt Servt

George Ebninger

Assignee to P Chouteau Jr, St Louis

New York 30th June, 1848

To George Ebninger Esq.

Assignee Am Fur Co.Dear Sir,

View of La Pointe, circa 1843.

“American Fur Company with both Mission churches. Sketch purportedly by a Native American youth. Probably an overpainted photographic copy enlargement. Paper on a canvas stretcher.”

~ Wisconsin Historical Society

In reply to yours of 28th inst (with copy annexed of similar letters under date 14th April last) we have to say that under advises lately received from our Saint Louis house we accept in general terms your proposition for the sale of the American Fur Co’s trading Establishment at Lapointe and interior for the sum offered, of Twenty Five Hundred dollars. It may be well enough to observe how ever that we consider the sale as dating only from the time of delivery to our authorized agents. Until then received we shall consider the posts as the property of Late American Fur Co and to be as their risk and any destruction of property between now and the time you may fix for delivery to be their loss and not ours.

The terms of payments proposed by you are entirely acceptable. But we think it might be better to make it more definite and accordingly suggest that our agents who received the property draw upon us as forty days & nights for the amount. Hoping that these slights exchanged may meet your sanctions and that you will name an early day for the delivery of posts & we remain very truly,

Your Obedt Servt

P. Chouteau Jr & Co

New York 5th July 1848

P Chouteau Jr Esq

Saint LouisDear Sir

“Ramsey Crooks (also spelled Ramsay) was born in Scotland in 1787. He immigrated to Canada in 1803 where he worked as a fur trader and explorer around the Great Lakes. He began working for the American Fur Company, which was started by John Jacob Astor, America’s first multi-millionaire, and made an expedition to the Oregon coast from 1809-1813 for the company. By doing so he also became a partner in the Pacific Fur Company. In 1834 he became acting president of the American Fur Company following Astor’s retirement to New York. A great lakes sailing vessel the Ramsey Crooks was constructed in 1836 by the American Fur Co. A nearly identical sister ship was built in the same year and was called the Astor. Both ships were sold by the dissolving fur company in 1850. Ramsay Crooks passed away in 1859, but had made a name for himself in the fur trade not only in Milwaukee and the Great Lakes, but all the way to the Pacific Ocean.” ~ Milwaukee County Historical Society

On the 28th June I sold to your house the Establishments of the late American Fur Company at Lapointe agreeably to the letter I had written to you on the 14th April. Cash delivery to be made at some period to be agreed upon hereafter between the first day of September and fifteenth day of October next. I hope that it may be in my power to get to Lapointe and attend to the delivery to your agents but if not we must select some other to act for me, Mr. Crooks and myself are not on good terms in [cou-bethee?] ease as he has been opposed to the sale being made by from the bush. I have lately heard that Mr. Crooks has written the Establishment & at Lapointe (Mr. [Ludgem?] of Detroit told me so while in the city lately) and he must have written to him shortly after the offer was made to you here, and it remains to be seen what authority he can have to dish use of the property which has been assigned to me and over which I have acted as assignee for nearly the last six years. Mr. Crooks acts of leaving here shortly for the Northern Posts. Before then I shall know what he proposes to do to annul the sale I have (under the authority vested in me as assignee) made to you, and which has been made agreeably to his only Suggestions on the 14th day of April last, and the only objection he can make to the Sale is that you did not as once accepts of his but required only a reasonable time to reply to which I was willing to grant and would again give under such circumstances you being there on the eve of leaving here, but it was clear enough that Mr. Crooks never wished that you should have the Northern Outfit Establishment, but that his friend Borrup should. I shall however do all that I can to oppose his injust views on that score.

I am In Most Truly

Your Obedt Servt

George Ebninger

Aspring politician and future Senator Henry Mower Rice represented the Chippewas at the 1847 Treaty of Fond du Lac, and appears frequently here on Chequamegon History.

~ United States Senate Historical Office

St. Louis July 14, 1848

Mr.s Sibley & Rice

St. PetersDr. Sirs

We had this pleasure of the 7th inst by [Shamus Highland Many?] enclosing Invoice & Bill of Landing of C.O. English goods which we hope you will have received in good order and due time – The same day and as the time the boat was pushing off we addressed you a few lines in haste, advising you of the purchase made by our House in New York, of the posts at Lapointe. We have just received several documents in relation to that purchase of which you will find copies herewithin.

You will perceive from their contents how Mr. Crooks has acted in the matter, and that it has become urgent for us to take such steps as will answer the possession of the said posts. How we will be able to succeed, Doctr. Borrup being now in possession & having apparently purchased from Mr. Crooks, is a matter of doubt and can only be ascertained at Lapointe. We have purchased Bona Fide from Mr. G. Ebninger, the only person authorized to make sale, as the assigner of the late American F. Co. Mr. Borrup we are afraid, will (as you can see by Mr. Sanford’s letter) refuses to give possession, and in that case, in a country where there is no way of enforcing law, we may not be able to obtain possession before next year. Now, would it be desirable or advantageous to make the purchase and not get possession before that time? We think not.

Oil painting of Doctor Charles William Wulff Borup from the Minnesota Historical Society:

“Borup and Oakes were headmen for the [American Fur Company]. All voyageurs, ‘runners,’ as they were called, were employed by said company. They would leave La Pointe about the beginning of September, stay away all fall and winter among the Indians in their respective districts, collect furs, and return about the beginning of June. They would take along blankets, clothes, guns, etc., to trade with the Indians for their furs. They took along very little provisions, as they depended mostly on hunting, fishing, wild reice, and trade with the Indians for their support. There were several depots for depositing goods and collecting furs, for instance at Fond du Lac (Minnesota,) Sandy Lake, Courtes Oreilles, Lac du Flambeau Mouth of Yellow River, etc.”

~ Proceedings of the [Wisconsin Historical] Society at its Sixty-fourth Annual Meeting, 1917, pages 177-9

We are writing this day to our home in New York and to Mr. G. Ebninger that he must proceed immediately to Lapointe so as to be here from the 1st to the 15th September, and claim himself & in person the delivery of the posts. Any agent would not probably succeed, or objections would no doubt be made by Doctr. Borrup which said agent could not face or answer. You will therefore do the necessity of either of you going to Lapointe and meet them with Mr. Ebninger on the time appointed above.

Very truly yours,

P. Chouteau Jr & Co

It was only on the 10th inst that we were handed your forms of 25 june enclosing packing ‘℅’ of the U.S. postal M.R. #01037 for ℅ St Louis ℅ Chippewa outfit. Capt. Ludwick ought to be more particular with papers confided to his care.

Bernard Walter Brisbois was an agent for the American Fur Company.

Duplicates of this letter and documents enclosed, sent to the care of Mr. Brisbois of Prairie du Chien, by mail

You will notice by copy of telegraphic dispatch of the 10th that the Chippewa annuity will be paid at Lake Superior as heretofore.

[Illegible]

The New York Times

September 29, 1851

“Indian Moneys”

There is no greater abuse in the governmental policy of the United States, than the past and present system of Indian payments; and the Indians would be benefited if the money thus appropriated were cast into the Lakes, rather than made the cause of such much distress and swindling as it is.

The author of this article is not identified.

In the August of 1848 we were present at a payment at La Pointe, and we have no hesitation in saying that every dollar paid to the Indians there was a disadvantage rather than a benefit to them.

The payment was fixed for August, and Indians from West of the Mississippi were called together at La Pointe to receive it. They gathered at the appointed time, and the payment was not made for three weeks after the time specified.

The money collected at the Saut Ste. Marie Land Office, the most convenient point, had been transported, as per Government order, to Chicago, and the Paymaster received drafts on that point where he was compelled to go for the specie, and the payment was thus delayed.

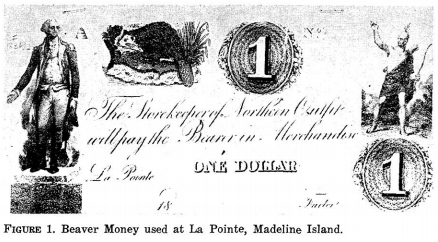

La Pointe Beaver Money of the American Fur Company’s Northern Outfit from “The Beaver in Early Wisconsin” by A. W. Schorger, Wisconsin Academy of Science, Arts, & Letters, Volume 54, page 159.

Meantime, the Indians gathered at La Pointe were without the necessaries of life, and the agents of the North American Fur Company, and a few old traders who were posted in the business, supplied them with provisions at exorbitant rates, and forced them to buy with every ounce of pork or flour which they needed, an equal amount of dry-goods and gewgaws, which had no value for them. These sales were made on credit, to be settled at the pay-table. At the payment, some $30,000 in cash, and a stipulated quantity of blankets, guns, powder, tin pails, calicoes, ribbons, &c., were distributed; and this American Fur Company, and the favored traders, raked from the Paymaster’s table as it was counted out to the bands, over $12,000 for provisions furnished to, and trash forced upon the Indians, while they were delayed after being summoned to the payment.

Some $14,000 more was spent among forty traders and the remaining $4,000 the Indians carried home; about one dollar each.

Their blankets, about the only valuable thing they received in the way of dry goods, were on the night after payment, mostly transferred to a mercenary set of speculators, at a cost of a pint of whiskey each, and came down to the Saut as private property on the same propeller that took them up as government gratuity.

Such was the result of a payment for which thousands of Indians traversed many miles of forest, wasted six weeks’ time, and lost the crop of wild rice upon which they depended for their winter’s subsistence.

If a white man with a white soul, writes the history of the Indians of the West, the American government will gain little credit from his record of Indian payments.

For more context about these American Fur Company partners and their affairs following the 1848 La Pointe annuity payments, please read pages 133-136 of Last Days of the Upper Mississippi Fur Trade by Rhonda R. Gilman, Minnesota History, Winter 1970.

But the swindle of 1848 was not gross enough to suit certain grasping parties. La Pointe was too easy of access. So many traders sought a market for their goods there, that the old monopolists could not obtain a thousand per cent on the goods they sold; and even in 1848, it was whispered that they were using all their influence to have the future payments made at some point so far West that competition would not force them to be content with moderate profits.

For more context about the Lake Superior Chippewa following the 1848 La Pointe annuity payments, please read our The Sandy Lake Tragedy and Ojibwe Removal series here on Chequamegon History.

To effect this it was necessary to remove the Chippewas further West, and by some influence, not, perhaps, distinctly marked, but yet more than suspected, this order of removal was secured.

It was uncalled for, useless, and abominable; and we are glad, for the sake of humanity and justice, that the Administration have resolved that for the present the edict shall not be enforced. We trust it may never be.